Alexander Hamilton is my motherfucker. In 25 years of studying and teaching the story of America, I’ve found no Founder more valuable or more interesting. The least ideological, most practical of the bunch, Hamilton’s actions and his legacy were never about ideals, but about what was necessary, what one does to get a country going and to have it live. Washington’s assistant in the Revolution, the man who spearheaded the Federalist papers (the greatest work in all of political science, I have a copy on my bedside table. I assume all Americans do), the first Secretary of the Treasury and author of the Report on Manufactures (ignored when he wrote it because it was eighty years ahead of its time), Hamilton never cared about freedom or democracy except as means to an end: that America become a great, rich nation. And although Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit Hamilton: an American Musical doesn’t deeply examine Hamilton’s political philosophy (nor should it), it enlivens that philosophy in a vital, deeply American character.

That character has been a mainstay of American fiction, from Melville’s Ishmael to Fitzgerald’s Gatsby to Matthew Weiner’s Don Draper: the young man on the rise, the one who rejects his past in order to make his future and possibly his country’s through nothing more than sheer force of will. Hamilton makes Hamilton this character from the first song, starting with his arrival in New York in 1776. Like his brothers in fiction, he carries a sense of his destiny with him, works his ass off (“How do you write like tomorrow won’t arrive?/How do you write like you need it to survive?”–as someone who’s occasionally had to hack through his collected writings, I appreciate that line), has a lot of personal charm (I mean, look at your $10 bill. Dude was handsome, and Miranda sings him with a wonderful combination of dorkiness and self-confidence), and works his way up by the people he knows: Aaron Burr, Lafayette, George Washington.

My heroes have always been like that, ambitious, arrogant, out for themselves, and they made the world we live in: Hamilton, Machiavelli, Galileo, James Watson. None of them are necessarily good people (Watson is a straight-up asshole, always has been) because this kind of heroism, this kind of greatness, isn’t goodness; Machiavelli called it virtù, and that’s not the same thing as virtue–a hero is not a saint. Probably virility, broadly defined, is the best translation of virtù, the strength and power of creation and the thing that opposes fortuna. Ralph Waldo Emerson recognizably picks up on this idea in his description of the hero and how heroes change the world:

Heroism works in contradiction to the voice of mankind and in contradiction, for a time, to the voice of the great and good. Heroism is an obedience to the secret impulse of an individual’s character. Now to no other man can its wisdom appear as it does to him, for every man must be supposed to see a little farther on his own proper path than any one else. Therefore just and wise men take umbrage at his act, until after some little time be past; then they see it to be in unison with their acts.

(If this sounds a bit like Nietzsche’s übermensch, that’s because Emerson was a yuuuuuuuge influence; ol’ Freddy was really Emerson with the fun chemically extracted.) Even courage, as widely understood, isn’t part of heroism: Galileo never found a patron he couldn’t suck up to and when he got in trouble with the Church, he made it as far as seeing the instruments of torture before he said “I am so outta here.” (Translation modified.) And then he used the rest of the life that he bought to keep to his “own proper path” and pretty much invented physics. All these heroes created a new world, and there is nothing in reason or judgment that can create; it comes as no surprise that heroes are unreasonable. When history rolled around to them, they acted and changed the world. Probably the archetype for these heroes is Mark’s Apostles, a bunch of whiny, squabbling fishermen, and when the moment came, they straightaway cast down their nets, and followed Him.

Miranda’s Hamilton fits Emerson’s description and my pantheon of heroes, and what he created with others was America. He was directly involved in the Revolution (as Washington’s right-hand man) and the building of American government (more shortly), and by taking this kind of American character and placing him at the founding of American history, Miranda broadens his virtues to America’s: “just like my country I’m young, scrappy, and hungry and I’m not throwing away my shot.” Michael Hirst and Shekar Kapur pulled this move in Elizabeth, taking the plot of The Godfather and setting it at the beginning of the early modern world, so Elizabeth’s transformation wasn’t just hers, it was the world’s. 1776 was another turning point (not just for America: James Watt’s steam engine and The Wealth of Nations both debuted in that year) and without any additional weight, Hamilton’s story becomes America’s.

