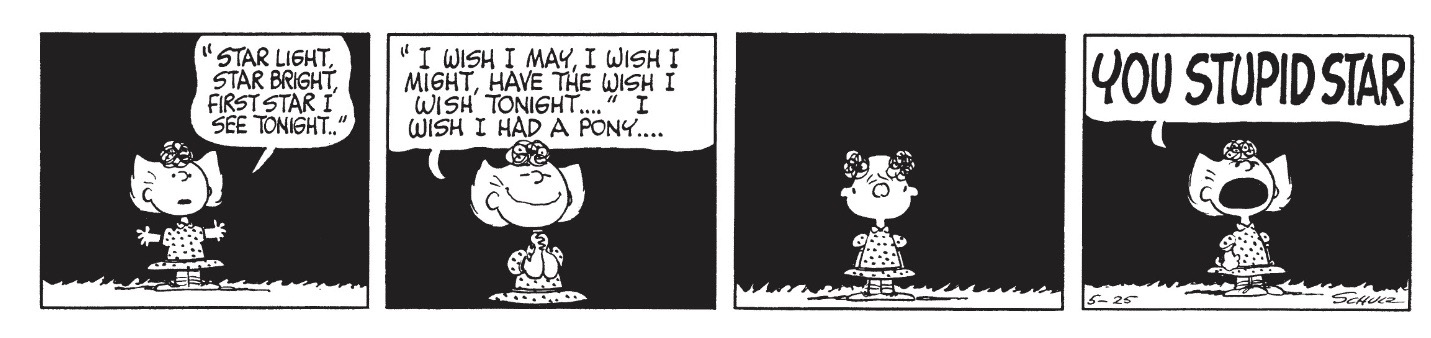

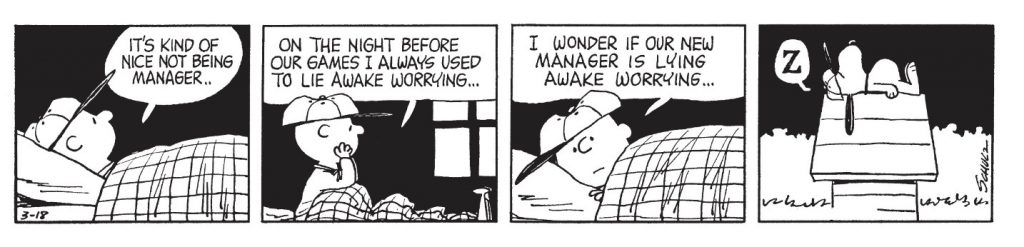

Years ago, my mom caught me revisiting our old tape of Snoopy Come Home. “This movie always used to make you so happy!” she said, which confused me deeply. How could something so sad have made my little self happy? But that’s really what makes Peanuts as great as it is. This little piece of newspaper filler captures the extremes of joy and sadness so well, better than a lot of so-called “high art.” It gives equal weight to both, but because we’re so unused to such an unsentimental depiction of childhood, it’s often reduced in the popular imagination to an unending parade of misery that had no business being sold to children. (In that way it’s similar to past Year of the Month subject The Seventh Seal, if for different reasons.) The two leads, Snoopy and Charlie Brown, do a nice job showing off this divide, especially in the strips from this month’s year, 1968. Compare the way they stay up at night wondering about life.

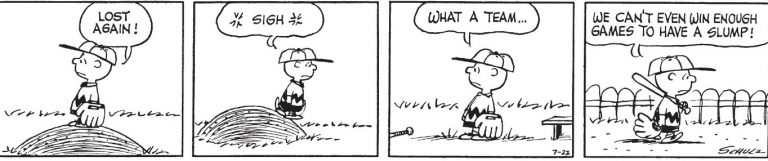

It’s a comparison Schulz makes explicit in a hilarious episode from the sequence where Snoopy takes over for his owner as manager of the baseball team.

