Movies talk to each other. What did the films of 2020 have to say? This is a look at how two movies from the past year tackle similar subjects in different ways. Be warned: SPOILERS for Bill And Ted Face The Music and Nomadland, as well as Convoy and Knightriders, follow.

This is a bad time. We’re under attack, we can’t see our enemies, we have nowhere to go, we are dying. We turn to art and we get algorithms. Is it even worth fighting back? But during all this there are still movies talking, new and old, about times that could be better.

Besides, bad times are nothing new. Back in the late 70s, for instance, gas prices were through the roof and you had to drive 55 with smokeys ready to pounce if you went over the line or weighed over the limit. This is the situation outlined in C.W. McCall’s smash novelty song “Convoy,” describing how a trucker named Rubber Duck leads an increasing, well, you know, across the U.S., the story told in the CB lingo of truckers themselves. The song was huge, as was the mythology of trucking in general, so of course a movie had to be made — producers wouldn’t let that valuable intellectual property with high brand recognition not be monetized for content.

Sam Peckinpah was brought in to direct this tale of discontents in the West, but he apparently was drinking even more than usual and his friend James Coburn wound up stepping in to shoot quite a bit. Peckinpah went over budget and submitted a 220-minute cut, the suits cut it down to 100 minutes and froze Peckinpah out of Hollywood for nearly the rest of his life. But that edit job was a hit! It made four times that overextended budget, despite generally middling reviews, like the notice in Variety: “Sam Peckinpah’s ‘Convoy’ starts out as ‘Smokey And The Bandit,’ segues into either ‘Moby Dick’ or ‘Les Miserables,’ and ends in the usual script confusion and disarray, the whole stew peppered with the vulgar excess of random truck crashes and miscellaneous destruction.”

There is no accounting for taste, but this sounds incredible to me. Le Miz with truckers crashing all over the place! And it’s not inaccurate, the movie is indeed messy, but its mercenary nature and final version contain the warmth and vitality of Peckinpah’s foolishly overlooked Junior Bonner. Like that movie, it has nods to The Wild Bunch — another joyous co-ed shower and the presence of Ernest Borgnine being the big tells, with Borgnine as a sadistic sheriff, a modern-day Dutch, on the trail of the outlaw truckers. Kris Kristofferson as the Duck is a reluctant Pike with his own gang — fellow truckers Franklin Ajaye and Madge Sinclair, Black actors Peckinpah purposefully cast in their roles as Spider Mike and Widow Woman, as well as the indispensable Burt Young as Pig Pen. And their convoy picks up more and more people — other truckers, Jesus Freaks (as per the lyrics of the song itself) and anyone who’s down for a good time, like one good old boy explains to a confused journalist:

“Sir, I wonder if I could ask you why you’re in this convoy with the Rubber Duck.”

“Well, I’m just along to kick ass and for the ride.”

“Yeah, but, well, uh, surely you must have some kind of personal grievance against the laws of this state?”

“No, I just like kickin’ ass.”

This all gets started because of a very personal grievance against the state — Borgnine and another cop start beating on Ajaye at a truck stop because they are racist shitbags and the other truckers kick the shit out of them instead. But it keeps going and going with people who have no connection to this, headed from Arizona toward the Mexican border, with politicians trying to exploit the uprising despite not knowing its language. Where the convoy is going is uncertain, what it wants is unclear. But in its motion, it’s become a world unto itself where anyone with a motor can join in.

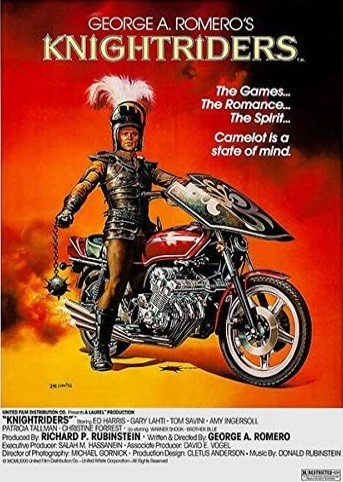

I probably would’ve watched Convoy at some point anyway, but I had a lot of time on my hands last year to poke around through streaming services and dig up gems. I came across George Romero’s 1981 film Knightriders after scrolling through a list of at least 150 movies in Shout TV’s “drama” section and suddenly my journey that night was over. It’s another movie about some dissatisfied Americans and their machines, but instead of truckers led by a reluctant rebel the motorcycle-mounted chevaliers making their way across western Pennsylvania are ruled over by a confident and perhaps overzealous king in Ed Harris’s Billy. The group is a functioning mini-society (its Merlin has a medical degree, useful for patching up wounded warriors) that is Ren Faire in its food and music and charging of admission for visitors but holds its jousts via motorcycle, and it too runs afoul of asshole cops who beat up some of its members and force the group out of town. But the larger threat is the society they’ve pulled away from — an event promoter is sniffing around, looking to represent them for bigger gigs, and skilled knight Morgan (Romero regular and gore god Tom Savini) and his friends are interested.

