Movies talk to each other. What did the films of 2023 have to say? This is a look at how two movies from the past year tackle similar subjects in different ways. Be warned: SPOILERS for both The Last Voyage of the Demeter and Godzilla Minus One follow.

As the blockbusters get bigger and bigger, it’s harder for smaller — or relatively smaller — movies to stand out. Corporatized movies reward their various offshoots and suck attention away from flicks that no longer have the ability to hang around on the margins and find an audience. How do you fight the behemoths of Disney and Marvel and Warner Brothers? Well, it helps to have a well-known monster of your own — but you need to know how to use it.

Dracula himself was intended to be part of one of those cinema-flooding conglomerations, the Dark Universe envisioned by Universal in the 2010s. That notoriously flopped, but the monsters have kept coming regardless, unbound by strained connections to a broader world, as Jesse Hassenger documented last year. And why wouldn’t they? The creatures themselves have been deathless for centuries and still offer much to explore. The Last Voyage of the Demeter hits on a potentially untapped area from Bram Stroker’s novel, looking to flesh out what is sketched in one chapter — what exactly happened on the ship that brought the Count to the shores of Albion?

Some C-minus Alien/Thing shit, apparently. The movie opens with the onscreen text of “In 1897, an empty ship crashed into Britain” — it’s not OCEANS ARE NOW BATTLEFIELDS but it’s clearly trying for a historical context– followed immediately by “this is based on the captain’s logs from the novel Dracula,” suggesting right at the start that no one was clear on exactly what side of reality they’re on here. Corey Hawkins, a Cambridge-educated doctor who is in Bulgaria instead of practicing in Britain because of Racism, winds up aboard the Demeter as it sets off toward London with a bunch of crates delivered by some sketchy villagers. Once at sea, the crew discovers an exsanguinated but still living young woman in the crates and a bunch of mysterious livestock deaths in their food supply. The most racist crew member sensibly suggests there is a damn monster aboard, he is ignored. Even though, as everyone watching the movie knows, there is a fucking Dracula amidships. Oceans are now slaughterhouses.