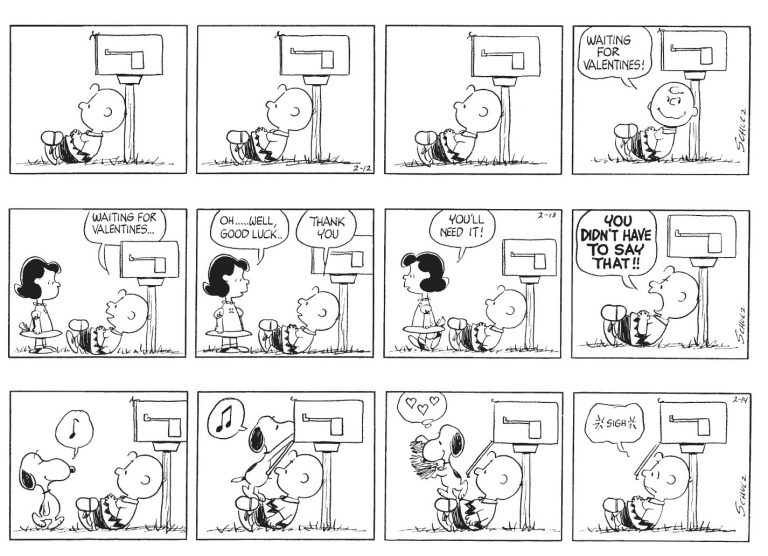

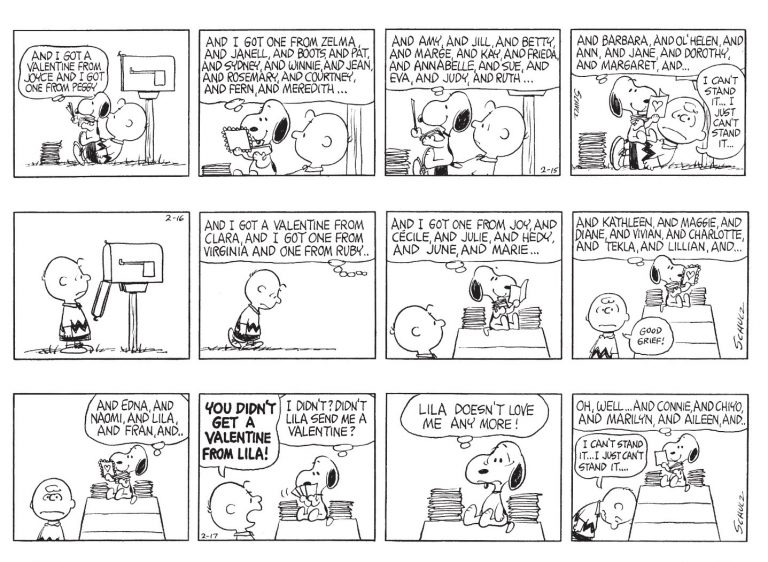

And there’s the iconic sequence of Charlie Brown “waiting for valentines,” in a wonderfully pure literalization of the human desire for affirmation:

And there’s the iconic sequence of Charlie Brown “waiting for valentines,” in a wonderfully pure literalization of the human desire for affirmation:

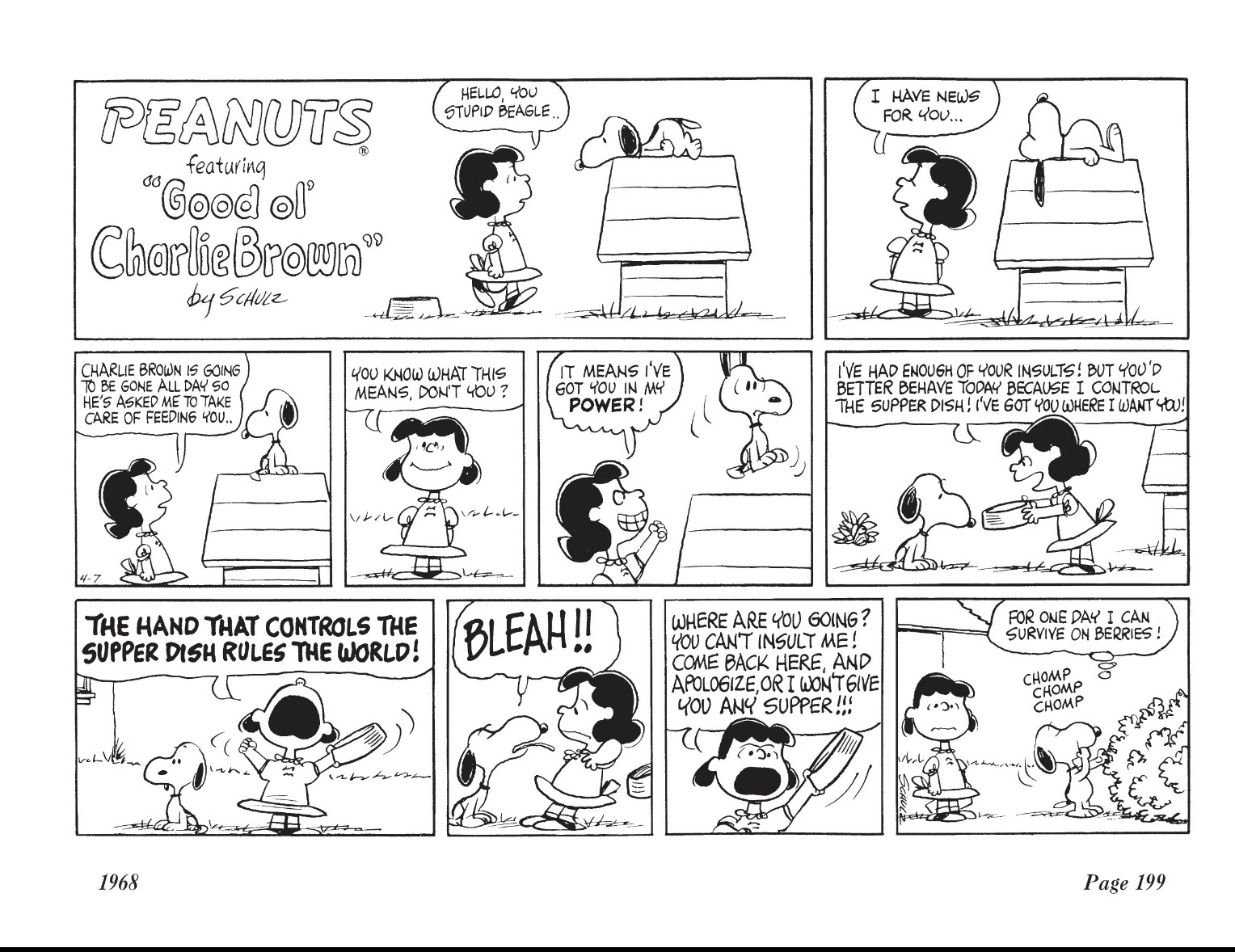

Even when Charlie Brown actively tries to being Snoopy down with him, he bounces back immediately. You could spend weeks debating whether Snoopy’s cheerfulness explains his popularity or the other way around, but Peanuts isn’t here as a guide to living so much as an observation of it. And even that might be too literal of an interpretation – Snoopy’s indefatigability is pure cartoon logic, and nothing, not Lucy

or even the laws of physics can stand in his way.

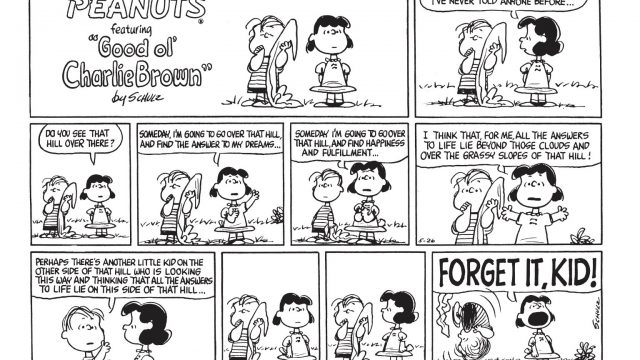

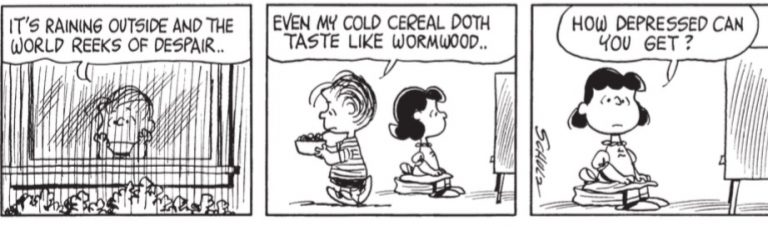

And just as Peanuts depends on bouncing these two opposites off of each other, the tragedy and comedy of the series are woven together. In the world of Peanuts, nothing in the world is funnier than misery. This isn’t to say Schulz is laughing at his characters either. He’s laughing with them and crying with them all at the same time, and inviting us to do the same thing. Sometimes their depression can be a little ridiculous…

