It’s the end of the things you know / Here we go.

When Sony agreed to go into business with Revolution Studios in 2000, they were in bad shape. As the New York Times reported in a 2006 postmortem on Revolution, Sony ranked #7 among the major studios for domestic box office in 2000, successes like The Patriot and Charlie’s Angels only doing so much to cover up embarrassing losses like What Planet Are You From? ($14.1 million, $60 million budget) and I Dreamed of Africa ($14.4 million, $50 million budget). With that in mind, an offer from someone as seemingly reliable as Joe Roth seemed like a good investment. And it was a good investment at first. For as much as Revolution’s initial 2001 slate seems disappointing viewed on its own, it was a godsend to Sony in a dismal year. Two of Sony’s three $100 million grossers that year came from Revolution (the third was A Knight’s Tale), and none of their failures came close to matching what Sony lost on Ali ($87.7 million, $107-118 million budget) and especially Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within ($85.1 million, $137 million budget). Then, in 2002, Sony had two of the five highest-grossing films of the year, Men in Black II and the absolute juggernaut of Spider-Man. Suddenly, Sony was back on top and Revolution was no longer the one-eyed man leading the blind. Now it seemed like Revolution was just dragging Sony down, especially with the multiple disasters they saddled Sony with in 2003. Even when Revolution succeeded in not embarrassing itself in 2004, Sony had Spider-Man 2 that year to make Revolution’s successes seem paltry.

It wasn’t just Sony’s fortunes that were changing. The film marketplace was beginning its shift away from the star vehicles Revolution was so often peddling and towards too-big-to-fail franchises, leading to the increasingly barren cinematic landscape we have today; the final, possibly irreversible turn into that began just months after Revolution shuttered, with the releases of Iron Man and The Dark Knight. Also occurring soon after Revolution’s closure was the collapse of the DVD market, previously a reliable source of income even for the studio’s flops (and the only reason the Hellboy sequel got made). Even if Revolution had been turning out gold, their time was just about up before it even began. Joe Roth said this in a 2011 interview with TheWrap:

“The assignment made sense going in,” Roth said. “Midway through it was clear the marketplace was changing. And there was no apparatus, even if I could figure it out, to change it. So I stopped it, a year before I had to.”

In this light, it’s tempting to be sentimental about Revolution, now that their bread and butter of junky comedies and standalone action movies is exactly what’s missing from movie theaters (it’s all gone to streamers now). But one can only cut Revolution so much slack before they manage to hang themselves anyway. One would think they’d stumble into some kind of understanding of what they did wrong by their final year in existence, but nope, it’s the same mistakes all over again; cut-rate crap and needlessly inflated budgets. As noted by The Ploughman in the comments of a past article, Revolution comes to represent what really killed the mid-budget studio movie: not audience apathy, but shoddy products that audiences didn’t want to see, which the studios then interpreted as apathy towards non-megabudget spectacles in general.

In February 2005, after the success of Are We There Yet?, Revolution announced its next project for Ice Cube and his production deal, a remake of the Cary Grant comedy Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream Home. Blandings isn’t the most well-remembered or -liked Cary Grant movie, but it does have a solid studio-comedy premise; guy wants to build a house for his family, hijinks ensue. Blandings doesn’t really have much name-recognition value, and with its production coming right as Revolution was closing its doors, it was decided to wring a quick buck from Blandings by retooling it into a sequel to one of Revolution’s actual hits. This is how it became Are We Done Yet? ($58.4 million, $28 million budget), a title Revolution surely knew would be the header of every bad review coming their way.

Are We There Yet? did not set a very high bar for a sequel to surpass, and Are We Done Yet? crosses that bar in its first four minutes. There, we get a cute animated credits sequence with a cartoon Ice Cube trying in vain to fix various problems with the credits, sometimes interrupted by cartoon animals. I chuckled a few times at them, which is more than I chuckled at the entirety of the first movie. Once the movie proper started, I chuckled a few more times at John C. McGinley’s performance as the contractor/city inspector/real estate agent who keeps tormenting Cube (McGinley replaced Thomas Haden Church after Blandings was retooled, and given Church’s bizarre performance in fellow real-estate-focused kids movie We Bought a Zoo, McGinley is probably an improvement). This should put it above the, again, completely laugh-free first movie, but it manages to squander that advantage by somehow being even lamer than its predecessor. Miller made the great point in the comments of the 2005 article that Are We There Yet?, for how assembly-line mediocre it is, was probably successful because taking a long, agonizing road trip is such a universal experience that even the dumbest version of that plot will ring at least a little true. Granted, I have never been involved in renovating a house from scratch, but Are We Done Yet? seems fully disconnected from any notion of real-life, from its cartoon house-falling-apart gags to its nonsense subplot about Cube trying to start a sports magazine (called “All About Sports“) on the back of a Magic Johnson interview he doesn’t have. This is just a dumb sitcom released theatrically, with Ice Cube behaving like an oaf to his family for most of the movie before arbitrarily learning his lesson at the end. I can’t believe I’m giving credit to the character writing of the first movie, but that movie’s bog-standard “guy who hates kids learns to care for kids” arc still gave you more to hang onto than this, where Cube just antagonizes his new family for no real reason until he learns the true value of family and blah blah blah. It is a nauseatingly phony, phoned-in product even by Revolution standards, like an algorithm spit out a fully-formed family comedy.

