Then if any one at all is to have the privilege of lying, the rulers of the State should be the persons; and they, in their dealings either with enemies or with their own citizens, may be allowed to lie for the public good. But nobody else should meddle with anything of the kind. . . (Plato, The Republic)

You want to be fooled. (last line of The Prestige)

The common theme of Christopher Nolan’s films, certainly all his best films, is “men living in the world by extreme codes,” an idea something like the code of professionalism in Michael Mann’s films, but taken much farther. In many of the films, there’s a common aspect to these codes: these men are liars, yet they’re all liars within a particular ethical and cinematic framework, something that goes beyond self-interest. Lying in Nolan’s work isn’t about plot twists, or characters who reveal themselves to be something they’re not, curse their sudden but inevitable betrayal! Lying is part of the code of the characters and the code of the films. Nolan always provides great drama in his works (at varying levels of success in orchestrating it) and like all great dramas, they can be read as ethical parables. Lying in these films gets bound up with a particular kind of character, the man who can rule over himself and others.

Caution: if a Nolan movie gets mentioned (and everything but Following and Insomnia will be), there’s gonna be SPOILERS.

The lie of the State

The Dark Knight portrays, as classical drama does, the rulers of Gotham City. Until the end, there are no attempts to give Gotham’s citizens–the demos–any role in the story, unless it’s the outright embarrassing yell of “no more dead cops!” at the press conference. And even at the end, the citizens get represented by two leaders, Tiny Lister among the prisoners and Not Ray Stevenson (Doug Ballard) among the citizens. Both boats go through the motions of voting, but their actions are decided by a single person. Both people decide according to Socrates’ principle: better to suffer evil than to commit evil. To suffer evil costs, at most, one’s life; committing evil costs the soul, and Joker intends to destroy the soul of Gotham.

All these rulers are liars; all of them lie as a necessary part of the action. Harvey lies, surrendering himself as Batman; Bruce Wayne always lies about who he is; Lucius Fox lies to get a Bat-transponder into the tower; the guy from Hong Kong lies to move the money; the Joker lies about where Harvey and Rachel are. (It took me about three viewings to catch that one.) Perhaps the one truth-teller is the Wayne Enterprises whistleblower, who catches all the money that Bruce funnels into his Batcareer, and he barely matters to the action. Joshua Harto portrays him as an essentially weak man, someone motivated only by greed and who doesn’t think things through (Fox saying “and your intention is to blackmail this man?” is one of the comic high points), a selfish, irresponsible truth-teller in contrast to the liars who take responsibility for their city.

And of course, all the lies lead to the final, dramatic, necessary lie of the story: Batman will lie and take the murders Harvey Dent committed upon himself. All through the film, the language has been right out of comic books, direct, forceful, and one notch below real poetry, and Batman’s lines are exactly right. Let’s break them up as they would be by speech balloons:

Because sometimes. . .the truth isn’t good enough.

Sometimes. . .people deserve better than that.

They deserve to have their faith rewarded.

