90-odd years after he first tromped onto the stage of Thimble Theatre, Popeye’s in a strange position. He’s so entrenched in American pop culture he’s unlikely to ever be forgotten, but he’s remembered for the wrong reasons. The same way Popeye took over Thimble Theater and buried its original stars, Castor Oyl and Ham Gravy, the animated Popeye has buried its newsprint predecessor.

And that’s a shame. The classic Fleischer cartoons are often very good, but the original comics by E.C. Segar, who punnily signed his name with a cigar butt, are something else altogether. Instead of just episode after slapstick episode of Popeye beating up Bluto (who Segar only used once), Segar’s Popeye went everywhere and did everything. Segar would improvise epic stories that could last for months and go anywhere or nowhere. He could create lighthearted adventure or heavy, shadowy atmosphere that Fleischer somehow never matched despite proving they were more than capable of it in their nightmarish Betty Boop cartoons. And most incredible of all, he gave this stock comic characters real depth and even heartache.

The difference between the two Popeyes has been exaggerated. Yes, comics Popye does eat spinach. It’s just not the deus ex machina the cartoons repeated beat for beat over and over again whenever it seems like their hero’s down and out. Comics Popeye eats it all the time, which means he’s always that tough.

And I can’t be too down on the cartoons — without them, Popeye would have gone the way of Barney Google or The Toonerville Trolley. Thanks to their ubiquity, Segar’ comics are still floating around for anyone who wants to seek them out, and they’re well worth the effort. Popeye is what it is, and what it is is pretty fucking great.