2007 is the first year digital filmmaking really starts entering the mainstream on a major-studio level, and comedies (many of them Sony productions, including Walk Hard and Superbad) make up the bulk of studios’ early experiments with digital. Watching Are We Done Yet?, which was shot on good old-fashioned 35mm by Clint Eastwood DP Jack Green, shows why studio comedies were so attracted to digital, because it’s the best format for the overlit, spray-tanned aesthetic favored by these movies. The texture of film adds nothing of value to images this glossy and flat, why not cut out the middle man and avoid it entirely? Are We Done Yet? looks like it has been made by people who can’t wait for digital to get advanced enough that they can shoot on it instead; if it was made just one year later, it may very well have been. In this form, it is a bastardization of anything that could be appealing about 35mm, and it looks significantly uglier than any of the high-profile digital movies of this era. There was a chance you could go to a theater and see both this and Zodiac, to see the death knell of the old format and one of the earliest high-water marks of the new format.

Let’s think back one last time on the three A-listers who signed three-picture deals with Revolution at its start. Adam Sandler fulfilled his end of the bargain and then some, he starred in three movies for them and produced three others. Julia Roberts made two movies for them and that was that (not for lack of trying). And Bruce Willis seemed like he was going to tap out at one movie until, like a kid turning in a late homework assignment on the last day of school, he made one more at the ass-end of Revolution’s existence. That movie was Perfect Stranger ($73.1 million, $60 million budget), which had been kicking around Revolution for years before it finally went in front of cameras. It was first announced in 2000 as a Julia Roberts vehicle and the next year Philip Kaufman signed on to direct it. From there it passed through several writers and Kaufman bailed, fulfilling his desire to make a shitty studio thriller by making Twisted instead. Then it passed from Roberts to Halle Berry (finally paying Roth back after dropping out of Gigli) and from Kaufman to James Foley, at which point Willis was added and it finally went into production in 2006.

If you know about Perfect Stranger, it’s probably because of its twist ending, the kind of Donald Kaufman bullshit that took Hollywood by storm after The Sixth Sense. But Perfect Stranger isn’t really the psychological thriller suggested by its twist, it’s more an idiotic cyber-thriller that makes more sense as a 2000 script than it does as a 2007 production. This is the kind of movie with extended setpieces of characters engaged in chatroom conversations and saying everything they’re typing out loud (Giovanni Ribisi even installs something on Halle Berry’s computer that reads the other person’s messages out loud), the kind of movie where the most clever fake website name they could come up with was “IOL”. That stuff is stupid and worst of all completely flat, you can’t even laugh at its techphobia when it’s so stultifying to watch. For a movie built around finding a vicious murderer, there’s no sense of danger here, just dull corporate intrigue and even duller scenes of people staring at their computers. Going into this knowing that Bruce Willis will not be the killer makes it obvious how little the filmmakers invest in making Willis a tangible threat, Berry doesn’t seem remotely worried to be in his presence and so we’re not either. If your misdirect is this uncompelling, even a clever twist wouldn’t be worth the wait, and this one is insultingly dumb (and also offensive in how it shoehorns child abuse into a story that has nothing to do with it).

Berry and Willis are the marquee names and they’re both fine, I guess. There’s a real scarcity of talent as you go further down the cast list, roles that could be filled by reliable character actors are instead played by nobodies who you forget about the second they’re out of frame. The only semi-recognizable face besides the leads is Gary Dourdan, who gets a two-scene part that’s completely extraneous except as an unconvincing red herring. But none of those people do quite much damage to the movie as Giovanni Ribisi does. Ribisi is an actor I generally like but understand people having issues with, his nasal whine and tics-a-plenty are just as likely to turn people off as draw them in. But here he’s so awful it makes you question what worked about his past performances, if Sofia Coppola and Steven Spielberg had to beat the mannerisms out of him to make him appear like a normal human. Admittedly, any actor would be at a loss to play this character, who oscillates nonsensically between being annoying comic relief, a crusading investigator, and a sex creep from scene to scene. Ribisi actually adds some consistency to the character by making him an obvious scumbag from scene 1, even though the movie wants you to think he’s just the goofy sidekick. We’re expected to believe that Berry and Ribisi are the best of friends and I don’t buy that Berry would even pretend to be nice to someone who crosses this many personal boundaries this aggressively under the guise that he’s just kidding around. When he tries to be funny, he’s nails on a chalkboard, and when he’s revealed to have constructed a sex shrine to Berry, it’s not shocking because of course he has. And when the ending involves Berry framing him for murder, it’s hard to care one way or another because it’s the very least he deserves.

First, I want you to consider every piece of shit that Revolution handed Sony and Sony could stomach distributing. Now, I want you to consider the possibility of a Revolution movie that Sony rejected because having their name on it would make them look bad. This is what happened with Next ($76.1 million, $78.1 million budget), a Philip K. Dick adaptation directed by xXx: State of the Union‘s own Lee Tamahori; even at the very end, Revolution remained undefeated in not picking up on obvious creative red flags. It was originally scheduled for release by Sony in 2006 before they delayed it and then dropped it entirely in January 2007. It was then picked up by Paramount and released three months later, in a week where the studios joined together to dump their trash and let it get washed away by Spider-Man 3‘s release the following week. Next‘s competition that week was The Invisible, the Stone Cold Steve Austin vehicle The Condemned, and the last of the wide-release Jamie Kennedy vehicles, Kickin’ It Old Skool. All four opened lower than the third weekend of Disturbia.

2007 represents the last gasp of Nicolas Cage as a respected, bankable actor and not as the meme guy, a characterization he struggles to overcome even now that people like him again. The Wicker Man was the year before but that gained its power from years of YouTube videos, while this year had Cage’s last successful studio star vehicles in Ghost Rider and National Treasure: Book of Secrets. His eccentricities could still be sold as endearing quirks as they are here, where Cage restrains himself and mostly plays soulful as a low-level clairvoyant who can see exactly two minutes into the future, a brooding romantic doomed to lead the love of his life into danger. This isn’t often included in those YouTube compilations of crazy Cage moments because he’s taking it seriously (even when he seems to be ad-libbing nonsense, like a story about a Magnolia-esque rain of fish, he comes off as just trying to make honest conversation), and the movie only occasionally rewards his efforts. He does have a little fun at the beginning, where he’s made a career as a decent-enough Las Vegas stage magician and runs minor card scams in his free time. This is a starting place infinitely more interesting than where the movie takes this character, making him the emissary for a European nukes plot I could not care less about. While I was pleasantly surprised that Cage’s sleight-of-hand skills came back at all after that side of him is dropped, it would have been even better if he was pulling Ricky Jay shit during action scenes.