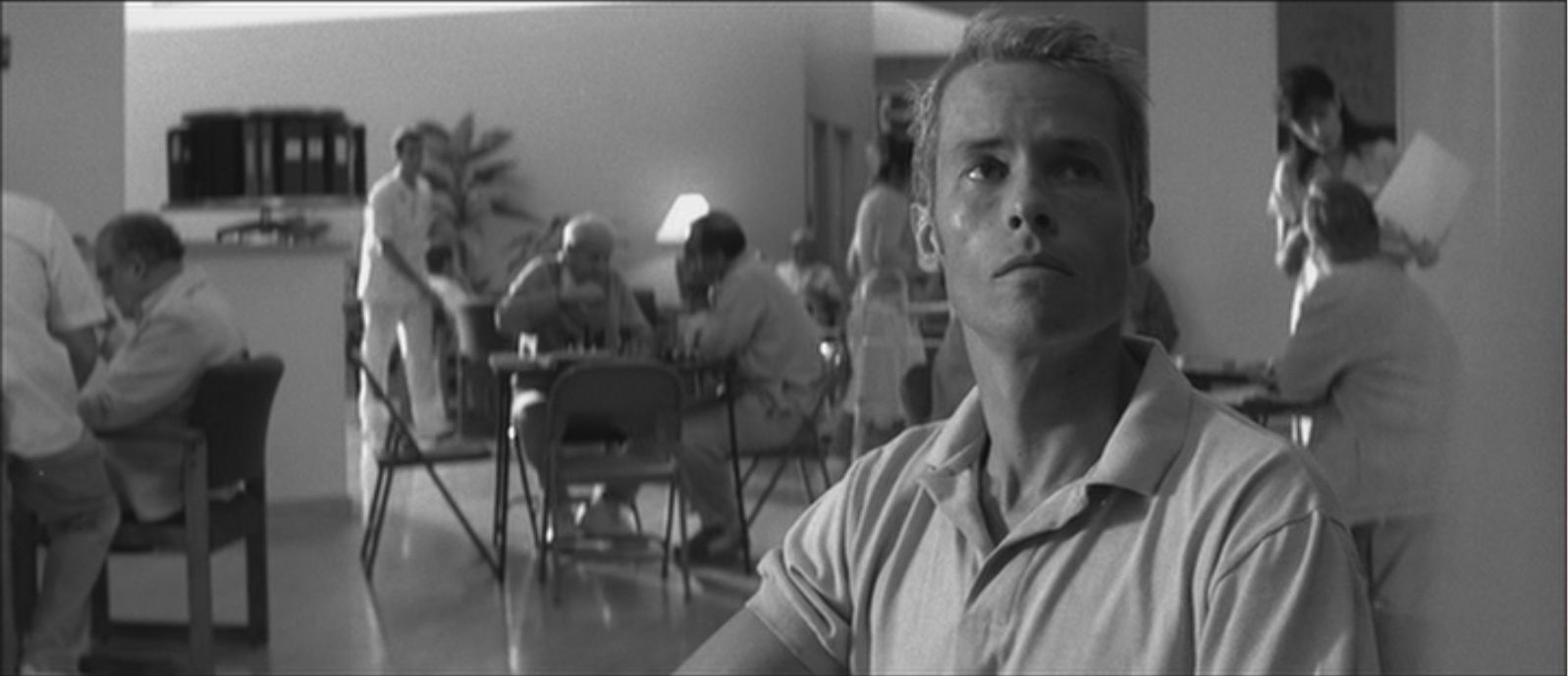

Batman will lie to preserve the ideal–or in Plato’s terms, the Form–of justice that’s represented by Harvey Dent. In Batman Begins, Ra’s al Ghul (Liam Neeson) tells the younger Bruce Wayne “if you dedicate yourself to an ideal, you become something more than a man” and that resonates all through The Dark Knight. Harvey Dent is one Form of justice, and Batman is another, and Nolan works this in many ways. The Form of Batman has his own Shadows in the hilarious touch of the imitation Batmen (no Form has ever worn hockey pads, let’s be clear) but more than that, Bruce Wayne struggles to live as a Form and that’s the dramatic line of his character (“Batman has no limits.” “Well you do, Master Wayne.”) Nolan also uses the looks of Christian Bale and Aaron Eckhart so well here–comics are a place where you can actually draw the Forms¹ and Bale and Eckhart both have the clean, improbable handsomeness of comic books, “project[ing] this extraordinary iconography from the inside” in their performances. And both of them are opposed by the Joker, “an agent of chaos,” someone with no agenda, who “just wants to watch the world burn.” That description is perfect–burning changes what has Form to ashes, to formlessness; the look Nolan and Heath Ledger crafted for the Joker works here too. Bale and Eckhart look like they’ve been drawn with edges, and Ledger seems to forever disintegrating.