Miranda, working from Ron Chernow’s unexciting but reliable biography, scales Hamilton’s life down and finds a good throughline: Hamilton arrives in America, joins the Revolution, courts and marries Eliza Schulyer (Phillipa Soo), works under Washington as the first Secretary of the Treasury, he has an affair and gets blackmailed over it (this scandal led to a newspaper describing him as “possessed by an abundance of fluids that no number of whores could draw off,” quite possibly my favorite insult not written by Joan Didion or Shakespeare. It’s the only thing that I wish Miranda had included), his son dies in a duel, Hamilton throws his support to Thomas Jefferson in the 1800 Presidential election, and himself dies in a duel with Aaron Burr (Leslie Odom, Jr.). He keeps to a traditional rise-and-fall plot and ornaments it with many great and memorable scenes, and even gets Washington’s Farewell Address to sing.

If Miranda couldn’t do the same for the rest of Hamilton’s writings, he still conveys what made him so extraordinary; who we see and hear in Hamilton can be found in Hamilton’s own words. In his political science, the first priority was always the effectiveness of the government; he was the classical counter to Jefferson, who (deriving his ideas from John Locke), began with the purpose and justification of government. Hamilton’s first “axiom” isn’t as well known as Jefferson’s “to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,” but it should be; it has the same simplicity and force, and serves just as well as a first principle:

A government ought to contain in itself every power requisite to the full accomplishment of the objects committed to its care, and to the complete execution of trusts for which it is responsible; free from every other control, but a regard to the public good and to the sense of the people. (Federalist 31)

Hamilton always cared first about how to get things done, and more specifically how a government gets things done. (In the second song, Miranda has Hamilton talk about the need for a national fiscal policy.) It’s a theme he keeps coming back to in the Federalist, and in his role as Secretary of the Treasury: power, and how it may be most effectively used; how power may be properly used was a secondary concern at best to him: “the true test of a good government is its aptitude and tendency to produce a good administration.” (Federalist 69)

Underlying all the Federalists, and especially Hamilton’s, is the idea that the American government will allow its leaders to be the best possible. James Madison’s method, in Federalist 10, is the best known, “to refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens,” but Hamilton goes much further than that in his discussion of the executive branch and the need for a single President: “Decision, activity, secrecy, and dispatch will generally characterize the proceedings of one man, in a much more eminent degree, than the proceedings of any greater number; and in proportion as the number is increased, these qualities will be diminished.” (Federalist 70) (Fittingly, in the Federalist, the executive and judiciary branches of government are exclusively discussed by Hamilton, and the representative branch almost exclusively by Madison.) Hamilton further recognizes the action of committees and councils to slow down action and allow the blame to be spread to the point where no one is responsible (“In tenderness to individuals, I forbear to descend to particulars.”) For him, the President needs to be a heroic figure, someone able to act–to execute–and to solely bear the responsibility for that execution. This clears up a longstanding misreading of the Federalist and of American government: it’s designed to allow rule by the best, not to prevent rule by the worst.

As a political scientist, Hamilton was refreshingly devoid of ideology and morality; government’s purpose was to create and maintain a powerful nation, not be a demonstration of some theory (like the free market) or an example of goodness (as in John Winthrop’s “city on a hill.”) I suspect that’s part of the reason he’s been somewhat forgotten in American history: he can’t be associated with an event or a slogan. In Hamilton, after the Revolution, he sings “we studied and we fought and we killed/For the notion of a nation that we now get to build” and that does him justice. All through his writings, you can get the sense of “do what works,” and the understanding that “what works” changes over time. In Federalist 21, he argues against any “general or stationary rule, by which the ability of a State to pay taxes can be determined”; instead, “the national government [must] raise its own revenues in its own way. Imposts, excises, and in general all duties on articles of consumption may be compared to a fluid, which in time will find its level with the means of paying them.” (Fluids were a big deal to him, apparently; this was also a time when fluid mechanics was getting developed as a science.) Hamilton’s ideal of government was responsive, effective, and managerial, never more so than in 1791’s Report on Manufactures, entirely about setting free and managing the power of the just-begun Industrial Revolution. It was rejected at the time, and pretty much every single thing in it became true or was implemented in the century after he died; as in scb0212’s description of The Prince, “you can watch part of the modern world blossom from his pen.” That ability, as Emerson sez, to see a little farther than anyone else goes all through his work; if he’d been around in 1891 he would have written a Report on Consumption and John Maynard Keynes would use him as a reference.