Once the plot of this movie kicks in, the only remaining points of interest are in how Tamahori visualizes Cage’s abilities. I didn’t have much good to say about the direction of xXx: State of the Union, but he has some genuinely clever ideas here, like a sequence where multiple Cages split from each other to assess the future from every potential turn or decision, or ending with a negation of an action setpiece rather than with the setpiece (like Breaking Dawn Part II later did to extraordinary effect). I was especially impressed by a meet-cute sequence near the half-hour mark that turns into Cage going through multiple futures of bad pick-up lines trying to find the right one to use on Jessica Biel. Unfortunately the romantic side of Next falters dramatically after that scene, with Biel’s sub-zero charisma making up for Cage always being watchable. And the action side is even worse, often marred by what I must now consider a Lee Tamahori auteurist signature: sequences built around dogshit, laughably cartoony CGI. This was bad enough in 2001, in 2007 it’s just embarrassing. And the same can be said for the inexplicable, half-assed imitations of Seven‘s opening and closing credits, which make no sense with anything in the movie they bookend.

Next marks the fourth of four Julianne Moore vehicles produced by Revolution, which includes one of her very best performances (The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio) and maybe her very worst (Freedomland). Something about her performance in this, as an FBI agent hot on Cage’s tail, initially struck me as odd in a way I couldn’t put my finger on. Eventually I realized what she was doing: a Catherine Keener impression. Her deadpan intonations and take-no-bullshit bluntness seemed to belong to a more regularly comedic actress like Keener or Parker Posey, someone who can put a fun spin on stock gruff dialogue (they even look to have dyed Moore’s hair to be closer to those actresses’ brunette manes). Moore can do a lot but this is an unnatural fit that she cannot make work. She’s not the only one floundering here, the entire cast besides Cage has been directed to amateur-hour performances that just make the thudding conventions of its arms-war plot even more obvious (Cage is immune because he only takes direction from himself). I’ve never been impressed by Biel so this could just be a normal performance from her, but I’ve not seen Thomas Kretschmann directed to such a tone-deaf performance, it might as well be speech-recognition software reading his vague Eastern European baddie dialogue. Even a brief Peter Falk performance leaves absolutely no impression, he appears in and disappears from the movie with equally little explanation.

Next is certainly not good, and much of its second half is almost impossible to pay attention to, but I don’t get being any more opposed to releasing it than just about any other movie Sony put out for Revolution. They should’ve sucked it up and released it, it’s not like they avoided a black eye when they still distributed movies like, say…

Are We Done Yet? isn’t the only quickie sequel that Revolution pumped out in its last hour of existence. Since almost immediately after Daddy Day Care‘s release, Revolution was trying to make a sequel but Eddie Murphy just wouldn’t agree to do one. So instead of only making a Murphyless Daddy Day Care sequel or, god forbid, not making one at all, Revolution decided to bring back none of the original cast members and go full-steam-ahead on Daddy Day Camp ($18.2 million, $6 million budget) with a cast of nobodies and Cuba Gooding Jr. in the Murphy part. As one can probably guess from that paltry budget, Daddy Day Camp was originally intended to go straight-to-DVD, but it instead got a theatrical release, Sony probably feeling it could make at least a little money off name recognition and children being stupid. It made exactly a little money and that was that.

When we last met Cuba Gooding Jr. in this series, he was at the very tail end of the period when he could lead a studio movie with the expectation that it would make money, a period that Radio ended in ignominious fashion. He had already sunken pretty low by the time of Daddy Day Camp but the bottom completely dropped out after it, where 2 out of his next 13 movies received even the most perfunctory theatrical release (and one of those two was American Gangster, definitely not a vehicle for him). Even aside from him seeming to be an awful human being, his performance in Daddy Day Camp makes a very convincing case for his career deserving to go into the trash heap. Replacing Eddie Murphy, even Eddie Murphy long past the point when he was a comedic lightning-bolt, is a tall order for any actor and Gooding answers the challenge with an even worse version of his usual mannered mugging. Murphy certainly played flustered in response to the first movie’s hijinks, but those responses were always recognizable as, you know, adult human behavior. Gooding, meanwhile, reacts to this movie’s mischief by practically going crosseyed at every moment. It doesn’t make sense that a person ostensibly living in the real world would behave like this, and it really doesn’t make sense that somebody who’s been running a day-care service for four years would be this ill-equipped for the struggles of handling children (if you’ve been leading a day care that long and still pass out when you see a dirty toilet, you’re very bad at your job). This is simply not the same character as the first one, they should’ve just changed his name and made this the sequel-in-name-only it already basically is.

Gooding escapes being the lowlight of Daddy Day Camp because everyone else involved with it is joining him in a race to the bottom. As I noted in the 2003 article, Daddy Day Care is a mediocre time-filler made entertaining because every part has been extremely well-cast. It’s one thing that none of those actors are returning for Camp, it’s another that no care was put into finding even passable substitutes for those actors. The replacement Jeff Garlin and Steve Zahn were clearly only cast because they kind of look like Garlin and Zahn if you squint, faux-Zahn in particular proves just how hard it is to emulate Zahn’s brand of sublime silliness without just being an annoying idiot (faux-Garlin, meanwhile, is now lucky that The Goldbergs proved there’s much worse options for replacement Garlins). Even the kid performances are a noticeable downgrade, I’m not expecting another Elle Fanning from the bunch but these brats couldn’t pass muster in a cereal commercial; most of what they have to do is scream and they can’t even do that convincingly. Camp is to date the only feature directing credit of Fred Savage, and if he can’t even direct adequate child-actor performances, the one thing you’d expect him to have experience with, it’s no wonder he crawled back to TV after this. Daddy Day Care director Steve Carr isn’t a comedic master (he also directed Are We Done Yet?, after all) but he at least made the best possible disposable studio product, while all Savage does is prolong the dumb, predictable beats until they go on for ages.

