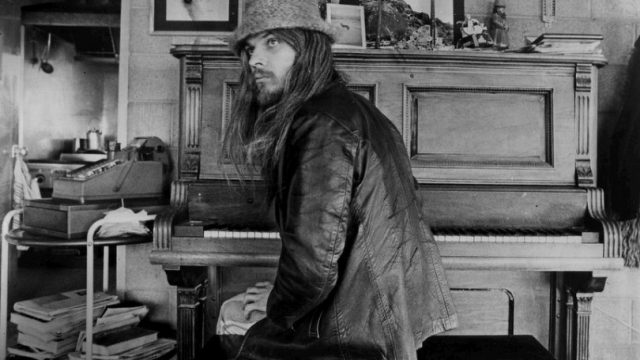

Completed in 1974 by Les Blank, A Poem Is a Naked Person was supposed to have been a documentary of Leon Russell on tour, intercut with scenes of the making of his small-scale masterpiece, Hank Wilson’s Back!, an album of covers of country and bluegrass standards that isn’t simply faithful to the source material; it sounds as if Russell is channeling the inspiration that created the songs in the first place. Overall, we’d expect the film, commissioned by Russell, to serve as another chapter in the Great Men of Rock History.

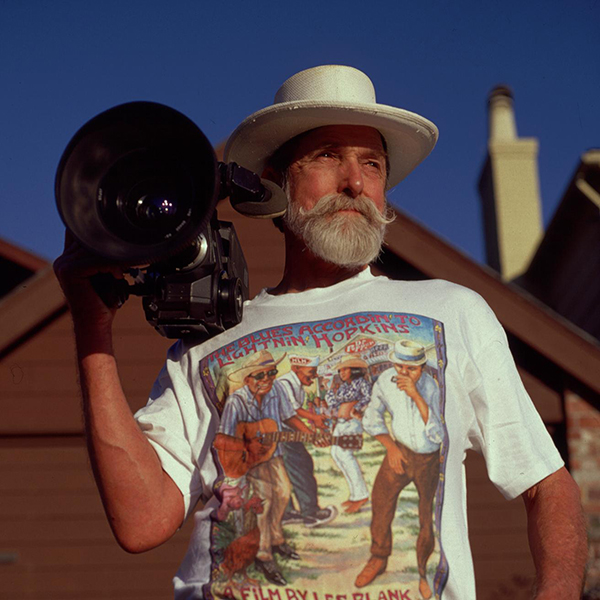

But Russell’s reluctance to participate in a traditional way, by slowing down his speedy pace of performing and recording to do filmed interviews, and Blank’s alcohol-fueled antics that at one point got the film crew thrown off the tour catalyzed a move away from the center and to the periphery of Russell’s traveling circus. Rather than dutifully add a few tasteful splashes of local color, Blank acts as a cultural anthropologist, contextualizing the musician as another ritualistic figure in a society where any number of ceremonial spectacles abound.

Russell plays piano at a friend’s wedding. Blank captures all of the well-known trappings of the countercultural movement, that started in the late 60s and continued into the 70s, opening with a little girl on the front porch belting out “Joy to the World.” Moving into the house, we see the minister in a rather stiffly formal manner conduct the ceremony then Russell plays the wedding march before shifting into a boogie-woogie groove. The party begins.

Just as we’re about to feel that we’re a part of Russell’s inner circle, Blank cuts to a skydiver, another sort of freaky guy who toasts the film crew, drains his beer, and tries to eat the glass, but it won’t break. From there, we move to an African American man working on Russell’s mansion.

Blank is showing us that a larger community is out there, with country performers such as Willie Nelson (before he grew his iconic beard), the conservative-looking session men with which Russell records Hank Wilson’s Back!, the audiences Russell encounters on tour, his multicultural band of men and women, construction workers, and musicians aspiring to Russell’s level of success—assembled together by Blank’s editing which includes “mistakes,” like that unbreakable beer glass.

We might say, of course, this is what film has always done: particularly in how it captures a time and place. What makes A Poem ahead of its time, and a masterpiece of documentary film making, is its anticipation of being seen as nostalgia, which it willfully resists. In an infamous sequence, a hippie artist talks about consumerism while feeding a baby chick to his snake. No matter how you look at it, it’s an ugly, jarring scene.

We might say, of course, this is what film has always done: particularly in how it captures a time and place. What makes A Poem ahead of its time, and a masterpiece of documentary film making, is its anticipation of being seen as nostalgia, which it willfully resists. In an infamous sequence, a hippie artist talks about consumerism while feeding a baby chick to his snake. No matter how you look at it, it’s an ugly, jarring scene.

If nostalgia reduces past reality to a comfortable fantasy of the way things used to be, A Poem is forward looking, depicting a natural order of things that precedes us—and will endure after we’re gone. That’s not to say that nature need be red in tooth and claw; it’s rather to insist that art is connected with, not apart from, the environment. In a meditative interlude, a gorgeous sunset on the water is accompanied by Russell’s heartfelt rendition of “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.”

The snake eating the chick is juxtaposed against the demolition of a building: cycles of destruction that enable creation. You get the impression that this is what Blank most likes about Russell: his music enters a kind of timeless realm.

When Blank showed Russell the completed film, Russell realized he got considerably more than what he bargained for. Although Russell came up with the title for the film (as Kent Jones explains, the title was taken from the liner notes, written by Bob Dylan, for Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home record), Blank emphasized the notion of a communal, free-flowing “poem” over a more conventionally tight focus on the “person” of Russell.

Because Russell kept control over the film, Blank could only show his own print during private, noncommercial screenings. Always claiming A Poem was a masterpiece, Blank continued to tinker with the film, making it a work in progress. In a further twist of fate, Blank’s son reached out to Russell when his father’s health was rapidly failing. Russell said he liked the son far more than the father, and agreed, at long last, to release the film.

Needless to say, the context for viewing the long-awaited film, made available just last year, has changed. As I’ve suggested, the film’s political outlook is geared to the future, not the time in which it was made. Everything the film cautioned us in 1974 not to take for granted, centering on ideas about community and environment, is up in the air.

Indeed, the film at the end leaves us up in the air. We hear a rare interview with Russell, conducted by Blank, while we watch a bird in flight. Blank asks Russell why people fear death. Russell replies that it’s because people fear the unknown. A reply that appears to point at the root cause for the uncertainty in this country. When a building comes down, there is no longer the guarantee another will be built.

At the end of a concert, Russell puts on a top hat adorned with stars and bids farewell to the audience. Blank has filmed a moment in American life—in, I think, a metaphysical way, as a feeling, a spirit, an art form. At the time, Russell and Blank knew it would all continue; who could’ve argued otherwise?

At the end of a concert, Russell puts on a top hat adorned with stars and bids farewell to the audience. Blank has filmed a moment in American life—in, I think, a metaphysical way, as a feeling, a spirit, an art form. At the time, Russell and Blank knew it would all continue; who could’ve argued otherwise?

They’re both gone, which is, granted, inevitable—Russell departed less than a month prior. A Poem, as we watch it now, is a masterful elegy.