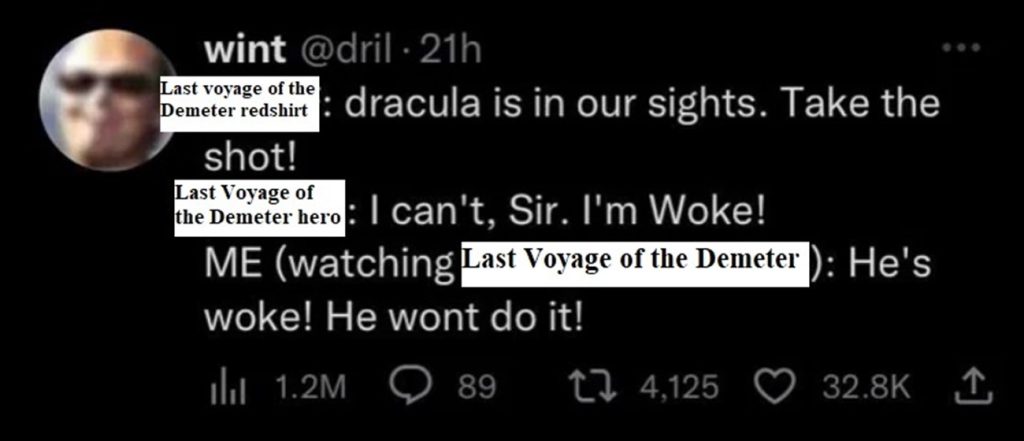

Director André Øvredal gets off a few decent sequences of horror, the best involving the captain’s damn wiener kid stuck in a cabin with the Count, but way too much of this movie is by- the- numbers spooky noises/investigations/jumpscares. Peter Weir made his ship a world in Master and Commander: The Far Side Of The World, here the vessel is an obstacle course. Dracula himself is a fanged and feral Nosferatu, which is perhaps more vicious than the urbane and seductive vampyr we know, but why trade that uniquely threatening but known menace for a bog-standard boogeyman, generic and thus even more contemptuously familiar? This lack of shock, of recognition that surprises and disturbs, is what sinks the larger story. The ending of Drac taking England by storm in a Transylvanian Invasion is known, there needs to be something else driving our interest in these characters, and what writers Bragi Schut Jr. and Zak Olkewicz land on is Hawkins and Aisling Franciosi’s stowaway — a bBlack guy and a young woman — being symbols of oppression, not able to be all they can be because of society. Hawkins describes being discriminated against in the supposedly civilized Cambridge and how he was turned away from plying his trade from his home country and his college reminiscing is coming as a god damn Dracula is running around his fucking boat. Hawkins’ whole insistence on a rational explanation for various Drac-related killings on board is not an interesting character flaw to explore but the creaky engine that drives the plot, the guy who keeps making people not take actual action because he’s too “enlightened.” The Last Voyage Of The Demeter was released in the dog days of summer, but way back in January someone already had an idea of where it was headed:

The hero of Godzilla Minus One is not too woke, but he is too afraid. In the last days of World War II, kamikaze pilot Ryunosuke Kamiki fails in his suicide mission and then is too petrified to shoot a giant but not titanic lizard stomping around the island air base he’s hiding out at. Said lizard, who the island natives know as “Godzilla,” kills nearly everyone at the base before going back to the sea, where it eventually swims over to Bikini Atoll as the U.S. is testing an atomic bomb. Meanwhile, Ryunosuke has gone back to Tokyo and wound up in a thrown-together family with a plucky young woman who has rescued an infant from the wreckage of U.S. bombs. The bomb’s radiation turns Godzilla from terrible lizard into furious deity, increasing his size and scarring his body and maddening his mind; but Ryunosuke may actually be in worse shape. He’s sweeping the ocean for mines with a can-do crew, going home to his not-quite-wife and not-quite-daughter, but he is consumed not just by survivor’s guilt but by the idea he did not act with honor. While he is still among the living, he does not want to be alive.

As the title Minus One suggests, this is framed as a prequel to the original Godzilla (1954), and the ultimate outcome can’t be in doubt. But writer/director Takashi Yamazaki has thought things through where the Demeter folks have not. That movie pits characters with uninteresting motivations against a monster with no menace. Godzilla Minus One‘s story of redemption is melodramatic but unlike the Dracula movie, it has stakes. “Will Ryunosuke learn to embrace life?” is a question that is up for grabs with a meaningful answer, “Will Hawkins realize that he’s on a boat with a fucking Dracula?” is not. And while both movies have foreordained endings, Takashi understands that the journey is more important than the destination, and how what we see along the way will last long beyond the conclusion. There have been several U.S.-made Godzilla movies over the past decade and while Gareth Edwards’ 2014 flick has an understanding of how to treat the character, the subsequent flicks are swamped in boring lore and putrid, contemptible banter. Watching Godzilla is not as important as making a snarky remark about him, according to Godzilla: King Of The Monsters, but another movie about a monster points to the proper path: In Manhunter, serial killer Francis Dolarhyde — the Red Dragon — lectures a victim about what a being like him is due. “Before me, you rightly tremble. But, fear is not what you owe me,” the Dragon declaims. “YOU OWE ME AWE.”

And awe is what Takashi delivers. The opening attack on the island does a damn good job of placing the viewer in Ryunosuke’s shoes — shoot THAT? And survive? No fucking way — but it’s when Godzilla is at full capacity that the movie really shines. He attacks Ryunosuke’s crew of minesweepers, churning through the ocean like an enormous crocodile, and the boat’s skin-of-their-teeth escape just sets up Godzilla destroying a full-on battleship like it was nothing. This is shown in broad daylight, as is the centerpiece where Godzilla comes ashore and stomps Tokyo (specifically the Ginza district). Godzilla swims easily but on land his bulk has him moving, as one critic put it, like a guy who’s dropped a load in his pants. In an interview with Indiewire, Takashi describes the waddling effect but makes a different comparison: “In terms of the bottom half of Godzilla, we made it feel very heavy and dense in a way that made the viewer feel like this mountain and triangular silhouette was walking and moving through a space So imagine the [Imperial] Star Destroyer from Star Wars.’”