Daddy Day Camp does do one extraordinary thing, something I thought wouldn’t be accomplished in this series: it gives Tomcats a run for its money as the worst movie Revolution ever produced. It’s a surprisingly tough call to determine which one is worse, as they represent opposite ends of the unwatchable-studio-comedy spectrum. Tomcats is such a proudly regressive, mean-spirited work that one can argue its existence is a cancer on society at large, while Camp is so harmless (unless you’re offended by pee and puke and fart jokes) it becomes insulting, at least trying in vain to shock people requires some kind of effort. There’s a good argument for either, but I may have to give the bottom spot to Camp simply because I laughed once at Tomcats and did not laugh once at Daddy Day Camp. Congratulations to Bill Maher for producing this come-from-behind victory for Tomcats.

It feels like a cosmic accident that The Brothers Solomon ($900,000, $10 million budget) was allowed to be made at a studio level. It could only happen in this specific circumstance, where Revolution was too busy sulking about its imminent shutdown and past failings (or its very present-tense troubles with Julie Taymor, as I’ll explain next) to care that they were financing something this bizarre and wondrous. It was treated as disposable from its beginning to its end, set up at Sony’s disreputable genre wing Screen Gems rather than mainline Columbia and given an indifferent 700-screen release, where it peaked at #24 and was out of theaters in three weeks flat. Solomon came out just a month after Hot Rod, another fall-on-its-face flop from a 2000s SNL cast member (Bill Hader shows up in this too, in a wonderful scene where the only joke is that recumbent bicycles look funny), and they’re companion films for their brazen indifference to the conventions of studio comedies (and their soundtracks made up of only the cheesiest 80s hits, Solomon‘s use of “St. Elmo’s Fire” approaches Rake Gag repetition). Solomon‘s lack of the cult success that Hot Rod has enjoyed is likely because Hot Rod‘s more genial absurdity is easier to take than the bizarre, uncomfortable depths plumbed by Solomon.

Many contemporary reviews of Brothers Solomon bafflingly framed it as another in the long line of bad 2000s grossout comedies, seemingly only on the back of a scene set at a sperm bank (which is pretty tame in terms of what’s shown and joked about) and one misguided joke about a nice lady getting hit by a bus. Otherwise, the whole point of Solomon is that it’s not crude, it’s squeaky-clean. Psychotically squeaky-clean. Its opening credits are its mission statement, as the giant heads of Wills Arnett and Forte flash lobotomized smiles at every credit (in Comic Sans!) that passes them by, while the Flaming Lips sing about man’s inherent desire to do bad instead of good on the soundtrack. There is a point where golly-gee optimism is taken so far that it becomes not just absurd, but actively dangerous and terrifying. The brothers Solomon passed that point a long time ago.

Brothers Solomon was directed by Bob Odenkirk, who knows how to push standard comedic premises until they’re much more uncomfortable and much funnier as a result. Here, he and Forte (the sole credited writer) start with a premise that sounds like every hack arrested-development comedy of the time: two oddball brothers try to fulfill their dying father (Lee Majors)’s last wish of giving him a grandson. From there, they use every expectation the audience has for the kind of movie suggested by that premise as a weapon against the audience. Forte and Arnett aren’t eccentrics with hearts of gold, they’re menaces who the supporting cast is often rightly repulsed by (Arnett in particular has never looked or seemed scarier than he does here, his pasted-on grin and dead eyes give him the air of Patrick Bateman). They have no sense of how to behave in public and are often resentful of the people trying to politely deal with them, they earn every appalled reaction they’re met with (including from Odenkirk himself in a very funny, expectedly enraged cameo). The sharpest joke in the movie is the treatment of Malin Akerman’s character, Arnett’s love interest who’s never anything but courteous, kind, and 100% in the right, and is disposed of by both Arnett and the movie like she’s just another of the “bitch girlfriend” characters that filled comedies of this era. It effectively sells the awfulness of both Arnett and the studio-comedy model it has so little respect for (its only concession to formula is an out-of-tone sentimental coda), but more importantly it’s very funny.

If you’ll remember back to 2003, you’ll recall that Joe Roth, in the aftermath of Hollywood Homicide and Gigli, took final-cut privileges off the table for any future director working with Revolution. That didn’t matter the last few years because Roth mostly hired amiable hacks for these movies, but it became very important when Revolution decided to work with Julie Taymor. Taymor up to this point had experienced almost nothing but massive acclaim and success: The Lion King is still the highest-grossing Broadway show of all time, Titus was beloved despite being a bomb, and Frida managed both awards and financial success. I suppose it makes sense why Revolution would want to do business with her after Frida, as a way to give themselves a little much-needed prestige, but in most ways it doesn’t. If Roth was put off by the uncompromising auteur vision of goddamn Ron Shelton, how was he going to work with an artist respected specifically for her maximalist aesthetic? The answer is not well at all. Taymor’s Beatles musical Across the Universe ($29.6 million, $70.8 million budget) was greenlit and shot in 2005 for a fall 2006 release. That release date was pushed back when Taymor spent more than a year editing. Then things got very messy. Roth was not a fan of the cut that Taymor delivered, even after she trimmed it from its original 2.5-hour run time after initial test screenings. Since Taymor didn’t have final-cut, Roth took the liberty of screening his own cut of the movie, which was half an hour shorter than Taymor’s. Taymor didn’t like this one bit, threatening to take her name off the movie if it was released in his form, and their fight over the final cut became so public that The New York Times was reporting on it. This was not a fight that Roth wanted to be having at the eleventh hour of Revolution’s existence, when all he wanted was to not embarrass himself even more on the way out. He got some of the worst press of his entire career for this, and not just from people who wanted to protect Taymor’s vision. Soon after the NY Times article, Deadline‘s Nikki Finke wrote a hatchet job of Taymor full of unnamed sources calling her “a loon” (one person even takes Harvey Weinstein’s side against her in their fights over the making of Frida), and even in that context Finke still paints Roth as being a short-sighted moron “barely tolerate[d]” by Sony and its then-head Amy Pascal. His back against the wall one last time, Roth finally caved and released Taymor’s preferred cut in theaters, and nobody was all that interested in it; its perfunctory Costume Design nomination is the only thing keeping it from being a prime This Had Oscar Buzz candidate.