Forever writing and constitutionally (and Constitutionally) unable to shut up from the first scene, Miranda’s Hamilton is just as obsessed with being effective, just as energetic, and just as in thrall to his own greatness as his writings are, what Eliza calls “the worlds you keep creating and erasing in your mind.” He can never lower his voice or silence his own opinions, and in the words of one of the songs, he’s never “Satisfied.” Aaron Burr, the eternal pragmatist and politician becomes his first mentor and counsels him to “talk less, smile more,” which he doesn’t. That’s followed with a spirited bar scene where Hamilton, Lafayette, Hercules Mulligan, and John Laurens drink some Sam Adams and get high on that spirit of ’76–the sense that they would all remake the world and “tell the story of tonight.” Really, the energy spreads from Hamilton to all of Hamilton; this is a wildly fun and fast musical, with Miranda piling on layers and choruses and characters and styles. (He also does well with repeated lines, and “who lives, who dies, who tells your story?” is the most effective.) As a genre, musicals do so well in expressing joy, and that picks up on a theme of Emerson’s: “what takes my fancy most in the heroic class is the good-humor and hilarity they exhibit” and that feeling goes all through Hamilton, never more so when Hamilton, Lafayette, and friends talk about the “LAAAAAAAAdies.”

Hamilton’s vision of government and society was clearly not one that held democracy as a virtue or a first principle. Democracy, rather, was a means to an end of the well-administered government, not the goal of government itself; I suspect he’d agree with one of the great conservative opinions, Churchill’s “democracy is the worst form of government, except for every other one that has been tried.” Hamilton follows this idea in that it’s not about the people but those who rule them, the ones in “The Room Where It Happened.”

Miranda has an unerring sense of the bonds between men; you can chart Hamilton’s voyage through this story by stations of friendship and rivalry. Burr begins as his mentor, and next up is General George Washington, given a suitably heroic entrance. Christopher Jackson plays Washington with an almost complete self-confidence (after all, in the war he’s “outgunned, outmanned, outnumbered, outplanned”) and he’s the one uncompromised hero of this story. He’s also the one character that genuinely awes Hamilton, and their friendship becomes nearly the most touching aspect here; when they duet on Washington’s Farewell Address, there’s both the sense of Hamilton losing his closest friend and the true ending of the Revolutionary era. Now the task of governing begins.

The true male second lead of Hamilton, correctly, is Thomas Jefferson. In a neat bit of structure, Miranda allows him to be mentioned at the beginning but keeps him offstage until the beginning of Act Two, coming in with the first song “What’d I Miss?” and has the same actor play him as Lafayette. In contrast to Miranda’s nervy performance, Daveed Diggs plays Jefferson with permanently engrained confidence, arrogance really, and flash. Hamilton’s Hamilton comes from the Ishmael-Gatsby-Draper lineage; its Jefferson derives from Porgy and Bess’ Sportin’ Life. He’s the Pimp, and having one of his first lines be “Sally be a lamb darlin’, won’tcha open it?” further drives that home, a great and disturbing moment. Jefferson becomes the first Secretary of State as Hamilton becomes the first Secretary of the Treasury, and Miranda stages a series of, well, Epic Rap Battles of History to begin the first great conflict of the new American government, between the Hamiltonians and the Jeffersonians.

