Movies talk to each other. What did the films of 2022 have to say? This is a look at how two movies from the past year tackle similar subjects in different ways. Be warned, SPOILERS for Nope and The Fabelmans follow.

“This business will rip you apart,” an old John Ford cautions a young Steven Spielberg, I mean Sammy Fabelman, at the end of The Fabelmans. Sammy is too awestruck for the warning — an echo of a similar one from his entertainer uncle — to land. He’s ready to make some movies, like one about a shark that rips people apart and rewrites the movie landscape creating a world of four-quadrant blockbusters. The business is changed, it always changes but coheres around the latest development and moves on. The artists within that business — that’s another story.

Jordan Peele’s Nope is about making art in a restrictive system. And about racist erasure of artists. And about the uncomfortable relationship between artist and audience. And about an artist’s inappropriate relationship with a monkey (The Fabelmans is also about this). And, occasionally, about ripping people apart. Said ripping happens when a giant flying alien jellyfish thingy sucks up and pukes out a bunch of people at a cheesy Old West theme park run by Jupe, the former child star of a cheesy 90s sitcom; but even more memorably during a flashback to that sitcom, when Jupe’s chimpanzee co-star mauled the rest of the supporting cast after being startled and was subsequently shot to death. Peele uses suggestion and violence on the edge of the frame for the sitcom slaughter but borrows from Spielberg for the nightmarishly effective alien setpiece, particularly the similar chute of digestive death from the tripods in War of the Worlds.

And as many people noted when the movie came out, there is a fair amount of Jaws in the back half of the movie, when siblings OJ (taciturn, tough) and Em (gregarious, obnoxious) team up with Antlers (grizzled, maniacal) to hunt a monster. Things do not go well for the psuedo-Ahab, and one of the remaining members is left for dead but miraculously re-appears unharmed after a final act of desperate, righteous “shooting” from the other. If Nope didn’t put up Jaws-like numbers at the box office it was still a hit, making nearly three times its $70 million budget, and getting rapturous reviews digging into the movie’s themes.

There sure are a lot of themes to dig into. Daniel Kaluuya’s OJ and Keke Palmer’s Em squabble as siblings with different takes on how to get ahead in Hollywood, with Em being a networking whirlwind and OJ a person holding onto his family’s horse-taming and -riding history. But both play up the Black roots of equine showmanship and moviemaking in general and both decide to get images of that giant flying alien, to make a movie about a carnage-causing creature in order to make some money and save the old Haywood family ranch. Steven Yuen’s Jupe is obsessed with his own encounter with a wild animal and also pursues the menacing beast, but doesn’t take into account that animals don’t like direct eye contact — to be viewed. The spectacle consumes the spectator, technology proves unhelpful, pursuit of artistic excellence leads to gory death. This business will rip you apart.

Peele has facility with classic cinematic convention (an early fakeout alien invasion is shot with the perfect creepy distance from the threat) and a willingness to push boundaries, his monster really does look like something new. But his ideas feel considered first as themes and half-considered at that, instead of arising from the story he’s telling. Some critics compared Nope to the great Tremors, and being put next to the fleet latter does the lugubrious former no favors. Peele’s emphasis on allusion over action winds up affecting the filmmaking as well — the extended showdown is clearly understandable from moment to moment but hard to parse as connected events. The movie contains tons of nods and references (MAD Magazine! Chris Kattan!) and clever bits, and one of the latter serves as a metaphor for the film — an air dancer gyrating and gesturing all over the place yet remaining rooted to the same spot, the wind slowly leaking out of it.

Watching is destructive in Nope, which many reviewers noted was an inversion of the Spielbergian trope of watching characters themselves watching something in awe. Watching will get you killed! In The Fabelmans, young Sammy/Stephen is horrified by his first watch of a movie in the theater, beset by nightmares after seeing a train crash. He soon recreates the scene for his own camera and conquers his fears, sewing up the rip in his mind. And then he makes a new movie, where one sister plays dentist and rips out another sister’s bloody tooth (ketchup, ma! it’s OK!) for the watching camera. After all, this movie is called The Fabelmans, not The Adventures of Young Sammy — destruction and pain for the viewing audience is a family affair.

Staging pain for entertainment is what Sammy does throughout the movie. Unlike OJ and Em, he never really has to worry about the means to make his films — his father can afford to get him a camera and editing setup and his mother provides endless encouragement; late in the movie his girlfriend’s wealthy parents provide a big equipment upgrade with no problems. Sammy starts at the bottom of the industry Nope’s leads are still on the margins of, but gets to meet his hero and is clearly set on a path to greatness, no need to risk his life grabbing a glimpse of a UFO. But that doesn’t mean he doesn’t have his own issues ripping him apart.

