Movies talk to each other. What did the films of 2021 have to say? This is a look at how two movies from the past year tackle similar subjects in different ways. Be warned, SPOILERS for Red Notice and Salesmen follow.

What do you need to make a good movie, one that lots of people will want to watch? Well, big stars probably can’t hurt. And people like escapism, getting away from their lives for a bit, especially in a shitty year where actual escape was impossible and had dangerous consequences a fair amount of the time. Some popular actors taking outsized actions in exotic locations, that’s not a guarantee of success but it sounds pretty good. Figuring out what makes a good movie is more art than science anyway, as opposed to figuring out how many people watched a movie. That’s just math, right?

The Netflix release Red Notice made history last year as the biggest movie released by Netflix, according to Netflix. By the end of November it accounted for 330 million “viewing hours,” nearly 50 million more such hours than the previous top Netflix Original Bird Box, a movie from 2018 that everyone remembers. Using numbers from a few weeks later, Looper did the math and calculated 185 million views of the two-hour movie starring Ryan Reynolds, Dwayne Johnson and Gal Gadot as art spies or some shit. That puts it in line with views of a smash like 2015’s Furious 7 — if nothing else a model of famous people doing crazy shit in cool places — which saw about 188 million tickets sold. But ticket sales leave receipts that extremely diligent people can tally up. They can be manipulated like anything else but they’re more concrete than a “viewing hour”, a metric of time maintained by the company that owns the movie and the medium it’s watched through. Who says Netflix’s new movie had 330 million viewing hours? Netflix did.

And notice how not even Netflix is making Looper’s calculations to get full movie views. A “viewing hour” clearly doesn’t translate into watching the whole movie, although as a metric it’s actually better than Netflix’s infamous model from previous years, in which watching a movie or TV episode for two minutes counted as a “view” of that content. Netflix phased that out last year just in time for Red Notice’s numbers but I decided to watched the movie’s first two minutes to confirm its existence and count it as viewed because they should have their dumb fucking ideas turned around on them. Netflix promoted the movie with heavily green-screened action and actors allegedly interacting with each other while rarely sharing the frame; its opening credits intermingle fake stock footage about the mystery of Cleopatra’s legendary jeweled eggs and a shadowy figure creating a facsimile of one such ovoid. It was technically proficient, admittedly enticing, and no humans were visible.

In the first two minutes of Salesmen, actual human Corey Rodrigues drives to a house in the Boston suburbs and gets out of his car with a vacuum cleaner in his hand and an untrustworthy yet charming grin on his face. He and fellow salesmen Orlando Baxter and Will Noonan (all three helped write the movie and use their real names for their characters) are trying to talk their way into homes and into sales, they’re pretty good at it for the most part. The 80-minute movie follows them through various professional and personal issues — Orlando goes through a slump as a new saleswoman starts making bank, Corey begins a relationship with Orlando’s poetry teacher, Will studies for the bar to impress his dying father and take over the family firm. There isn’t a lot of plot to speak up, but all of these converge around the new sales object that is doing an increasingly brisk trade — “The Life Tendrils,” a book that describes how celebrities are lizard people using TikToks to hypnotize children, among other revelations. It’s written by a local man who generally wears bathrobes and nothing else and has an insistent, cultish charm of his own; podcaster Stavros Halkias is a natural at depicting a silver-tongued pervert.

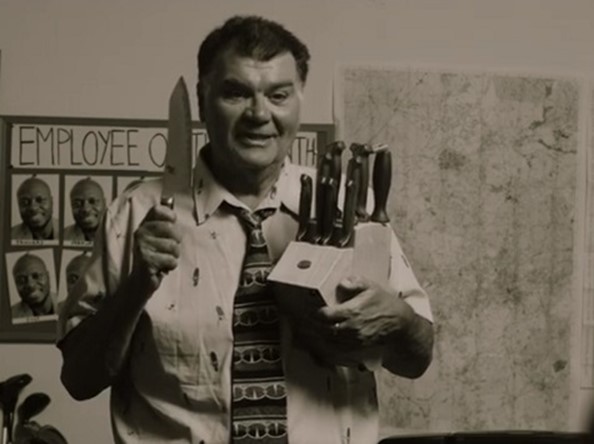

Like Red Notice, Salesmen was also produced during the pandemic. Director and co-writer Luke Jarvis had previously made a few shorts (including the hilarious Rope-A-Dope, which also stars Rodrigues) but wanted to make a feature and figured no one else was going to give him the opportunity. It’s a backyard production, not a big-budget one. There are no blockbuster sequences in Salesmen but on the other hand everyone in it is really there and “there” is really real. The movie was shot in and around Boston and looks like it, local suburban architecture and a few city locations ground the movie’s airy plot. Jarvis shoots in a crisp black and white that likely saved a lot of money but doesn’t look cheap, and he uses editing and framing to punch up gags. The script is funny (a local town gets turned into an extremely funny call-back punchline at one point) but is made even better by the actors’ delivery — a lot of stand-up comics make appearances and a guy like Brad Mastrangelo brings an extra oomph to a pickup line like “Do you want to see the biggest houseboat in Boston?”

“You are the last gasp of a dying society, you are commerce — do you even understand any of this?,” says another comic, Tony V, speaking as the hoarse and beleaguered manager of the salesmen (and woman). Salesmen’s great strength is to not believe any of that, to embrace its status as hangout flick and its recognition of small pleasures instead of life lessons. The salesmen discuss getting “real” jobs at one point and disdain the idea of a work life full of “e-mails and long conversations about Netflix shows I’ve never watched.” “Maybe there’s more to life than selling stuff and drinking beer, I don’t know, but at least it’s an honest living,” Will declares.

What bugs me most about Netflix’s numbers is how they’re just taken as fact, as if massive tech companies have not been dishonestly manipulating their figures and their data whenever they feel like it to blow up their bottom lines. A movie becomes an accumulation of hours that are allegedly watched but not actually verified by outsiders and we all just shrug. It’s a living of acquiescence, not honesty. Salesmen is now available on Amazon but the only way it could be watched last year, as far as I know, was through my north of Boston town’s film festival. Like many festivals in 2021 it was held virtually, making Salesmen another streaming movie with unclear numbers of viewers. Although there was at least one other person who watched it, a friendly older lady who was one of the festival’s organizers and who interviewed Jarvis (over Zoom, of course) about the movie and how he made it. She was a big fan! The interview played after the screening I downloaded and it was a nice moment of connection, that actual people made and watched what I just saw, a movie that didn’t have stars and stunts but still made me laugh a lot.

But if I’m viewing Netflix movies through one of their flawed metrics, maybe I should embrace the dishonesty and uncertainty of their promotion. Numbers not being real can be what the Chinese call a crisitunity if used in the right way. Did you know that 500 million people have seen this new movie Salesmen? That’s 4.5 billion hours of entertainment! You’re missing out, better watch it so you know what everyone else is talking about. The numbers don’t lie.