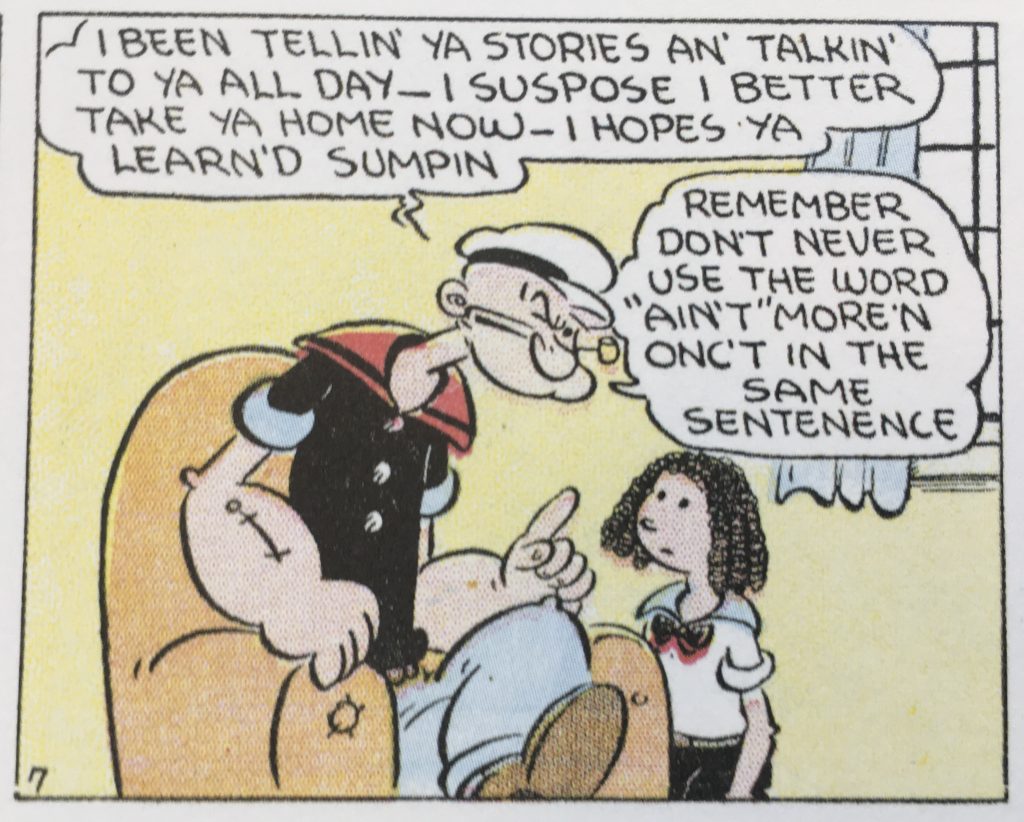

Popeye emerges as a much fuller character in the comics. Segar created the bridge between the classic American tall tales and the modern superhero. Like the tall-tale heroes, Popeye is a working man whose incredible strength is almost always played for laughs. But putting that exaggeration in the comics form and the action-adventure format got something stirring in the American animation. Superman’s creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster say they were inspired by the thought that if they played Popeye straight, they’d have “the most sensational action hero.” But Popeye’s more complex than superheroes would be for decades after him. He’s got a mean streak a mile wide. But his increasing popularity forced Segar to soften him in intriguing ways to make him an acceptable role model, undercutting his violence with an unbending sense of justice and a love for the underdog — “widows and orphinks,” as he put it, but especially children.

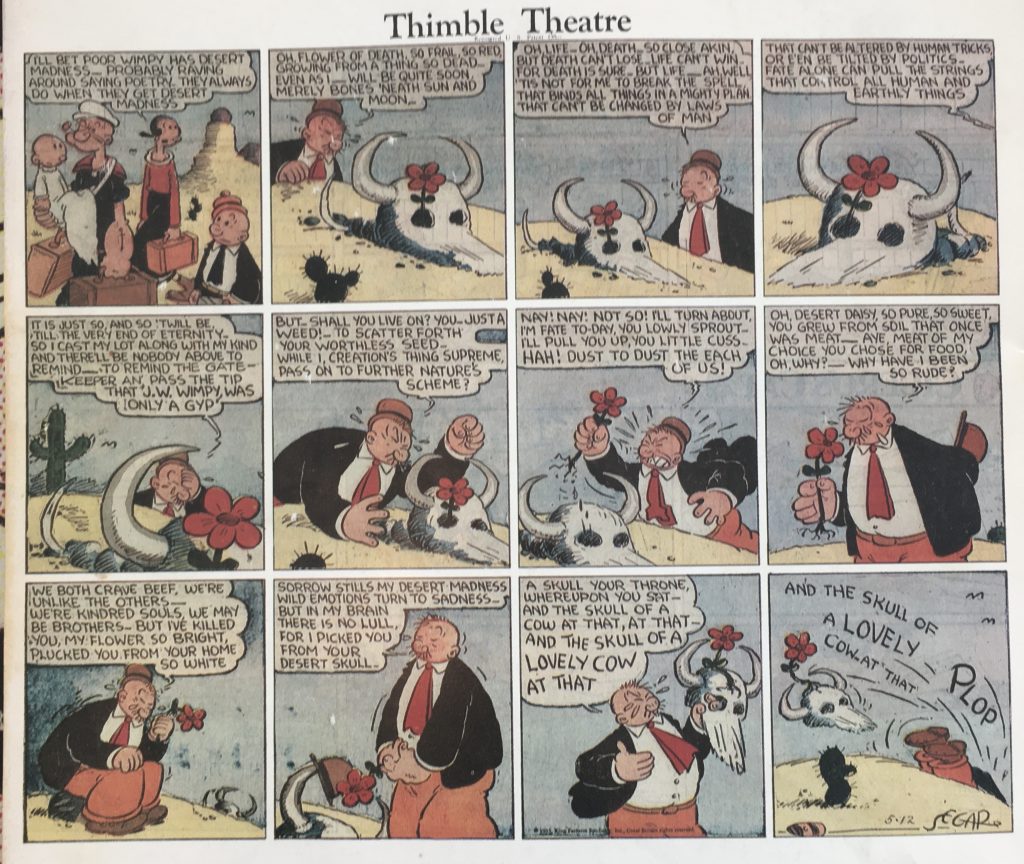

And Popeye’s surrounded by characters who are every bit as well realized. Most of all, there’s J. Wellington Wimpy, who’s a minor sideshow in the cartoons but who frequently threatens to take over the strip as Popeye did before him. The Jewish Segar created the perfect expression of one of the great stock characters of Yiddish folklore — the schnorrer, the well-spoken chiseler who always gets his way no matter how unlikely it seems. W.C. Fields turned down an offer to play Wimpy because he couldn’t see himself in the role, and the man was never more wrong in his life.

Fittingly, given his origins, Wimpy’s nemesis is the closest thing to an explicitly Jewish character in the strip — the bearded George W. Geezil, “shoe-gobbler,” whose phonetic English Segar delights in exploring. His identity became much more explicit in the movie, where Robert Altman replaces his derby hat and bald head with a Hasidic hoiche and earlocks.

