Welcome to Pictures of a Revolution, a year-by-year study of the output of Revolution Studios. This year, Adam Sandler loses track of time and Julianne Moore loses track of another goddamn kid.

The Prelude

This is the year Revolution officially dies. Their distribution deal with Sony was not extended past its expiration in 2007, not after their 2005 had two costly bombs and one $100-million-loss catastrophe. 2006 would be the last year Revolution had films in active production, next year they’d have what they shot this year and that’s it. With nothing on the line except the chance to not horribly embarrass themselves, they rose to the occasion and only embarrassed themselves a little.

The Films

I’ve read many depressing profiles of Joe Roth in the process of doing this series, but this L.A. Times piece from May 2005 may take the cake as the saddest of them all. After years of “we’ll turn it around next year”, Roth seems genuinely defeated, approaching Revolution’s failures and missed opportunities with unexpected candidness (he says that Revolution had the opportunity to produce Sideways but passed because Roth felt “we just weren’t geared to make that kind of movie”). He’s particularly haunted by his own decision to make Christmas With the Kranks, which he calls “a dismissible piece of lowbrow commercial entertainment” that he couldn’t even get his close friends to watch. Kranks and America’s Sweethearts were both safe-territory broad comedies with big stars, made only because he wanted Revolution to be successful and not because he had any personal investment in them. And so, at his company’s darkest hour, Roth realized he had to make a movie he really wanted to make lest the missed opportunity eat away at him the rest of his life. This is why he decided to make Freedomland ($14.7 million, $30 million budget), a grim crime drama based on a Richard Price novel. Roth was drawn both to the material’s political dimension (it’s at least partly about the police occupation of a Black housing project) and to its story of a missing child, which the profile ties to the loss of his firstborn child to sudden infant death syndrome. Obviously, I feel for the guy and am glad he got to process that grief while making this (to quoth Phoebe Bridgers, we hate Are We There Yet? but it’s sad that his baby died), but I must report that Freedomland was not the cathartic creative or personal victory Roth was hoping for. It was originally scheduled for an end-of-2005 Oscar qualifying run, but that was scrapped in favor of an unpromising February release date. It got bad reviews and made little money, and Roth has not directed a movie since.

I don’t wish to damn Roth with the crime of not being Spike Lee, since only Spike Lee is or should be Spike Lee. But it’s still illustrative to compare Freedomland to Lee’s adaptation of another Richard Price novel, Clockers. Clockers isn’t a subtle movie in its critique of both law enforcement and drug runners preying on and taking advantage of young Black men, but it develops such a strong, specific sense of place, both in the easy rapport of its neighborhood kids and the horrifyingly callous small-talk of its cops, that it still feels like a well-rounded portrait rather than a polemic. The same cannot be said for Freedomland, which isn’t subtle and isn’t insightful either. Roth doesn’t invest nearly enough in developing any sense of community amongst the residents of the housing project, even with great actors like Clarke Peters and Aunjanue Ellis playing them, they’re mostly just sad or angry Black faces for Roth to cut to when emphasizing that police overreach is bad. By the time riots are breaking out, Roth has taken so little care to show the escalation leading to that point that they seem like a totally arbitrary development. And the treatment of the riots is some real mush-brain liberal shit, “can’t we all just get along?” platitudes and score that sounds like dollar-store “An Ending (Ascent)”. How does this all connect back to the simple matter of a missing child? I don’t know and I don’t get the sense that Roth knows either, it’s not quite this bad but I was reminded of Suburbicon‘s inept combination of crime thriller and serious issues drama to no larger point besides “we live in a society”.