Batman and Harvey Dent have to live their Forms, and both face the same challenge: what will you do for your city? The phrasing of that question assumes that people in cities have to be ruled: people do things for themselves but rulers do things for them. (Walter Lippmann said the problem with democracy was that it treated voting as the most important act in anyone’s life.) Batman’s final speech assumes that there are rulers and ruled, and the ruled don’t act, the rulers do. Because of that, the rulers owe something to the ruled. Lying, in the Republic and The Dark Knight, becomes a necessary act and a positive good. It becomes an act of sacrifice on Batman’s part to do this. Note that this lie is only possible because of the earlier lie about his identity; if Batman had been exposed as Bruce Wayne, he would be unable to take on Harvey Dent’s crimes. The smaller lies have necessarily led to the greater. The final moments echo Plato’s description of the good man from the Republic, where to be truly good, he has to live a lie:

. . . let us place the just man in his nobleness and simplicity, wishing, as Aeschylus says, to be and not to seem good. There must be no seeming, for if he seem to be just he will be honored and rewarded, and then we shall not know whether he is just for the sake of justice or for the sake of honors and rewards; therefore, let him be clothed in justice only, and have no other covering. . . . Let him be the best of men, and let him thought to be the worst; then he will have been put to the proof; and we shall see whether he will be affected by the fear of infamy and its consequences.

Two of the dominant institutions (maybe the most dominant) in the modern mind are capitalism and democracy; it was the combination of the two that Francis Fukuyama assured us had brought history to a close in 1991. (To his credit, he since acknowledged that he was, in a phrase, totally fucking wrong.) Both of these are mostly seen as mechanical systems that produce a good result, capitalism through purchase and democracy through voting, with the left placing its faith in democracy and the right in capitalism. By creating systems that translate the will of the people into action, we’re assured that we no longer need rulers; these are the mechanisms that will create self-rule.

The common belief, though, and the common weakness is that that these are systems, things that operate of their own accord without supervening action. Both, therefore, remove the need for any kind of sovereign action; indeed, those who believe in either system treat sovereign action as evil, because it interferes with the good-producing mechanisms. Again, the left denounces interference with the mechanisms of democracy and the right denounces the same action on capitalism. Continuing the symmetry: for the left, it’s capitalism that interferes with democracy; for the right, it’s government that interferes with capitalism. Whether these systems work well or not, I have yet to be convinced that self-rule is an inherent good; the phenomena of Donald Trump’s candidacy and disbelief in global warming probably leave you as unconvinced as I.

For that matter, I’m not sure that self-ruling systems are even possible. We have never seen a market nor a government that does not have rulers, that does not have a few people who make the decisions that affect everyone. Nor have I seen any market or a government that doesn’t need rulers, because events move too quickly and too unpredictably to be managed in any kind of mechanical way.² For the foreseeable future, then, we need to discuss the ethics of ruling, because not discussing how one rules well pretty much guarantees that one will rule badly.

Plato’s conception of ruling was not representative, but rather administrative, and a lie “is useful only as a medicine to men.” The ruler does what is best and what is necessary for the populace, not the will of the people, thus the logic of his doctor-patient metaphor. (The classical approach to ruling holds as a principle “first, do no harm.”) It can be necessary for the ruler to lie; in any case, it’s always necessary for the ruler to be separate from the people because the ruler exercises and must exercise only judgment, not empathy. At times, empathy becomes an absolute detriment to ruling–it is occasionally necessary for a government to fuck over its people, to fuck over some to help the many, or to fuck over the present to protect the future. (Striking down the Keystone XL pipeline is a good example of this: however many jobs it creates in the present, it’s not worth the damage to the future.) It’s another structural problem with self-rule, however expressed: someone can always gain power by saying “hey, the government just fucked you over.”