Hamilton and Jefferson were on either side of the edge of the Enlightenment, Hamilton following the classical model of a government that needs to act, Jefferson proclaiming the new idea of a citizen with rights, “as against the government, the right to be let alone–the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men.” (Justice Louis Brandeis, 1928.) This conflict gets dramatized in Hamilton in arguments over the Federal government assuming the debts of the states, and whether or not America should aid the French Revolution: Jefferson argues that France helped America in its Revolution and the value of the people; Hamilton, of course, feels troubled by the absence of government “We signed a treaty with a King whose head is now in a basket/Would you like to take it out and ask it?/’Should we honor our treaty, King Louis’ head?’/’Uh, do whatever you want, I’m super dead’”–if you don’t hear the greatness of that line, I’m afraid Hamilton is just not for you.

The aristocratic Southern slaveowner became the champion of the people; the orphan immigrant became the darling of the New York financiers and the first manager of American power. That only seems like a contradiction if you believe those in the past are defined by the ideologies of the present, and Miranda never makes that mistake. He allows you to see the more complex relation between personality and ideology: Jefferson’s complete security in his position allows him to be generous to everyone else, like a benevolent prince; and Hamilton’s mad scramble for power convinces him that only those like him should have it. The split between the two would lead to the creation of the first two political parties in America: the Federalists, followers of Hamilton, advocating a strong central government and largely a party of the wealthy; and the Republicans (later the Democrat-Republicans, later the Democrats, yes it’s confusing), followers of Jefferson, the party of limited government and small landowners. A key breaking point was the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791, briefly alluded to in Hamilton, where Washington, at Hamilton’s urging, put down an uprising of Pennsylvania farmers over taxes on whiskey; Hamilton was pretty much demonized by the Jeffersonians after that. From the Revolution to the Civil War, American politics can be neatly described as “Hamiltonian means to Jeffersonian ends”; the success of Jefferson’s kind of people entirely depended on expansion of territory, roads, canals, and railroads within it, and a stabilized national economy, all things created by strong governments. Arguably, it’s still going on; Americans don’t mind depending on government as long as they don’t have to acknowledge they’re doing it.

Part of Miranda’s accomplishment here is to turn the ideas and conflicts of history into living, breathing, arguing, fucking human beings. That’s what epics have done since Gilgamesh: if an icon is a person who embodies a concept, an origin story has the job of turning these concepts back into people. Miranda is so generous on this point and in both directions: giving time and solos to so many characters who are not Hamilton, and letting those characters show their respect for him. For example, he has the excellent insight that Hamilton could respect the idealist Jefferson as he could never respect the ever-tacking-and-trimming Burr, and that’s what leads to Hamilton throwing his support to Jefferson in “The Election of 1800,” and the final Hamilton/Burr duel. All the major characters get a moment to pay their respects to Hamilton in the final song, “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story?” and Jefferson’s is perfect: “His financial system is a work of genius. I couldn’t undo it if I tried. . .and I tried.” Burr, all the way through, comes off as sympathetic, simply not possessed of the fire of heroism that Hamilton is, and realizing after the duel that he’s alive, yes, but now and forever the villain of the story.

Miranda often tosses from one character’s perspective to another in the same song. That allows him to bring in characters who get written out of history (again, who tells your story?) like Angelica Schulyer (Renée Elise Goldsberry), just as much in love with Hamilton as Eliza and just as smart as she is. Miranda brings women into this story in a way that they’ve been ignored, from the introduction of “The Schuyler Sisters” to Hamilton’s mistress Maria Reynolds to that one-off line with Sally Hemings. It’s usually stunning (Goldsberry brings down the house Supremes-style with “Satisfied”) and only occasionally clumsy on Eliza’s line “I’m writing myself out of the narrative,” which is too on-the-nose and worse, doesn’t sing well. Any mistake gets forgiven, though, by giving “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story?” to Eliza and letting her close out the evening. In these last minutes, she claims herself as part of the American story; the song shows rather than tells, and it shows that Eliza became as much of a hero as Hamilton. (I won’t reveal it, it’s too perfect an ending. I assure you that my crying was of a very virtù-like kind.)

