. . .measuring

our exacting times with the few exact terms,

holding fast to many antique forms an age in ruins

made, holding forth new modes for old truths

told by old men, upholding spirit’s laws with laws of mortal dust.

(Quintus Ennius, Annales, ca. 180 BCE)

For several years, I have been drawn to classical thought and works. My upbringing was squarely in the scientific Enlightenment tradition, something as essential to me as religious, denominational faith is to others; it was the framework of my thinking, and no other was possible. My apprehension of classical thought has been first through aesthetics; The Shield (to give just one example) cannot be fully appreciated through modern terms.

My goal in this (very occasional) series will be to look at classical, often conservative philosophies through contemporary works and artists. (Standard disclaimer: the contemporary conservative movement has almost nothing to do with conservatism.) I do this, as always, first to further my own understanding of both. It’s the power and quite possibly the purpose of art to bring us into confrontation with what we cannot imagine; it’s my hope that these essays will rekindle a discussion of ideas that still have power, because declaring an idea to be outmoded is not the same as confronting it. (And as the old man of The Solute, who better to do it than me?) Even if these discussions result in rejecting these ideas–and some of them I do reject–we benefit from knowing why, from knowing what of the past we choose to leave in the past.

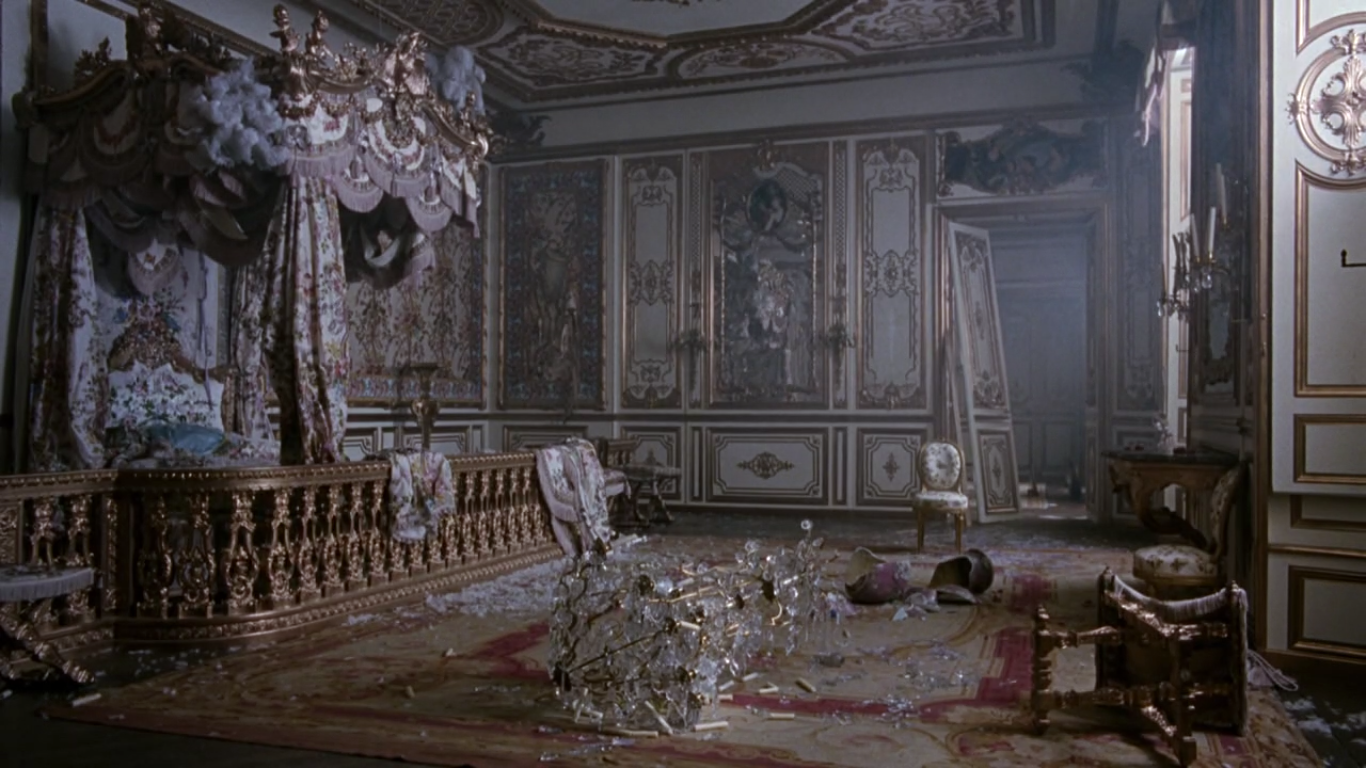

Sofia Coppola makes insular films about insulated people, and that makes her a distinctive and, for some, frustrating artist. She shows us the world of her characters, and as much as possible she shows it from the point of view of those characters, inevitably wealthy and privileged. She concedes nothing to any kind of external viewpoint or critique; it’s clear that her characters live in this world and understand it and for the most part, we don’t. Marie Antoinette succeeds more than any other of her works because it extends the insularity from the characters to the entire setting of the film; the end of the film isn’t just the end of Marie (Kirsten Dunst), it’s the end of a world. That world was the world of hierarchy, royalty, and privilege, the thing the French Revolution set out to destroy.

The Revolution’s “Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen” could stand as the founding document of our social morality, with its, well, declarations of rights of speech, of thought, worship, so forth, and the idea that one’s freedom should be unbounded (“Liberty consists in the freedom to do everything which injures no one else”) and that this freedom is the natural state of man. It’s the founding point of the union of liberty and rationality that characterizes the Age of the Enlightenment. It’s not surprising that the Revolution would seek to rewrite and rationalize the calendar, and declare 1792 (one year before Marie’s execution) to be Year One of the new republic. Conservatism really begins in response to the Revolution, and its founding document is Edmund Burke’s 1790 work Reflections on the Revolution in France. In opposition to the Declaration’s adherence to freedom and reason, Burke appealed to history, the order of society, and authority: “We are but too apt to consider things in the state in which we find them, without sufficiently adverting to the causes by which they have been produced and may possibly be upheld.”