It feels good to side with an artist when they do battle with the studio, to know that art can triumph over commerce. Having watched 40-plus of the movies that Roth thought were A-okay to be released in those forms, I can’t say I’m sympathetic to his ideas of good art. But I also can’t say that this version of Across the Universe Taymor fought so hard to preserve is particularly good. It’s not the kind of not-good that gets solved by chopping half an hour off it, it would require a ground-up rewrite and reimagining to work. I can’t imagine a cut of this that doesn’t have the problem of being boomer nonsense at its heart, beloved Beatles songs soundtracking a Forrest Gumpian greatest-hits package of all the turbulent social and political events of the 60s. Occasionally this becomes outright offensive, like a scene that dramatizes the Detroit Riots for the sole purpose of giving the movie’s token Black character some characterization other than liking to play guitar (Taymor and Kathryn Bigelow, maybe rich white women aren’t the best choices to portray the Detroit Riots on film). But mostly it’s just tiresome and unimaginative, the same cliches about Vietnam and “the revolution” (hey, that’s the name of the studio!) that countless cable documentaries have beaten into the ground. And there had to have been better representations of 60s angst than the main characters they went with, two mopey losers with negative personality between them. These cardboard standees are played by Evan Rachel Wood, an actress I love who can’t overcome the lack of anything for her on the page, and Jim Sturgess, who’s cute but the most boring performer alive when you’re watching him here. The scenes of them together where they’re not singing Beatles tunes (and a few where they are singing Beatles tunes) are repetitive and dull, and they come as uninterrupted chunks between the expected gaudy Taymor setpieces. The gonzo vision that the studio didn’t want me to see shouldn’t be this sleepy for so much of its runtime. I was one of very few who cared enough to watch Taymor’s return from her Turn Off the Dark-induced stay in director’s jail, the Gloria Steinem biopic The Glorias. It has its own share of problems with 60s/70s cliches (plus biopic cliches, like an origin story for Steinem’s sunglasses) and it also looks much worse now that Taymor’s spectacle is coated in a plasticine digital sheen. But it’s still much better than this, committing much more thoroughly to its good ideas (even as its bad ones keep popping up) and not leaving its actors out to dry.