Nolan takes this idea of ruling, with doing harm and lying as necessary aspects of it, about as far as it can go in Interstellar. (He wrote this and several of these movies with his brother Jonathan, who has explored ideas of ruling and deception by rulers in his TV series Person of Interest.) As the last people on earth die, Michael Caine’s Dr. Brand (the Elder, to distinguish him from Anne Hathaway’s Dr. Brand) tells those trying to save them that they can be saved, that he will be able to develop an anti-gravity system in time to get everyone to another world before the oxygen and food run out. (Interstellar’s science is off at some key places but it’s mostly internally consistent.) That’s a lie; the system can’t be developed, “the equations can’t be solved”; all that can be done is to get enough frozen embryos to another world before everyone dies.

This element is one of those in which Interstellar fulfills Nolan’s ambitions, to dial things up to the level of 2001 and tell a story about an entire species and its evolution. Brand the Elder will allow everyone in the world to die, because he believes they cannot be saved; he will sacrifice the entire population to save the species, a sacrifice beyond anything Plato had the science to imagine. (He’s following a principle at a global scale that’s from the Republic. Plato recommended withholding some truths and stories from the people because “can any man be courageous who has the fear of death in him?”) Nolan doesn’t minimize the impact of that, giving Jessica Chastain’s incredibly expressive Murph the lines “you left us here. To suffocate, to starve.” Brand the Elder’s lie is in no way self-serving, it’s absolutely necessary; as Matt Damon’s Dr. Mann sez:

He knew how hard it would be to get people to work together to save the species instead of themselves, or their children. You never would have come here unless you believed you could save them. Evolution has yet to transcend that simple barrier. We can care deeply, selflessly, about those we know, but that empathy rarely extends beyond our line of sight.

Empathy only works–it only can work–for those we are truly close to, and empathy would lead only to despair. So Brand the Elder judged; he did the necessary and evil–“monstrous” as Brand the Younger calls it–thing by lying, a doctor telling a patient that he’ll be just fine so a last job can be finished. Think of a beautiful line in Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer: “I’m sworn to protect this sorry world, and that sometimes means doing what other people can’t.” So much of the modern, Enlightenment worldview depends on the axiom that humans are perfectible. Self-rule requires people to think and act “beyond our line of sight”; the classical view, the view of rulers, acknowledges that they don’t, because that is a limitation of humans. Arguably, that limitation defines humanity; Mann sez that Brand the Elder “sacrificed his humanity” with his lie. (Mann has his own, much more human lie; more on this later.) Rulers do not expect people to make decisions outside the scope of their lives. A self-ruling people cannot save itself from itself; rulers have to.

That Nolan, in crowd-pleasing form, allows the death of Earth’s population not to happen doesn’t minimize the impact of Brand the Elder’s decision. (Nolan made more than one decision to back away from the story and the science’s darker implications.) Interstellar may resolve in the happiest ending possible, but that choice remains the movie’s most memorable aspect for me.

The lie of cinema and photography is its actuality. We know words can deceive–in the line “I cannot tell a lie,” lies are told; much of the practice of criticism is about the question “is this author telling the truth?” Images deceive far more effectively, because we have to take them for reality. We see, and we come to conclusions based on what we see and what we already know–or what we think we know. And since we saw it, we become certain of that. That’s why we “want to be fooled,” and that’s not a weakness, that’s how our sense of sight has evolved to operate. (A species that sees an approaching tiger and wonders “huh, is that a tiger?” will not last long; in fact, it won’t last long enough to develop language and therefore the ability to lie.) For all the effects and grandiosity of The Dark Knight Rises, nothing lands as well as the reveal of Talia al Ghul. Take a shot of a child and tell me I’m seeing a boy, I have to see a boy; take the same shot and tell me I’m seeing a girl and I see a girl. Nolan relentlessly takes that weakness and spins it against us, but not as a joke on us, and not as a gimmick, but as a necessary part of his stories.

