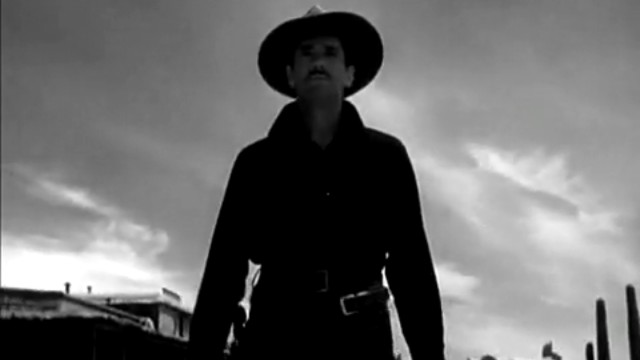

SCENE: A dusty cow-town. Our hero, an honest man despite sometimes being on the wrong side of the law, stiffens himself with a drink in the saloon. The noisy barroom grows quiet as he calmly strides to the door. Our hero steps through the doors with his gun. He is going to meet his fate.

American Director John Ford (1894-1973) certainly didn’t invent the Western or the iconic gunfight scene, but during his 54-year career he elevated a much-derided genre into an art form, creating an American myth that still resonates despite decades of imitation, deconstruction and parody.

The Criterion Collection released Tuesday a restored edition of My Darling Clementine (1946), one of Ford’s best Westerns and a seminal film in the post-World War II revival of the genre. This essay will examine Ford’s treatment of the Western Hero in Clementine and two of his other great films, Stagecoach (1939) and The Man who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). We will begin with Stagecoach, thought by many to be the first “serious” Western.

Warning: Spoilers for decades-old films are contained below

The Creation of the Western hero

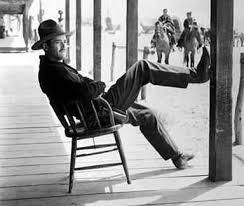

Stagecoach is essentially an ensemble piece, although The Ringo Kid (John Wayne) is the first among equals. The seven passengers making the treacherous journey from Arizona to New Mexico are all, in one form or another, heading to their fate; but it is the journey of The Kid, as he is known to the other characters, that most fascinates Ford.

The Kid doesn’t show up until about 20 minutes into the film, but he is a frequent topic of conversation even before his arrival. When he does arrive, as an escaped convict bent on avenging the death of his brother, he is given a show-stopping entrance. Ford did not frequently use attention-getting camera movements, but in this case he pulls out a doozy. The scene begins with a medium shot of Wayne twirling his gun and yelling “Whoa-O” to stop the Stagecoach as a process shot of Monument Valley plays behind him. Ford then moves the camera to a full close-up of Wayne’s youthful and handsome face (it can be surprising for modern audiences who are more used to the older, grizzled Wayne, to see just how good-looking he really was). This is such pure 1930s movie-star treatment (luminous close-ups were Garbo’s bread and butter) that audiences would have immediately known a new-kind of hero had arrived.

Once Wayne gets inside the stagecoach, he easily dominates the film. He doesn’t really get that much dialogue, but, as Peter Bogdanovich points out in the Criterion supplements, he gets a good deal of the reaction shots. This treatment essentially makes The Kid the moral center of the film. His judgments of the other characters become the audience’s judgments: thus we know that Doc Boone (Thomas Mitchell) is a good egg despite the fact that he like to hit the bottle and that the banker Gatewood (Berton Churchill) is a hypocritical blowhard.

Wayne and Ford portray The Kid as a gentle and naive man despite his thirst for vengeance. What The Kid really wants to do is settle down on his ranch and raise a family with his lady-love, Dallas (Claire Trevor, playing the definitive hooker with a heart of gold).

The climatic gunfight only takes up the last 10 minutes of the film and it is almost an afterthought, although an expertly staged, lit and photographed afterthought. Of course, our hero wins the day and rides off into the sunset (actually a sunrise) with Dallas, while The End flashes across the screen. In fact, for Ford, Wayne and the Western hero, it was just the beginning.

The myth of the Western hero

The gunfight is certainly not an afterthought in My Darling Clementine. Confrontation, or rather a series of confrontations both petty and life-altering, are at the heart of the film. Ford made this film seven years after Stagecoach and he scraps the ensemble drama of that film to focus on a lone man’s search for justice.