So far in this series, I’ve had nothing but nice things to say about Julianne Moore. The Forgotten is junk but she’s terrific in it and The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio is one of her best, most unsung performances. Alas, that run of quality ends here, because Moore is ruinous in Freedomland. I kept being reminded of her performance in Magnolia, a movie already operating far outside of subtlety that she still finds a way to do too much in. I don’t hate her in Magnolia like some do, probably because Paul Thomas Anderson wisely balances her out with an otherwise uniformly terrific cast. Joe Roth may have worked with Paul Thomas Anderson, but he is no Paul Thomas Anderson. He directs Moore to a much worse performance and makes her the center of attention, where she becomes a black hole the movie can’t escape from. If you love seeing Moore’s open-mouth cry face, she’s doing that in practically every scene in this, all while she slurs her words in a baffling New Jersey(?) accent. It’s a grotesque, oh-so-actorly pantomime of grief, especially disappointing for how rich her portrayal of a similarly bereaved mother in The Forgotten is. While Moore is busy playing catatonic, Ron Eldard tries a different kind of unnecessary intensity by bulldozing into all of his scenes as Moore’s hothead racist brother. He’s not in it that much, but when all his scenes quickly devolve into a screaming match, a fist fight, or both, his presence just becomes another layer of aggravating noise on a frequently histrionic movie. It’s a shame because this movie has two terrific performances that deserve better company. Samuel L. Jackson is one of the most charismatic actors alive and for its many faults, Freedomland is a strong showcase for everything he does well; he gets to play sensitive, a wry smartass, and a furious crusader against the system, plus he calls someone a “brotherfucker”. He almost singlehandedly drags the movie to watchability, but the actor who actually manages to make the movie good for a little bit is Edie Falco, playing the leader of a group of mothers who search for missing children. Her section of the movie basically amounts to a 10-minute tangent in the middle, and it’s the only part that successfully conveys Price’s interest in the precarious lines between individuals and institutions. The Falco character lost her own child years before, but her performance is driven mostly by ingenious calculation rather than lasting sadness. The best scene in the movie is a Falco monologue about her child’s killer that slowly and subtly transforms, via Falco repeating a mantra (“just shake your head yes or no”), into Falco grinding Moore down to get a confession. This is real-deal great acting, changing the tenor and meaning of a scene while seeming to do nothing. Shame that Roth’s conception of great acting seems to be sub-“IS THAT MY DAUGHTA IN THERE” outbursts.

Hey, it’s been awhile since we’ve heard from Adam Sandler, what’s he been up to? Mostly succeeding while Revolution was failing. Both 50 First Dates and The Longest Yard came within spitting distance of grossing $200 million worldwide, and while Spanglish was a bomb, nobody held it against Sandler for trying something new. But while Sandler was as big as he ever would be, the novelty of Sandler producing vehicles for his buddies was really starting to wear thin. They should generally count on at least being profitable until Dickie Roberts: Former Child Star in 2003, which still stands as the lowest-grossing #1 movie of any weekend before the pandemic ($6.7 million, barely topping the second weekend of Jeepers Creepers II). 2005 saw Deuce Bigalow: European Gigolo gross half the numbers of its predecessor, and Grandma’s Boy in 2006 just barely recouped its $5 million budget. But the mistake those movies made was only centering on one Happy Madison repertory player. Why not have a few of them team up? This is the logic that led The Benchwarmers ($65 million, $33 million budget) to comparatively healthy numbers and a strong afterlife on home video (Wikipedia claims, sans citation, that it’s developed a cult following “especially amongst baseball fans”).

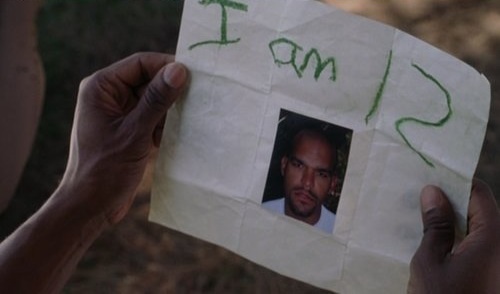

There are so many bad comedies out there with not a single good joke to show for themselves (some of them may have even been covered on this series already). Benchwarmers is a bad comedy with one sublime joke. At one point, in a last-ditch effort to stop the momentum of the titular rag-tag baseball team (three adults playing against Little League teams to stand up against them bullying and not admitting the weaker kids), a rival team hires an obviously full-grown man to play against them. When asked to produce evidence that he’s a child and able to play on a Little League team, the man produces what he claims is his birth certificate:

Funny! Director Dennis Dugan and writers Allen Covert and Nick Swardson can sleep well knowing that they created a great sight gag. Unfortunately, they also have the rest of the movie to answer for.

