Welcome to Pictures of a Revolution, a year-by-year study of the output of Revolution Studios. This year, the whole enterprise begins to buckle, several once-respected directors are laid low on a massive scale, and some daddies run a day care.

The Prelude

Revolution’s 2002 was hampered by a bad decision made at the very start of its existence, before the problems with its first wave of titles became clear. Doubling down on teen comedies didn’t work no matter how hard they tried, the ceiling for those was never higher than “marginal success” and the sheer quantity of them made Revolution look like junk peddlers more than a proper studio. But the year still produced enough hits, including Revolution’s first bonafide blockbuster and its first (and only) Cannes award winner, that there was hope they could get their act together, especially now that they were shooting movies with some distance from the failures of the first year. In the New York Times profile I keep referencing, Joe Roth was certain that 2003 would be the year that would prove Revolution’s critics wrong, and looking at it on paper, it’s easy to see why. Revolution had five movies in 2001 and six in 2002, but this year they had ten, and almost all of those ten were led by big stars, not just the usual crew of flash-in-the-pans. And they were working in more genres than ever, covering their bases with every demographic. If this year didn’t do the trick, nothing would. And so nothing did.

The Films

If Revolution’s goal was to make tidy profits from medium-to-low-budget movies, it’s odd they didn’t have a horror movie ready to go sooner than this year. Horror is the one genre where it’s been proven that you don’t need stars and you don’t need much money to be successful, all you need are a few well-timed shocks and you’re well on your way to a healthy opening weekend at the very least. Sure enough, Revolution’s first horror movie, Darkness Falls ($47.5 million, $11 million budget), recouped its whole budget by its first U.S. weekend and ended its run pretty confidently in the black. It’s not exactly xXx money, but if they’d made five Darkness Fallses instead of five Tomcatses, they may have had a little more latitude to fail than they ended up having.

Whatever else you can say for it, Darkness Falls looks great. It’s shot by Dan Laustsen, the genre wizard who later shot Silent Hill, Crimson Peak, and every John Wick movie after the first one, and his chiaroscuro style is perfect for a story that revolves around lights being on and off (the monster, more or less an evil Tooth Fairy, can’t hurt you if you’re in the light). The opening scare sequence is a highlight, trading on every child’s fear of the dark by leaving pockets of darkness in the main character’s bedroom that are just big enough to hide the monster. Laustsen brings genuine atmosphere and class to a movie that otherwise specializes in the cheapest kind of cheap scares, loud orchestra stings, confusing rapid editing, and obvious fakeouts galore (never has an it-was-only-a-cat scare been more reminiscent of the Community “is someone throwing it?” gag). The artfully-clouded frames also disguise that the creature design isn’t very interesting, just a floating black hood and porcelain mask that’s much scarier as an off-screen threat or a featureless blur. Laustsen gets one good shot of the whole thing, the closing shot of the opening where it floats in the dark space between the wall and the doorway to a fully-illuminated bathroom.

The main problem with Darkness Falls is that there are no good actors in it. Emily Browning has two scenes in the first ten minutes as the child version of the female lead, but after she’s gone there’s not a single person who’s worthy of having a camera pointed at them. I don’t want to bag too much on the lead, Chaney Kley, since he died tragically young just a few years after this and perhaps I’ve just forgotten him doing great work as “Officer Asher” on the last four seasons of The Shield (by all means, sound off in the comments with any impressions of his Shield performance, I know at least one of you has to have some). But as I see him here, he is just not charismatic enough to lead a movie, and he doesn’t sell the burden of this character living in fear for his entire adult life. As older Emily Browning, Buffy regular Emma Caulfield is adequate and no more. And as Kley and Caulfield’s former childhood friend (and Caulfield’s current beau), no-name Grant Piro gives the kind of vaguely strained, unconvincing performance that suddenly makes a lot more sense when you find out the actor is Australian playing American (I felt the same way about whoever played Elisabeth Moss’s sister in The Invisible Man). Whenever the movie is just these people talking to each other, it’s DOA. That might be less of an issue if the scares were fun enough to compensate, but it’s deficient even on that level.

If you recall, when Revolution Studios was first announced, three A-list stars immediately signed up for three-picture deals with it: Julia Roberts, Adam Sandler, and Bruce Willis. Roberts was part of the first wave of Revolution titles with America’s Sweethearts (and she’ll have another one this year), Sandler gave his first Revolution lead performance in Punch-Drunk Love the next year (more on him in a second), and Willis finally came on-board this year with Tears of the Sun ($86.5 million, $100.5 million budget), an action epic about ethnic cleansing in Nigeria that was also director Antoine Fuqua’s follow-up to Training Day. As reported in The Philippine Star, the legendarily testy Willis did not get along with Fuqua on-set, fighting particularly hard about approaching the material as a gung-ho action movie with African Queen-style romance (Willis and Joe Roth’s idea) versus a more uncompromising look at genocide (Fuqua’s idea). There were numerous rewrites and recuts to try to split the difference between the two visions, and as it so often happens, the end result was too serious to appeal to the action-movie crowd and too dumb to be taken seriously as a meditation on violence.