And sometimes it’s obviously taken right from Schulz’s own soul…

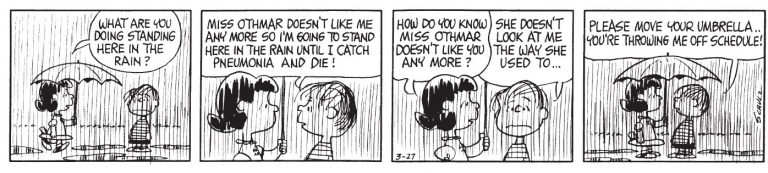

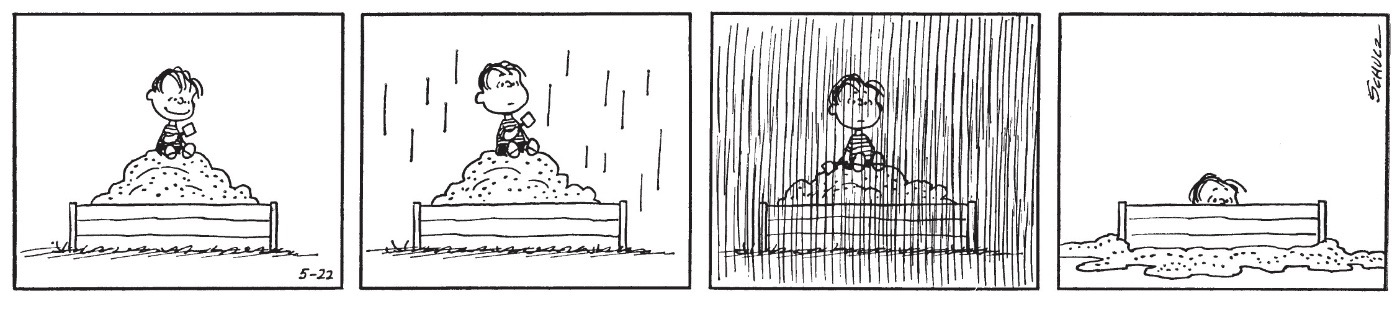

but he always finds the humor in it. 1968 featured an especially memorable sequence where Linus is convinced the teacher he has a crush on doesn’t love him any more. Like most children, Linus takes his minor problems very seriously, and he works through them histrionically. He decides his going to act out his own childish understanding of a grand suicidal gesture in the rain, but he doesn’t take long to realize the downsides…

but he always finds the humor in it. 1968 featured an especially memorable sequence where Linus is convinced the teacher he has a crush on doesn’t love him any more. Like most children, Linus takes his minor problems very seriously, and he works through them histrionically. He decides his going to act out his own childish understanding of a grand suicidal gesture in the rain, but he doesn’t take long to realize the downsides…

In the next day’s episode, Lucy turns up to check up on him and covers him under her umbrella in an uncharacteristic display of sisterly affection. Linus isn’t having it, though, and he offers about as good a summation of the narcissism of misery as you’re ever likely to hear: “Please move your umbrella. You’re throwing me off schedule.”

Rain’s a big deal in Peanuts; “Some things happen in the strip simply because I enjoy drawing them,” Schulz said, “Rain is fun to draw. I pride myself on being able to make nice strokes with the point of the pen, and I also recall how disappointing a rainy day can be to a child.” He was right to be proud: there’s a melancholy beauty to the way those little lines run up and down the panels, especially as the rain comes down harder every panel. This kind of melancholy shows up again in a couple of Snoopy episodes, but his reaction shows again the difference between his outlook and the human characters’:

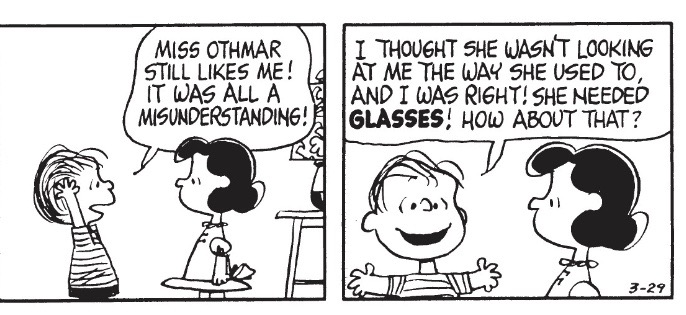

Snoopy and Linus are both wallowing in their misery, but Snoopy knows how to enjoy it; you might say he makes his sadness productive. Again, though, I might be making Peanuts sound much dourer than it actually is. Linus comes in from the rain, of course, and later that week he discovers the reason Miss Othmar “hasn’t been looking at” him “the way she used to” is because she needed new glasses. The story ends with Linus happily “writing a note of appreciation to her ophthalmologist,” and Schulz conveys his overwhelming joy just as elegantly as his sadness in the earlier episodes.

Schulz’s style is so minimalist it’s easy to think it doesn’t take a lot of skill. But the subtle touches in his artwork are something to behold. Just the transition from Lucy hanging up the phone to Linus’ horrified face in this topical episode is funnier that the entire runtime of an awful lot of Hollywood comedies.

While most comic artists treat each panel as a separate unit (something that’s almost enforced now with comic-reading apps that show each panel individually in “guided view”), Schulz was incredibly skilled at creating strips where each scene worked together like a little triptych. Sometimes, he would silently show the progression of a single scene over time with the juxtaposition of each image emphasizing the comedy of subtle changes:

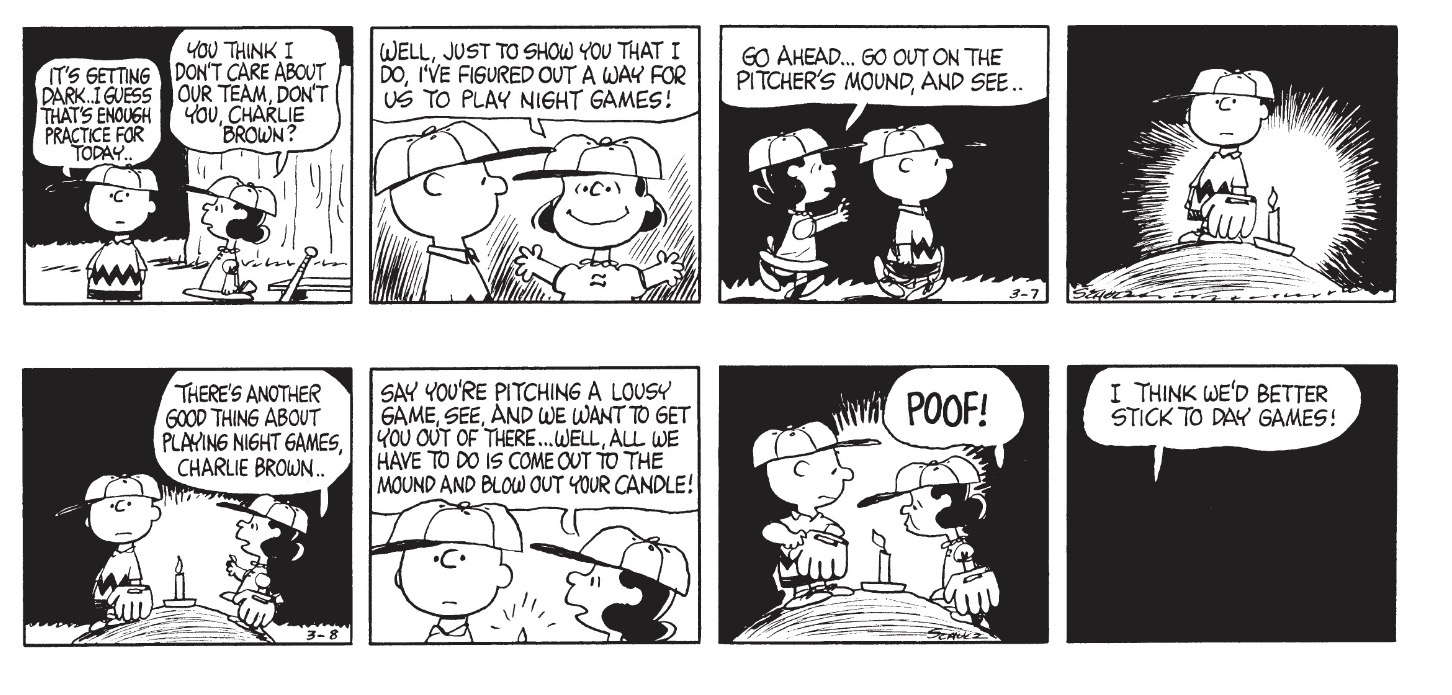

And despite the bluntness of his black-and-white linework, Schulz was still able to create evocative images of light and shadow

And despite the bluntness of his black-and-white linework, Schulz was still able to create evocative images of light and shadow

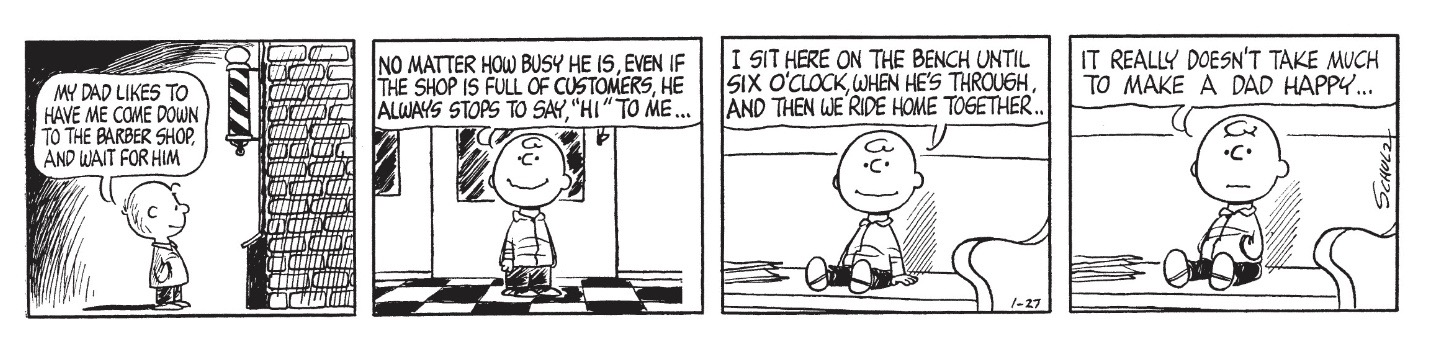

or to create images of tender warmth, like this one that Wes Anderson recreated in Rushmore.

There’s an even better example in these strips, which also show his talent of breaking up the broad comedy of the medium with moments of meditative silence, a talent his collaborator Bill Melendez adapted beautifully to the animated adaptations of the strip. While Schulz himself might dismiss the comparison as too artsy-fartsy, he really was the Tarkovsky of the funny pages.