Images can lie to us because we construct a whole out of something literal but incomplete. Nolan bases all of Memento on that incompleteness. What Nolan called the “hairpin” structure of Memento, where the black-and-white scenes move forward and the color scenes move backward,³ becomes not a gimmick but essential. The black-and-white scenes are exposition and largely about what Leonard knew before his “condition,” so ordering isn’t important here. It’s not until the end of the film–really, when Leonard gets the picture under the door–that these sequences move into narrative. (The moment when Nolan shifts from black-and-white into color may be the subtlest visual trick of his career, and it took me three viewings to find it.) The color sequences run backward to deny us what Leonard can’t have: any memory of what he just did. Nolan lies by omission because Leonard does that to himself, all the time.

Because Leonard is an unreliable narrator, Memento is an unreliable narrative. We wind up questioning the basics of motivation–when we flash back to see Leonard’s wife is alive, what are we seeing? What’s real–what Leonard imagines, what Teddy is telling him? When we get just a few frames of Leonard in a mental hospital, we wonder, did he ever leave? What Leonard imagines can become real for him, it can become what we see, and that’s why Memento is so disturbing. The last thing we see is Leonard creating the reality of the story we just saw, as he sets himself up to go after Teddy. The film has been deceiving us because it’s been deceiving Leonard and he is the deceiver, the one who “simultaneously creates and perceives” his reality, to use Inception’s description of dreams.

Inception goes beyond Memento in that its lies take shape on the screen, not as a matter of a few flashbacks and not as omissions, but as entire stories. Also, these lies take the shape of totally cool PG-13 friendly blockbuster action sequences; Inception, better than any other Nolan film, balances his desire for big, thoughtful themes and cool shootouts and ‘splosions. Memento ends with the reveal that its world was at least in part Leonard’s imagination; Inception begins with that reveal, as Arthur says to Cobb “he knows.” Part of the sheer narrative fun of Inception comes not from figuring out that what we see is a dream, but wondering whose dream it is, and what truth the dream reveals.

Inception tells a story about storytelling, which is to say about lies that reveal the truth of its characters to themselves. And again, these truths-as-stories are there on the screen, whether it’s Cobb’s guilt in the form of Mal or Fisher’s fear in the form of his father’s last word being “disappointed.” (I only realized on the second viewing that Fisher’s father never actually said that; Fisher’s already dreaming when he tells that story.) Inception lies but it doesn’t deceive, and that allows its stories to have an emotional kick while we know they’re stories. Every damn time I see Fisher pull the pinwheel from the safe as his father dies, it just leaves me in tears (Cillian Murphy completely sells the moment); not only is it an artificial, constructed moment, there’s Tom Hardy’s Eames standing off to the side (and standing in for Nolan), giving that little smile because he knows it worked on Fisher (and Nolan knows it worked on us) and hitting the button and sending Inception into its full-BWAAAAAAAAMP quadruple climax, still one of the most deliriously joyful cinematic moments I’ve ever seen.

That Inception lies, even as it acknowledges the lies, make it impossible to find a single, unassailable interpretation of it. Most works that have characters lying or plot twists reveal the truth at the end. This is why I never get interested in films where Nothing Is as It Seems; my reaction is always “if I wait here long enough you’ll crack and tell me.” With Inception, we have to wonder if anything is as it seems; there’s no moment at the end where Nolan drops a Final Truth. He starts lying to us in the first scene, but when does he stop? Of course we leave the film before we can get the last answer, with the cut away from the spinning top. (Even if he showed what happened to the top, we wouldn’t believe him.) The most dreamlike aspect of Inception, much like Eyes Wide Shut, is the way that it generates multiple interpretations (one coming up shortly), and none of them work perfectly.