Generally, the Sandlerless Happy Madison movies do a good job of being built around the specific talents and personalities of their stars rather than around the style of their producer. Whatever you think of Joe Dirt, you can’t imagine Sandler stepping in and playing Joe Dirt, it wouldn’t work for a number of reasons. But Benchwarmers is the rare case where not only could Sandler be the lead, Sandler should be the lead. It’s directly in his wheelhouse: he’d proven twice before that he works great in silly sports comedies (Longest Yard excepted because it’s not silly enough), it would involve him antagonizing children just like in Billy Madison, and the main character is written as having struggled with past rage issues. It seems so perfect for Sandler that I wonder if it was written for him before he turned his attention elsewhere. I certainly don’t buy that it was written to serve the abilities of Rob Schneider. Schneider seems to fundamentally misunderstand how to play this character, where the subtext of all his actions is a driving anger that made him a terrifying bully as a younger man. Schneider instead plays him so even-keeled from beginning to end that I get no sense he was ever anything but milquetoast. I don’t even buy his performance as him having atoned for his sins, he just seems like a normal, kinda boring guy from beginning to end. If we’re to judge this performance on how well he conveys that normality, he’s perfectly competent in the part, but he doesn’t have the Sandler magic to make an average joe sweet and compelling. And without a strong enough personality to bounce off of, Schneider’s teammates are left adrift. David Spade is similarly miscast, playing a confused mishmash of his usual smarmy asshole persona and the good-natured doofus he played (surprisingly convincingly) in Joe Dirt. Jon Heder gets the easy assignment of playing the socially-maladjusted fool and coasts to being the default MVP of the trio, but he doesn’t have the spark that enlivens a truly great idiot performance. It’s easy to see why the Jon Heder leading man experiment ended so soon after this.

Sandler starring in The Benchwarmers fixes one problem with it but leaves a larger problem unaddressed, which is that it’s not very funny. I’d seen and been amused by the trailer many times in the last 15 years, but I didn’t realize until sitting down to watch this that every funny joke in the movie except “I am 12” is in the trailer, and one of them is literally only funny because of how the trailer plusses it (in the trailer, when Heder holds a hot potato too long, he screams hysterically, but in the movie he just makes wacky faces). Almost any scene not crammed into those two minutes is a laugh desert despite the presence of typically reliable Happy Madison crew members like Tim Meadows, Terry Crews, and Jon Lovitz. There’s an inexcusable amount of time spent on “jokes” that are just nerd jerk-off fantasies, where Lovitz’s billionaire character (financing the Benchwarmers as revenge for his son getting picked on) spends his riches on elaborate Knight Rider and Star Wars replicas. Otherwise, the jokes are just unfunny in standard, boring ways, it’s hard to be offended by the frequent homophobic jokes when they’re just lazy more than anything. At least this gave us #OnePerfectShot.

In Revolution’s original 47-movie run, only two (2) of their movies crossed $200 million in worldwide box office. xXx was the first, and Click ($240.7 million, $82.5 million budget) was the second. As I said above, Adam Sandler was a very reliable box office performer around this time, but Click topped all his recent hits by almost $50 million, on the back of an irresistible high-concept premise everybody can relate to and a slightly more serious approach that attracted more than Sandler’s usual audience of teenage boys. Critics mostly rolled their eyes at Click‘s sappiness but it worked on audiences and it even got an Oscar nomination for its makeup, to date the only Oscar attention afforded to any Sandler movie (including the auteur ones).

Click is an undeniably important work in the Sandler oeuvre. It’s a first attempt at reconciling the dramatic heft of Punch-Drunk Love with his usual goofy sensibility, which eventually leads to such great mature/immature works as Sandy Wexler and The Week Of. And as noted in Vulture’s excellent ranking of every Adam Sandler movie, it serves as the dividing line in Sandler’s filmography between the movies where he predominantly plays man-children and the ones where he mostly plays dads (and regular dads, not man-children forced to be dads). Unfortunately, being the first go at this new formula puts Click in the tricky position of not being as entertaining as many of the Sandlers that come both before and after it. Compared to his last Revolution movie Anger Management, which wouldn’t even place in my top ten of Sandler movies, the laughs here seem a lot more strained and sour. You always have to take the good with the bad when watching a Happy Madison, but this makes that a lot harder with just how cruel so many of its jokes are, starting with Rob Schneider in brownface within the first five minutes and going onto jokes about Japanese businessmen, sexual harassment, and Rachel Dratch as a trans man (that unfortunately makes Sandler 1-for-3 in this series for making movies without sudden transphobic jokes, thank god for woke king PTA). Even the typical Sandler slapstick lands a lot less often than it should, like he’s going through the motions with the old stuff while being more invested in the new angles. It’s an interesting counterpoint to Punch-Drunk Love, a similar transitionary work that contains the best of both worlds while this is a more typical middle work, where the kinks are getting worked out while the movie’s unfolding.