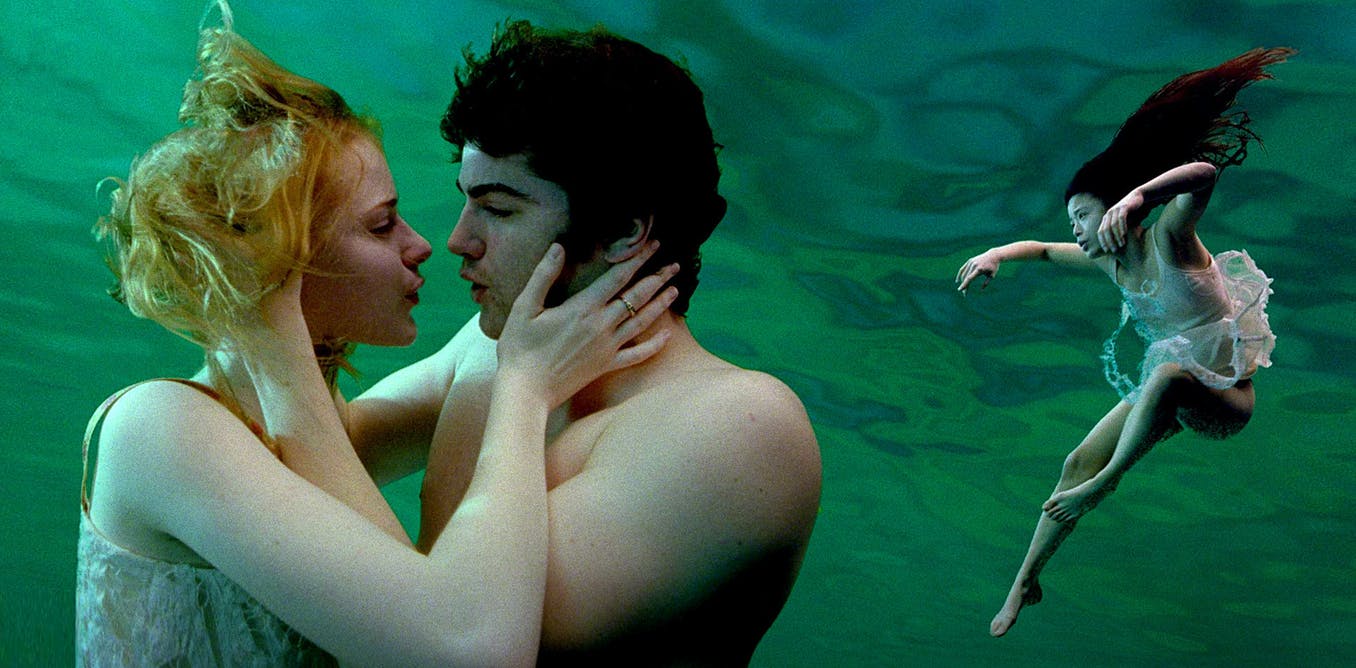

Across the Universe is a particularly frustrating watch because there are things it gets undeniably right. It’s almost entirely the musical numbers, which allow Taymor to indulge in her expected psychedelic imagery and go for exuberant displays of emotion and time and place rather than “I’m sad that you’re sad about Vietnam, Evan Rachel Wood”. Even then, the numbers can sometimes be pretty unimaginative interpretations of the songs, like Sturgess condescendingly yelling “Revolution” at Wood or the much-mocked sequence where “Dear Prudence” soundtracks a woman named Prudence being asked to come out and play (you see, she’s a lesbian and they’re asking her to “come out” of the literal closet she’s hiding in, har har). But sometimes Taymor hits the jackpot. Staging the giddy romance of “I’ve Just Seen a Face” in the bustle of a bowling alley is inspired, as is making “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” a Vietnam nightmare complete with menacing Uncle Sam and the heavy “she” being the Statue of Liberty, as is filming “I Am the Walrus” with the cheap-looking solarization effects of so much late 60s media and Bono playing Timothy Leary (whatever you think of him, Bono understands the gloriously ridiculous movie this can and should be, as does Eddie Izzard with her memorably grating take on “Being For the Benefit of Mr. Kite”). And even the movie’s detractors have to give credit to its version of “I Want To Hold Your Hand”, which slows it down to a crawl, foregrounds its “I’m gonna die if you don’t touch me” anxiety, and makes it an anthem for lesbian longing.

This is the way the Revolution ends. Not with a bang, but with The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep ($104 million, $40 million budget). Water Horse is an especially odd one to end on because it’s the rare Revolution project where another production company has more of the authorial voice. That production company is Walden Media, who, starting with Holes in 2003, built a cottage industry out of children’s book adaptations. Their track record was mixed (they even broke Revolution and Gigli‘s record of the biggest drop in theater screens from one weekend to another with Hoot, and then again with The Seeker: The Dark is Rising), but by the time Water Horse was made, they were hot off the massive success of the first Chronicles of Narnia and had just made $137 million on the movie where AnnaSophia Robb drowns in a creek. Accordingly, Water Horse (based on a book from the author of Babe) was marketed as coming “from Walden Media who brought you The Chronicles of Narnia” and not “from those Revolution Studios idiots who brought you The Master of Disguise“.

More about that marketing. The trailer for The Water Horse makes it look like wall-to-wall hijinks, about a burping sea monster who lives in a toilet and ruins dinner parties. With this being my only expectation for Water Horse, I was surprised to learn that it’s far more wistful than that, more a parable about the destructiveness of World War II than a movie where a sea monster is chased by a bulldog (the trailer shows a scene where the full-grown sea monster scares off the bulldog, but in the movie it’s strongly implied he eats the dog). The war has already decimated the MacMorrow family by the movie’s start, the mother (Emily Watson) was widowed when the soldier father was lost at sea and young Angus (who grows up to be Brian Cox in the present-day framing device) has deluded himself into believing that his dad’s still coming home. Angus’s discovery of the water horse (who he names Crusoe) coincides with the war effort invading his home, via a battalion of British soldiers setting up camp in the backyard. And that’s before the handyman (Ben Chaplin) with literal scars from the war shows up. While Crusoe does get into some mischief around the house, that whimsy is juxtaposed against the sadness that hangs over Water Horse rather than being the whole thing. It’s funny when the town drunk spots Crusoe and stages the famous Loch Ness Monster photo (in this universe, the photo is still a fake), but the fun fades away by the time combat comes to this small village and soldiers are bombing the hell out of the Loch, first as empty pageantry and then as an attack against poor Crusoe. David Morrissey’s hard-ass captain is the only soldier with personality beyond the weapon he uses to hurt others, he gets a minor redemption arc that’s a little easy but still barely interferes with the movie’s cynicism about the military. Kind souls like Angus’s dad or Chaplin aren’t cut out for this kind of brutality (Chaplin refuses to answer Angus’s questions about whether he shot down planes during the war because he knows that’s nothing to be proud of) and the ones who are cut out for it are trigger-happy brutes, going to the most beautiful places on Earth and hoping there’s German submarines they can shoot at there. The boy-and-his-monster plot is a simple but effective counterpoint to all this violence, emphasizing the wonder of the natural world and the value of friendship over blind hatred. Obvious lessons but ones that parents need just as much as their kids.

One of the biggest surprises of this series was Peter Pan, a shockingly intelligent take on its source material and all its deeper meanings, as well as a rousing adventure that kids and adults can get wrapped up in. Water Horse isn’t quite that good but it’s in that same league, it understands that kids aren’t nearly as stupid as the movies targeted at them often are. Many movies allegedly pitched at adults wouldn’t be brave enough to end the way this movie does, a “here we go again!” happy ending that becomes something much more bittersweet when you consider what it’s calling back to (a throwaway bit of water horse mythology mentioned once and never repeated), all without a single line of dialogue or even a music cue to tell you how to feel about it. If this was really the final note of the Revolution experiment, it’d be an uncharacteristically subtle, thoughtful one. So of course it wasn’t the end.