Looking at freedom, for example, Burke argued that it should not be seen as a natural state of being but something specific, belonging to a nation, and attained through its history, “an entailed inheritance derived to us from our forefathers, and to be transmitted to our posterity.” As another example, look at the Declaration’s first right: “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good”; the conservative response is that social distinctions come from God, and they cannot be founded by Man. I’d add that the argument is equally strong, and in fact more conservative, if you replace “God” with “the past”–either way, social distinctions are there, and you don’t get to abolish them by vote or by violence.

(A quick digression–the fundamental weakness in conservatism is right there in the name: it can only deal with what is, not with what can be. Really, one doesn’t argue against conservatism. The world does that, rendering it obsolete by changing. The question “just how valuable is conservatism?” exactly becomes the question “just how much has the world not changed?” and the French Revolution did in fact change the world.)

Burke openly praised Marie Antoinette, and his old world is the world of Marie Antoinette, the world where the social hierarchy wasn’t just stable, but also righteous. Her characters never question their position, and Coppola doesn’t show us anyone who does. Dunst’s performance is so crucial here, because she never turns Marie into an oppressed woman. In a Coppola film, she crafts long passages where characters don’t do much, so Dunst has to convey things by posture and appearance; she inhabits her characters rather than animates them. She, Coppola, and Marie are a near-perfect union of actor, director, and character, especially for the Burkean way Coppola plays it. She concedes nothing to a contemporary feminist or class perspective, because both depend on the principle that men and women possess a freedom beyond their social roles. There’s never the post-Revolution sense that Marie has freedom born into her, and that freedom has been violated; nor is there the sense that she violated the freedom of the people of France. There’s only the sense that this is the role that’s been given to her, and she has to live with that, because everyone does.

Compare it to another movie about France’s social hierarchy, Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory. In Paths, that hierarchy was clearly outmoded and something worse than useless, represented by the kind but corrupt general played by Adolphe Menjou and the full-on evil one played George Macready. By 1916, that aristocracy didn’t serve any purpose and had degenerated into stupidity and careerism; but Coppola catches it at the last moment where it felt justified, where it felt natural, and showed it from within.

This film adapts Lady Antonia Fraser’s biography Marie Antoinette: the Journey, which organized her life into six parts and six identities. Coppola, like most great artists, makes a simple, effective choice here and sticks with it: she adapts only one part and one identity, Marie’s time at Versailles. The film begins with her journey from Austria to Versailles and ends when she leaves, driven out by the Paris mob. Coppola excises a huge amount of action and of Marie’s character, but she’s left with something essential: Marie as Queen. Coppola doesn’t show anything like “the real Marie Antoinette”–concern with the psychological reality of people belongs to our time, not Marie’s. (Fraser emphasizes that the real Marie was much more active than this one.) This is about what it means to live as a Queen, to live an identity that’s already been decided for you, and your identity doesn’t care how you feel about it.