The cartoons were too dialogue-light and action-heavy to do Wimpy justice, but when Segar cuts loose with his zeppelin-size word balloons, Wimpy really sings. In one oversized Sunday episode, he literally waxes poetic.

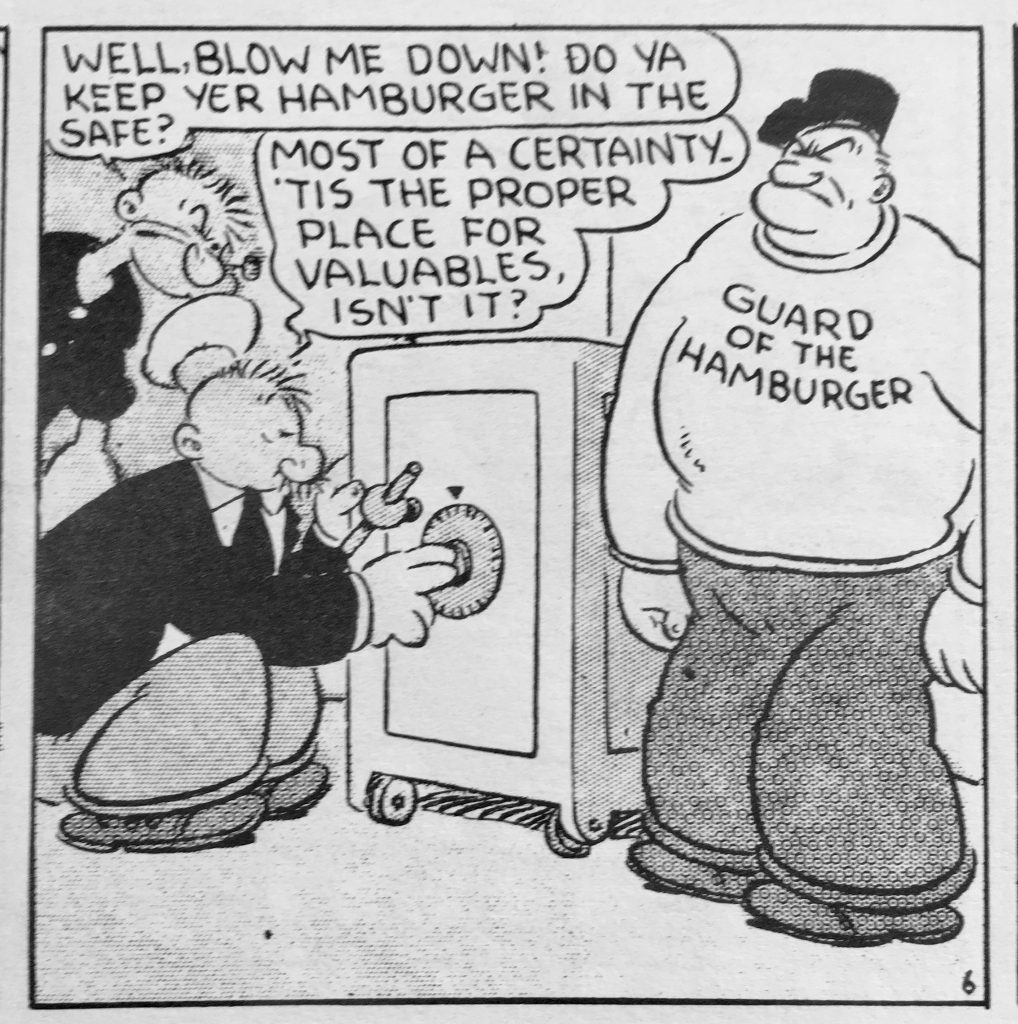

And of course, there’s Wimpy’s famous appetite for hamburgers, for which he’ll gladly pay you Tuesday, and which he gets to indulge when he uses his gold-prospecting fortune to but his own restaurant.

For all that, Wimpy’s physicality is often the funniest thing about him. No visible mouth, eyes as little horizontal lines, and, as Donald Phelps points out, you rarely even see his hands — he further adds Wimpy seems to be trying to retract into himself, interacting with the world as little as possible. This all makes Wimpy a hilariously stoic contrast to whatever chaos he endures or causes.

