Was there, will there ever be, a man better at going from quiet neurosis to sheer over-the-top mania than Gene Wilder? I almost hope not. He seems to have perfected the form.

1974’s Young Frankenstein is one of the best examples of his art. The first time we see his Frankenstein (not the monster or the original Dr. Frankenstein, but the doctor’s grandson) he is focused and withdrawn, if slightly eccentric and a bit touchy about his name. But soon enough, he too has a corpse strapped to a table as lightning crashes, ready to create life from death. He is bristling with passion and energy. And the world have mercy on anyone who tries to get in his way. And on the monster. And on the rest of the cast.

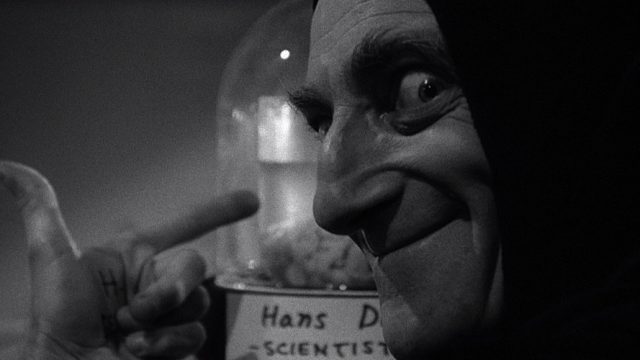

One of the great pleasures of Young Frankenstein is watching incredibly talented people firing on all cylinders. The script, by Wilder and director Mel Brooks, ranges from awful puns to surreal running jokes (I dare you to read “Frau Blucher” without hearing a horse neighing in your mind) to clever riffs on legacy, family, and the original Frankenstein movie. Visually, it’s an utter delight: shot in black and white to mimic James Whale’s iconic movies, the production even reused props from the 1931 classic and its sequel. Teri Garr is luminous (and busty). Madeline Kahn looks great, from her early “no touching” look to the Bride ‘do she sports later in the movie. Cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld, who also shot Sidney Lumet’s harrowing Fail-Safe and 1978’s Coma as part of a long career, makes everything look moody and beautiful.

The performances are what launch the movie into the stratosphere. Garr and Kahn are far more than pretty faces, and Cloris Leachman also has their crackerjack comic timing and enthusiasm for even the most absurd material. Peter Boyle, later to become a famous grump in Everybody Loves Raymond, is tall, imposing, and completely believable as someone who just woke up from the dead and isn’t too happy about it. Marty Feldman is the broadest character in the ensemble — his Igor often seems to have looked a few pages ahead in the script to make sure he liked what was going to happen next — but the movie is fast-paced and silly enough that his asides aren’t jarring. Even the minor roles allow actors like Gene Hackman to shine.

And of course, there’s Gene Wilder. Sometimes the calm at the center of the storm, usually the hurricane, young Victor Frank-un-STEEN’s journey from shame to his pride as a Frank-en-STEIN is the emotional heart of the movie, and Wilder sells it with every ounce of his manic energy and commitment. (How iconic is this performance? Wilder’s “It’s alive…it’s alive!” has been sampled in at least two pop songs, and when I was researching this piece, more than one writer said that Wilder is the “Frankenstein” they think of first.)

When I talk about parody and homage, I often refer to Howard Ashman’s words in the actor’s libretto for the Little Shop of Horrors musical:

Little Shop of Horrors satirizes many things: science fiction, “B” movies, musical comedy itself, and even the Faust legend. There will, therefore, be a temptation to play it for camp and low-comedy. This is a great and potentially fatal mistake. The script keeps its tongue firmly in its cheek, so the actors should not. Instead, they should play with simplicity, honesty — even when events are at their most outlandish.

Young Frankenstein plays it bigger and broader than Ashman recommended his actors perform in their B-movie homage. But the cast still throws itself into the work, sincerely and wholeheartedly. They might wink, but it’s a welcoming one, letting you in on the joke. There’s still simplicity and honesty here, just of a different sort. Some characters, like Leachman’s, never crack, putting the film as a whole on solid ground and providing balance to Feldman’s glorious mugging.

Young Frankenstein is my favorite Brooks movie, and I think one of the reasons is what a clear labor of love it is. He thought it was his best movie (though he didn’t think it was his funniest). Using the beats of the original canon, more or less, gives the movie an iron skeleton for the craziness to hang on, and he and Wilder complemented each other’s strengths incredibly well; when your collaborations are this and Blazing Saddles, you’ve got plenty to brag about. Why be normal, when you could make art like this instead?

Notes: “Sweet Mystery of Life” is from an actual operetta, Naughty Marietta. It debuted on Broadway in 1910 and was made into a Jeanette McDonald-Nelson Eddy vehicle in 1935.

Mental Floss has a fun list of trivia from the movie, and more pictures!