Movies talk to each other. What did the films of 2023 have to say? This is a look at how three movies from the past year tackle similar subjects in different ways. Be warned, SPOILERS for Barbie and Asteroid City follow.

A movie has a beginning and an ending, and someone to decide when those things occur. A movie (often) has a story, something that can be understood when viewed in full, and someone who decided what that story will be. Movies are compared to dreams, but dreams begin in uncertain circumstances and end abruptly, often without a sensible storyline and usually without a clear conclusion. In that sense, they’re very much like life. It’s hard enough to understand a dream, making sense of existence in the “real” world is even more fraught. Are our lives dreams, made up as they go along? Who’s in charge of this place, anyway?

Trying to leave the party

Barbie lives in a Dream House but it’s unclear if she dreams. She does wake up every morning and go out into the world of Barbieland run by her fellow Barbies and created by a combination of children using dolls to dream and a corporation using products to get extremely rich. Her life is great, an endless party — until she starts thinking about dying because a woman named Gloria whose daughter no longer plays with her Barbie is thinking those same thoughts, feeling the frustrations of existence and specifically existence as a woman in a world designed to stymie women. The Real World, where Barbie and her faithful companion Ken journey to and encounter both Gloria and the Mattel corporation (where Gloria works), and where Barbie only gets more confused while Ken discovers a patriarchy that tells him he’s always right.

One of the strange things about Barbie’s structure is how Ken is initially the most dramatic character — while Barbie wants for nothing in Barbieland, by design Ken wants to be with Barbie and is frustrated by her polite but definitive rejection. Ryan Gosling’s performance is very funny throughout the film but he sells this longing too, along with the almost fearful joy at finding a place that encourages him to be and take whatever he wants. He returns to Barbieworld and indoctrinates his fellow Kens into male dominance and the other Barbies into domestic subservience, making their world his. The party belongs to him, although it’s still at Barbie’s house. And Barbie is stuck in the real world, but also in her own confusion at no longer wanting what she once wanted. Margot Robie also gets lots of funny bits but her character is overwhelmed by something different than longing. She can’t see a way forward but knows she can’t go back to that endless party. No longer knowing what to want and only being sure the world is arranged to not let her get it, Barbie is learning about loss.

Longing and loss suffuse the characters of Asteroid City, not that they’ll be open about that. In the 1950s, photographer Augie Steenbeck rolls into the title town with his children, who he hasn’t informed of their mother’s death — although teenage son Woodrow probably knew the whole time. Woodrow is the reason the clan is in the Southwest, he’s showcasing his science project alongside four other prodigies for the benefit of the U.S. government, and his quiet grief is countered by a desire to explore the stars and to reach out to his fellow nerds. He connects with a young woman named Grace as Grace’s mother Midge, a Hollywood actress of some note, finds a complementary link with Augie — single parents who keep moving without certainty, trajectory without the precision of an orbit. And who could predict how the teens’ Junior Stargazer award ceremony would be interrupted by a visitor from the stars themselves, as an alien’s brief landing leads to the entire town’s quarantine?

Well, Conrad Earp could. Considering he’s writing all of this. “Asteroid City” is a play that Earp and director Schubert Green are putting on, also in the 1950s, wrangling actors’ egos and their own personal problems, and the potential confluence of these things through Method acting, actors pulling from their own emotions and experiences to inform performance. The viewer of Asteroid City sees these preparations for “Asteroid City,” because the creation of the play itself is being dramatized for a television program — the program’s host periodically steps in to directly address the viewer about this. But sometimes he winds up in “Asteroid City,” and the actors there, in particular Augie portrayer Jones Hall, duck out from the play when they’re not on stage to badger the writer and director for advice. Jones is the star of the show but like Augie, he doesn’t know his motivation. Like Barbie, they’ve lost the plot and lost themselves.

What if nothing was pretty?

As an actor, Greta Gerwig came up in the mumblecore scene, where low-level artists made low-budget movies about low-key lives, the characters’ similarity to their creators’ being entirely intentional. As a director, Gerwig has moved toward increasingly complex storytelling, going from the coming-of-age Lady Bird to the scrambled timeline of Little Women to the moving between worlds of Barbie, finding visual signifiers to guide viewers along the way. She has a lot of fun making Barbieworld’s vivid colors and artificial accessories contrast with the “real world,” but also uses the openness of Barbieworld in interesting ways. There are no walls to hide behind in Barbieworld because everyone there is an object to be seen — this is not creepy but liberating, because as objects with a clear purpose (President Barbie, Doctor Barbie, etc.) the perception is recognition and fulfillment and celebration. There is no questioning of existence, if you are Doctor Barbie you Doctor, so walls become frames to showcase action. Ken and his Kronies re-objectify the Barbies and their World but tellingly keep its architecture. And while the Mattel board members who run things in the real world are happy to maintain their patriarchy, they also are not about to make too many structural changes, telling an underling who’s asking metaphysical questions about travel between Real and Barbie worlds to just shut up, already.