If Click is deficient as a comedy, it’s shockingly effective as a tearjerking drama. The critics were right that this is pure sap, but if it feels like sap is coming from an honest place, it can land just as hard as any more “respectable” means of producing tears from an audience. Given that Sandler has proven time and again how loyal he is to both his professional and personal families (Sandy Wexler is all about show business as one big found family), I have no doubt he believes wholeheartedly in this movie’s “family comes first” messaging, and it’s moving to see somebody so passionate about such a simple message. Sandler shot this after he had recently lost his father, a time in any person’s life when they realize just how fleeting one’s time with their family can be; you can see real pain, not movie pain, in the scene where Sandler’s character futilely tries to elongate the last moment he ever spent with his father. You can dismiss that and this movie as cheap sentimentality, but there’s so much earnest feeling there that critics either didn’t pick up on or refused to pick up on in Sandler’s work until more name-brand auteurs started working with him (“Genius Girl” from Meyerowitz Stories, one of the best scenes of last decade, has much more in common with this movie than it has with any other Noah Baumbach movie). Sandler’s the furthest thing from a perfect artist (again, I don’t think Click is very funny at all), but now that I’ve begun going deep on him, I feel bad for buying the company line on him just making cynical, lazy movies to cash a check. Even his very worst work has a baseline sincerity to it that makes it clear why people loved and still love him, the man believes what he’s selling whether it’s Uncut Gems or it’s Click.

Of the Wayans brothers’ two Revolution projects, White Chicks gets both the most vitriol and the most defenses, its (undeserved) status as an all-time low in comedy further emboldening the people who enjoy its high-concept insanity. Little Man ($104 million, $64 million budget), meanwhile, got the same bad reviews without the benefit of punchline status to bring defenders out of the woodwork. Albert Brooks wasn’t singing Little Man‘s praises on that year’s Oscars, ironically or unironically.

Perhaps a key difference in Little Man‘s reception versus White Chicks‘ is how both movies go about their high concepts. The design of the white chicks is so bizarre and uncanny that it provides either an instant laugh or immediate terror, while the digital trickery that goes into putting Marlon Wayans’ face on a little person’s body just looks bad in more “normal” ways, the movement isn’t right and the head looks like it’s shot at a different frame rate than the rest of the body but there’s no reason to be scared of that. Plus, White Chicks‘ plot means that every scene has the charge of “how is nobody seeing through these disguises?”, but the effects in Little Man aren’t supposed to convince the characters in the movie, they’re supposed to convince the audience and they don’t. One is a “failure” that easily becomes a strength if you find its implications funny, the other is just a failure. And as hack it is to say that practical effects have more “character” than digital effects, there is something to that idea in this case, where the singular flaws of the White Chicks makeup get smoothed out to the more regular occurrence of bad CGI face replacement.

The relative lack of personality in Little Man‘s effects extends to the rest of the movie too, this ultimately doesn’t have White Chicks‘ legacy because it just isn’t as funny or interesting as White Chicks. As with White Chicks, the plot is a total nonentity and the gags are very hit-or-miss (the best one is watching Shawn Wayans get whacked in the nuts by three separate children’s toys), but watching these two movies near each other is a reminder of just how much value a few very committed comedic actors can provide a dumb comedy. Little Man has a solid bench of supporting actors but none of them have the spark that Busy Philipps and Terry Crews have in White Chicks, the ability to find genius within stock material. The actors here who even come close to that are one-scene players like Molly Shannon (as a soccer mom with frightening multitasking abilities) and David Alan Grier (as a very pushy keytar player), they provide brief bursts of energy and then they’re gone. The Wayanses don’t fill this void with much, mostly a lot of jokes about how horny Marlon Wayans is even though he’s a “baby,” which start at creepy and unfunny and only get creepier and unfunnier the more the movie returns to that well (by the movie’s end, Marlon has committed multiple sexual assaults against multiple women). And the movie’s few scenes conveying its indifferent “family is important” message really put into focus what Click does right with its emotional scenes, letting them play out like they’re just as important as the comedy (because they are) rather than the Wayanses throwing on some sad strings every 10 scenes as a break between the goofiness.