The sovereign self

In Memento, Nolan gives us a protagonist whose first lie is to himself. (It’s almost literally the first thing he does in the story, and almost literally the last thing we see him do.) Leonard loses control of himself and his self. His smartness, competency, inventiveness don’t matter; in fact, those qualities make his situation worse, because he’s as good at lying to himself as everything else he does. He becomes like a State cut off from its own history, not only repeating the mistakes of the past but making himself repeat those mistakes; Memento takes the form of classical tragedy stuck on infinite loop, with Leonard continually coming to recognition, creating a new situation, and starting over. (This observation is part of a discussion between myself, Rory the Lion, and thesplitsaber.) No one could be as free as Leonard, or as trapped. He is the perfect Enlightenment individual, smart, calculating, and free of any knowledge of the past and thus of any guilt. Leonard is a State with fantastic departments and a deluded sovereign, perfectly executing a deeply fucked-up mission.

Classically, the ideal of the self isn’t freedom–the absence of constraints–but sovereignty and control. The self was seen as a mess of passions that needed to be governed, just as a State was a mess of citizens that needed to be governed. This isn’t because passions or citizens are inherently bad, it’s that they’re not all inherently good, and given the opportunity, the bad will fuck up the good. As in The Dark Knight, there is no sense that the Self or the State will correct itself or regulate itself. There needs to be some kind of sovereign force to do both. The Dark Knight (and, to some extent, Batman Begins and The Dark Knight Rises) are about who will be the sovereign of Gotham City; compared with them, Memento is Nolan’s bleakest vision, the perpetual nightmare of the ungoverned self.

The need for self-sovereignty comes up in Interstellar too with Dr. Mann. He has created a massive lie too, that his planet is inhabitable–and by doing so, he might have doomed the entire human race, taking time and resources from the search for other planets. There’s no reason to do it except to give himself the hope of seeing another human being again, to no longer be more alone than any human being ever. (Of the first twelve astronauts sent to explore other worlds, Mann is the only one who survived.) As he says, no one has ever been tested as he was; what he did really wasn’t an act of cowardice, he simply broke and lost his sovereignty under a greater strain than any other person had known.

The difficulty of self-sovereignty is why I have to reject lying as a long-term political strategy. Leaving aside any moral questions (again, in some moralities, it’s a necessary good), it’s self-defeating. In both The Republic and 1984, Plato and Orwell imagined a ruling class that could be honest with itself and lie to everyone else, but it turns out that’s not possible: those who make their career out of lying start believing their own lies. There is no story from politics that left me as stunned as the report that in 2012 Mitt Romney’s team not only planned a victory celebration (complete with fireworks and a transition website) but they didn’t even write a concession speech. I’ve followed politics for forty years and I’ve never heard of anything like that. Whatever good lying creates gets quickly negated by the sheer incompetence it encourages. Only those who are truly sovereign over themselves can avoid this, and they’re in short supply; there are far more Leonard Shelbys than Bruce Waynes in the world, certainly in politics. Going back to the previous essay in this series, this is another problem when a democratic culture meets a hierarchical social structure: you get a ruling class that isn’t any good at ruling.

Inception takes this idea of self-sovereignty a step further: Leonard Shelby has lost control of his self, Cobb tries to regain control of his. Control of the self here extends to the subconscious; it’s necessary to do that if one wants to either keep secrets or create the dreamscapes that find secrets. Really, the central idea of Inception itself is about controlling one’s creativity–how do you know if your ideas are truly your own? Cobb emphasizes the creative part of our brains and also how that creativity can be hijacked. He describes to his pupil and dream-architect Ariadne (Ellen Page) the rules to avoid losing the distinction between dream and reality; we also see dreamers who never can leave the dream. Cobb’s own creative impulse has been largely taken over by Mal (Marion Cotillaird), the embodiment of his guilt over his wife’s suicide.⁴ The injunction to control one’s emotions has never been made so literal, so visual as in Inception; people who can control their own subconscious have “projections” that are armed with big, big guns.

I’ve noted before that although Michael Mann and Nolan explore men living by codes, Nolan’s are far more extreme. Mann grounds his codes in existing professions, extensively researches them, and trains his actors in them; Nolan creates alternate, extreme worlds for his extreme codes. What Nolan loses in realism he gains in imagination and spectacle, and it’s a fair trade–Nolan’s work is far more suited for summer blockbusters than Mann’s. (Except of course for the shit-ton of exposition needed to explain his worlds and codes, a practice my man Stu Willis calls Nolansplaining.) Still, a Michael Mann Dark Knight would be quite a thing to see (Nolan intended the opening as an homage to Heat), as would a Nolan version of Collateral.