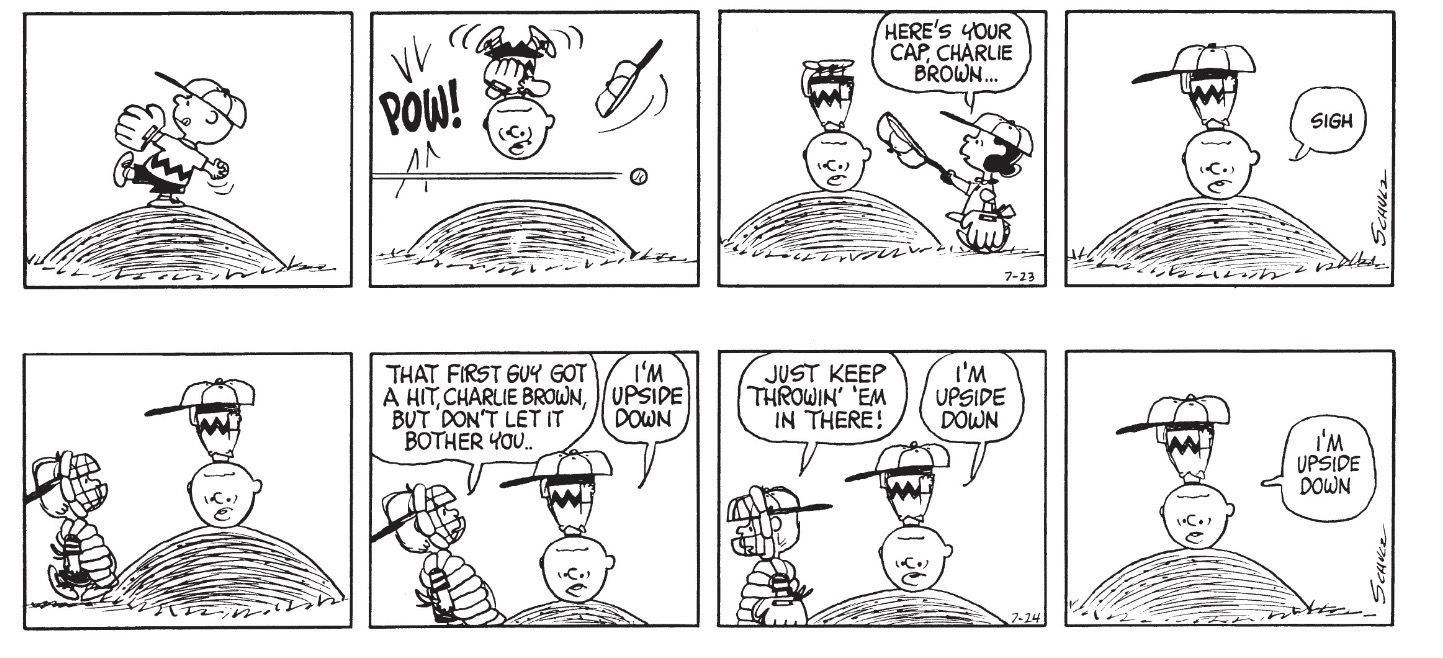

In one of the year’s most representative gags, Charlie Brown gets knocked right onto his head by a flying baseball, to the indifference of his teammates and, apparently, the universe. It’s a pretty over-the-top bit of cartoony slapstick, but what sells it is just how deadpan Schulz plays it:

I don’t know about you, but Charlie Brown’s quiet, repeated stating of the obvious hits my funny bone square in the middle. More than that, it’s a perfect summation of Schulz’s outlook. There’s existentialism in Peanuts, but there’s no howling at an indifferent universe. True to his Minnesotan upbringing, Schulz keeps it down to a polite murmur. Wouldn’t want to be a bother, after all.

I don’t know about you, but Charlie Brown’s quiet, repeated stating of the obvious hits my funny bone square in the middle. More than that, it’s a perfect summation of Schulz’s outlook. There’s existentialism in Peanuts, but there’s no howling at an indifferent universe. True to his Minnesotan upbringing, Schulz keeps it down to a polite murmur. Wouldn’t want to be a bother, after all.

I’ll leave you with a few of the year’s best quotes:

“Goodbys always hurt my throat…I need more hellos…”

“I’m not crazy…I’m just withdrawing from the world.”

“Even stupid questions have answers!”

“Get us some games with some real little kids, Charlie Brown, so we can slaughter them…and then get us some games with some real old ladies and we’ll slaughter them too! Plan our schedule right, Charlie Brown, and we’ll have a great season!”

“The more I worry, the more my stomach hurts…the more my stomach hurts, the more I worry…My stomach hates me!”

“Other people’s stomachs don’t hurt all the time…maybe I have a cheap stomach!”

“I think I’ve made a new theological discovery…if you hold your hands upside down, you get the opposite of what you pray for!”

“Did you see how I struck out that last kid? Pretty good pitching, huh?”

