If everybody went to balls and did less drugs, it would be a fun world. (Dorian Corey)

Jennie Livingston’s Paris Is Burning belongs on my very short list of favorite documentaries; only Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control and maybe Powaqqatsi rank higher. Julius Kassendorf has noted the sheer density of information, context, and subject in 76 minutes of this film in his review; ten people could write this up and the resulting essays would have nothing in common but the movie itself. (Why yes, every other Solute writer, that was a challenge. Get going!) There’s no question that Paris Is Burning makes some fundamental challenges to conventions of sexuality, but I think it goes farther than that. It challenges a cornerstone of our way of life, the Enlightenment idea of the autonomous individual. It does a lot more, though; “challenging” has been a buzzword of critical discourse for roughly the last century, and I’m not much interested in it. Paris Is Burning doesn’t just challenge, it replaces that ideal of the individual with an idea and a practice of community that’s both something new and something very old.

Nearly the first line in Paris Is Burning comes from Pepper Labeija: “Do you want me to say who I am and all that?” It’s a typically subtle, nearly invisible move from Livingston, tossing a deep question about identity at us in what sounds like a throwaway line. Paris Is Burning covers the ball scene in New York at the end of the 1980s, interviewing and portraying its participants, judges, houses, families, rituals, language, and history. At the balls, people of color portray the fashion models, movie stars, soldiers, students, businesspeople, and celebrities of white society; it’s all judged with rigor and with enthusiasm. The participants aren’t heterosexual, but past that I would have a hard time categorizing them, because they include gay men, transsexuals, transvestites, and the question and challenge of identity goes all through this film.

Livingston’s method calls up Clifford Geertz’ “thick description”; she doesn’t shape the material here to an overall point, but to a sense of community in all its complexities and contradictions. (There are eight-hour miniseries that aren’t as informative or as fascinating as this.) She alternates between interviews with the characters and footage of the balls themselves; in technique, it doesn’t seem like anything special but that only means the technique doesn’t distract. It’s as well and subtly crafted as a Brakhage film: Livingston sometimes cuts from one interviewee saying one thing to the next one saying the opposite, giving the sense of the same community but different currents running through it. When she shows interviews with single people, there are almost always others in the background or off to the side of the frame, hanging out, watching TV, another way she shows community without ever stating it. Another technique here, one only apparent on rewatching: we often see the interview subjects in the balls or in the background before we see the interview, so they’re both stars of the documentary and members of the community. She uses split frames and busy backgrounds to keep the sense of energy going; she also shows a lot of people working while they talk, putting on makeup or sewing clothes. And Cheryl Lynn’s disco classic “Got to Be Real” keeps coming in on the soundtrack as a thematic refrain, too.

Another element contributes to the descriptive, discursive power of Paris Is Burning by its absence: there are no Talking Heads of Authority here to explain anything, not even a narrator. She avoids the Enlightenment-derived academic discourse that so many documentaries have, where the subjects exist to support the statements of someone in a book-lined office. No one speaks unless they’re part of the community, and there’s no attempt to draw any larger (i.e., outside the community) meaning from it–this isn’t a case study, but a world. Livingston does include a news report on voguing late in the film, which feels like the barest surface of the community that everyone outside of it sees.