Clementine is very loosely based on the actual events of the gunfight at the OK Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, although most of the film is wildly inaccurate (even the date is wrong: the gunfight was not in 1882 as stated in the film, but in 1881). Ford’s interest wasn’t really in recreating history. Instead, he used the sweeping vistas of Monument Valley to create a mythic landscape for a Manichean epic of civilization versus lawlessness.

At the beginning of the film, Wyatt Earp (Henry Fonda) sweeps into Tombstone like an Old Testament prophet. He quickly takes the thankless job of US Marshal, basically because he wants to avenge the death of his brother, but also because no one else really want it. He immediately begins the arduous task of cleaning out the fleshpots of Tombstone, which Ford portrays as an arty version of hell, full of jostling crowds, gas lanterns and really, really annoying music.

Earp is an incorruptible paragon unable to be bought, bribed or seduced. As Doc Holliday (Victor Mature) wryly notes, Earp has come to Tombstone to “deliver us from all evil.” In fact, nothing is too small to escape the new marshal’s notice. Is there a card sharper in town? Not since Marshal Earp kicked them out of town. Is the Bon Ton Tonsorial Parlor overrun by criminal elements? Since Marshal Earp came to town you can get a shave and haircut without being molested. Earp is such a bad-ass he even manages to win a gunfight against Doc Holliday while not even having a gun.

All of this law and order soon brings out the upright, God-fearing citizens of Tombstone, who had presumably been cowering under their beds while the filthy sinners ran riot. They’re soon enjoying chicken dinners at the local restaurant and building a large church in the center of town. All that is left is for Earp to wipe out the last stubborn holdouts of unrighteousness at the OK Corral, before riding off into the sunset.

The Hero as a Fraud

By the time Ford made The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance in 1962, the incorruptible Western hero was a staple of both films (Shane, High Noon) and television (Gunsmoke, The Rifleman). Ford made more films after Valance, but in many ways this film is a valedictory statement, both a celebration of and a challenge to the myth of the Western Hero.

In Valance, Ford splits the Western hero into two characters: hardened rancher Tom Doniphon (Wayne) and naive lawyer Ransom “Ranse” Stoddard (James Stewart). The film begins with Stoddard, now a US Senator, returning to the frontier town of Shinbone, where he made his name many years before by killing the local outlaw, Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin). What really happened during that fateful gunfight is the film’s main concern, uncovering troubling questions about reality vs myth and the true nature of hero worship.

Stoddard has returned to town for Doniphon’s funeral and pesky questions from a young reporter (Joseph Hoover) lead to a series of Rashomon-like flashbacks that reveal a truth that is more complicated and ambiguous than the heroic myths that have surrounded Stoddard.

To put it plainly, Stoddard is a fraud. He did not kill Valance. He did go out to meet him for a gunfight, but Doniphon, firing from the shadows, was the real assassin. Stoddard does not realize this until months later, but he never publicly corrects the record. He becomes the great man at the statehouse and Washington DC, even marrying Doniphon’s girl, based on a myth that he had unknowingly created.

Ford never condemns Stoddard for his actions and Stoddard, played by the likable Stewart, maintains the audience’s sympathy. The film is more an elegy for the West and the way of life that was swept away by the forces of modern civilization. The era when a pure-hearted hero could clean out a cow-town with nothing but a six-shooter and his courage has passed. Now the West is full of locomotives and electric lights and nosy reporters wanting to know the “real” story.

The film ends on an ambiguous note. Stoddard does eventually tell the reporter and his editor the truth, but the editor (Carleton Young) rips up the story and utters the now iconic phrase, “Print the legend.” Stoddard then heads back to Washington. On the train,he is given first class treatment by railroad employees because “nothing’s too good for the man who shot Liberty Valance.” Meanwhile Tom Doniphon’s body lies back in the desert in a lonely grave.

Sources for this article are Print the Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford and John Wayne: The Life and Legend by Scott Eyman; The Star Machine by Jeanine Basinger and The Illustrated History Of Cinema edited by Ann Lloyd.

Stagecoach is available on Hulu Plus; The Man who Shot Liberty Valance is available on Netflix Instant.