Wes Anderson wouldn’t even recognize that question of separate worlds. He has always emphasized the visibility of his movies’ construction, emphasizing textures and objects in the same way Gerwig lovingly replicates the plastic aesthetic of Mattel, but the nested structures of his recent movies have really called attention to his authorship (and that of his co-writers — frequently Roman Coppola and Jason Schwartzman but Barbie cowriter Noah Baumbach is an old collaborator too). The Grand Budapest Hotel is a reflection of an author about his meeting with a man who told him the story that takes up most of the movie; The French Dispatch is organized as a series of magazine articles where the authors all wind up participating in the stories they’re describing. “Asteroid City” is a play, but in the film it is shot in widescreen and filmed in bright hues to rival those of Barbie; the documentary re-enactment is shot in black and white on obvious sets. “Asteroid City” initially presents itself as a work to be taken at face value while the re-enactment makes no pretense that it is a production, complete with the TV show’s narrator setting scenes for the audience.

Gerwig and Anderson are creating purposefully complicated worlds here, ones that show riches in every corner when they’re not turning in on themselves. The details are not extraneous or distracting, they are all part of the creation. But these creations don’t encompass creation itself. Along with eliding travel between worlds, Gerwig is cagey about the bond between Barbies and their — owners? Users? Mattel creates Barbies but they are brought to life by the people who play with them, and thus their lives are not really their own. This is fine for most inhabitants of Barbieworld but not Barbie herself, and after she and her doll and human allies retake Barbieworld she realizes she no longer wants to live there. And in a third blurring of lines between worlds, Barbie creator Ruth Handler (not really her of course, it’s Rhea Pearlman) returns from wherever the dead go and tells Barbie she can do whatever she wants. “You don’t need my permission,” Ruth says, scoffing at the notion that as “The Creator,” she controls her creation. “I can’t control you any more than I could control my own daughter!” The metaphysics are again hazy but what comes through clearly is how Ruth is not bestowing anything but giving Barbie the space to reach her own conclusion about how to live her life. In Asteroid City and “Asteroid City,” Conrad Earp puts words on the page and Jones Hall reads them and Augie Steenbeck comes to life. But how? (Well, through the acting of Schwartzman and Ed Norton) And why? As Asteroid City hits its climax of a second alien appearance and chaos breaking out among the quarantined, Hall sneaks away and questions Green (Adrien Brody, another Anderson regular), trying to figure out his motivation and his place in the performance. “I still don’t understand the play,” Hall says. “It doesn’t matter. Just keep telling the story,” Green responds. It’s comforting guidance. Does directing actors portraying people who’ve lost their partners help Schubert Green, whose wife has just walked out on him? Does cataloging the stars change what they are and their distance from us, the paths they’re on and their eventual ends?

What if we never had to sleep?

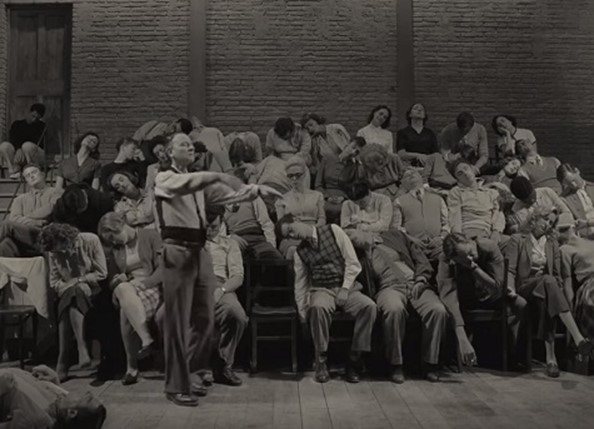

“Sleep is not death,” an acting teacher tells Earp and Green and Hall and the other performers who will create “Asteroid City.” “The body keeps busy … important things happen. Is there something to play? I think so.” He’s speaking as the group tries to fall asleep as an acting exercise, in order to figure out how Earp can create a sleep scene for “Asteroid City.” This scene never appears in the play. But after more intertwining of the various narratives, Asteroid City returns to this scene as the Narrator tells us that six months into “Asteroid City”‘s run, Conrad Earp crashed his car and died, and the sleep connection is as explicit as it can be. And then, in a film full of layered reality, the characters break the final barrier and reach out to us in the audience. Looking at the camera, they chant over and over: “You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep!”