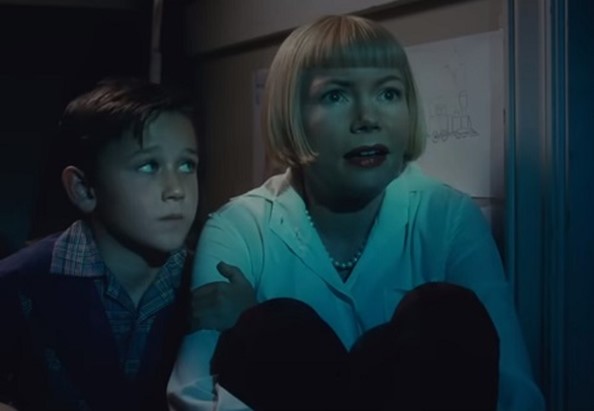

While The Fabelmans seems to amble (heh) along, it shows a progression of pain. Sammy’s early movies treat injury as a technical issue, how to get that toothy blood or show a more realistic gunshot, but soon they reflect and cause deeper wounds. Around the time Sammy’s circus entertainer uncle warns him that art and family are incompatible, Sammy sees in his home movie footage evidence that his mom is in some kind of relationship with his dad’s best friend. He edits this out of the film he creates for family consumption, but shows mom Mitzi — a frustrated artist herself and Sammy’s biggest fan — a supercut of implications of infidelity, leaving her a crumbling wreck on his closet floor. This only comes after a distraught Sammy creates his latest fiction about a military leader — an authority, a parental figure — consumed by anguish and regret by the agony his decisions cause those under him. Sammy processes his pain in one movie, although he doesn’t seem to realize that’s what he’s doing, and shares it in another, even though he does know what kind of rift it will cause.

The last movie we see Sammy make is another home movie of sorts, the official record of his school’s “Ditch Day” for seniors at the beach. This class of bright-eyed 1960s youths includes a couple of antisemitic bullies who have caused Sammy quite a bit of pain and he makes one look like a pathetic loser, much to his classmates’ amusement, but makes the other look like a jock king at his zenith of physical beauty and prowess. The gaze of Sammy’s camera shows a golden god and the bully knows the image is a lie. He feels ripped apart, and it really is unclear how much Sammy meant this to happen — how much he knew his art would affect his subject, versus how much he cared about getting the most power out of his images, regardless of effect for good or ill. The secondmay be the more disturbing conclusion.

Because it suggests a person ripped apart from others and himself, an image literalized in a remarkable scene set before the Ditch Day screening. The Fabelmans as a unit have been falling apart all movie and mom and dad finally, tearfully announce their divorce and Sammy’s sisters break down as well. Sammy is sad, but he’s also seeing the possibilities here, and we get a visual of his reflection processing the bloodless and commonplace yet devastating destruction of a family by what else — filming it. Preserving the rip on film so he can re-edit and present the pain. Which is of course what Stephen Spielberg is doing here, with the help of Michele Williams as mom Mitzi and especially Paul Dano as dad Burt. Spielberg shows their love and frustrations and mistakes, looking back on how a kid could never really understand his parents as humans capable of failure. The distance between Sammy not considering how much Burt has lost and how Spielberg is able to show this from his own perspective now is not a rip but a chasm, and how the movie is the only bridge Spielberg has now is its own deep pain.

OJ and Em lose their father at the start of Nope — he’s a victim of the alien’s inability to digest non-organic material, perhaps another thematic element of rejecting “fake” life and embracing “real” life? — and while they each had their own complicated relationships with the man, they are adrift without his stabilizing influence, his link to the past they’re trying to live off of and honor. But they ultimately work toward the same goal after butting heads earlier and OJ seemingly sacrifices himself for his sister, before making a re-appearance that, as previously noted, is so inexplicable it only makes sense as a direct nod to Richard Dreyfus’ return in Jaws. But while Dreyfus surviving is implausible, it feels completely right in the context of the movie itself, and Peele seems to be going for a similar resolution based on what a movie can offer more than what is logical. He closes with OJ coming into view astride a horse, an archetypal visual and indeed an echo of the image of the first man on film, an unknown (not bothered to be known) Black jockey in Eadweard Muybridge’s Animal Locomotion, which is referenced by the Haywoods as their own origin story. The image-conscious Em has captured the image that will make her famous and OJ, the man behind the scenes, is now the star. It’s a Hollywood ending.

Young Sammy’s meeting with John Ford (an irascible David Lynch) at the end of The Fabelmans is based on Spielberg’s own well-documented brief encounter with his idol. And it’s very funny, with Spielberg wryly depicting Sammy’s awe and Ford’s useful but blunt and tossed-off advice about finding a horizon somewhere other than the center of the frame from the perspective of a man able to laugh at what his younger self couldn’t quite see. And this mood seemingly extends to the last scene, where a Sammy who is ready to embrace life in Hollywood is nearly dancing as he walks through the studio backlot toward a horizon in the middle of the screen — until an unseen hand cheekily jiggers the camera so it follows Ford’s guideline.

This got a big laugh in my theater, and I’m sure that was the intent. But it’s also literally Stephen Spielberg reframing his story in a way that ends on a high note that leaves the viewer happy. Which, coming at the end of a movie that has shown the rawness and messiness and destructiveness as well as pleasure of creating and consuming art, can’t be an accident. And come to think of it, there’s no one else wandering around the CBS studios Sammy is passing — after the story of The Fabelmans and the pain they have lived, he’s alone with his movies. He’s happy — like David is happy in AI: Artificial Intelligence and like Tom Cruise is happy in Minority Report, two Spielberg movies that are very ambivalent about whether that happiness is real. Peele is trying to interrogate the biases and bloat of the industry that made Spielberg and that Spielberg helped make a global juggernaut, while also producing an entertainment of Spielbergian craft and depth. He wants to rip up the world of movies and put it back together in a way that pleases him, Nope feels like something only Peele could make but also like something that is not actually good. The Fabelmans feels like something only Spielberg could make and, more compellingly, that Spielberg could only tell in this cognitively dissonant but crowd-pleasing way. Spielberg rips himself and his family apart and puts the pieces back together in a way that pleases the audience, like a magician sawing himself in half while telling the spectators not to mind the blood. Now that’s entertainment.