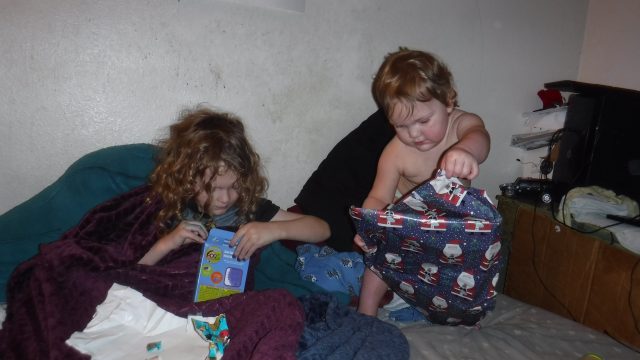

Good Yule, everyone! I hope we all had a chance to watch our movies. I know I did—and I gave my kids Yule presents the night before to make them pose for an article image. (These were just things that wouldn’t fit in their stockings anyway; Irene got a play doctor kit, and Simon got a make-your-own crystal kit. And, yes, she’s wearing a diaper behind that present.) They’re so excited they may still be awake when this article goes live in the morning.

As with last time, I’ll kick things off with my own review. mr_apollo gave me John Huston’s A Walk With Love and Death, as well as helpfully finding a way for me to see it, neveryoumind how. I’ll just go ahead and copy my entire Letterboxd review.

France Has Had Many Revolutions

This is not my era; I’d never heard of this particular peasant uprising until tonight, when I watched the movie. On the other hand, I read a book about a later period of French history that taught me that not learning from your mistakes was a signature characteristic of the French nobility in the sixteenth century, and I have no reason to assume it was a new one at the time. What’s more, 1358 was a year in the midst of great upheaval in Europe; the Black Death was only a few years past. Most of the Crusades were over, but only most. The Hundred Years War had lasted for some twenty years at that point. When wars go on long enough, it becomes possible to believe that they will never end, and that there is no point to continuing the established order because it’s probably the end of the world anyway. At bare minimum, what are the odds that you’ll live yourself? When there are no living souls anywhere, it’s easy to believe that there is no point to anything.

Heron of Fois (Assaf Dayan) was a student in Paris. (Presumably at the University of Paris?) However, the university closed. (Presumably because of the unrest.) However, he is wandering through a desolate wasteland. The countryside is beautiful, he later says, but for the corpses. Both human and animal. He meets a man and begs to buy some wine from him. He encounters soldiers, who then bring in the other man and slit his throat because they believe he is hiding money from them. He ends up in the castle of . . . here’s where I admit that I missed most of the character names and am having a hard time piecing them together from the scanty information available about this film. Anyway. A nobleman. Heron meets the man’s daughter, Claudia (the impossible-to-miss Anjelica Huston), who agrees to be the lady to whom he dedicates his journey to the sea. She gives him a token. Heron is almost to the sea itself when he encounters a band of entertainers, one of whom tells him that the castle has been taken by peasants and everyone in it slaughtered. He walks away just one dune away from his goal to see if his lady survives. She does, and the pair explore the desolation that is Northern France at that time.

This is apparently not a very popular film. Now, partially, it’s just exactly my thing; director John Huston apparently said it did better in France, where they got the context. And it’s true that I’m not as inclined as many other people to try to push ’60s values on everything. I found a review online that suggested Claudia’s defense of her “virtue” was Victorian, but it rang exceedingly true to me of a young girl raised to know that bearing her husband legitimate children was her ultimate destiny. She grew up steeped in the traditions of the troubadours, the ideal of Courtly Love. Of course she believed that hopeless devotion from afar was the ultimate expression of love; she was a fourteenth century French teenage noblewoman. And of course she gives way anyway; see above with the “the world is ending” thing. Better to marry your penniless scholar in a ceremony sanctified only by yourselves than to never be married at all.

I believe that review was the same one that suggested that possibly Anjelica Huston could not act, which does at least prove that you can’t always tell from someone’s first major role. Huston was eighteen, and it was her first real role. Not even “major” role—her only preceding credits on IMDb are a movie called Sinful Davy where she is uncredited and doesn’t even have a character name like “third girl on the subway” or whatever and Casino Royale, where she is uncredited as Agent Mimi’s Hands. (Why Deborah Kerr didn’t do her own hands, I cannot tell you, and I guess Marni Nixon wasn’t available to stand in for them?) If she plays Claudia as someone who doesn’t entirely know who she is, well, is that actually wrong? I think she’s even older than Claudia was supposed to be; the idea of noblewomen all marrying at twelve or whatever is a mistaken one, but she’s still of an age where they should be at least talking about prospects, and none are ever mentioned for her.

I do admit it’s easy to take the film as representing its own era, especially with that dreadful tagline. But that doesn’t mean we should. It doesn’t mean it was intended to. And it certainly doesn’t mean that the ideas it considers weren’t universal. After all, I’m quite sure you could find a lot of people today who embrace the idea that the world is all going to hell and it broadly doesn’t matter what you do. People who say “eat the rich” are probably unaware that there is a period claim that the Jacquerie was doing just that–and forcing the nobleman’s children to watch their mother raped, then force the children and the noblewoman to eat the nobleman’s roasted flesh. These are things which didn’t happen in the movie, aren’t even discussed in the movie, possibly because what we do see and hear is grim enough and that story sounds, hundreds of years removed, not unlike the anti-German propaganda of World War I. Then again, so did the actions of the Germans in World War II.