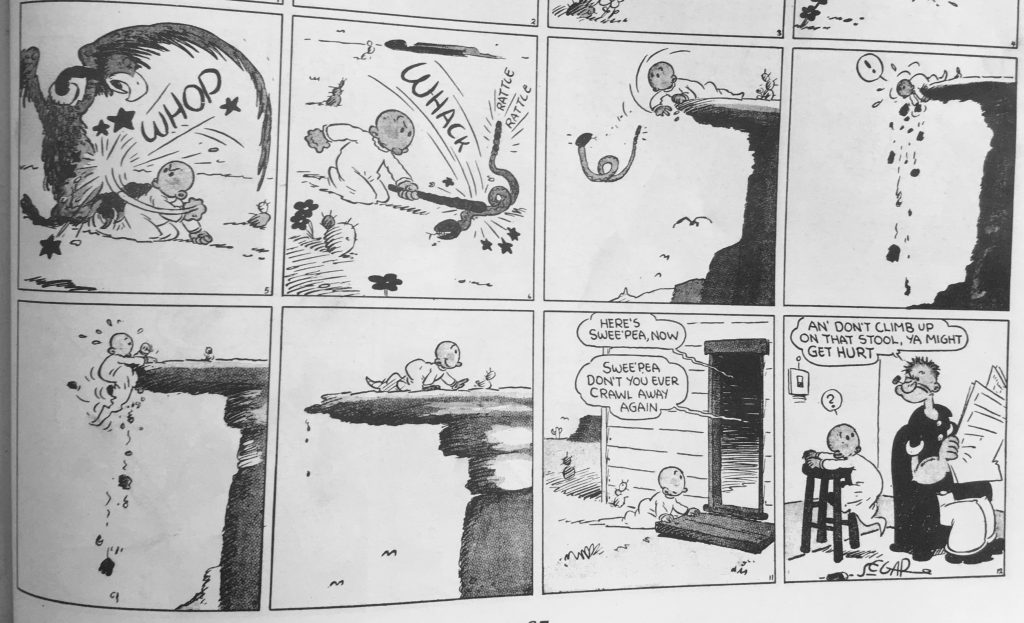

So is Popeye’s “adopted boy kid” Swee’pea, who’s obviously inherited his father’s toughness. Imagine Baby’s Day Out, if Baby’s Day Out were actually funny.

And that’s just the start of the vivid players Segar populates his thimble-sized theater with. After years of absence, Segar finally finds a way to make his original star, Castor Oyl, interesting enough to share the stage with Popeye. Before, he was just a generic everyman, and his few character traits — spitefulness, cowardice — were all negative. Worst of all, he spends most of his time with Popeye insulting him, apparently resenting the growing power shift. Castor reappears as a Sherlock Holmes-style Great Detective, able to summon a vast network of apparently superhuman agents with just a whistle.