The Phil Star article devotes several paragraphs to describing a sequence at the midpoint of Tears, where Willis and his team of Navy SEALs encounter a village being raided and torn apart by guerrilla soldiers. The way it’s described would make you think it’s a Come and See-esque endurance test of violent atrocities, but while it’s certainly violent, it makes little impact as it plays out. It’s a collection of context-free images of African suffering, enacted by people who have no character beyond being dead or being sad that they’re suffering, intercut with unexciting footage of Willis and Co. sniping guerrillas with silencers and making frowny faces when they see mutilated women and dead bodies. It’s not engaging as drama or action and it’s certainly not revelatory as a study of ethnic cleansing, all it accomplishes is showing that it sucks (which, yeah, sure) and that it makes Bruce Willis sad. It’s a nominally better treatment of African strife than previous Revolution production Black Hawk Down, but that movie is openly not about Somali conflict while this takes the even more offensive route of acting like it has something to say when it doesn’t. Black Hawk Down, for its problems on this subject, at least has the good sense to not be a White Savior movie, let alone a White Savior movie so shameless it has a scene where one of Willis’s few Black soldiers tells him that he’s doing a great thing by saving these Nigerians.

Roger Ebert’s review speaks of the three building blocks of Tears: “rain, cinematography and the face of Bruce Willis.” I have no complaints about the rain, whatever machines they were using worked like a charm. The cinematography is more of an issue, there are some nice landscape shots but the murky green-and-brown jungle aesthetic the movie spends much of its runtime in gets old real quick. And Bruce Willis’s face is the biggest problem of them all. Bruce Willis’s face must set the plot in motion, where Willis’s hardened, just-the-objective military man is awoken to the horrors that people can inflict on their fellow man; a close-up of his face in a rescue helicopter about to leave Nigeria must show the audience in real-time the shift where he realizes his moral, if not assigned, obligation to save as many lives as possible. Bruce Willis’s face is not up to this task, because it’s locked in the same goddamn pout in every shot. Every once in a while the pout gets slightly sadder, but mostly it’s a tough-guy pout so you know that Willis is a big strong Army man. It’s not that Willis can’t do subtle face acting, him in Unbreakable three years before is a brilliant performance built around what Willis can convey in tiny expressions. But here he gets stuck on his character’s gruffness and can’t go any further than that (or, very likely, he’s not trying to go any further as a fuck-you to Fuqua). It’s hilarious that he wanted more African Queen romance in this considering how much he fails to sell any kind of relationship with Monica Bellucci’s imperiled aid worker, I wouldn’t have been able to guess that was the original intention without reading about it ahead of time.

Punch-Drunk Love was the first Revolution movie to star Adam Sandler, but it was not an Adam Sandler Movie, which is what Joe Roth probably wanted from his Sandler deal in the first place. The Animal and The Master of Disguise were Adam Sandler Movies that did not star Adam Sandler, and those don’t make as much money as the real thing. So Revolution’s first Sandler-starring low-brow comedy, Anger Management ($195.7 million, $75 million budget), is the proper start to their relationship with Sandler, and it’s a big entrance. Before Anger Management, Sandler had been experiencing some ups and downs in what had previously been a meteoric rise. He probably didn’t expect Punch-Drunk Love to do Waterboy numbers, but the no-excuses failures of Little Nicky and Eight Crazy Nights, both genre/medium experiments within the Sandler-comedy mold, suggested there were limits to what directions audiences would follow Sandler in. The more straightforward Mr. Deeds was a hit and Anger Management‘s similar give-the-people-what-they-want approach made it a hit too. From here, Sandler is the king of Hollywood, beginning an uninterrupted run of $100 million-grossing comedies until That’s My Boy nine years later.

Anger Management is maybe the most meat-and-potatoes Sandler movie up to this point. It has no real high concept (“what if a guy went to anger management classes?” isn’t exactly shooting for the stars) and is built around delivering one thing it knows you like: Sandler getting mad. After Punch-Drunk Love made Sandler frightening, this restores his rage to its initial comedic conception, used as a hilarious tool against snobs and assholes. But there’s a key difference between this and the Sandler movies that come before and after, which is that this one is gives Sandler a screen (but not romantic) partner of equal, if not greater, stature. Sandler can be in the movie all he wants, but if you put Jack Nicholson in a movie, you’re setting him up to take it over. As written, this is a quintessential Jack character too, a man so charming that you understand why people would follow him even though he’s clearly out of his mind (he will park his car in the middle of a busy highway and make you sing “I Feel Pretty”, and you will treasure the opportunity to do so). Jack can do that in his sleep; hell, maybe this movie is him doing that in his sleep, as it should be. This is a movie about a man for whom every day is a struggle to control his emotions meeting a man who comes to every emotion, from lust to homicidal rage, with ease and a smile.