The Aftermath

For just under a decade, Revolution laid dormant. They were technically still around, their TV unit (whose only projects while the movie studio was still functioning were three American Girl TV movies and an Oliver Platt courtroom drama cancelled after three episodes) produced a few TV adaptations of their movies, including the Charlie Sheen Anger Management show with its famous 90-episode second season. Roth, meanwhile, went back to producing full-time, stumbling upon the profitable racket of producing slightly darker reboots of old Disney movies; the Burton Alice in Wonderland, Maleficent, Snow White and the Huntsman, those are all his. In 2014, Roth sold Revolution for $250 million to Fortress Investment Group, finally severing the company from its creator and sole remaining original employee. It would sure seem like that’s the end of the road for Revolution, but Roth had one more trick up his sleeve.

2017

In 2006, the year after xXx: State of the Union bombed, Vin Diesel set up that he’d be returning to that other franchise he left behind after one movie with a cameo at the end of The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift. Diesel’s proper return, Fast & Furious in 2009, was a surprise smash considering the tepid response to Tokyo Drift and Diesel’s own box office cold streak (his most recent film before F&F was the Mathieu Kassovitz disaster Babylon A.D.). Then Fast Five was an even bigger hit, then Fast & Furious 6 was even bigger than that, and then Furious 7 turned the franchise into a billion-dollar juggernaut. Diesel had orchestrated a remarkable comeback for both himself and this franchise. After Furious 7‘s release in 2015, he was red-hot and could do whatever he wanted. What he wanted was to rejoin the xXx franchise like he did with Fast & Furious. And so, with Revolution still holding the rights to the xXx franchise, in 2017 we got one last Revolution production: xXx: Return of Xander Cage ($346.1 million, $85 million budget). This wasn’t just the zombie Revolution either, as Joe Roth returned to produce it (though Sony wasn’t involved, letting the rights to the series go to Paramount). And so Roth and his company’s stories end, improbably, with a hit.

I have no love for the first xXx, a toxic piece of shit made by one of the worst people alive, and I especially did not like Xander Cage, a gross meathead who could only be a lame middle-aged man’s conception of an “extreme” action hero. State of the Union has many problems but I thought Ice Cube’s Darius Stone was a pretty fun hero who I’d be happy to see more of (the general public did not agree with me on this). So Xander returning wasn’t much of a selling point for me, but with Rob Cohen no longer directing, I had hope that maybe Xander wouldn’t be such a self-serious lech this time. Hope that was immediately proven correct by Xander’s entrance, where he uses his extreme sports expertise to bring cable to a Dominican village in time for a soccer match. This Xander is much more in Vin Diesel’s wheelhouse, a benevolently goofy anti-authority folk hero who loves to skateboard; he still likes to fuck insanely hot women, but in a gentlemanly way this time. He even gets to be a team player now, the series following Fast & Furious‘s lead of surrounding Diesel with a group of big personalities: Donnie Yen, Tony Jaa, a lesbian sharpshooter played by Ruby Rose, a belligerent British getaway driver, and a guy whose skill is that he’s an amazing DJ (it comes in handy), among others. The shift to a team versus a rugged individual means it’s no longer the first movie’s attempt to supplant James Bond, it’s now more like a dumb-guy version of a Mission: Impossible movie, and that’s not bad at all.

If the proper Mission: Impossible movies can sometimes get bogged down in the plot between the stunt shows, this has serious peaks and valleys between its best moments and its merely functional ones. It’s got a big nothing of a government conspiracy plot, when Toni Collette shows up as a contemptuous CIA agent she might as well be wearing a “Hi! I’m the secret villain” nametag. But it’s also got some genuinely crazy stunt sequences, a few rendered in less-than-convincing CGI (the climactic money shot even makes its absurd cartooniness a virtue) but mostly real and surprisingly visceral for a PG-13 blockbuster, like Donnie Yen owning goons with the heaviest-looking punches you’ve ever seen or Yen and Diesel having a fight scene in the middle of a busy road. Neither xXx before it had particularly strong action but director D.J. Caruso (Hollywood conservative and very good The Shield director) fits in some incredibly impressive, clever setpieces, complete with overcranked digital cinematography that may earn a comparison to late Michael Mann. The one thing State of the Union has over this is its strong sense of humor, which this initially retains until it gets too bogged down in po-faced government intrigue. But even if its one-liners get more canned as the movie goes on, it still offers up two bravura set-up and payoff quips, where the initial lines rings in your ear but you don’t suspect they’ll come back until the moment they do. These are the kind of little action conventions that, if done right, can separate passable trash from an honest to god good time. These are what Revolution was bad enough at, across all genres, that most of their work couldn’t even rise to the passable trash level.

What Have We Learned?

In a 2006 interview with blackfilm.com, Joe Roth tells a story about his days as president of Fox. In 1990, he got a call from George Lucas congratulating him on having a big hit on his hands. He had seen the trailer for Home Alone in a theater and could tell audiences were gonna love it. When Roth asked how he could tell, Lucas replied “The movie business is binary. The lights are either on or off; and if the light’s on, you can’t get it off. If the light’s off, there’s nothing you can do to get it on.” As Lucas often is when talking about film the industry, he’s right. Trying to predict what audiences will respond to and what they won’t is a crapshoot, you can try chasing trends or relying on familiar stars, but the ultimate power is in the audience’s hands and you don’t know shit about what they think until your movie is playing in front of them. Revolution made a lot of shit movies, but plenty of shit movies still get audiences by the droves. Revolution’s problem was ultimately that Joe Roth’s creative ideas at this time were mostly in direct opposition to what audiences wanted to see. The light was off and nobody was home.

I thank you all for taking this journey with me through the dregs of turn-of-the-millennium mediocrity, I hope it made you laugh and maybe even strengthened your understanding of studio filmmaking after the towers fell but before the superheroes took over. It’s an ugly time for culture, but with just enough diamonds in the rough to make you wish the system was still in place to make them on a major-studio level. Joe Roth may have had terrible studio-head instincts, but when his successors in the business are idiot theme-park directors with no knowledge of movies, he doesn’t seem quite as bad. At least until I remember Tomcats.