The end of Inception leaves many possibilities open, the most obvious of which is that Cobb hasn’t regained control at all, but rather accepted his strongest (or, at least, most obvious) desire, to come back to his children. Another possibility is that this wasn’t Cobb’s inception, but an inception run on Cobb (most likely by Arthur) in order to get him to stop bringing Mal into the dreams. In this interpretation, Cobb went under sometime before the movie started, and wakes up on the plane. Several details support this reading, or at least throw other readings in question: Mal jumps off a balcony that’s nowhere near Cobb, which would mean that Cobb wouldn’t be accused of her murder and him being accused is just a paranoid fantasy; many of the action sequences come off with the same disregard for physics whether or not he’s dreaming, particularly the “collapsing walls” in Mumbai; and at the end, as Cobb gets off the plane, no one says anything to each other or really reacts–they could all have been strangers with which Cobb populated his dream. Only Arthur and Cobb share a look. In this reading, Arthur is Cobb’s secret sovereign, bringing him out of his destructive guilt over Mal’s suicide while all the while appearing to be the one with “no imagination,” every figure in the dream (i.e., every aspect of Cobb’s subconscious) underestimating him.

Nolan most fully realizes the themes of lying and sovereignty in The Prestige. That’s not surprising, for this film is to Nolan what Heat is to Michael Mann or Zodiac is to David Fincher, his most characteristic movie if not necessarily his best. Here, Nolan takes the theme of the sovereign liar about as far as it can go; he relentlessly demonstrates the phrase “your whole life is a lie.” The dueling magicians Alfred (Christian Bale) and Angier (Hugh Jackman) continually lie and deceive each other and everyone else, but in doing so, they have to give over their entire lives to the lie. In fact, they don’t just give over their lives to the lie, but both give their lives for it; by the end of The Prestige, Alfred dies once, and Angier has (in Amy Winehouse’s phrase) died a hundred times.

Nolan invokes this idea near the beginning, with Alfred and Angier watching a Chinese magician who fakes being handicapped for his magic; after the show Alfred says “this is the real performance,” where the man has to play handicapped at every moment of his life for the sake of the few moments when he’s onstage. That sets up what will happen throughout the film: Alfred and Angier both fake diaries for each other, disguise themselves for each other, deceive each other, but Alfred plays on another level. He already lives his life with a double, Fallon; they “take turns” being each other for the sake of a single illusion, the Transported Man. Alfred takes this all the way to his death: when he’s in prison, in one scene he easily slips his chains and puts them on a guard, making it clear that he could escape if he wanted to. He doesn’t; that would save his life but ruin the trick illusion.

Despite the fact that this twist gets foreshadowed to there’s-always-money-in-the-banana-stand levels, I missed it the first time through. However, I caught on right away to the Angier twist. Angier gets a machine from Nikola Tesla (David Bowie, adding one more to his roster of great performances of remote men) for his version of the Transported Man. It has a single flaw: it transports a copy of himself and leaves the original where it was. So, in a final run of 100 performances, Angier doubles himself every time and kills one of them. Every night, he has to walk into the machine with a 50/50 chance of dying, Russian roulette with three bullets in the revolver.