Jack also brings with him an element of adult sexuality that’s absent from prior Sandlers. Not that those movies weren’t concerned with sex, but Sandler plays so childish in them that their approach to sex doesn’t go far beyond “want to touch the heinie”. Jack very obviously wants to do much more than just touch the heinie, and Sandler is paranoid that him and any other man he’s intimidated by are going to fuck his girlfriend (Marisa Tomei). It’s here that Anger Management reveals what it’s really about, a battle of diametrically opposed brands of masculinity that sometimes literally comes down to a dick-measuring contest. Every comic setpiece eventually comes back to some form of emasculation or sexual humiliation, most thrillingly when Sandler confronts the bully who pantsed him in front of his girlfriend as a kid, now a Buddhist monk played by John C. Reilly. Turns out all it takes to get a monk to fist-fight you is telling them that you fucked their sister. When the movie is pushing its masculine anxieties into that level of violence or at least extreme oneupmanship, it’s riveting. Unfortunately, sometimes it plays those anxieties straight, particularly the excruciating scene where Woody Harrelson plays a trans sex worker whose existence and anatomy Sandler finds repulsive. There’s usually some scattered homophobic and transphobic jokes to briefly sour the mood of these otherwise pleasantly goofy Sandler comedies (at least until his last few Netflix movies, one of many reasons they’re among his best work), but this goes on for so long with no other jokes besides base fear of the other that it becomes hard for the movie to fully recover from it. And that’s before Harrelson returns for the climax, which also a). nonsensically reframes the movie as The Game and b). prominently and lovingly spotlights Rudy Giuliani.

2003 offered Revolution something neither of the previous years had; two big hits in a row. Daddy Day Care ($164.4 million, $60 million budget) was not a guaranteed smash either, since Eddie Murphy was coming off a 2002 where he made two disappointments (Showtime and I Spy) and one of the biggest bombs in film history (The Adventures of Pluto Nash). But more important was Murphy’s 2001, where he hit big as family-comedy star with Dr. Dolittle 2 and especially Shrek. If adult audiences had seen enough of Murphy’s schtick by this point, their kids loved him. The turn into family movies was the final step in removing whatever edge Murphy once possessed as a comic actor, but he’s still very funny in Daddy Day Care even working without swears or rapid-fire delivery. His relative restraint actually makes him the one connection to something like realism in a movie that’s otherwise just silliness, it’s a successful portrayal of a dad who’s funny but still thinks he’s funnier than he actually is.

Something I keep returning to in this series is how much the success of a formula studio movie is ultimately owed to its actors. When you’re working with material that’s as good as the average movie in that genre and no more, the right movie star in the lead or a strong supporting ensemble can be the difference between something enjoyable and something hopelessly bland. Daddy Day Care on the merits of its script should be the latter. If you look at the title and have seen one (1) kids comedy before, you will probably be able to construct an accurate and complete version of Daddy Day Care in your head. This is a movie bereft of surprises or anything but adherence to the most obvious cliches of its genre, many of which it fulfills with a half-hearted shrug (it could clearly care less about the arcs it gives to a handful of the day care kids, one kid goes from a little rage monster to a perfect gentleman entirely off-screen). I found out from my research that Roth put Daddy Day Care in pre-production within 24 hours of receiving the script, and perhaps a few more days of script work might’ve been advantageous to making this more than a serviceable checklist of beats. But Daddy Day Care is ultimately pretty fun because director Steve Carr has cast it very well, from Murphy down to seemingly thankless parts like the kid who’s a little less rambunctious than the other kids (a very young and already incredibly natural Elle Fanning), the supportive wife (Regina King), or the Child Services drone sent to inspect Daddy Day Care (Dr. Katz himself Jonathan Katz). Carr deserves special credit for the casting of the two sub-Murphy daddies of day care. The character of the goofy nerd who makes everything a Star Trek or comic-book reference is the most tired shit in the world, but when it’s Steve Zahn, who’s never met a stock doofus character he couldn’t lift up by sheer force of will, it becomes funny like few of these movies are. And Jeff Garlin, whose only major supporting experience at this time was Curb, is just money in the bank as an adult frustrated by children; there’s a reason he’s been plugging away on a family sitcom for nine seasons now.

Two hits in a row and then two flops in a row that sent once-beloved commercial auteurs to director’s jail. The first and much less notorious one is Hollywood Homicide ($51.1 million, $75 million budget), Ron Shelton’s stab at the buddy-cop comedy that was his last feature for 14 years (and judging by the non-reaction to its belated follow-up Just Getting Started, nobody seems to care that Shelton was gone). Three years earlier, Shelton’s previously can’t-miss sports-movie formula had produced a dud with the boxing drama Play it to the Bone, and Homicide was his second retreat into the cop-movie genre, after 2002’s Kurt Russell vehicle Dark Blue. I don’t think Shelton expected Dark Blue, a movie about police brutality penned in part by James Ellroy, to be a commercial juggernaut, but a splashy action-comedy about Harrison Ford being grumpy seems like an obvious moneymaker. Instead, it opened with slightly more money than the first weekend of Dumb and Dumberer: When Harry Met Lloyd and slightly less money than the first weekend of Rugrats Go Wild.