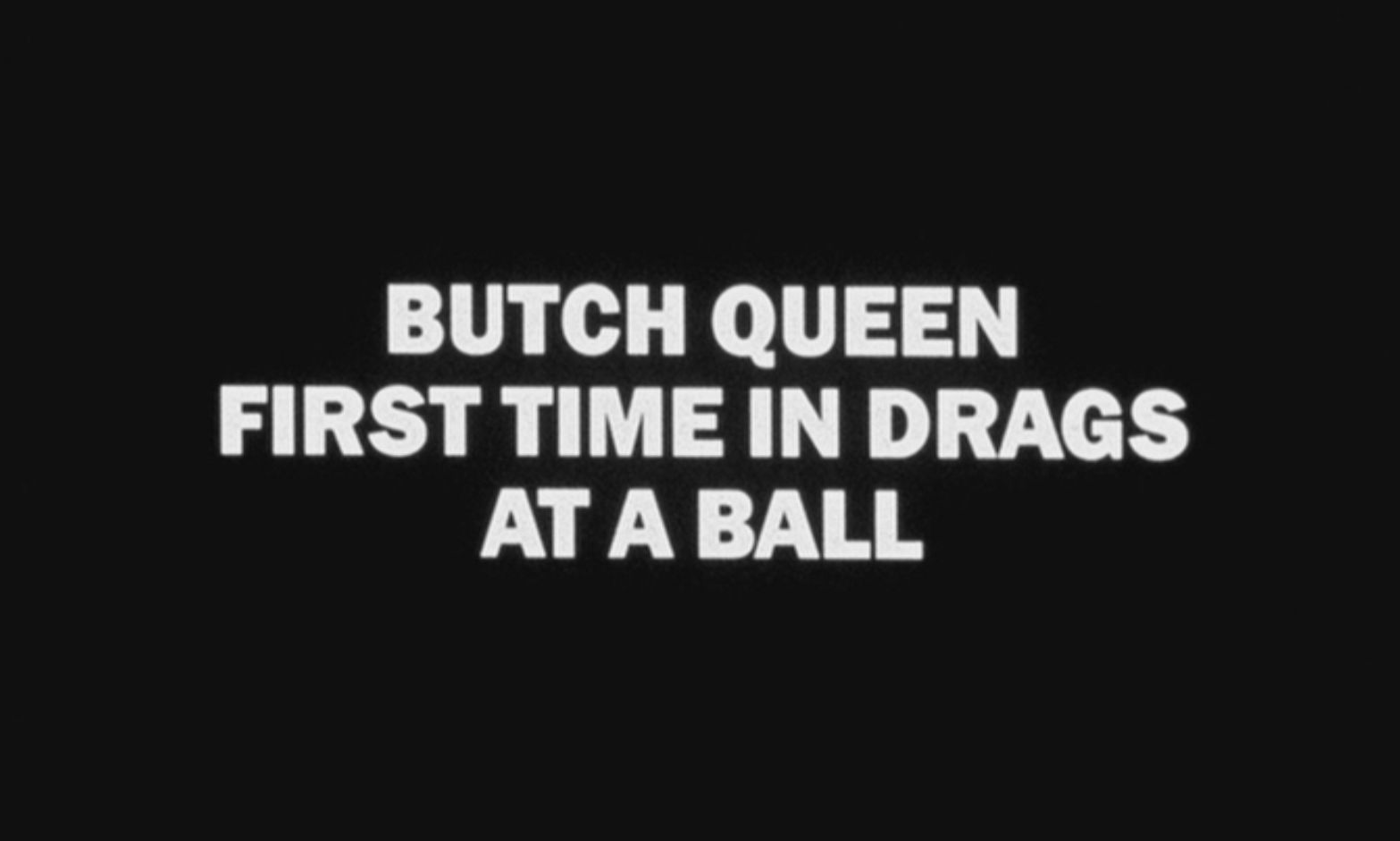

Livingston sometimes throws up block text on the screen in way that feels wonderfully 80s, the kind of thing Jenny Holzer did as art. (It also calls up the streamlined, blocky fashions that we sometimes see at the balls and often on the streets here.) Sometimes they’re names; in a more conventional documentary, these names would appear as captions. Making the names big like that and giving them their own screen gives the names a larger power and fame, turning the subjects into icons. A good definition of “icon” is a person who has become a concept, and some of the words are concepts spoken by characters (HOUSE, SHADE, MOTHER) that they will then explain to us–the three minutes on the Meaning of Shade make a perfect short subject/public service announcement. During the balls, we get a few of the categories displayed like this, making this less a documentary about the balls than a broadcast of them, like watching the Olympics. Categories include LUSCIOUS BODY, SCHOOLBOY/SCHOOLGIRL REALNESS, TOWN AND COUNTRY, EXECUTIVE REALNESS, and  which gives you a pretty good idea of the self-referentiality and history on display. It’s one of many laugh-way-out-loud moments; Paris Is Burning displays so much funny without ever laughing at its subjects and still holds to the most important questions. (So does Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control.)

which gives you a pretty good idea of the self-referentiality and history on display. It’s one of many laugh-way-out-loud moments; Paris Is Burning displays so much funny without ever laughing at its subjects and still holds to the most important questions. (So does Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control.)

People are judged in the balls, but that doesn’t mean they’re loved any less. Near the beginning, an MC (who provides commentary all through the movie) announces

please realize we all, at one time or another, have lusted to walk a ballroom floor. So give the patrons and the contestants, you know, a round of applause for nerve. ‘Cause with y’all vicious motherfuckers it do take nerve. Believe me, we’re not going to be shady, just fierce.