The performances reinforce this theme, visualizing it in a way other actors couldn’t. As Alfred’s wife Sarah, Rebecca Hall brings what Tarantino called naturalistic-as-hell acting; Hall is always so honest and direct in her actions that she sometimes destroys the balance of her films. She never feels like a minor character or plot point. Sarah simply isn’t capable of lying, or being lied to; she knows she’s living with half a person even if she can’t articulate that. Nolan’s cool style makes her suicide more effective; with Hall as Sarah, any directorial underlining would be too much. She already pushes the boundaries of our emotions. Bale is unsurprisingly great here, putting one more (OK, two more) portraits in his gallery of obsessives. It’s no insult to say this is a great technical performance, because the emotion of it (especially in contrast to Hall) comes from how Alfred and Fallon are always technically performing, and not always getting it right. Bale gives Alfred and Fallon slightly different characteristics, particularly speech patterns–on the second viewing (for some, on the first), it’s clear which one we’re seeing at any moment.

The surprise of the cast, for me, was Jackman. With Bale, Alfred and Fallon are ready from the beginning to go all the way, but the real story of The Prestige is how Angier learns that. Bale plays within his type but Jackman has to go against his. Jackman brings so much instinctive warmth in his performances; James Mangold used that well in Kate and Leopold, Darren Aronofsky used it even more in The Fountain, and Bryan Singer had to work against it for Wolverine. If you compare him against another Australian actor, Russell Crowe, his warmth becomes even clearer. That warmth, and the way Jackman plays against it, gives us a sense all through The Prestige of what Angier’s self-sovereignty costs him. Jackman gradually hardens the lines of his face; you can see, by the end of the story (and the beginning of the movie) when he steps into Tesla’s machine, the fear and the resolve. (Nolan makes this an inherently cinematic and duplicitous moment, with Jackman showing one face to the crowd and then another only to the camera.) You especially see the difference when Jackman’s playing Root, the undisciplined drunken double; it’s a much more fun performance and Jackman lets loose his stage-actor side for him. At the end, as Lord Caldlow, his face has hardened into a portrait, turning himself into a legend on a nightly basis, ready to become something more than a man. (As Lord Caldlow, Angier says “that is my real name,” which is interesting; he told his wife Julia at the beginning that he changed his name so his family wouldn’t know he’s a magician. Is he telling the truth here, at the end of the story?)

Something that a lot of filmmakers who have been both critical and commercial successes have in common is an ability, or perhaps a compulsion, to express their themes at different scales. (The Sugarland Express and Catch Me If You Can are recognizably the work of the same director; so are The Killing and The Shining.) Nolan’s theme of sovereignty, and way lies can destroy or reinforce that sovereignty works well whether it’s done across the three days and single city of Memento or the (at least) eighty years and (at least) two galaxies of Interstellar. It’s a great theme of drama, about what makes a character and how they interact with others, and it’s a great theme of cinema, confronting us with the distinction between what we see and what is. Nolan’s ambition makes me think he’ll keep pursuing this theme.

¹Joe McCulloch, in “The Avenging Page: in Excelsis Ditko” explores the idea of comics as expressing philosophical Forms in the later work of Steve Ditko. It’s one of the best and most inspiring pieces of criticism I’ve ever seen. Read it, like ten minutes ago.

²While writing this essay, I came across a piece by David Rieff in The Nation on the Gates Foundation’s charity work and how its practices were (to use a contemporary critical buzzword) “questionable” with respect to democracy. That’s not at all wrong, but what I found most interesting was that all the questioning was about the Foundation, with democracy assumed as an unquestioned good. (“This democracy deficit is the ghost at the banquet of philanthrocapitalism” felt like the thesis sentence, or at least something Rieff thought was pretty cool to say.) However, if it’s a foundation run by a zillionaire that’s unilaterally saving African lives and the democracies aren’t, that tells us something about the limits of democracy, including the limits of its moral worth. Rieff never mentioned this in the article.

³For a fuller discussion of the time sequencing of Nolan’s films, check out this most excellent essay by our own Michael G.

⁴Roger Zelazny explored the same idea–psychologists who created dreams for their patients, joined them in the dream, and what happens if they lost control–in the short story “He Who Shapes,” later expanded into the novel The Dream Master. To my knowledge, Nolan has never acknowledged this as a source. Pretty sure if Harlan Ellison had written it, the lawsuits would still be ongoing.