Hollywood Homicide does a few things that should be interesting wrinkles to the staid buddy-cop formula. One is that its buddy cops have been partners for a few months before the movie starts, so they’re neither comically mismatched with each other nor totally comfortable in each other’s presences yet. Another is that both men have side-hustles in addition to being police detectives, Joe Gavilan (Ford) is a real-estate broker and K.C. Calden (Josh Hartnett) is an aspiring actor and practicing yoga instructor. There’s ample opportunity for comic misadventures here, different careers crashing into each other and the unsteady rapport of these two men pushed to the limit by a case. Unfortunately, Hollywood Homicide is not a riotous farce, it’s sleepy-time. It’s hard to imagine a more low-energy action movie than the first 80 minutes of this, its idea of a funny foot chase is to have one guy wade around in a duck pond while Hartnett jogs around the perimeter of the duck pond for what feels like ages. A big part of the problem is that Ford and Hartnett have no chemistry together. I get no sense from any of their scenes of what their relationship could’ve possibly been in the months before the movie, or even really what their relationship is while the movie is happening; there’s no discernible dynamic between them except that they’re in scenes together. Wikipedia claims (with no source to back this up) that Ford and Hartnett didn’t get along on-set to the point that they could barely even talk to each other, and I buy it, both men’s uncomfortable underplaying of their scenes together 100% reads as them doing the bare minimum required of them conversing with each other. Hartnett gets some good moments elsewhere, but Ford is totally disconnected, this is the kind of performance people think of when they think of Ford clearly not giving a shit about the movie he’s in. To his credit, who could give a shit about this particular movie? The best I can say for the plot, where Isaiah Washington plays a Suge Knight-esque producer assassinating groups who want to leave his label, is that Shelton, a 57-year-old white man when this was in production, doesn’t totally embarrass himself with his insights into the hip-hop world. But the plot is still a dud, the mystery is too easy and Shelton doesn’t give enough room to let the great actors playing the villains (Washington, Dwight Yoakam, Bruce Greenwood) make an impression. If the movie can find no interest in a murder investigation, it sure can’t find interest in the subplot where Ford tries to sell Martin Landau’s mansion for some figure between $6 million and $7 million. Will Master P budge from his $6.5 million bid? I’m on the edge of my seat.

Hollywood Homicide ends up not being totally worthless on the back of the final half-hour, which is devoted almost exclusively to a car-turned-foot chase through L.A. It’s long and exhausting for everyone involved, necessitating several vehicle changes and hijackings (including Ford briefly taking a girl’s bicycle). When Hartnett does an action-movie-badass leap onto a merchandise stand, it completely fucks him up, he visibly has to work up the spirit to even stand up, let alone keep chasing after the bad guy. Every bystander Ford and Hartnett encounter, including the poor family whose minivan Hartnett steals with them still in it, is scared shitless by the whole thing and Shelton keeps cutting to their frightened reactions in a way that seems pointed. And above all the action is a mob of news helicopters all trying to make sense of what’s happening. It’s exciting not just because of the car stunts, but because you’re watching the implicit rules of an action sequence get repeatedly broken with intentionality, where usually out-of-sight out-of-mind considerations come to the forefront and make you consider this as an action-movie scene barging into something like the real world. It’s not exactly To Live and Die in L.A., but it might as well be coming after the rest of this dogshit movie. It’s the movie’s first clever idea that Shelton follows through with clever execution.

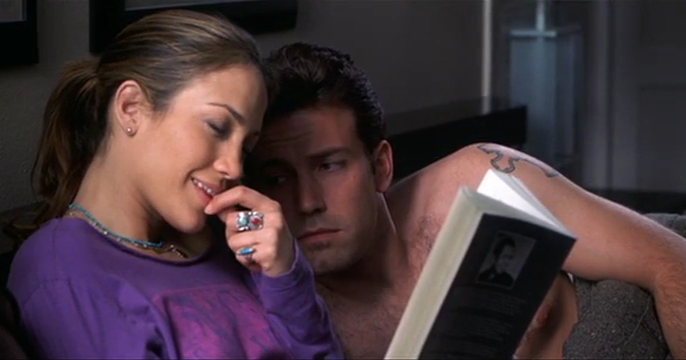

Hollywood Homicide and Tears of the Sun were flops in the normal Hollywood way, too much money thrown at shaky projects that audiences didn’t care for. That happens every year for every studio. A flop on the level of Gigli ($7.2 million, $75.6 million budget), however, is a shooting star. It’s obvious to see why it bombed: the title is awful, the budget is absurdly high for a low-stakes rom-com/crime caper, and of course everybody was sick of Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez by the time it came out. But those are reasons for an everyday bomb, it’s not often a movie sinks this low even when there’s more working against it. Ishtar had a full-on war fought against it by the trades and it still made more money than Gigli without even adjusting for inflation. For fuck’s sake, the head of Columbia publicly shittalked Ishtar and everyone who made it and yet Columbia didn’t pull it from as many theaters as possible on its second week like they later did for Gigli. That in particular is so unprecedented that the downtrodden interview Joe Roth did with with the Los Angeles Times a few days after Gigli‘s disastrous first weekend, before the decision was made by Columbia to cut their losses, estimates that it would “only” be a $35 million money-loser. Instead, it is the bomb to end all bombs, and certainly the one to end Martin Brest.