Our heroes were those with vast talent and audacity, and no respect. (David Mamet)

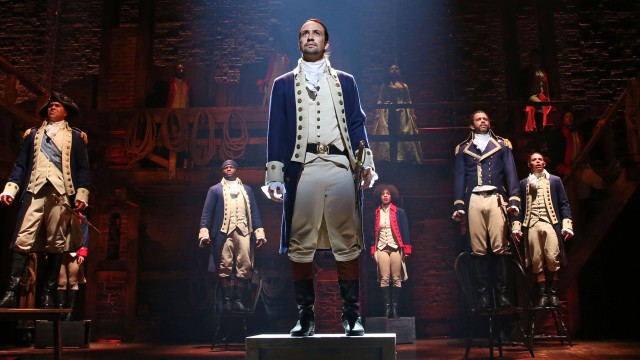

By now, anyone who has seen or heard Hamilton or has the slightest familiarity with it (like looking at that header image) will be wondering: why have I skipped over what’s so unique about it, that this story of the Founding Fathers is told in rap, in doo-wop, with references to “Summer in the City” and “The Message” and “Ten Crack Commandments” and by an almost entirely non-white cast? (Currently, the only definitively white actor is Rory O’Malley as King George.) Simply because from about twenty seconds in, I didn’t even notice. What Miranda and company do here comes off as natural as the Coen Bros. setting the Odyssey in Depression-era Louisiana in O Brother, Where Art Thou? and to the same effect: they take it, and make it their own. Hip-hop has been for so long a genre of much more than self-promotion; it’s been a musical place of self-assertion, of people demanding to be recognized as they are, and some of them even succeed at it. Miranda writes early America as the same kind of place. The term “cultural appropriation” gets a bad reputation, because it usually means those in power taking something from those not in power, but it can go the other way and that’s what Miranda and the Coens do. Like a great cover version, they make something that becomes its own origin.

Miranda created a new origin story for America from the facts of the old one and the materials of our contemporary culture and a cast that looks like the America of now. It’s not an act of criticism, but of creation; he didn’t point out that the standard American history has been dominated by white men (which, thanks, I already knew that) but made a new story with a cast of color as if the old one never existed. Thomas Carlyle noted that the great creators make something new unconsciously, unaffectedly, as if the old was never there; and Miranda is a great creator. The subtitle tells us: this isn’t a hip-hop musical, this is An American Musical, this is Miranda’s claim over the legacy of every American. Hamilton does what Hamilton did: both built a country, because neither Hamilton nor Miranda would keep to their place. Really, both of them are examples of what may be the deepest version of the American story: steal anything that isn’t nailed down and make something great of it. It’s what makes us a great and terrifying nation, what made our science and our slavery, our art and our genocide. It’s what’s behind the myth of the frontier, the structure of the economy, and so much of our literature, from Moby-Dick to All the King’s Men to Mad Men, right down to Hamilton. In this story, Americans don’t theorize or moralize, they act and create and destroy so many people along the way, because only God has the privilege of creation without destruction. (Angelica warns Eliza “Be careful with that one, love/He will do what it takes to survive.”) The story hands a legacy to all of us: to make something good of the country we inherited. This is why, by the way, America’s true national anthem is Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song,” which would work just fine as Hamilton’s exit music.

It’s my faith as a storyteller that a country’s meaning belongs to its story; without it, we are only a collection of real estate and factories. Everyone who tells the story makes their own version of the characters; I have my own Hamilton, a reflection of my own ideals (a professional, because of course) just as Miranda has his. Facts are a great place to start for these stories, but not to end; the stories matter to us because we can see ourselves and our country in them, not because we can check the footnotes. The stories inspire us, give us our values; we may be stuck with the past but the new stories allow a new future to come into being. Hamilton is a new origin story, a communal ritual; just as now as in 1776, just as in Hamilton ’s audience as in “The Story of Tonight,” we gather together in celebration and in hope, and America is born again.