Judging is as essential to the community as love: it’s what drives people to adorn themselves better, to work at being part of the community. Without judging, there wouldn’t be the detailed work of making costumes, getting the walk right (at one point we see one of the contestants, Willi Ninja, training a class of young women in walking), of shade. There’s no sense here of everyone-is-created-equal. (In a declaration of American community older than the Declaration of Independence by over 150 years, John Winthrop stated that God had made the world unequal “so that every man might have need of another.”) Judging drives people to do better and also creates the sense of history, meaning, and hierarchy that all communities have.

Communities are not collections of independent individuals. The Enlightenment model of a community of people “where every one of the members has quitted his natural power, resigned it up into the hands of the community,” was described by John Locke in his Second Treatise of Government, came to be embedded in the Declaration of Independence and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, and describes the origin of approximately zero actual communities. Communities come into being organically, throughout history, and they have their own hierarchy, codes, language, and organization. The highest level of organization in this community is that of the houses–Xtravaganza, Labeija, Ninja (“ninjas hit hard, they hit fast, an invisible assassin, and that’s what we are,” sez Willi.) They are named after enduring winners of competitions; houses, here, feel like dynasties, and among those dynasties there are families, explicitly named as such. Often one person gets named as the mother, the one with the most power, as Pepper sez. Because so many people here have been thrown out of their biological families, the families they have in the ball community become their true ones. They support each other (“I bought her her tits!”), recognize each other, occasionally fight with each other, because that’s what families do:

My birthday’ll come up, I’ll always get a birthday gift from Angie [mother of the House of Xtravaganza]; I won’t get one from my real mother. When I got thrown out of my house, Angie let me stay with her until I got myself together and I got working. She always fed me. She can be a pain in the ass sometimes, but I wouldn’t trade her in for any other mother.

The concept of the individual–that autonomous, rational, freely choosing creature—is a few hundred years old; families go back to before the speciation of humans. Families are our first connection to each other and to history. Each family has its own history, like villages or military regiments, and that’s part of the identity of its members. Venus Xtravaganza tells of meeting the founder of the House, Hector, when she first came to New York, how he introduced her to transvestites and bought her a birthday cake. That detail comes up in some other houses, and it reminds us that families do things as simple as celebrate birthdays. (Another detail that Livingston includes in a single shot, and it’s typical of the density here: Hector died in 1985 at the age of 25, something that tells you so much about being gay in the 1980s.) The people within the houses support each other and love each other, they have a history and a place within the larger community; all of these characteristics were the original meaning of oikos, household.

That sense of history comes across as so essential here. Livingston accomplishes something amazing: she conveys a deep sense of history without ever giving a detailed history of the balls and their community. Part of that is through the way her subjects talk about the past and as one of them says “how they came to the balls”; part of that is through the cluttered visuals of the balls, the dressing rooms, and homes here. Everyone brings their own history in, often just through how they look and speak. (Quentin Tarantino once said of great characters “the face is the backstory,” and Livingston found some great faces here.) The history also comes through in the language, with all its references to generations: old bulls, children, protégés, legends, young ones. Probably more than anything, the sense of history comes from the sheer density of information here, the way that Livingston never overtly shapes things to any kind of reductive point. To quote some other gay icons of the 1980s, it’s a lot like life.

As an American, it’s almost impossible for me to think of the ideas of community and individual without phrasing it as “community vs. individual”; so much of American–really, so many of Enlightenment–stories are about the conflict between the two, and there is none of that in Paris Is Burning. Here, people become true individuals, true people really, because of their community. “Whatever you want to be, you be” says one participant, and there isn’t a more succinct description of individualism than that; the balls are where through will and work one can “become what one is,” in Nietzsche’s phrase. That these individuals model themselves on the images of the dominant society makes no difference; in the words of another, “it’s not a take-off or a satire.” It’s REALNESS. Despite the Enlightenment ideal of a purely choosing individual, everyone who becomes an individual, within the balls or without, has a history and models themselves on others. We all assemble who we are from the world we live in and the world that was, which is why there’s such a thing as history. It’s just more explicit here: “the ballroom tells me I’m somebody.” You can become who you are because you are recognized by a community as who you are, acknowledged for it, cheered for it, where outside the balls they would be shrugged off as deviant or simply ignored or worse. Like Del Close’s description of improvisation, the balls are not a substitution or an approximation of life: they are life. Against classical liberal theory, they are a real community that produces real individuals.