Often neglected when considering Gigli as a victim of the Bennifer hype machine is that they met filming this movie. It was shot in 2001 and by the time it limped into theaters two years later, America had gone through the complete arc of falling in love with Bennifer and growing tired of them. With this in mind, Gigli becomes something like a Greek tragedy, an inadvertent creator of its own brutal demise. Looking at production trivia, it seems even more like the invisible hand of fate was guiding Gigli towards an ignoble end; Halle Berry was the original first choice for the Lopez part and had to drop out to shoot X2, and Lopez only came on-board because the movie she was going to shoot at the time, another Columbia release called Tick Tock, had its production delayed and eventually cancelled because of 9/11 (its plot concerned terrorist bombings in Los Angeles). So many pieces had to fall in place just right so that Gigli became a landmark flop. It all came so close to never happening. This death came so close to never happening.

Anyway, Gigli fucking sucks. Five years earlier, Martin Brest directed Meet Joe Black, a three-hour behemoth where every actor has been directed to move and talk so slowly that those three hours feel like they last a month. Gigli should be Brest’s comeback, returning to his bread-and-butter of crime-comedies (as opposed to turgid dramas about the human spirit or whatever) and most importantly being an hour shorter than Black. But no, it’s somehow exactly as mind-numbing as Black. Every scene plods along at exactly the same pace with exactly the same set-up, a character delivers an interminable monologue where they use five words when one word would do. If the character doing the monologuing is Lopez, Affleck acts confused by what she’s saying. If the character doing the monologuing is Affleck, Lopez acts charmed by what he’s saying. In-between this, Brest will throw in a line or two from Justin Bartha doing a horrible caricature of a mentally handicapped man, because him shouting non-sequiturs is the only thing that would be recognizable as a joke in the scene (occasionally, he’ll instead say some vaguely profound/sad thing while sentimental strings play on the soundtrack, or he’ll sing random hip-hop songs, god this fucking piece of shit). It is punishing to watch the cycle repeat itself over and over with no modulation. Christopher Walken’s one scene rightfully gets singled out as a highlight because Walken’s unpredictable energy feels like it’s leading the movie into uncharted territory for once, even if he’s just saying the same dumb words as everyone else. The bored lust with which he describes Marie Callender’s pie is proof that an actor can make anything into poetry if they try hard enough. Al Pacino is the same way in his one scene as an unhinged mob boss, he comes from the Mamet school where dialogue is off-kilter music and that’s a much better way to handle these flowery soliloquies than Affleck and Lopez try. They just seem uncomfortable with the words coming out of their mouths, particularly Lopez who gets saddled with the worst of the dictionary words (she threatens to gouge someone’s eyes out by calling the act “digital orb extrusion”). Add on top of that the abysmal dynamic of Lopez playing a lesbian looking for a good-enough dick to fuck her straight and you have 95% or so of a movie that’s completely unactable (of course, even considering that, Bartha should still be in prison for this performance). Cinematographer Robert Elswit (who shot this the same year he shot Punch-Drunk Love) gave a candid statement about this movie in 2014, saying that Brest, for all his talents as a director, “made a horrible mistake” by writing the screenplay himself and the result was something that “was just not a film” no matter how hard everybody tried to make it one. And he’s right, an actual screenwriter would give this some kind of structure or rhythm but Brest only writes to hear himself, not even his actors, talk.

Oh, how I wish I was a fly on the wall of Joe Roth’s office when he made the call to double down on reprehensible portrayals of the mentally handicapped this year. In the annals of This Had Oscar Buzz history, few failed Oscar plays are quite as widely loathed as Radio ($52.6 million, $30 million budget). It was hated at the time, too shameless in its inspiration-porn aspirations even for the Academy, and it seems to have been the deciding factor to make America give up on Cuba Gooding Jr. once and for all. And yet it’s somehow only gotten more loathsome with time, as views on disability have progressed and Tropic Thunder has killed this kind of performance and movie dead.