Any doubts about Coppola’s talent should be put to rest by the first 30 minutes or so of Marie Antoinette (over a quarter of the whole). In addition scoring the opening to Gang of Four’s “Natural’s Not in It” (“The problem/of leisure/what to do/for pleasure”), she takes on and bests one of the most important tests for a director: crafting a sequence with minimal dialogue. This part of the film is slow, beautiful, setting us into the rhythm of the rest of it. Marie’s journey from Austria to Versailles has a lot of dead time and boredom (again, all Coppola’s films have that) and her arrival in France emphasizes how much “queen” was a change of being, not just title, as she has to go across the border literally naked. When she arrives at Versailles, the details of her life get laid out for us one by one, the rituals of dressing, eating, and displaying herself at court; Coppola has been accused of being obsessed with style as much as Spielberg of sentimentality, but here (as in A. I.) she shows us the cost of that, what it’s like to live your life in the gaze of an entire court, and by implication an entire country.

The movie covers over twenty years but not much happens. Marie goes to Versailles and becomes the bride of Louis 16 (Jason Schwartzman) and there’s an extended period when she doesn’t have sex with him. (Fraser discounts the long-held theory that Louis had the condition of phimosis, which makes erections extremely painful, and goes for the entirely plausible idea that neither Louis nor Marie knew what they were doing. Danny Huston, playing her brother, shows up later to explain things.) Louis becomes King, Marie has kids, she has an affair with Jamie Dornan (sadly, no todger here either), the French Revolution happens somewhere offscreen, and Louis and Marie leave Versailles.

That wouldn’t seem much to hang a movie on, but Coppola’s focus on Marie-as-Queen makes it work. Queens are images, not people, and life as an image is necessarily boring and static. Fraser’s Marie was a lot more active, but Coppola understands that Queens can’t actually do very much in this world; giving Marie more agency would make her fate more conventional, that of someone who tried to do something and failed. Marie Antoinette gives a sense of history that’s unique in movies, because it depends on literally external forces. The role of Queen disappears from this world, and nothing Marie did or could have done could change that.

As Marie, Dunst is in almost every scene; the movie’s gaze is as invasive and pitiless and France’s. Marie was 15 years old when she went to court and it’s impossible for Dunst to look it, and she wisely doesn’t try, but she can act it. She’s an unformed character at the beginning, without strong desires, but she tracks Marie’s growing maturity throughout. Jason Schwartzman’s Louis has the same quality and growth, going from early shallowness to something like depth; he acts like a king long enough that he becomes one. Coppola’s strategy here is a lot like Kubrick’s in that Marie (Louis too) gets defined by the spaces, clothes, and accessories; but Dunst by the end of the film shows a person has emerged from all of that and it gives her last moment so much power.

Visually, Marie Antoinette stuns; Coppola controls the image as fiercely as Kubrick did in Barry Lyndon (they share the same time period) but with a different approach to color. Barry Lyndon uses natural reds and browns and has its legendary candlelit interiors; Marie Antoinette goes for pastels, whites and yellows and pinks and stays mostly indoors; calling it candy-colored doesn’t go far enough for this marzipan-colored movie. Coppola creates long montages of things that can feel equally like we’ve landed in a shopping mall or a museum; it’s not just opulent but relentlessly so. Even more than The Wolf of Wall Street, wealth here comes off as confinement; when you combine that with the way Marie is always under gaze, Versailles becomes the most lush Panopticon ever made.

Coppola’s camera tracks well the spaces of Versailles, and how little privacy is to be found there; for about the first two-thirds of the film, Marie is either surrounded by people or completely alone; only late in the film, when she has her own retreat at Petit Trianon, do we see her with small groups. Perhaps the most affecting moment in the film comes when Marie, still childless, witnesses the birth of her nephew and realizes her stock has just crashed. She desperately has to find a private place to cry, and Coppola goes to a handheld camera and closes in on her face. It has the impact of the camera falling to the floor with Nicole Kidman in Eyes Wide Shut. Queens have privilege and wealth, but they have no privacy, and this is simply how the world is. There’s no sense of rage here, and no pity either; later, when Marie’s child dies, it’s done by a single cut to an altered painting. Even Barry Lyndon didn’t kill off his child that mercilessly.