Some people have interviews that go all through the film, and anchor it. Two of them usually appear alone, the oldest (Dorian Corey) and the youngest (Venus Xtravaganza) and both of them deserve to become icons. Livingston’s craft is at her subtlest and most touching here. During most interviews, Corey places on makeup, almost never looking at the camera, coming across as someone devoted to the craft, to the community, and also as someone of an earlier generation who knows that the past won’t be coming back, the closest thing Paris Is Burning has to an official narrator. There’s a sadness here that feels necessary, the sadness of a time about to pass. (Corey gives a quick, elegant sense of the history of the balls by saying how the ideal figures go from showgirls to movie stars to models.) Livingston shoots Corey from the chest upwards; the effect is like Roman sculpture, making Corey the senior Senator, at one point trying to quiet an argument at a ball over whether a fur coat is a man’s or a woman’s (“it buttons on the right side!”)

Livingston shoots Venus usually in full-body shots, alone on her bed at home and with more space around her. (That bedroom could be any teenage girl’s from the 1980s.) Her voice is breathy without being high (she’s mid-transition, and hopes to get a sex-change operation); she’s small, almost fragile, and she talks about how that affects her job as an escort. Her beauty calls up a the consumptive heroines of nineteenth-century literature and opera; Tom Wolfe can brag all he wants about he’s the modern Balzac, but if Balzac had written The Bonfire of the Vanities, he would have found a way to work in Venus. (So would Dickens and Zola.) Corey gives the sense of history in this community, and Venus gives the sense of hope:

I want a car, I want to be with the man I love, I want a nice home away from New York up the Peekskills or maybe in Florida where no one knows me. I want my sex change. I want to get married in church in white. I want to be a complete woman and I want to be a professional model behind cameras in a high-fashion world. I want this, this is what I want. And I’m gonna go for it.

By the way, Julius is quite right that Paris Is Burning blurs the distinction between cross-dressing and transgenderism; my read on this is simply that that distinction is blurry within the community of the balls. (Mothers can identify as male or female.) There doesn’t seem to be any reference to a distinction between the two at the balls; whenever it comes up, it’s among people talking at the beach, at home, at a store, but never at the balls. I don’t know whether to consider this a flaw or just a consequence of Livingston’s relentless focus; as Julius and I have both said, it must have been an insanely difficult task to edit this down to a jammed hour and a quarter.

Late in Paris Is Burning, Livingston shows a fashion call in New York, and we can immediately see how much less diverse it is than the world of the balls. It’s not a matter of skin color. In the balls, participants emulate the icons of (mostly) white heterosexual society, but they emulate different icons. Octavia Saint Laurent, who attends the call, has several pictures of the supermodels of the day on her bedroom walls and she describes how each one of them has a look, something unique to them. We get to see Octavia practice her own look in the balls, we see she has the look even on the streets; she uses her height to come across as a little uncertain, maybe even vulnerable, but still strong, Twiggy crossbred with Iman. At the fashion call, though, there’s little sense of uniqueness; the white society that’s supposed to be about individualism produces only a bunch of imitation Christys and Paulinas and Cindys, people angling to be commodities rather than individuals, let alone members of a community. Livingston’s skill here is so subtle, and so good: we often see Octavia wandering in the middle background, looking puzzled, like what weird shit is this? Watching her interview, she comes across as interesting and ambitious beyond the level of employment; later, watching her fashion shoot, we can see her craft and adjust her look with a photographer. (Octavia wants to become a fashion icon, and Livingston intercuts her monologue about that with Venus’.) After an hour showing us the way fashion can make identity, Livingston turns around and shows us the kind of fashion that can strip it away. The community that was born in an imitation of the world of fashion ends up giving it someone more unique and beautiful than anyone from that world, and that’s inspiring.

If there’s an essential difference here, it’s that the people at the balls are a genuine community, and the people at the fashion call are a labor resource. The community of Paris Is Burning follows Augustine’s description in The City of God: “an assemblage of reasonable beings bound together by a common agreement as to the objects of their love. . .in order to discover the character of any people, we only have to observe what they love.” What this community loves is the will-to-adorn, what Zora Neale Hurston considered to black counterpart to the white will-to-power. The values aren’t based on independence and choice but on what you can make yourself look like, on REALNESS. (Augustine would’ve called it essentia, recognizably the same thing.) The will-to-adorn goes far beyond clothing or makeup here: you’re not born real, you become real; look like something well enough and you can be that thing. This is not a community that will become powerful, or safe, or any of the things in classical liberal theory. Augustine rejected another idea, that communities were founded on justice, saying if that were true, the thousand years of Rome could not be a community. What binds them is the belief and the practice that “whatever you want to be, you be,” and in the community of the balls, that becomes true.

