How’s this for serendipity: exactly a week ago today, in the midst of heightened tensions over a new round of sanctions and looming military-political gamesmanship over Venezuela, Moscow’s Interfax news service announced the creation of a joint Russia-U.S. spaceflight project to send tourists to the International Space Station by 2021. Call it what it is — further evidence of a frivolous elite class untouched by the zigs and zags of geopolitics — but it also represents the next stage of a long history of Russian-U.S. cooperation in space, a history that sometimes belied the reality of earthly politics. After all, it took less than a decade to go from the Cuban Missile Crisis to the first overtures of cooperation between NASA and the Soviet Academy of Sciences: even during the height of the Vietnam war, the idea that these enemies could work together off-planet persisted.

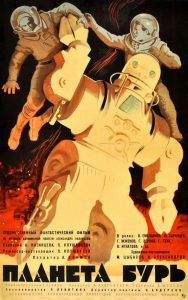

Science fiction had gotten there first, of course, like the movie at the center of today’s discussion, Planet of Storms. It premiered a few months before the Cuban Missile Crisis with a fantastical vision of Soviet-American space cooperation. It was, like a number of other Soviet SF films (Icarus X-B1; The Heavens Beckon), eventually introduced to Americans via Roger Corman and a litany of cuts and re-shoots, in this case leading to two separate films: Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet (Curtis Harrington [!!!], 1965) and Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women (Peter Bogdanovich [!!!], 1968).

Planet of Storms itself was tied to a novel, Alexander Kazantsev’s confusingly named Grandchildren of Mars (1959), confusing because it describes an expedition to Venus. It belonged to the sudden burst of space-travel fiction, led by Soviet author Ivan Efremov, that arrived with the Khrushchev Thaw (the genre had largely atrophied during the late Stalin period). This slim window between the reopening of outer space fiction and the launch of Sputnik, the first time we got an actual view of Earth from above, allowed the imaginations of its authors to run rampant: Kazantsev combines the requisite Marxist historiography with quasi-mystical mumbo-jumbo about the origins of life, square-jawed Americans with their very practical robot sidekicks, and planets stalked by dinosaurs and diaphanous alienesses.

One thing the genre couldn’t escape, however, was the shadow of death, which seems to figure more obsessively in space adventures than in the earthly counterparts, not just because of the real danger of space travel (which we had only just begun to understand in its fullness), but possibly for deeply rooted cultural reasons, as well. Here’s Nabokov in 1952, exactly a decade before Planet of Storms:

Deep in the human mind, the concept of dying is synonymous with that of leaving the earth. To escape its gravity means to transcend the grave, and a man upon finding himself on another planet has really no way of proving to himself that he is not dead — that the naive old myth has not come true.

Kazantsev’s novel is no exception: a third of the cast dies in the first two pages. Somewhere in the distant future, a joint space expedition of Soviet, American, and Other scientists are en route to Venus to search for the building blocks of life. Alas, disaster strikes: with no advanced systems for predicting the chaotic currents of inter-space debris, the ship Dream is struck by a meteorite and destroyed, taking its entire crew with it. Now the crews of the Soviet-led Knowledge and the American-led Prosperity face a difficult decision: to return home, given the lack of logistical support that Dream was meant to provide, or to risk a daredevil landing and hope Nothing Goes Wrong, that they can land on the surface, conduct experiments, and return to an orbiting ship and so make it safely back to Earth with their research.

It’s a bold opening that director Pavel Klushantsev almost immediately flubs. The opening shots of space, with the ships floating tiny and silently, is quite good — as is the first image of Venus, smoky and mysterious. The three ships are now, mercifully, given the less-Symbolic names of Sirius, Vega, and Capella. Before we meet any characters or see any interiors, the voice of a Moscow-based radio announcer (?) proudly assures his audience that the ‘nauts on all three ships “are in perfect health!” just as a cartoon meteor turns Capella into cartoon dust. Kazantsev is far from subtle, but Klushantsev handles this moment with the grace of a rhinoceros.

