Hello, everyone! My name’s Elizabeth Lerner, and although I was one of the first people who signed up for The Solute back when it was just a twinkle in we commentators’ eyes, my life got extraordinarily busy and I was unable for a while to post anything. Now I’m out, and I’m ready to start a series I’ve wanted to do for a long time: Mystery Science Theater Reappraisals.

Yes, I’m open to suggestions for a better name.

MST3K, the famous series in which a dude and two robots trapped in space commented sarcastically on B-movies, introduced me, as it introduced a lot of people, to a lot of movie culture through their sometimes obscure references. But, as I grew older, and as I increasingly came to the position that the idea of talking about films in terms of good or bad in a purely aesthetic sense was much less meaningful outside of a specific context than I previously thought, I started to sour on the parts of the show that rejoiced in disparaging the films that were being mocked. It was one thing to make comments about the characters that exaggerated them and made their essences more explicit, but often I sort of loved that about the films. For example, Agent for HARM, covered in a late season, is one of the best satires of the spy film ever made – far more incisive than Austin Powers ever was – and whether or not that was on purpose, I love it for it.

So, I decided to use this column to go through and not deny where they fall short, but find the little nuggets of interest in them. There’s not always a deeper subtext to find, but there often is, and it can be much more productive to tease these ideas out constructively, pretending or assuming that the creators did it on purpose, and much more enjoyable, than to simply mock and fire contempt at the films like the series did.

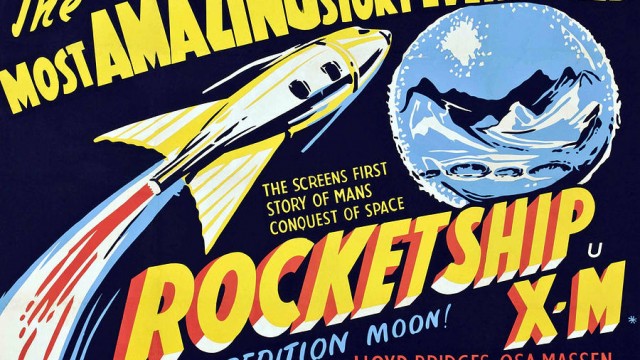

For starters: ROCKETSHIP X-M.

Rocketship X-M is the earliest example that I know of of the mockbuster, the genre later repeated by The Asylum. When Destination Moon, produced by George Pal, was delayed coming out, Karl Neumann decided to capitalize on the public discussion of the production by shooting X-M on an 18 day schedule and putting it into theaters a month before Moon under the title “Rocketship Expedition Moon”. The speed shows: The ship switches from a V-2 in the stock footage of it launching to a much more… well, phallic design for the space shots. This and a lot of other errors were corrected in the 70s by a film exhibitor named Wade Williams, who, because of a childhood fondness for the films, reshot a lot of these scenes. Williams isn’t the only person to have some fondness for the film; it was awarded a Retro Hugo in 2001.

Why do I have affection for it? One character: Dr. Lisa Van Horn. But first, a quick run-through of the plot. A tremendously poorly planned trip to the moon is announced. I say poorly planned, because the astronauts are still sitting around, getting their pulse checked and getting interviews, just minutes before takeoff. Personally, as a perennial early person, the idea of arriving at a movie with the seven minutes to spare the astronauts give their departure makes me break out in nervous pimples, let alone getting on a spaceship, but I admit I’m a more neurotic case than most. Regardless: Spaceship for moon takes off with the five astronauts aboard: the comic relief, who, as he reminds you in every sentence, is from Texas; the designer of the spaceship and Lloyd Bridges’ romantic lead, both of whom we will get into in the analysis; the designer’s assistant, the one woman aboard the ship; and another dude with no distinguishing characteristics whatsoever. There’s an error in the engines, and, after a sequence carefully drained of any tension whatsoever (1) (numbers in parentheses indicate footnotes), when the engines are reignited, the ship flies out of control, causing an oxygen problem that leaves all of the crew members unconscious. And when they awake: They’ve overshot the moon and… they’re at Mars.

Yes. This is insanely unlikely. The movie actually pulls a really goofy move to try to explain it (2) when Karl, the designer, mumbles some mumbo about a higher power, but there’s no defending it. On the other hand: I don’t really give a lick about believability, and any time a work throws away any interest in it, I applaud them. They land their unbelievably phallic spaceship (3) on the surface of Mars, just deciding to… look around for a while. The crew treats finding themselves on Mars as if they got lost on the highway and found a charming little restaurant, not flying through space with extremely limited resources, but that’s neither here nor there. Mars, which looks a lot like California, and in that wonderful way you could only get away with without oceans of nerds complaining before the Internet sprang into existence, requires only an oxygen tank for survival, it turns out, is inhabited – or was; they find ruins of distinctly Modernist architecture and high amounts of radiation, leading to the conclusion that their technological development led them to atomic war. Despite worries of running out of resources, they decide to hang about some more, which leads them to run into Martians, who basically dress like the Flinstones (the shots of Mars are tinted with a red filter that makes race hard to determine). The Martians attack with rocks and axes, injuring or killing off everyone but the two romantic leads. Van Horn finally falls into the arms of Graham, Lloyd Bridges’ character, and as they discover they don’t have the fuel to land, they relay a last message to Earth about the destruction they’ve found on Mars and crash into the Alps. This entire last scene is actually pretty effective and difficult to describe. It cannot be overstated how melodramatic it is, but melodrama gets a bad rap, and it is an effective little scene – or it would be, if Graham wasn’t such an odious character for the rest of the film. In that context, the scene takes on a completely different hue, one that we will dig into now.