Hurston wrote during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and you can see the balls in Paris Is Burning in continuity with them, a community that came together in a gilded age and created a different way of life. It’s a community, in the 20s and the 80s, that depended on a particularly urban setting for both the density of population and for its ballrooms. Livingston has a great feel for the spaces of New York City, shooting at the beaches, the piers, and the Hudson River to give an active, bright contrast to all the interiors of the film. She shows us how this is a subculture moving among the everyday life of the city. Among everything else, Paris Is Burning is as defining a New York film as anything Spike Lee or Martin Scorsese ever made; Livingston opens with a piece of visual poetry, moving from a shot of the skyline and cutting until we’re in a street-level interview. It’s a moment that’s reminiscent of the final shots of Gangs of New York or the titles of 25th Hour.

Most of this film was shot in 1987; Livingston comes back for a brief coda in 1989. Willi Ninja has become successful in the straight-world sense as a fashion model, dancer and choreographer; the balls have become, in his words, “toned down from what they used to be”; and Venus Xtravaganza was killed, strangled and left dead in a hotel room. (I don’t have a younger sister, and I suspect my feelings about Venus are very much that of an older brother. Specifically, on hearing this, I was ready to destroy the entire Eastern Seaboard to kill the fucker who killed her.) Since Livingston stays within the community of the balls for almost the entire film, this is a hard, unarguable reminder of how marginal these lives are and how easily they can fall off the edge. That doesn’t just mean that these people can be killed so easily; it’s that even their deaths can become forgotten. Venus had been dead four days before her body was found, and it’s only because Angie Xtravaganza was called that she wasn’t cremated and abandoned. Families are the people who remember when you’re born and when you die; so are communities. The Enlightenment got people wrong, because no matter how much power or reason or choice people have, they still die, and it’s only the community that can give them life and meaning after they’re gone. In the last moments of the film, Dorian Corey reminds us that what makes you matter is that “a few people remember your name.”

And there, Paris Is Burning makes clear perhaps its most important theme. Of all the things we see here, the most powerful is its sense of community; not a community that explains anything to us, not a case study, but a community that lives for its own sake, that has its own history and culture and its own values, a true, organic community by Edmund Burke’s or Augustine’s definition. Neither of them could have imagined this community; probably both of them would have denounced it, which tells you just how strong that idea of community is, stronger than prejudice or time. Although no one states this community’s highest, guiding principle, I felt it at the end. “Whatever you want to be, you be” is great and true for each individual, but what matters more is the unspoken commandment to everyone else: see me as I am, remember me as I was.

There can be no higher principle for a community; given that we are social creatures, there can be no higher principle, period. Augustine’s insight was to understand God as the force of good and of existence, the being that was the source of Being, “the supreme existence.” Every member of the community of Paris Is Burning recognizes the Being of each other; that is why the community came together and stays together. There’s nothing abstract about this, it’s present in every ball, every interview, every moment on the street or on the beach, every family, every house, every gaze caught by Livingston’s camera. Everyone sees who everyone else truly is, the presence of God within each, the Being of each being, the REALNESS of another.

Another founding mistake of liberal, Enlightenment philosophy is that it ignores this question of Being. The Enlightenment model of the individual is the person free to choose, but this is an entirely abstract concept of a person. It has no history, no sexuality, no fashion, only reason, “stripped of every relation, in all the nakedness and solitude of metaphysical abstraction,” in Burke’s words. (Burke used nakedness and clothing as a guiding metaphor in Reflections on the Revolution in France, so it makes sense that he shows up in discussions of this and Marie Antoinette, as both understand clothing as a necessary component of identity.) This has proven to be a big problem for liberalism, which has an inherent model of “everyone is all the same” and then keeps discovering differences between people. This means that controversies over things like affirmative action and gender-based justice (for example) cannot be resolved in a system of liberal values, because such a system has to simultaneously see everyone as the same and as different. Look at the community of the balls, though: there, difference is assumed and the common principle is, again, the recognition and glorification of that difference, of that history, of that Being.