The problems with Radio become evident very quickly. Before there are even any images besides the Columbia and Revolution logos, the solo female vocalist in James Horner’s score is violently tugging at the audience’s heartstrings. Then the movie proper starts with a sweeping crane shot of train tracks and narration (from the otherwise disgracefully underused Debra Winger) saying, in almost exactly these words, that everything changed the year Radio entered their lives. There’s nothing there to distinguish Radio from a CollegeHumor parody of Oscar bait, and nothing afterwards either. Radio is exactly what you think it is, overburdened by sap and attempting to have its cake and eat it too by playing Radio’s disability for both easy laughs (tee hee, he’s asking Ed Harris what pants to wear over the phone) and cheap sentiment; Radio is not a human being, he’s a whimsical imp beloved by all but the meanest bullies in town. It’s appalling but in a completely boring way, as predictable as its pushy Horner score and Super Sounds of the 70s soundtrack. Occasionally the movie will go far enough in its ham-handedness that it gets a bad laugh, like the twist(?) that the mean banker who doesn’t like Radio is the father of the mean jock who also doesn’t like Radio (they’re the O’Doyles of Anderson, South Carolina) or how every other word out of Radio’s mother is about how much work she has to do before she drops dead from working too much. But mostly it just sucks in ways that aren’t fun. Not even the script having the gall to make Ed Harris actually say “We’re not the ones who’ve been teachin’ Radio, Radio’s the one who’s been teachin’ us” got a rise out of me.

It should go without saying that Cuba Gooding Jr. is extremely bad in Radio. He was already a limited actor even before his career went into freefall, he’s decent in Boyz n the Hood but outshone by almost everyone else in that cast and a lot of fun in Jerry Maguire because that part rewards his all-showboating-no-substance approach (and he’s at most the third best supporting performance in it, definitely below Regina King and Bonnie Hunt and maybe below Lipnicki too). He can’t help but do too much, and if that approach is merely annoying in something like Rat Race (already a movie not renowned for its subtle performances), it becomes disgusting here. His overthought hand gestures and sing-songy vocal affectations, I have nothing to say except that they’re awful and surface-level tics rather than any kind of actual attempt to make Radio a person. Even just the way he perpetually keeps his mouth open just enough so you can see his goofy prosthetic teeth is too much effort only in service of making the viewer notice the effort. That Radio is ultimately a supporting player in his own story is part of the problem (we’re asked to care an awful lot about Radio’s education when we see almost none of it), but it’s also a small mercy that Cuba is on-screen as little as possible. The actual main character is Ed Harris, who’s about as decent as this material can allow him to be; he gets a monologue about encountering a handicapped boy on his paper route as a child that he handles pretty well, though even he can’t make the hard sell that Radio’s the one who’s been teachin’ us. He also gets some lame business about how he’s more attentive to football than his daughter, I don’t fucking care but at least it’s not Cuba jerking off an invisible Oscar.

In the aftermath of Gigli, Roth said Revolution wouldn’t be working with any more final-cut directors. But that came with the asterisk “except Ron Howard”. As laughable as it may now seem to consider Howard that kind of auteur, look at the list of hacks who directed Revolution movies before him and he might as well be David Fincher. Especially as he stands in 2003, hot off A Beautiful Mind and ready to cash his chips in on a lengthy, violent western, The Missing ($38.4 million, $60 million budget). Since so much of what Revolution touches gets cursed, of course Howard’s one attempt at something like a passion project was a bomb for them.

For years, people have been stumped by the question of what a “Ron Howard movie” is, considering how often Howard switches genres and styles. If an answer has been decided upon, it’s that a Ron Howard movie is audience-pleasing, easily-digestible pablum with big stars, but even that’s not always true. Case in point: The Missing. It opens with Cate Blanchett in an outhouse, about to wipe with shredded newspaper. When she’s done, she goes to an old lady whose only remaining tooth is black from infection, and yanks the tooth out with pliers (on-screen, no less). It’s a helluva tone-setting opening and it makes immediately clear why this was neither an audience nor an awards favorite; it’s a movie that exists to rub the viewer’s face in the nastiness of the Old West, no prestige gloss to make it more palatable. Sandwiched between the two schmaltziest feel-good movies in his filmography, Beautiful Mind and Cinderella Man, it reveals that Howard is surprisingly adept at this kind of grim, disreputable genre storytelling (he clearly relishes the visual opportunities it provides, letting scenes go almost completely dark and limiting even the landscape shots to shades of blue and white). Howard gets the (usually not unfair) rap of being store-brand Spielberg, but post-Jaws Spielberg wouldn’t dare harm a child, while this kills a baby with fever and then has the mother (a young Elisabeth Moss) blow her brains out. Perhaps the Howard sentimentality comes out in the central story of Blanchett coming to terms with her long-absent father (Tommy Lee Jones), but their reconciliation is so tentative and unresolved even by the end of the movie that it never registers as sap. Both Blanchett and Jones are such no-bullshit actors that it seems against their nature to hug and make up, and thankfully Howard understands that and accentuates it with a superb performance from Jenna Boyd as Blanchett’s younger daughter, so devoid of kid-actor cuteness you’d think she actually lived in the 1800s and had the cuteness taken out of her the hard way.