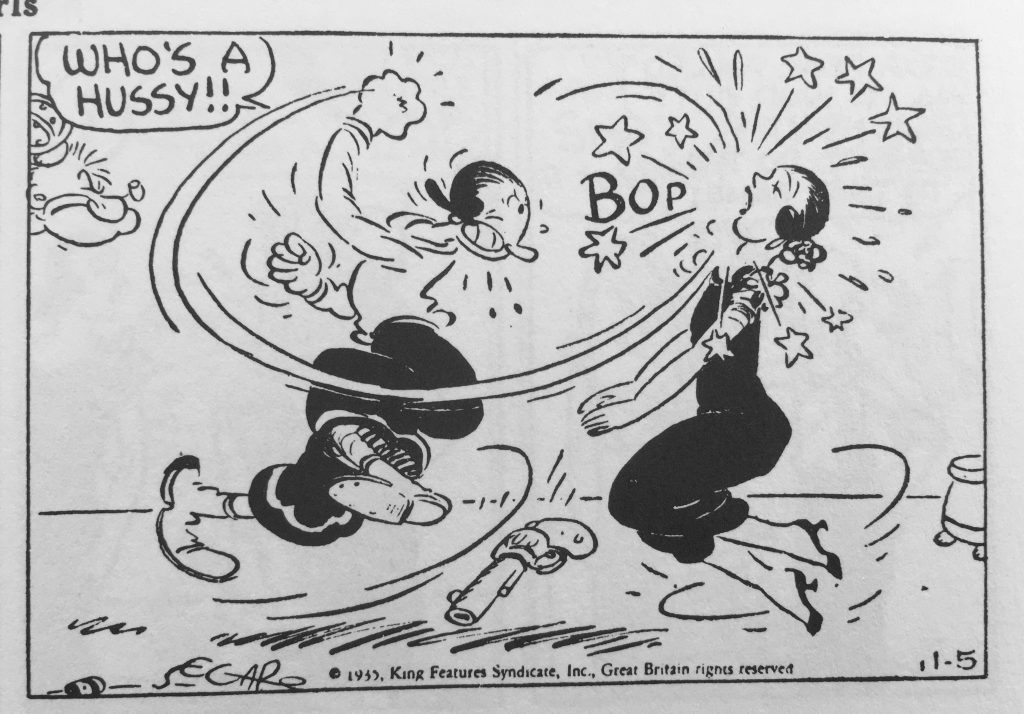

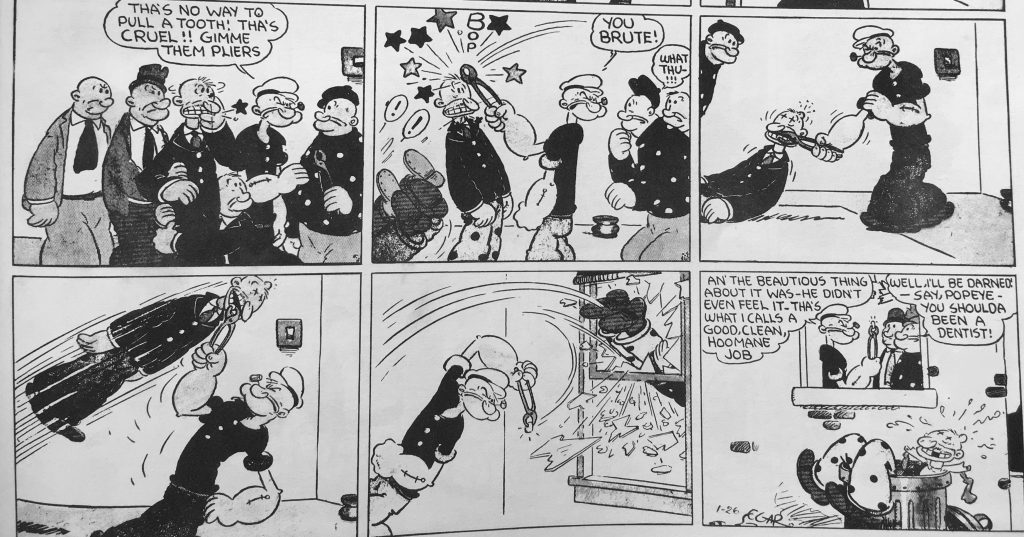

Segar can’t compare to Alex Raymond as a draftsman. He had to take a correspondence course after his first attempts at cartooning stalled out, and if you look at his early cartoons (including some starring Charlie Chaplin!) you can see he took years to get the hang of it. But Segar knew how to make his limited skills count. He was ruthless in his simplicity — notice how few of his cast have hair unless it’s essential to their character. And he could go the opposite way when the situation called for it — his wild takes have so many exclamation marks and sweat beads flying off his characters’ heads you wonder if he just went nuts on it until his assistants had to take his pen away and hold him down.