The movie star career of Tim Allen was built on the twin pillars of the Santa Clause and Toy Story franchises. Those movies were all big hits, but Allen on his own was a much less reliable performer, topping out at mild successes like Christmas With the Kranks and The Shaggy Dog and often making outright bombs like Joe Somebody and For Richer or Poorer (even the much-loved Galaxy Quest wasn’t a big hit on release). 2006 was the year of the final Santa Clause film, an unofficial end to Allen’s live-action acting career. A much more decisive nail in the coffin that year was the release of Zoom ($12.5 million, $75.6 million budget), the biggest flop of his career. After Wild Hogs the next year (where Allen joined forces with three other actors on box-office losing streaks to make a massive hit), Allen would never again lead a studio comedy.

Like so many Revolution projects, Zoom was an unpromising idea that Roth and Co. threw an obscene amount of money at anyway (they seemed particularly embarrassed by this budget, since the “official” budget was listed for years as $35 million; the effects look cheap even at that price). Unlike those other projects, Zoom was so unpromising that it actually got Revolution sued. In 2005, Fox and Marvel sued Revolution and Sony over Zoom, claiming that its tale of superpowered teens and children taught to harness their abilities in a special school was infringing on X-Men, and that Zoom‘s release date being two weeks before X-Men: The Last Stand was a conscious attempt to steal business away from Fox. The lawsuit was dropped after Sony agreed to a few conditions: push Zoom to an August release far away from Last Stand and make a few alterations to keep Zoom at a PG rather than Last Stand‘s PG-13. But that last change only made Zoom seem like a copycat of a different superhero movie of the time: Sky High, Disney’s family-friendly superhero comedy released the year before. Sky High is the Gallant to Zoom‘s Goofus; it actually cost $35 million, made $86 million, got good reviews, and stars Kurt Russell, Mary Elizabeth Winstead, and multiple members of Kids in the Hall, rather than Tim Allen, Kate Mara, and Chevy Chase. But Zoom does outdo Sky High in one area, which is sheer number of Smash Mouth songs. Smash Mouth mania in studio comedies had died out soon after the one-two punch of Shrek and the ending of Rat Race in 2001 (even Shrek 2 in 2004 knew better than to include a single one of their songs) but you wouldn’t know that watching Zoom, made five years later and featuring so many Smash Mouth songs (including a cover of “Under Pressure”) that there’s a separate “Songs by Smash Mouth” card in the opening credits. Sky High, meanwhile, had moved onto the greener pastures of Bowling For Soup.

Zoom is unfunny and dumb in all the ways bad 2000s kids movies are, with a lot of lame slapstick (Courteney Cox’s scientist character will fall over whenever the movie can’t figure out how to end a scene) and some unusually shoddy bodily-function gags (a gag with a child whose power is superhuman gas can’t even use a fart sound effect loud enough to be that out of the ordinary, another gag with Tim Allen belching has some of the worst ADR I’ve seen in a major movie). If Zoom was merely unfunny and dumb, that would be one thing. But Zoom is also extremely unpleasant, largely on the back of a Tim Allen performance that crosses the line between snark and outright cruelty. The conception of the Allen character, a burnt-out former superhero tasked with training a new generation of heroes, is that he’s a cynic with a heart of gold, but he’s just a toxic piece of shit. It’s not fun to watch Allen belittle children for the crime of being excited about having superpowers, harass Cox both sexually and verbally (this movie’s idea of a fun quip is having Allen ask Cox if she’s bipolar), and make a lot of gay jokes about Rip Torn. I talked about Allen playing an asshole in Christmas With the Kranks and I have to give Joe Roth a little credit for directing Allen to play an actually funny kind of asshole. Zoom director Peter Hewitt (who once upon a time made Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey) can only make Allen the grating, unfunny asshole he is in real life, and none of the movie’s goopy sentimentality (including a montage set to Five For Fighting’s “Superman” and a slow dance set to Enrique Iglesias’ “Hero”, are we sure this movie wasn’t filmed in 2002 and held back?) can make me think any better of this prick. Even when he has to play the hero at the end of the movie, ostensibly fighting to save the life of his brother, he can’t drop the lame smartass routine for one second. Allen’s half-assed, ADR’d-in delivery of “Must… save… Connor!” to let us know that he actually cares about his brother is maybe the only laugh in the entire movie.