INTERMISSION

But first! I should probably give some of my background. I first went to school for literature, and then recently switched to film school, so I have one foot in both traditions. I tend to switch back and forth between my academic side, which focuses more on the ideas and the language of the film, and my filmmaking side, which focuses more on the style and structure of the film. On this site I’ll probably stick more to the former side, which means a more speculative style of writing than you’re probably used to around here. Hope you don’t mind. I’m also a transgender woman, so I tend to be very attuned to films that comment on queerness or femininity. (Obviously, especially films that comment on transgender issues specifically – looking at you, Ace Ventura, you piece of shit.) I already in my academic work try to keep the citational nature of a lot of academic film theory down – the kind that makes a lot of references to names and produces very few actual ideas – so that shouldn’t be an obstacle here.

INTERMISSION OVER

Anyway: I want to examine the character of Van Horn, particularly in relation to the two axes of masculinity (I promise that phrase is as academic as I’ll get) she interacts with: Graham, the love interest, and Eckstrom, the head scientist. Graham’s form of sexism is one that reduces her to the inevitable target of his romantic intent, one whose resistances simply need to be broken down; Eckstrom’s form of sexism is one that reduces her to an inferior intellect, someone not as clever as he is. The thing is, both of these forms of sexism, I think, are not necessarily unintentional. I’m not arguing that this is just the inevitable result of a sexist movie having holes through which we can read more progressive positions; the film seems to be itself commenting on these things. First, let’s take Graham’s seduction. Graham repeatedly tries to get her to think sentimentally, and when it fails, he attributes it to her resisting her status as a woman. He stares out the window and comments on how wonderful the moon is for getting men and women into romantic situations (“Well, on women.” Apparently men don’t need to get into a romantic mood; they are omnidirectional sex desiring machines.) and attributes her failure to want to, basically, start making out like teenagers to her inability to let go and act naturally.

The problem is, we saw her earlier in the movie do exactly that with another character, Corrigan, who is doomed by his lack of defining characteristics. She has no problem thinking poetically, and in fact her poetic thoughts are far more interesting than Graham’s sophomoric high school nonsense. If I were stuck choosing someone to pontificate with, I would pick Van Horn ten times out of ten. Even when Graham pushes her about what he’s imagining – romantic seaside walks – she describes a time she did exactly that with someone. So, basically: Van Horn is completely well adjusted, despite not being interested in Graham’s boner. And of course she’s not interested! At the time this conversation is happening, they are stranded in space. This is exactly when not to sit around, talking about moonlight. He interrupts her doing research on how to get home to talk about making out! It really could not be more inappropriate. I actually like to read Van Horn’s TV-nerd affect when talking to Graham, in light of the fact that she seems to be well-adjusted otherwise, as her purposefully screwing with this irritation that she’s been dealing with for the last however many months of training. She’d fought her way through an ocean of sexism to get into space, so she’s used to it, but that won’t stop her from trying to get it through this beefcake’s head that she does not want to spend any time around moonlight with him. The fact that he opens his romancing with saying that women should stick to having babies and keeping house only makes the whole thing even more ridiculous.

Speaking of general sexism: Let’s look at the other angle, Van Horn and Eckstrom, the ship’s designer. Van Horn is introduced as Eckstrom’s assistant, and he overrules her several times throughout the movie. The first time, she gets extremely frustrated; he arbitrarily decides that, when their separate calculations disagree, that his is right and they’ll just go forward with them. When she gets angry at him for choosing based on no reason except personal bias, she apologizes. We get this exchange: Van Horn: “I’m sorry.” Eckstrom: “For what? For momentarily being a woman?” Actual line from the film. I find it hard to believe that there is not to some degree a knowing wink here of the sexism of the area, particularly because the next time the two disagree, Van Horn is right – the action they’re performing is dangerous, despite the “mathematical theory” being “completely sound,” as Eckstrom says, and launches the entire trip to Mars.

This is already growing to epic status, but I’ll just sketch out how this continues: Their whole relationship can be seen as the conflict between pure science and its real human impact. Reliably, Eckstrom decides that information is worth gathering whatever the cost – after all, he is the one who sent the ship into space in the first place, apparently so poorly designed that it fails twice almost immediately, and he is the one who decides they should stay on Mars, leading to the death of himself and two others. It’s hard, given the atomic war on Mars and the real threat of it on Earth at the time the movie was released, not to read this insistence within the context of the refusal of scientists to consider the human cost of their inventions and their refusal to notice their own human biases, like the sexism he shows to Von Horn.

Again, this is reaching just preposterous lengths, and I’m impressed if anyone read this long. Let me just finish up here. What I am arguing is that this film actually does, despite its sub-B-quality, actually present some, possibly intentional, ideas about sexism and biases in science that are underestimated by those that just mock it. Once you notice her more subtle aspects, Van Horn is actually a pretty great character, the kind of great feminist role that these days would lead to a wave of memes, if not for her complete melting into a quivering pile of objectivized jelly in the last minutes. (But even that we can forgive her; it is not as if one can know if one would hold to their convictions when facing their immediate death and offered a warm person by whom to be comforted.) If anyone has any suggestions for future movies that are better than MST3K gives them credit for, let me know! I might do Agent for HARM next.

(1) It’s difficult to make space as boring as this film does, especially the high-risk act of repairing mistakes, but this movie finds a way.

(2) A move remarkably reminiscent of the last scene of Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol, actually.

(3) No, seriously, it’s a penis. It’s unbelievable how phallic this spaceship is. It’s a dildo with an oven on the end of it.