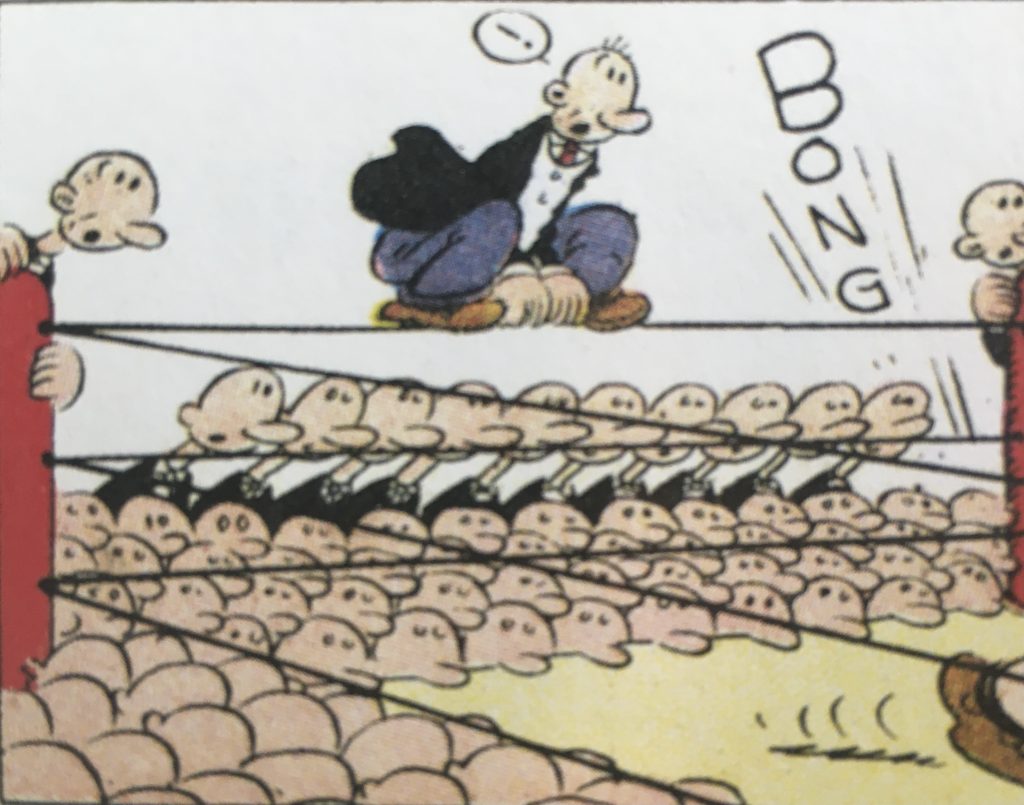

And Segar found the funniest possible way to draw anything. His crowd scenes are especially striking. When Popeye boxes, his audience appears as thousands of little head-globes, their pickle-shaped noses protruding into the ring like Kilroy.

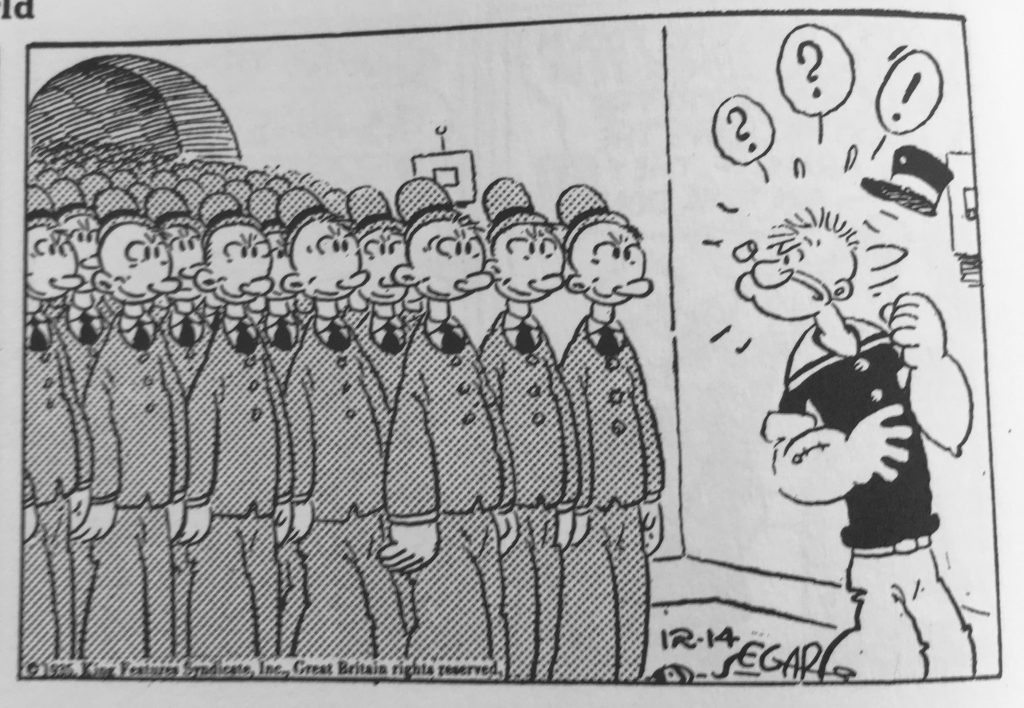

The citizens of Popeye’s kingdom of Spinachova are all identical, which may sound like a lazy solution, but the crowd of bald-headed gangly geeks, like male Olive Oyls or adult Swee’peas, never stops being funny. And Segar’s shorthand — hundreds of little curves, spaced further out as they recede into the distance — is beautiful in its simplicity.