The Final Ranking

The Worst of the Worst

48. Daddy Day Camp. More like Cuba *Bad*ing Jr.!

47. Tomcats. Watching this at the start of this series really made me worry that there’d be a whole bunch of movies as bad or worse than it, I’m very glad there was only the one.

The Pits

46. Zoom. When’s Chris Evans gonna take on this iconic Tim Allen role?

45. The Fog. I cannot emphasize strongly enough that there is a scene near the end of this where a man appears to be stop-drop-and-rolling away from an evil ghost.

44. Radio. More like Cuba *Bad*ing Jr.!

43. xXx. This movie fucking sucks but my dislike of it is nothing compared to my firm belief that the world would be measurably improved if someone were to murder Rob Cohen.

42. Perfect Stranger. The worst thing Scientology has ever led to is this Giovanni Ribisi performance.

41. Gigli. As Nathan Rabin and Orlando Bloom have preached, a fiasco is a much more noble, interesting thing than a failure, which is why this places above the previous insulting mediocrities despite being exactly as bad as everyone says it is. Plus, it somehow led to the only feel-good celebrity story of this year.

The Worthless

40. Are We Done Yet?. Movies shouldn’t review themselves like this.

39. Tears of the Sun. All love to Bruce Willis, frequently a tremendous actor, but he really beefed it in this one.

38. Darkness Falls. This has to have the lamest token PG-13 “fuck” there’s ever been.

37. An Unfinished Life. I’m still mad about how I was convinced this movie was going to end with Damian Lewis getting mauled by a bear and it doesn’t.

36. Are We There Yet?. No, we’re not.

The Regular Bad

35. Little Man. Peaks at David Alan Grier’s appearance and he comes in early.

34. The Benchwarmers. I still think back on “I am 12” and laugh, that’s more than can be said for almost anything below this.

33. Next. Make The Card Counter with Cage’s character in this and maybe you’ve got something.

The Bad+

32. Little Black Book. We really did so badly by Brittany Murphy.

31. America’s Sweethearts. Fuck it, they should let Billy Crystal host the Oscars again.

30. Freedomland. Julianne Moore should have all copies of this buried in the desert like the E.T. Atari game.

29. The Forgotten. This is actually about grief if you think about it.

28. The Master of Disguise. As much as I did not enjoy watching this, its existence is maybe the funniest to think about of any movie here, which gets it more credit than any of the other bad movies in this group. If you haven’t already, I highly recommend reading Brian Feldman’s excellent, melancholy reporting on the infamous “Turtle Club scene shot on 9/11” rumor. I also recommend watching this:

27. Rent. This places much higher if you measure these movies in cups of coffee.

26. Hollywood Homicide. It’s just a shame they appended a terrific half-hour of action to the end of 90 minutes of naptime.

The Almost-There

25. xXx: State of the Union. Someday, the vulgar auteurists will embrace Lee Tamahori, and maybe they’ll be a little right to do so.

24. Across the Universe. Stream The Glorias for a terrific Alicia Vikander performance (and a passable Julianne Moore one) and the vague sense that it’s Julie Taymor’s version of The Irishman.

The Alright

23. The Animal. There’s a scene in Bruno Dumont’s excellent France (stream on Criterion Channel for an even better than terrific Lea Seydoux performance) that I’m convinced is an homage to a similar scene in this.

22. The New Guy. Shout out to Lyle Lovett.

21. Click. If you use “Linger” as a recurring emotional device and then climax with “Ultraviolet (Light My Way)” blasting on the soundtrack, you’re gonna move me eventually, I’m not made of stone.

20. Maid in Manhattan. Everything that’s happened with Jennifer Lopez this year is very nice, she’s a great presence even in something this disposable.

19. Mona Lisa Smile. Kirsten Dunst excelled like almost no other actor at high-school movies, this is her only college movie and the same spark isn’t there.

18. White Chicks. Seeing the trailer for this at the time was the first time I heard “A Thousand Miles” and this movie is still the first thing I think about when I hear that song.

17. Christmas with the Kranks. Chris Evans would actually be really bad as Luther Krank.

The Pretty Good

16. Anger Management. Spielberg wishes he could’ve done this much with “I Feel Pretty”.

14. xXx: Return of Xander Cage. This has a very solid token PG-13 “fuck”.

13. Stealing Harvard. In hindsight, very obvious as a movie directed by a Kid in the Hall.

12. Man of the House. I’m sitting here waiting for the Kelli Garneraissance to start.

The Pretty Darn Good

11. Hellboy. I can underrate this relative to the more exciting or more thoughtful Del Toro movies, or I can just be thankful for its rock-solid action trash and for it not being Nightmare Alley.

10. The One. This may slowly be developing a cult following and I’m 100% behind it, it’s a testament to how good trash can be with the right people behind it.

9. Rocky Balboa. Very touching, except for the punching (but there’s a lot of punching).

8. The Water Horse. Very touching, except for the burping (but there’s only one scene of burping).

7. Black Hawk Down. Ridley Scott can make a two-and-a-half-hour (or more!) slog through the worst of humanity really sing. Sometimes.

6. 13 Going on 30. Movies don’t let Andy Serkis do the Thriller dance anymore and that’s why they’re in the toilet.

5. The Missing. Ron Howard may have settled into mostly being a boring substitute-prestige stooge, but sometimes he’ll really show up to play.

The Great

4. The Brothers Solomon. *Wayne Coyne voice* Ya ya ya ya ya ya ya ya

3. Peter Pan. I’m sure the David Lowery Peter Pan movie will be good, but I guarantee it will not be as good as this.

2. The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio. Nobody besides Todd Haynes is giving Julianne Moore parts this rich.

The Greatest

1. Punch-Drunk Love. That’s that.