In addition to including all the R-rated violence John Ford could only dream of filming, The Missing sets out to correct the obviously flawed racial and gender dynamics of the western genre, putting women in the lead and directly dealing with the mistreatment of Native Americans at the time. A worse movie would emphasize those points so much that they become offensive in a different way than the original cliches, a masturbation session for white liberals. But credit to Howard and screenwriter Ken Kaufman for weaving these contemporary updates into the story without calling attention to them; it’s a genre yarn at heart with progressive ornamentation. Howard deserves special credit for committing to large stretches of the movie being spoken in easily understood and subtitled Apache dialect, a choice that would go unnoticed to 99% of its audience but registers as shockingly radical to that 1%. An Associated Press article at the time can’t find another movie that did this (usually when Native Americans speak in movies, it’s in Navajo) and describes young Apaches thrilled by seeing a movie that removes the distance between them and their heritage. This series has covered and will cover many movies that left no cultural footprint, so it’s nice to cover something that made a positive impact on the world even when bombing.

Film Twitter luminary FilmBart had a tweet that described the Julia Roberts weepie Stepmom as part of a genre of “contrived melodramas that aren’t good but have movie stars and that autumnal palette that makes everything feel like it’s shot inside a Barnes and Noble.” That tweet rang clearly in my ears while I watched Mona Lisa Smile ($141.3 million, $72.3 million budget), another Julia Roberts vehicle that’s all coziness and not much substance. The Barnes and Noble comment may apply even more strongly here, it has the deep-brown color palette and artificially pleasant atmosphere, but also a surface-level celebration of early-to-mid 20th century artworks. It’s ostensibly a movie about minds getting opened to the myriad possibilities of art, but it can’t find a more creative way to express than that a brief scene of Roberts and her students looking very close at a Jackson Pollock canvas (even its way of shooting the art is secondhand, director Mike Newell frames the canvas in an obvious echo of the monolith from 2001). The art discussion feeds into the movie’s similarly bland takes on womanhood in the 1950s, it takes the bold stance that every woman should choose her own path rather than have it institutionally decided for her. We get at least one milquetoast “how far we’ve come” moment per scene, often about how women don’t need to get married if they don’t want to (but also they can if they want to), but sometimes about birth control (good that it’s no longer illegal) and lesbianism (good that it’s no longer so strongly stigmatized). Obviously, putting those issues in the misty lens of the past isn’t helpful and certainly isn’t as subversive as the movie seems to think it is, and yet I find it hard to get mad at Mona Lisa Smile. Hell, I kinda like it. The Stepmom aesthetic is definitely part of that, and I mourn how it went extinct in the years following this. As much as I’m agnostic on film vs. digital, digital simply can’t match 35mm for capturing this kind of warm but not overbearing look, like you’re watching the movie while snuggled under a blanket. It’s under this soothing atmosphere that Mona Lisa Smile‘s toothless feints at progressiveness feel just right. It’s the most scrubbed-clean version of feminism, but it’s so goshdarn relaxing.

Roberts’ performance here comes in the middle of a run that’s relatively risk-taking for someone with the “America’s sweetheart” banner. Her two Revolution movies, this and America’s Sweethearts, are the only traditional Roberts movies in the middle of a run that includes four Soderbergh movies commenting on and messing with her star persona, The Mexican, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, and Closer; I don’t even like all of those movies, but they show a willingness to branch out of her comfort zone that’s inspiring for a star on her level. Mona Lisa Smile is pitched dead-center in her comfort zone, she flashes that luminous smile and charms her way into the hearts of her impressionable students. It’s familiar, but it works every time. And if it does nothing else right, Mona Lisa Smile presents a wonderful array of screen partners for her to bounce off of. The main quartet of Roberts’ students are Kirsten Dunst (as the snobby upper-class girl), Julia Stiles (as the nice upper-class girl), Maggie Gyllenhaal (as the free spirit), and Ginnifer Goodwin (as the shy one), a fine cross-section of 2003’s most promising young actresses. Even as the script is hilariously schematic in how it writes their characters (there are four of them so exactly half end up with a man and half don’t), they share an easy camaraderie together and with Roberts that makes them register as more than the stock types they represent. I rolled my eyes at the contrived drama each girl goes through, but damned if the performances didn’t endear them to me enough that I got a little emotional at the end, when they all tearily ride their bikes to say goodbye to Roberts and thank her for changing their lives.

In November 2003, entertainment journalist Anne Thompson wrote a New York Magazine profile on Revolution’s rocky year. Thompson frames the three Revolution 2003 movies that hadn’t yet come out as being pivotal in either making or breaking the company. The first, The Missing, was another fall-on-its-face bomb. The second, Mona Lisa Smile, was saved by overseas numbers pushing it past the $100 million mark but even then wasn’t a breakout hit, Roth should just have been thankful it didn’t do worse. The third, Peter Pan ($122 million, $130 million budget), was the nearest and dearest to Roth’s heart, being a project he was pushing for even during his tenure at Disney (his wish for a live-action Peter Pan at Disney finally came true this year, he’s a producer on David Lowery’s forthcoming Peter Pan and Wendy). His passion must’ve been infectious enough that he could rope in Universal to distribute it and provide a third of its mammoth budget, even while, like Columbia, giving them no creative control over it. It was Revolution’s biggest gamble up to this point, and one of their most debilitating failures. To be fair to Revolution, much of its lack of box office success can be attributed to the brain-geniuses at Universal opening another fantasy action epic the week after goddamn Return of the King. To be unfair to Revolution, $130 million is quite a lot of money to blow on a movie with no stars bigger than Jason Isaacs and no real marketing hook besides the vague notion of being a little darker than the Disney movie. Now, I think it’s a terrific movie that I’m glad they made this way on this scale, but objectively speaking it’s not a great move after you’ve already thrown so much money into a Martin Brest-shaped fire pit.

