Lately, I’ve been thinking about influence.

Influence is a funny thing. An artist cannot be untouched by it. Every five minute short, every four-hour road show epic, and every weeklong miniseries will have on it the markings, or rather, the seeds, of a prior artist. Even the Lumière Brothers were infected by the influence of the magic shows, still photographs, and theatrical spectacles of their era. Perhaps at the beginning of time there was a Great and Original Artist, the Primordial Filmmaker who handed down to man the original two-reeler before being punished by the gods, and everything that’s been scripted or filmed since then has just been a protracted passing down of that first cinematic spark.

And no matter how much influence or inspiration a young artist takes from an earlier artist, if they are truly worth their salt they will produce some element, some vestige that is theirs and theirs alone.

In his book The Anxiety of Influence, literary critic Harold Bloom argued that all great poets are essentially students who misunderstand their teacher; that in their attempts to create something new, they pass on the themes and readings of their most inspiring poet, but fundamentally “misread” them in some way, creating a new kind of poetry. If that’s true — and it is an intriguing notion, if not an instantly agreeable one — then that idea can be extended to film.

But what if a filmmaker doesn’t walk away from the road allusion and influence? What if someone at the height of their skills and craft uses those skills in imitation and replication, and not necessarily in creation?

Sometimes, in fact, a director (especially great directors) will choose to “cover,” more-or-less, another director’s style. Yet this often leads to mixed results. Sometimes, as my colleague Grant “Wallflower” Nebel pointed out in his brilliant review of the Kubrick-Spielberg Frankenstein monster A.I., at times the sensibilities of two artists will seem ultimately incompatible in some way that will create jutting edges in a work that might otherwise be smooth and form-fitting.

When I think on this, I think of Francis Ford Coppola, creator of some of the finest American films of his era, and who spent the decade of 1970s building a body of work that would make any filmmaker envious, and then who, in the ’80s, decided to do weird little experiments like Frank Capra homage Tucker: The Man and His Dream, a beautifully cornball tribute to an obscure failed inventor. The finished product is a true oddball, a curious and clearly passionate combination of the man behind Apocalypse Now and the man behind Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. Yet it works. In spite of itself, because of itself, whatever — it simply works.

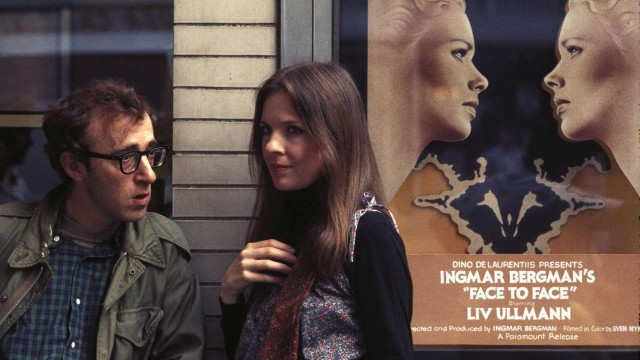

Or I think about Woody Allen doing Ingmar Bergman for Interiors. Or Brian DePalma doing Hitchcock in about half of his movies. These are incredible filmmakers who are desirous to walk around in the skin of another filmmaker for the time it takes to create a movie: sometimes the results are sublime; at other times they may be grotesque, like the bug in Men in Black wearing a shoddy Vincent D’Onofrio suit.

In the comments below, please feel free to talk about what your favorite examples of one director “covering” another are, or what your least favorite examples are, or anything that lies in-between. We’re all listening.