“Yeah, that was that kid who’s been sick all winter…his doctor says he’s going to be alright, but to get out in the sun…he also doesn’t see very well and he’s never played baseball before…”

“Sometimes a catcher can know too much about his opposition…”

“You miss a lot when you sit and watch TV all day long…”

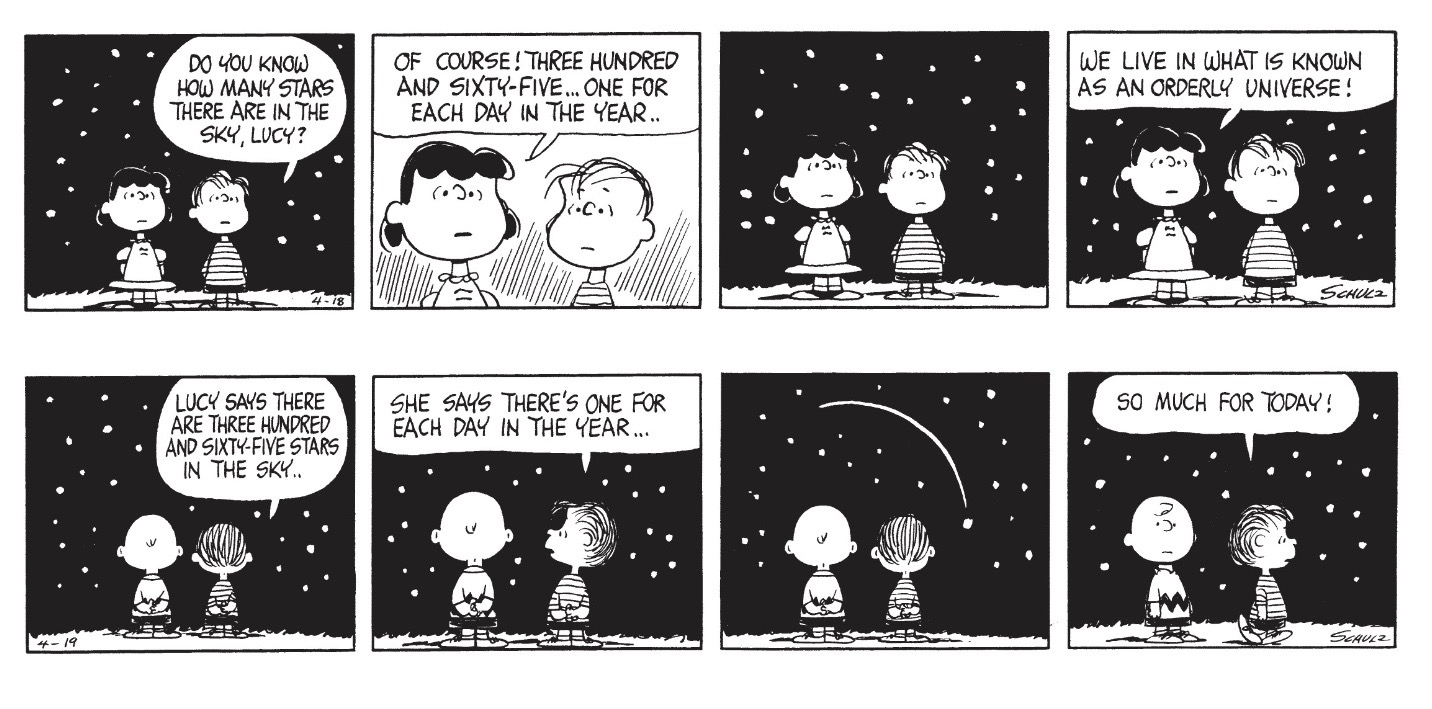

“We live in what is known as an orderly universe.”

“I keep having these tiny self-doubts…Do you think this is wrong?”

“Of course it’s wrong, Charlie Brown…I think you should have great-big self-doubts!”

“For a nothing, Charlie Brown, you’re really something!”

“I find myself always worrying about tomorrow…then when tomorrow becomes today I start worrying about tomorrow again…”

“Happiness lies in our destiny like a cloudless sky before he storms of tomorrow destroy the dreams of yesterday and last week!”

“Your beach ball just left for Hawaii again…”

“English theme…TITLE…’What I did this summer’: This Summer I read comic books and watched TV. Bleah.”

“Miss Othmar isn’t much for biblical admonitions…”

“How disillusioning…I thought my kisses were sweeter than wine.”

“I falsed when I should have trued!”

“If you’re smart, you can pass a true or false test without being smart!”

“Where in the world am I going to get twenty cents? I refuse to sell my Andrew Wyeth!”