I doubt the largely unknown cast got much of that $130 million, but whatever they got was money well spent. The few slight “names” of the cast are all a lot of fun, particularly Ludivine Sagnier as an asshole Tinkerbell and Olivia Williams as the Darling family matriarch. Isaacs is unsurprisingly the MVP, he’s got the versatility to do equally well hamming it up as Captain Hook and playing Mr. Darling as the man with the perpetual nervousness. But he could be great and the movie would still suck if the wrong kids were Peter and Wendy, and this knocks it out of the park in that area. Rachel Hurd-Wood is so winning as Wendy that it purposely unbalances the movie, you can’t help but take her side against Peter’s every time. And accordingly, Jeremy Sumpter plays Peter as a little bit of a snot, as only someone stuck in lifelong prepubescence could be. Their dynamic has actual tension lacking from so many other versions of this story, most obviously in the “incoming adulthood vs. eternal youth” way but there’s also nascent sexual tension at play. Hurd-Wood and Sumpter excel at playing equally unknowledgeable and uncomfortable with what they’re feeling, and their varying reactions to that will eventually be what keeps them apart forever.

One of the reasons directors keep coming back to Peter Pan, despite it being the most well-trodden material in the world, is that it gives ample opportunity to create vivid fantasy lands (or if you’re the Beasts of the Southern Wild guy, to go to some island somewhere and shoot it like a Levi’s commercial). From the first moments of this movie’s storybook vision of London, where the sky is an impossible shade of blue and the sun is always setting, the care and fun that director P.J. Hogan and his crew have put into every design element is plainly obvious (special shout-out to cinematographer Donald McAlpine, who contributed inventive 2.35:1 compositions to both this and Anger Management). This was made at just the right time in the development of CGI, when it was just good enough to pass for photoreal but still inherently cartoony enough to divorce itself from the real world; it’s not a crutch like it got to be around this time and beyond, it’s a purposeful tool to create a world sillier and more dynamic than our own. I have nothing but compliments about it on a visual level, and the advertising trying desperately to hide its candy colors and weightlessness in favor of making it look like a dark action-adventure (complete with melancholic Coldplay soundtrack) is baffling to me. Even in its most morbid moments (Captain Hook is quite fond of stabbing and shooting his underlings), it’s the whimsical violence of a children’s story, the kind that’s just another exciting part of the adventure. In theory I get the post-Lord of the Rings instinct to sell your fantasy movie as not just for babies (though, again, marketing as an imitation LotR against actual LotR is the major-studio equivalent of suicide-by-cop), but a gritty Peter Pan would just seem silly to adults and too scary for kids (just look what happened to Pan). This Peter Pan is perfect for both kids and adults, and not in the dumb Shrek sense; kids will like it because it looks like their imaginations captured on-screen and adults will like it because it explores children’s imaginations with surprising depth and nuance (while still being a blast). It’s about the brief timeframe when children’s heads are still full of crazy stories but the first notions of adulthood are beginning to intrude, the time when the tale of Peter Pan and escaping those worries is most alluring. By the end the movie becomes about the importance of telling the story of Peter Pan to children, so that they can have a fun, dynamic outlet to work out their feelings and know that others feel them too, and then share it with their own children when they feel the same way.

The Conclusion

Wasn’t Revolution supposed to be the studio that said no to waste and bloated budgets? So many of these movies would be obvious bad investments even at more reasonable price points, and as they stand they’re monuments to Hollywood accounting at its worst and least sensical. But there are some major highs even in a year defined by extreme lows, and for its financial excess, Peter Pan taps into something like genuine movie magic. I won’t say that they were onto something, because five of these ten movies suck in debilitating ways. But there’s still a glimmer of potential here, even when the bottom is dropping out.

The Ranking (so far):

- Punch-Drunk Love

- Peter Pan

- Black Hawk Down

- The Missing

- The One

- Stealing Harvard

- Anger Management

- Mona Lisa Smile

- Daddy Day Care

- The New Guy

- Maid in Manhattan

- The Animal

- Hollywood Homicide

- America’s Sweethearts

- The Master of Disguise

- Darkness Falls

- Tears of the Sun

- xXx

- Radio

- Gigli

- Tomcats

Up Next: Revolution makes its way uptown, walking fast, faces pass and it’s homebound.