That opening crawl of the Star Destroyer is about peeling the viewer’s eyelids back, making them acknowledge the scale at play here. But the Star Destroyer is still just a ship in the expanse of space, Godzilla is something beyond human comprehension that is nonetheless moving through our human world — Takashi does a phenomenal job of cutting between wide shots of Godzilla in the city and ground-level views of what a person would see, the barest bit of a leg blocking out the sun or a head moving past a roof right before the entire building is toppled. Godzilla is not the agile and secretive demon of Demeter, the point is we can see but not comprehend. I watched both of these movies in the theater and Godzilla’s nuclear breath exploding part of the city had my mouth hanging open. Dracula had me rolling my eyes.

I’ve forgotten what the plan to stop Dracula was, it was pretty stupid and too late and led to a noble self-sacrifice from Franciosi that played like a simpleton’s rewrite of her character’s ending in Jennifer Kent’s The Nightingale, a movie with more horror in any five of its minutes than Demeter’s two hours. The plan to stop Godzilla in Minus One is almost cheerfully ludicrous — rapidly sinking him to the bottom of the ocean where the pressure will hopefully crush him, and then just as rapidly bringing him back up, giving him a fatal case of the bends — but it’s memorable and based in applying physics to a 400-foot-tall monster, something you don’t see every day. And instead of Demeter‘s tedious paranoia and confusion prolonging the issue of dealing with fucking Dracula already, the sink/raise Godzilla plan is based in hundreds of people working together to pull off its moving parts, a massive scheme to stop a massive monster. “Will this action work?” will almost always top “Will people take action?” as a question to see play out on screen.

And the second question can work within that first question. Ryunosuke’s part in the plan is to fly a plane full of explosives into Godzilla’s big ugly face, what remains to be seen is whether he will stay on that plane and complete his mission from the start of the movie or eject, taking on a new mission of living with and for the people who support him. This is very corny and broad, but the scale Takashi has created for his monster has room for this outsized drama as well. It may not have room for the coda — Ryunosuke bails but lands a bullseye on Godzilla, blowing up his dome and saving the day, and he returns to the mainland to find a character thought dead is miraculously still alive — but the happy ending works for me. Demeter‘s soppy tribute to human resilience or whatever feels like a sop to current standards of weak humanist tea; Minus One believes in its humans as much as it does its monster.

And it’s not like these movies truly end. At one point in Minus One we see a wounded Godzilla regenerate its flesh, the final image is the creature’s blasted skull reforming at the bottom of the deep blue sea. Hawkins survives his ship’s grounding and is wandering around London when he hears Dracula mocking him; he swears vengeance. The monsters will return — in theory. Demeter didn’t even make half its budget back, boding ill for any further fearless vampire hunting from Hawkins, but Minus One’s boffo BO surely indicates a sequel. Godzilla Minus One was a surprise hit, making more than $100 million worldwide and topping the box office in the U.S. after being made for a reported $15 million. That figure is inconclusive, exchange rates and low pay for effects workers could also be a factor, but it is almost certain that the actual number is lower than Demeter‘s $45 million budget and it is inarguable that the movie with a third of the budget looks a hundred times better. And Minus One already looks better than the next U.S. Godzilla movie coming out in a few months, an eight-figure effects fest where Godzilla and King Kong team up and run around with the goony goofery of John C. Reilly and Will Ferrell in a back-when-he-was-still-funny Adam McKay movie. But focusing on money is too much in line with what the trade publications and bean counters care about, figuring out who’s getting paid what and determining cost without understanding value. Without understanding that there are other things to be owed, like awe. Who are the real monsters around here, anyway?