A life of unearned privilege lived in the gaze of the populace is, of course, the life of a celebrity, and Coppola uses celebrity as the analogue to royalty. Simon Schama, in Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution, argues that an essential precursor to the French Revolution was the rise not just of newspapers but of a community of readers for them, and it’s easy to imagine Marie as the original subject of gossip; she protests about having never said “let them eat cake,” one more celebrity screwed over by whatever the 1789 equivalent of TMZ was. (It didn’t stop there; Fraser details many more unfounded rumors about her.) In only a few moments, Coppola lets us see the beginnings of a public image of Marie, but she keeps the subject of the film Marie at court. The formal climax of the film shows Marie bowing before the mob outside of Versailles, a neat image of the end of the old sovereignty and the birth of the ruler of the modern era, the People.

Coppola loads the film with a lot of recognizable faces–some (Steve Coogan, Marianne Faithful, Rip Torn) were recognizable in 2006, some (Tom Hardy, the aforementioned Jamie Dornan, Rose Byrne, Asia Argento) who have become more so. If it distracts from the period aspect of the film, it heightens the celebrity. And besides, they’re all so much damn fun–Torn continues his unbroken record of stealing any movie he’s in, Byrne gives her most enjoyable and least skinny performance (I suspect that’s not a coincidence), and Tom Hardy shows up. (You need more to sell that? I don’t.) Only Molly Shannon seems miscast, because she just can’t come off as anything but American.

Even without the cameos, Marie Antoinette swings well clear of a traditional period film because of its music. Beginning with Gang of Four in the titles (the design evokes the Sex Pistols), she builds a soundtrack largely from the post-punk era–the Cure, Adam and the Ants, Siouxsie and the Banshees, so forth. It further establishes the hybridization of royalty and celebrity, and becomes an essential part of the film’s whole aesthetic; the first and last shots of the film could easily be the front and back of a 1982 album cover. Bow Wow Wow’s “I Want Candy” for one of the montages-of-stuff (including candy, natch) may be the best-known song choice, but the most effective one is New Order’s “Ceremony,” the song that marked the transition from Joy Division to New Order, here (nearly all of it) used to mark the another transition: the coronation of Louis 16 and Marie’s birthday party, playing in the dawn afterwards. “Ceremony” (one of the most purely beautiful songs of the period), playing under the long shot of Marie and the guests watching the sun in silence at the end, makes them feel so much like any group of young royalty or celebrities, at any time.

Coppola’s latest movie, The Bling Ring (2013), serves as a contrast to Marie Antoinette, portraying a world of wealth and privilege without a social order to justify it, something else Burke warned about. Conservatives, unlike libertarians, have always been critical of capitalism, seeing it as the greatest source of change and destruction; Burke’s warning that France’s turn towards it would “turn its inhabitants into a nation of gamesters [and] make speculation as extensive as life” anticipates the Communist Manifesto by almost sixty years, and neatly describes the characters of The Bling Ring. One of the post-French Revolution ideals was “la carrière ouverte aux talents”–a career open to the talents, a world in which everyone could live up to their potential. Without talent, though, that openness becomes emptiness; without a social order, without social roles, freedom becomes floating, people connected to nothing at all.

That’s the world Coppola delineates in The Bling Ring. The teenagers here hang out together, but they barely seem friends; parents are largely absent (the first break-in happens at someone else’s home when the parents are away); there’s no romance here. There’s only the seeking of immediate pleasure (there’s not much sex here, because that would risk connection, but there’s a lot of drugs) and the pursuit of the one thing that has value in this world, celebrity. Early in the film, Marc (Israel Broussard) says “I’d like to have my own. . .lifestyle brand” and it’s the highest goal for anyone here, not to do anything but to turn your life into a label. Given that, breaking into the homes of celebrities and taking their stuff comes off as the logical next step of following them on Facebook. Marc comes off as the most touching of the bunch; he just moved into the neighborhood and has the least connection to anything, the least formed personality here and Broussard conveys that so well. He can never say no to anyone. When he’s dressing in the women’s clothing they stole, it doesn’t feel like transvestism; female celebrities get the most attention, so naturally that’s what he emulates, even in private.

