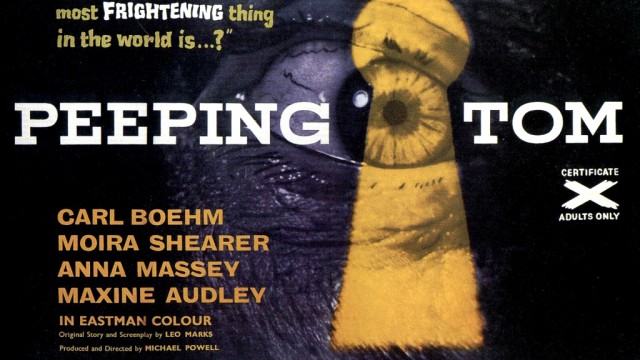

In honor of Halloween week, I will be looking at three classic British horror films. We start with Peeping Tom.

In 1960, the release of two films changed how we view cinematic horror. One was an American, low budget, black-and-white ‘artistic’ exploitation thriller, directed by the Master of Suspense. The other was a British, Technicolor ‘artistic’ exploitation thriller, directed by the man best known as one half of The Archers. Both were highly controversial, but one was lauded the breakthrough of modern horror, another high for the director. The other was so savaged, it essentially destroyed the director’s career. Of course I’m talking about Psycho and Peeping Tom. To those unfamiliar, Psycho was the grand success, and Peeping Tom was the failure. These days, the status of Psycho as a horror classic is undisputed, but Peeping Tom, to use a cliché, is the boogeyman that still haunts the genre. It goes without saying horror has grown more and more gruesome in the years that have followed, but Peeping Tom is still one of the few timelessly disturbing films.

Eye of the Beholder: The POV of Peeping Tom

The movies make us into voyeurs. We sit in the dark, watching other people’s lives. It is the bargain the cinema strikes with us, although most films are too well-behaved to mention it.

-Roger Ebert’s introduction to his Peeping Tom ‘Great Movies’ review.

The film opens with a POV from an unknown man’s portable camera. It’s focused on a streetwalker, who invites the man to her room. The camera is fixed on her, and we the audience become more acutely aware the woman is about to meet a grisly end. Our suspicions are confirmed as we see her terrified, dying face. The film follows Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm), a shy, secretive production assistant who yearns to be a filmmaker. He is also a serial killer who stalks and kills women, who records their dying expressions as he stabs them with a knife attached to his portable camera. As he terrorizes London, he finds himself drawn into a peculiar friendship with Helen Stephens (Anna Massey), the sweet, friendly girl whose family rents a flat in Lewis’s house.

Peeping Tom is not the first film to explore voyeurism, particularly within the realm of the thriller/horror genre. Hitchcock had already explored the theme numerous times to masterful effect. Rear Window is his best known film about the thrills of voyeurism. However, a film like Rear Window softens the voyeuristic elements, while never losing the taut atmosphere, by placing the voyeur in danger. The audience’s sympathies are with this likable man and those closest to him. As Mr. Ebert notes in his review, films like Rear Window and Peeping Tom shatter the illusion the audience are not voyeurs when they watch a film. The key difference is Peeping Tom positions the audience so they are seeing everything through the eyes of the killer.

Beastly Beauty: Who is Mark Lewis?

As far as legendary cinematic psychopaths go, Mark Lewis does not possess the same household recognition of characters like Norman Bates or Hannibal Lecter. His lack of flamboyance leaves him paradoxically undistinguished and all the more creepy because of it. He is not the methodical slasher lurking in the shadows nor is he the wise-cracking lunatic. Beohm’s naturally melancholic features imbue a deep sadness in his character; if it weren’t for his rather unpleasant habit of killing people and recording them as they die, he’d just be that sad, marginally less creepy fellow with a poor separation between work and his social life.

Mark Lewis is a British man, and yet in a sly bit of casting, Karlheinz Böhm (Anglicanized to Carl Boehm) is anything but British. Powell initially asked if English actors Laurence Harvey and Dirk Bogarde would play the lead, but they both declined (Bogarde chose instead to star in another controversial film, Victim). His accent gives an off-kilter quality to his whole character; something just seems off about him. Foreignness as a giveaway for a sinister character is not a novel concept, but Powell never draws explicit attention to it. It’s just another facet of Lewis’s personality, one that hints the man does not fit in with his surroundings.

The sadness of Mark Lewis, beyond his saturnine appearance, is gradually teased out through the film, which delves into his troubled childhood. As a rule of thumb, finding out the backstory to the antagonist ruins their aura of horror. In the case of Mark Lewis, it only highlights his horrifying actions. The viewer ultimately understands why he is the way he is, but the reveal shifts the audience’s POV from Lewis to his acquaintance, Helen Stephens.

Ingenue and Final Girl: Who is Helen Stephens?

Helen Stephens is ostensibly the film’s ingenue and later its final girl. However, it feels oddly reductive to assign her those labels, true as they may be. As Mark’s downstairs neighbor and tenant, she reaches out to him, wanting to be his friend. Her radiant cheerfulness and friendly nature are noted contrast of Mark’s sullen, reserved personality. The audience is introduced to her at her birthday party; she spots Mark spying on the celebration, and instead of reacting with horror or anger, she invites him to join the festivities. She is so pleasant and kind, Mark is uncertain how to respond. So is the audience. Is she the pretty butterfly waiting to be squished? Thankfully, Massey’s incandescent performance (she is my choice for one of the best character actresses of her generation), textures Helen’s warmth so to not simply be the film’s smiling fool who awaits her grim end. She is genuinely curious in Mark; maybe she senses his danger, but she appears more acutely aware of his hidden pain.

Helen also represents a peculiar commentary on the film’s POV. It is revealed that Mark’s father liked to terrorize his son, recording his reaction, to study the science of fear (the Freudian details in the film are so plentiful, one could write a book). Mark shows one of these recordings to Helen, and she is horrified by what she sees. This later repeated when Helen watches a film of Mark killing a woman. In the first instance, given what little the audience knows of Mark, the POV arguably shifts from him to Helen. However, when Helen finally watches one of Mark’s films, we the audience already know who the man is and what he has done. So, who’s point-of-view is it? I would argue it is still Mark’s, as he appears shortly afterwards. But, that scene sends a ripple through the film to the audience: we know what Helen will find and there is no escaping we are all voyeurs, just like Mark.

Peeping Tom and Modern Horror Cinema

A large part of Peeping Tom can be attributed to Martin Scorsese, who rescued the film from being a largely forgotten cult oddity. He called the film, along with 8½, the two that best capture the filmmaking process: ‘8½ captures the glamour and enjoyment of film-making, while Peeping Tom shows the aggression of it, how the camera violates… From studying them you can discover everything about people who make films, or at least people who express themselves through films.’ This is high praise for a film once dismissed on the British press as fit only to be disposed in a sewer. However, the critical appraisal has since shift and now the film is considered one of the finest horror flicks ever made.

It is almost redundant to say that Peeping Tom is a landmark horror film whose DNA can be found in countless other movies, particularly those in the slasher genre. Black Christmas and Halloween would similarly use the killer’s POV, and in the process spawned a sub genre that would use gore and general stupidity as crutches in films largely distinguished in what number came after the title. The terrifying novelty of watching from the killer’s perspective, like all novelties, would inevitably wear off. However, years after its realize, the film’s piquancy hasn’t dimmed. It may not be gruesome like many horror films today, but it’s implication of the audience with the killer’s point-of-view, along with its suggestion we are all voyeurs, albeit in a more socially acceptable form, still retain the power to haunt and disturb.

It truly is the boogeyman in a genre with no shortage of them.