Best of all are the agents of Castor Oyl’s detective agency. They move as a mass, radiating out from behind another character’s back like a turkey’s tail before he sends them flying in a starburst of action.

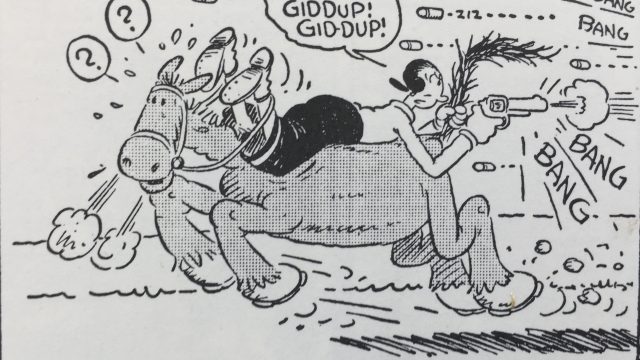

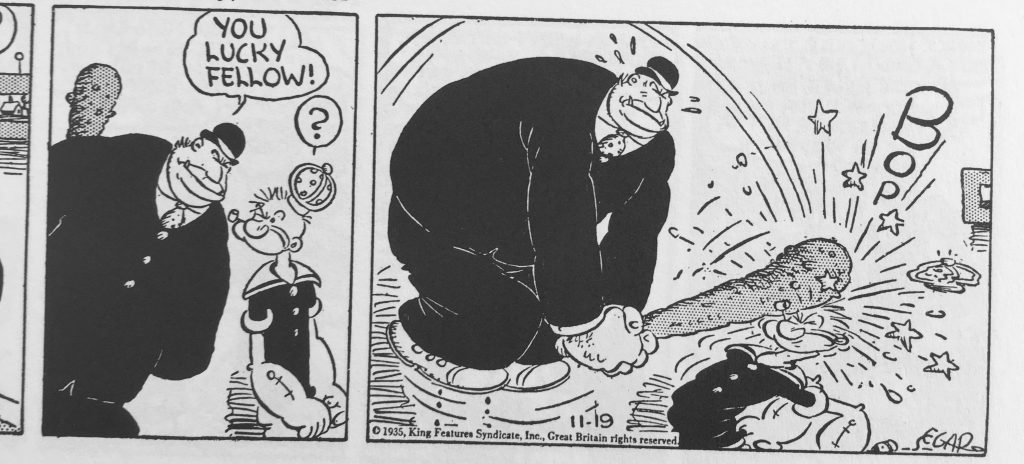

Segar’s action scenes are so animated they practically make the Fleischers’ animated adaptation redundant.