MGM’s recent sale to Amazon is just the latest part of the decades-long game of hot-potato being played with MGM’s film library. In 2004, it landed in Sony’s hands, who wanted MGM catalog titles to promote the then-forthcoming Blu-Ray format. The Sony deal only lasted two years before the library was sold again to Fox, but it lasted just long enough that two of Sony’s late-2006 blockbusters were both from MGM properties. One was Casino Royale, which I think did okay. The other was the Revolution-coproduced Rocky Balboa ($156.2 million, $24 million budget). Creed later got more acclaim and made even more money but it shouldn’t be forgotten that Rocky Balboa was seen as a massive turnaround of the franchise, finally getting it back to something like reality after the absurdity of the previous sequels.

The first half or so of Rocky Balboa is kind of incredible. On paper it shouldn’t be more than crass nostalgia-baiting, scene after scene of Rocky recounting his greatest hits to anyone who’ll listen. But it never feels like Stallone-the-director is going for cheap recognition from the audience, all these stories are there because they’re a perfect reflection of the melancholy of being old Rocky Balboa, doomed to view his life in terms of the glory days that have now long passed. He’s told these stories so many times that his audiences can dutifully finish his sentences for him, and he gets asked to pose for so many photos that he has the fist placement of his photo partners down to a science. He reveals the inherent complacency of nostalgia, sustaining himself on memories of the past when he could be finding a new way forward instead (Rocky’s often framed against the once-beautiful but now crumbling architecture of his beloved Philadelphia, the comparison is clear). But the past can be what offers that new way forward, as it does when Rocky strikes up a platonic friendship with Marie, last seen as a kid in the first Rocky. Their scenes together are sweet without being sappy, just two worn-down adults doing their best to help each other improve. All this happens before Rocky even has the inkling to start fighting again (at the 40-minute mark), and it sets the stage for what could be a terrific boxing-free Rocky movie.

But of course, there’s no chance of a boxing-free Rocky movie getting made without fans screaming bloody murder, so Rocky has to move forward with his life by getting back in the ring (via the shaky justification of Rocky being inspired to start fighting again by an ESPN computer simulation). This isn’t to say the movie nosedives once it becomes a more traditional Rocky movie; there’s good material with Rocky’s opponent Mason Dixon struggling with how to go forward with his own legacy (to the point I wish there was a lot more of that), and Stallone makes the very inspired decision to shoot the climactic fight almost entirely with digital ringside cameras, the shock of the new intruding on the movie’s otherwise 70s-grainy aesthetic. But the expected training montages and triumphant “Gonna Fly Now” drops feel a little incongruous with the wistful tone the movie had set up to that point, plus we start spending less time with Marie and more time with Milo Ventimiglia as Rocky’s son, who simply doesn’t have enough charisma to play opposite Stallone (acting at the top of his game here) and not feel like he’s out of his weight class. And even the pay-per-view aesthetic of that final fight eventually gives way to some baffling, “I just saw Sin City“-ass color-correction gimmicks. Stallone was so close to successfully staying out of his own way the whole movie and he couldn’t quite manage it.

The Conclusion

If you’ll indulge me in a bit of psychoanalysis, Rocky Balboa‘s placement near the end of the Revolution experiment makes me wonder how much Joe Roth saw himself in this story of a once-respected old-timer sadly reflecting on better times. Did Roth believe that with what little time Revolution had left, he too could orchestrate a miracle comeback? I hope I’m not ruining any of the next article’s surprises when I say that no, he did not orchestrate any such comeback. I suppose this year could’ve been a building block for a better future if the ending wasn’t a foregone conclusion, but even here we still see the bad creative instincts and bloated budgets that brought Revolution to the point of collapse in the first place. Roth is just not very good at this, he probably shouldn’t have tried it in the first place.

The Ranking (so far)

- Punch-Drunk Love

- The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio

- Peter Pan

- Black Hawk Down

- The Missing

- Rocky Balboa

- 13 Going on 30

- The One

- Hellboy

- Man of the House

- Stealing Harvard

- Anger Management

- Mona Lisa Smile

- Daddy Day Care

- The New Guy

- Maid in Manhattan

- Christmas With the Kranks

- Click

- The Animal

- xXx: State of the Union

- White Chicks

- Hollywood Homicide

- Little Man

- Rent

- America’s Sweethearts

- Little Black Book

- Freedomland

- The Forgotten

- The Master of Disguise

- The Benchwarmers

- An Unfinished Life

- Are We There Yet?

- Darkness Falls

- Tears of the Sun

- xXx

- The Fog

- Radio

- Zoom

- Gigli

- Tomcats

Up Next: To quoth Phoebe Bridgers again: Yeah, I guess the end is here.