The Bling Ring is beautiful, colored in primary pastels and sunshine (it was the last film shot by the great cinematographer Harris Savides) and dull, and that’s as necessary as in Marie Antoinette. As a film, everything happens in the first five minutes: Coppola goes from a break-in (more like a walk-in) to another montage of stuff (scored, here, to Sleigh Bells’ “Crown on the Ground”) intercut with the characters’ Facebook pages, and then to Emma Watson’s Nicki under arrest and speaking to reporters (while wearing some Jackie O sunglasses), saying “I want to lead a country one day, for all I know.” When we cut next to “One Year Earlier,” we have the essential beats of the next 85 minutes. These kids are as fated as Marie, but they’ll be nothing more than two weeks of interest online.

Watson, by the way, pulls a neat actor’s move here. She simply can’t disguise her intelligence onscreen (her face always concentrates), but here she changes it into an instinctive kind of cunning. This woman isn’t smart, but she’s forever looking at how to play the room she’s in, permanently ready for her close-up. (Marie couldn’t avoid the gaze of the populace; the characters of the The Bling Ring never stop pursuing it.) She also gets one spectacularly funny moment where her mom (Leslie Mann) keeps trying to upstage her in an interview, and she will have none of that thank you very much. It’s the kind of moment where actors seem to forge common DNA, and it shows that this is Nicki’s entire world, as much as Versailles was Marie’s.

Sofia Coppola was born into privilege, almost literally baptized into it (that’s her being baptized in The Godfather), and she will never leave it. If she gives one fuck that anyone has a problem with that, I haven’t seen any evidence in her films, and that’s really her greatest strength. Coppola understands the hierarchy of society that, despite the Declaration of Rights of Man and the Citizen’s first principle, still seems to be with us; saying Coppola doesn’t question the inequality of society implies that equality doesn’t need to be questioned. If I keep comparing her to Kubrick, it’s because they share a similar and perhaps defining principle: an unwillingness to concede their vision to someone else’s ideology. (Coppola’s self-confidence defines the difference between her and the filmmaker nearest to her in background and themes, Lena Dunham, who always seems to want us to like or at least understand her characters.) Marie Antoinette was really her ideal subject, and like Kubrick, she shows her life without sparing her feelings, or ours.

Inequality hasn’t gone away in our world, but it has lost its status as a virtue–and the French Revolution and the Declaration had a lot to do with that. In the near quarter-millennium since, inequality has changed its structure, largely because of the Industrial Revolution. When you combine the two revolutions, you live with the disconnect of an unequal society and a creed of equality. With Marie Antoinette and The Bling Ring, Coppola shows the difference between those inequalities, those privileges: at Versailles, inequality gave people an identity; in modern Beverly Hills, what you get are things and, if you’re lucky, fifteen minutes of fame. (Well, more like 50K likes of fame.)

I’ve often read critics who ask how we’re supposed to sympathize with Coppola’s privileged characters, and by the end of Marie Antoinette, I felt the answer: we shouldn’t. “Sympathy” is a virtue among the people of a society, but not a virtue between the ruled and the rulers. What I felt by the end of this film for Marie and Louis wasn’t sympathy, but respect and maybe even admiration, the Burkean virtue that the ruled should feel towards the rulers, just as judgment is the classical virtue rulers should feel toward the ruled. (Looking at The Bling Ring, I can almost sympathize with its lost children, but I could never respect them.) The virtue of respect acknowledges the impossibility of sympathy, because nothing will allow me to have these experiences or to know what they’re like; the distance between the classes is as great as the distance between our world and theirs. Respect may matter more than sympathy; it may be the most important social virtue across social classes, just as sympathy may be the most important virtue within them. (The challenge, possibly the deepest problem, of a democracy is that it asks the society to rule itself, and thus asks it to live the virtues of judgment and sympathy at the same time.)

In the penultimate moment of the film, you can see that Marie and Louis respect and admire each other too. They’re not lovers and they never were, but they’re the last two of their kind and they recognize it. Marie Antoinette unquestioningly and unapologetically shows the world of rigid classes, rigid wealth, and the justification of both at the moment it all came crashing down. In that final ride out of Versailles, when Marie says “I’m saying goodbye” and Coppola cuts to black and then into the final image of the film, it deserves as a caption the most famous lines from Burke, his elegy to her and to the past:

. . .little did I dream that I should have lived to see such disasters fallen upon her in a nation of gallant men, in a nation of men of honor and cavaliers. I thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her with insult. But the age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculators has succeeded; and the glory of Europe is extinguished forever.