“I created you so you wouldn’t have an ending,” Ruth tells Barbie. “You understand that humans only have one ending.” And before Barbie makes her final choice, Ruth shows her what she stands to gain and lose, glimpses of “happiness, sadness, big moments, little moments, childhood, adulthood, old age, how it all rushes by in one moment,” as Gerwig and Baumbach’s script describes it. It’s not a look into her specific future but it’s her Creator — the original Author — letting her know how real life works. It’s in the details, the accessories, how a person is a subject creating subjective meaning through objects. My favorite moment in Asteroid City comes when one of Woodrow’s fellow teens has figured out a way to break quarantine, hack a payphone and contact the media — specifically, his partners at the high school newspaper. “I wouldn’t disturb you if it weren’t of the utmost importance to the Weekly Bobcat,” he intones with utmost seriousness to the mother of his fellow journalist, and Anderson knows there is a joke and a truth in something being important to the Weekly Bobcat, to these dweebs putting out a newspaper. Something that is famously short-lived, but aren’t we all? Compared to a space rock that’s sat on Earth for millions of years, or an idea that, as Ruth Handler says, can “live forever.”

This creation of importance runs through all of Anderson’s work, his obsessions are mirrored by those of his characters. They’re searching for something to devote themselves to, just as Anderson is trying to find the right song or piece of clothing, and arrange everything perfectly in the frame. He knows this is ultimately futile but the attempt has value, for the little time we have. Death also runs through all of Anderson’s work; no one dies during “Asteroid City” but the play revolves around the death of Augie’s wife and Woodrow’s mother before the action begins. And in Asteroid City, the author is dead at the end. The players are adrift. All they can do is keep telling the story without him, and to fake it until they make it. At his moment of crisis, Jones Hall leave the theater and runs into the woman who was set to play Augie Hall’s spouse, before she was cut from the play. “You’re the wife who played my actress,” says the actor playing a character who is of course an actor — Schwartzman, who broke out with Anderson nearly 30 years ago and has acted and written with him since — playing a character; he is speaking to an actor playing a now-nonexistent character who is of course an actor — Margot Robbie, the star of Barbie — playing a character. I don’t think any of this adds up or locks in, and it’s not supposed to. Art is not a rehearsal for life, it is a way of living. To create and see outside of yourself and back into yourself, through the screen or the stars or the Daily Bobcat. At the end of the movie, when quarantine is lifted and everyone can get on with their lives, Woodrow tells his dad he’s an atheist — he’s rejecting the idea of an Author, but he’s not giving up on his own explorations, piecing together what he can. Earlier, he and his friends played a memory game where they recited an increasingly obscure list of scientists and people who made significant discoveries; the kids agree they could probably do it indefinitely. It’s an utterly charming display of pure nerdery and another obsession, but it looks backward to others’ accomplishments. Woodrow is ready to move on and to recognize what he’s lost. “Writing is the most improvisational part of the whole process,” Anderson told an interviewer about creating Asteroid City. “It relies on having nothing.”

Barbie has nothing — just ask her gynecologist. Because Barbie makes the choice to become a real woman, a mortal being instead of a deathless doll. She meets her author and then makes the choice that none of us has ever gotten to make, she decides to be born. If Barbie is given more certainty than the characters of Asteroid City, she also loses more with the rejection of that certainty. She wakes into a mundane world with the knowledge that she’ll have to go to sleep one day and never wake up. But she was just someone else’s dream before. As Greta Taylor has argued, Barbie can be read as Gerwig’s own version of Barbie’s choice to “be part of the people that make meaning, not the thing that’s made.” She’s taking the Andersonian point of view while pointedly swerving away from something similar to his aesthetic. But she and Barbie are not fully striking out on their own. Making meaning is hard, it helps to have friends — Barbie has her partners in matriarchy and one of the ongoing pleasures of Anderson’s films is seeing how his troupe of recurring players over nearly 40 years continues to grow. Way down at the end of the credits for Asteroid City is a list of people who worked at the hotels in Spain where the movie was made; I’m an inveterate credits watcher and I’ve never seen that level of service officially recognized for helping to make a movie. It could be Anderson’s obsession at work again, trying to account for everything — the author writing it all down and controlling the narrative. It could also be a purposeful expansion of the people who make meaning, set down in the thing that is made.

Barbie the doll, Barbie the character, Barbie the movie, “Asteroid City” the play, “Asteroid City” the making-of, Asteroid City the movie. It all blurs together until the credits roll and we step back and into our own lives again, the details of the dreams on the screen still lingering in our minds. You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep. We play at being alive until we die and we won’t find out until then if there is a creator to meet afterward. For now it’s just us, and if it’s hard to reconcile that no one person is truly the author of their life it is almost impossible, for me at least, to truly grasp the concept of an ending. But I have Barbie’s affirmation and Asteroid City’s acceptance, their joy in the minutiae and their acknowledgement of the ache and understanding in the Fastbacks’ semi-ironic lament: “Think how much easier life would be if we never looked around.” These colorful, funny and energetic dreams are also deeply melancholy rehearsals for that final sleep, but their authors offer so much to see along the way.