We do not choose our Being, nor is it assigned to us at birth through biology. Both approaches come from the Enlightenment, the first through the virtue of choice, the second through the practice of science, and neither fully understands our Being. In a way that’s most likely more complex than any explanation, our Being has its own life, growing as we do, evolving and changing with other things, the other beings and the environment around all. Call it growth or evolution, revelation or transformation, I don’t know; whatever the verb, it takes time, and it only comes to fullness when it’s recognized. The balls that led to Paris Is Burning derived from one of the oldest communal traditions: the puberty ceremony, the recognition that a child was now part of the community. Here, it’s a recognition that one has advanced in the journey to become what one is, has come to live his or her Being. That Being isn’t some kind of abstraction, but fully adorned, fully beautiful, fully performed, historical, and diverse: fully human.

The Enlightenment holds freedom as its highest virtue, and that been the basis of so much of our law and culture. And it’s a virtue that just plain sucks when it comes to any kind of discussion of community; this virtue leads to only one principle when it comes to society: leave each other alone. (Slightly dressed up, this becomes Kant’s principle of “the greatest possible human freedom in accordance with laws by which the freedom of each is to be made consistent with all the others.”) When Margaret Thatcher proclaimed “there is no such thing as society,” she was not doing anything except stating the logical conclusion of Enlightenment thinking, and the Thatcher/Reagan policies in place at the time Paris Is Burning was filmed put her words into practice: you’re on your own, everyone.

The transformation in social life created by LGBTQIA people has quite possibly been the greatest one of my lifetime, and it’s an organic transformation of society, one where the laws have followed, not led. On the level of individuals, it’s been a liberation, making people everywhere aware of dimensions and diversities to sexuality, love, and pleasure that they never would have otherwise known. Great as that liberation has been, the transformation on the level of community may turn out to be the bigger one. Watching Paris Is Burning and looking at the last generation, the eros has been so diverse and will only get more so (just the LGBTQIA initials tell us that) but the agapē has been remarkably unified, based on the practice of recognizing each other’s Being. However they identify their sexuality, race, gender, history, everyone in this community lives the need to recognize everyone else for what they are. Everyone recognizes the need to help each other and respect each other. The Enlightenment gives us the virtue of tolerance, which is simply another aspect of freedom, another way of saying “leave each other alone.” Recognition of another’s Being, though, is much more active, even imperative, and it may be this community’s most enduring legacy.

If you want to see Augustine’s City of God, look here, in the community of beings that honor each other’s Being, the presence of God within each, “that God may be all in all.” (1 Corinthians 15:28) At the time of Augustine, the Roman Empire was falling apart. It had lasted for about a thousand years; its beginning was over twice as far in the past as the Enlightenment is in our past. Christianity wasn’t just a new message or a new idea, but a new way of being and it was beginning to expand from a few communities outward; it was beginning to change the world. In her essay against The Danish Girl, which goes far beyond a mere review to an extraordinary affirmation of values and selfhood, Sally Jane Black has said that transgendered people are Messiahs; watching Paris Is Burning, I get what that means. They are avatars of a way of life that is as radical as Christianity once was, and will change our world at least as much as it did. They are hated at first, because those who change the world always are; they find life and their memories are kept in a few communities, like that of Paris Is Burning; and the day comes when everyone lives differently because of them. Looking at the changes in laws and norms about marriage and transgenderism in the last twenty years, it’s clear that the change has already begun. Paris Is Burning is one of the first Gospels (literally, the Good News) of the new way.

We are a community and that community is broken, and it will not be fixed only by law; that was an insight granted to Martin Luther King and the basis of his action. However badass the 14th Amendment is, however many rights the Federal government protects, we are not merely a collection of individuals. I believe, as Burke did, that society is more important than government and “manners are of greater importance than law.” Laws should be made, political action should be taken, but it will also be necessary for the community to change; we will not be healed by Law or by guns. Watching Paris Is Burning, I saw what the new community will look like. It will take as its first rule see me as I am, remember me as I was, the recognition of another’s Being, the recognition of the need we have for each other; it will be less free and more loving; it will no doubt lead to great things and awful things, as Christianity has, as the Enlightenment has, as all enormous social transformations have. It is, certainly, not inherently any crazier to base a community on agapē than on freedom; it may be less so, because people have been communal beings from the beginning of humanity, even before that. We are a community and that community is broken; in a nation so devoted to the individual, that should not surprise us. Nor should it surprise us that we will be healed by the people who were never allowed to be part of it.

The stone which the builders refused

Is become the head stone of the corner.

This is the Lord’s doing;

It is marvelous in our eyes. (Psalm 118)