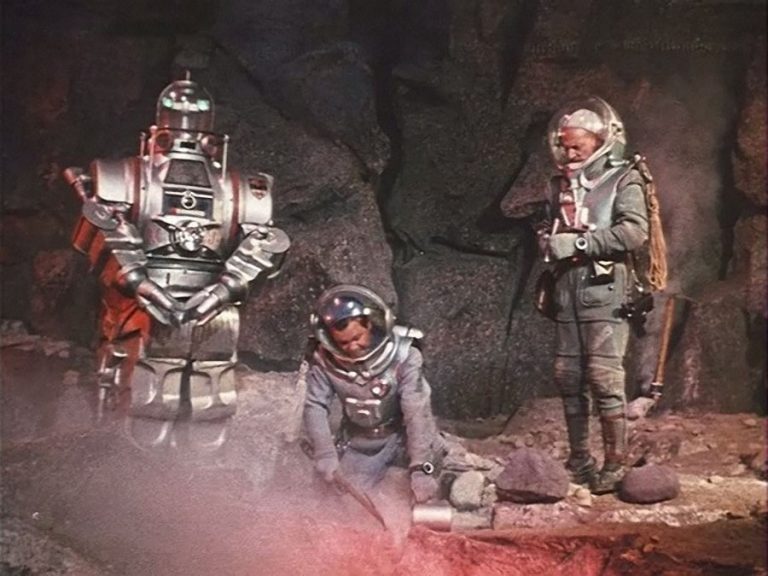

Now we enter the ships, which are in a state of mourning. On the Sirius we have the Soviet crew, the weary captain Vershinin (Vladimir Emelyanov), the hotheaded young Alyosha (Gennadi Vernov), and the other guy Bobrov (Georgii Zhzhonov). On the Vega we have… still a mostly Soviet crew, led by Ivan Shcherba (Yuri Sarantsev), radio operator and Ivan’s partner Masha (Kyunna Ignatova), and the cadaverous American “Allen Kern” (Georgi Teich, played about as convincingly American as most Americans play Russian characters in our own movies). “Kern” also has a friend, his robotic sidekick “John”. We don’t spend too much time with them on the ships, which is for the better, since the interiors represent an utter failure of production design, lacking anything like the imaginative leaps of Klushantsev’s earlier and far superior SF film Road to the Stars (1957, based on the hard SF stories of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky).

The fateful decision now arrives: will the surviving scientists, three to a ship, make the risky landing on Venus or wait the four months for the relief ship Arcturus to arrive? The crewmembers discuss, and in the end, the Vega’s Ivan agrees to risk an unplanned flight carrying himself, “Allen Kern” , and “John”, leaving behind only Masha, the mission’s sole woman, to keep vigil in orbit and monitor their progress. (“But I worked for so many years to get here” she protests, before all the men abandon her to her custodial role.) I’m not sure Kazantsev handles this much better, but his version is at least more colorful: his (American) Mary is a daredevil heiress whose father financed the expedition, unlike the somewhat featureless (Soviet) Masha. Both iterations of Mary/Masha will end up endangering the mission with their irrational womanly behavior, and both book and film have the exasperated men shrug at the utter incomprehensibility of the female brain. This, in a piece that involves dinosaur aliens.

Yes, dinosaur aliens! As dull as the opening scenes are, Klushantsev’s take on Venus is a delight, a mashup of Star Trek (avant la lettre) exteriors and Universal rubber-monster suits alongside sudden floods and lava-spewing eruptions, and an especially delightful sequence under the ocean that succeeds at feeling “alien” where everything else feels weird but in a comfortable, fully familiar way (credit Arkadi Klimov’s camerawork and aquarium rig). The two crews are separated and must find each other on the hostile planet before the orbiting Vega runs low on fuel. They fight and evade monsters! They travel by floating (and submersible) car! They find what may be the ruins of an ancient civilization! Heroics are displayed, both by man and robot! The speculative, fantastical possibilities of Kavantsev’s novel finally unleash Klushantsev’s imagination and technical cleverness.

There are also moments of quiet, contemplative beauty, as when Alyosha sits on the rocky shore under a Venusian sunset wondering about the possibility of interplanetary civilizations, or a when a mysterious voice seems to call out to them from the distance… I don’t want to give away all of Planet of Storms’ secrets, except to say that Klushantsev greatly improves on the novel’s ending by saving his very best shot for last, a suggestive moment filmed in a distorted reflection to tell the audience what we need to know without giving away too much (Kazantsev gives away too much, then keeps going).

Like no few films of its era and genre, Planet of Storms is corny but earnest, a far cry from the Corman-branded hack jobs that trade the stiff attempts at philosophy for red-meat entertainment. But as much as it’s tempting to do so, given the time and the results, I’d hate for us to read that as some sort of unintentional metaphor for Russia-U.S. relations, then or now. That’s the kind of over-obvious but under-baked idea you might find in a Kazantsev novel.

- There are a few versions of this on Youtube, and this one seems to have the best English subtitles (tho the overall transfer is not as clean as some of the others. Of the two American cuts, Harrington’s is mostly inoffensive, keeping most of the original intact, dubbing the Russians (and deleting the philosophy), adding a Ground Control in the form of Basil Rathbone, and recasting Masha (now “Marsha”) in the form of Faith Domergue. Bogdanovich’s version adds a coven of skimpily clad mermaid women.

- Fun (?) fact: Planet of Storms was almost derailed when Soviet Minister of Culture Ekaterina Furtsova objected to the way the character Masha was handled. She criticized a teary-eyed moment, saying “A Soviet woman-cosmonaut cannot cry!” (Incidentally, Valentina Tereshkova’s historic space flight was still one year away.)

- There are actually multiple versions of Kazantsev’s novel, written and re-written as the film was in-progress. The more elaborate version takes the action much further away: the team travels instead to the Sun-like 82 G. Eridani, where a set of planets similar to our own awaits (Kazantsev assures us that other planetary systems have formed just like ours due to “universally shared laws of nature”, where, citing Party-approved Friedrich Engels’ ruminations on biogenesis as a scientific rule, life must have formed as well.) As this system appears younger than our own, their destination is not a second Earth but “Venus-2,” i.e., he didn’t have to change much.

- Despite the stereotype that hard SF is stiffer and more serious than the more fantastical wing of the genre, I cannot recommend Klushantsev’s loopy and entertaining Road the Stars highly enough. Part biopic of the brilliant Tsiolkovsky, part science lesson, part speculative fantasy, it dances between animation, reconstruction, and goofy flights of imagination without skipping a beat. If you can deal with clunky English subtitles, you can watch the entire thing here. Klushantsev’s particular alchemy in this film was so successful he would try to recapture it in later work, including The Moon (1965) and Mars (1968). Funny that the pure fiction of Planet of Storms would prove a much more restrictive collar on his imagination.