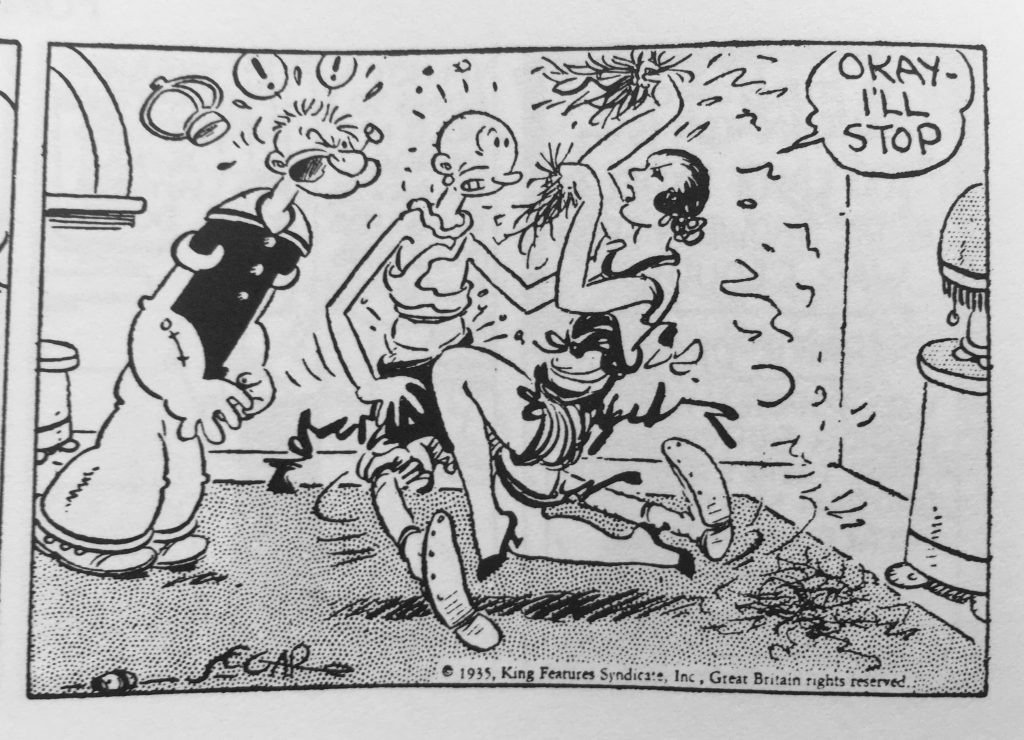

The most recent round of reprints come in intimidatingly oversized volumes that show off Segar’s Sunday funnies in something like their original dimensions. Sadly, this means stacking the dailies so high that they have to be shrunk to the size of a modern strip to fit. You’ll have to squint to read the balloons at that size, but it’s worth squinting even further to appreciate Segar’s fluid line, expanding and contracting on a dime. Just look at this panel which goes above and beyond the prurient interest (Popeye looks away so he “won’t get embarassik”) with Segar’s cleanly frantic linework.

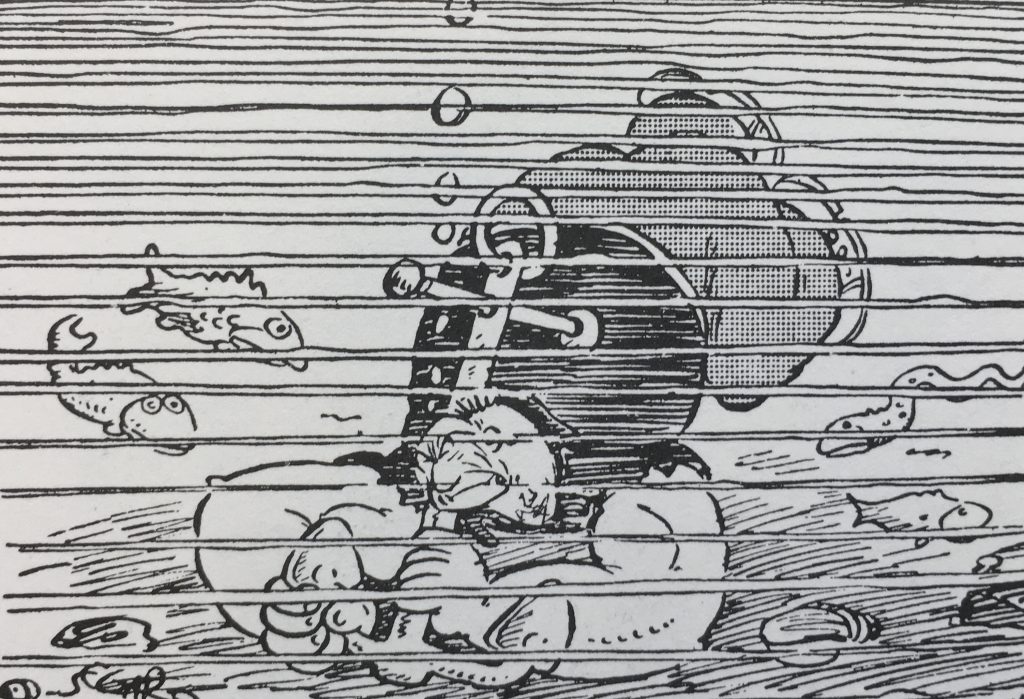

Or look how effectively he plunges readers underwater with just a few well-placed lines.

On the other hand, he could also use thin, airy lines for dynamic effects.