Convoy has the momentum of the chase, at two and a half hours Knightriders is more relaxed. The opening section alone, showing a typical fair day, runs at least 30 minutes and shows why people would live in this weird world with its anti-modern hierarchy and relative lack of technology. It’s a place where they can be free, if they want to. An obviously closeted bard snaps at the group for constantly teasing him about being gay, and he’s told it’s because he isn’t acting on who he is — one of the knights is an out butch lesbian and no one craps on her because she’s honest with herself and her society. This may not be the most enlightened way of looking at things but when the bard quits pretending and finally reaches out to a fellow musician he’s been eyeing, he finds love and a partner. The movie has the space for this because the world it depicts has a space for this. So many of Romero’s movies are about the inevitability of chaos overwhelming order and his zombie movies in particular slowly advance the argument that humans have their destruction coming. But here he sees and embraces the draw of a utopia, where people can make a better world.

Of course, a certain one true king of England had utopian plans and look what happened to him. Harris’ King Billy is purposefully unwilling to see how his queen and his top knight have eyes for each other and that is part of his refusal to acknowledge faults in the world that, as king, he must hold together every day. To acknowledge failure is to fail not just himself, but the dream he embodies. He’s already been smacked around by the cops and is dealing with wounds from jousts he won’t let himself lose — to lose is to lose position of authority, this monarchy plays fair — and finally takes one hit too many. But he refuses to relinquish power and Morgan and his crew leave with that tacky promoter to make money off the image and ideas Billy created. Disorganized and disillusioned, the rest of the group hunkers down at a fairground with their ill leader, who tried to force a world to be the “right” way and broke it instead.

Bill S. Preston, Esquire and Ted “Theodore” Logan never tried to change the world and that was a large part of why they are so beloved. Sure, they are told in previous movies Excellent Adventure and again in Bogus Journey by a man from the future that they will write a song that unites humanity, but they take this info with a most estimable equanimity. And while those movies involve travelling through time, visiting heaven and hell and conquering Death (via Melvining), they build to pit stops — passing a history test, winning a battle of the bands — on the way to that ultimate goal of peace and harmony. The latter movie concludes with some more ridiculous time travel and their band Wyld Stallyns playing a KISS cover of an obscure Christian rock song that, because of the goodwill and cheer of the movies and Alex Winter and Keanu Reeves’ godmode doofus performances, really does seem like it would teach the world to sing. Where would you go from here?

Nowhere but down. Bill And Ted Face The Music, which came out in 2020 after being worked on by Reeves and Winter and original creators/writers Chris Matheson and Ed Solomon for years, explains that the unifying song has yet to be written and that Bill and Ted have obsessed over their failure to do so, flailing in all directions (throat singing! Theremin!) as they attempt to realize their destiny. They’re a laughingstock to all but their daughters Thea (Samara Weaving) and Billie (Brigette Lundy-Paine), who like making music themselves via sampling and remixing and who have inherited their dads’ easygoing stoner charm. But when the two pairs find out that unless that special song is written in an hour, the entire universe will collapse because of Reasons, they spring into action.

Create utopia for all or see all annihilated — these are higher stakes than the first two movies and they have that curious empty heft such stakes often do, there’s even a damn Giant Death Cloud that wandered over from a comic book movie to threaten everyone here. And the prophecy of the promised song now says it will be written “by Preston and Logan,” a retcon that is fine but also is a loophole you could drive a tour bus through and waiting for the characters to catch on to that is a bit of a drag. Fortunately, Bill and Ted and Billie and Thea get up to some prime nonsense in the meantime. The latter pair, assuming their fathers have a song ready to go, zip through history to get a prime backing band — Jimi Hendrix, Louis Armstrong, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ling Lun, a cavewoman drummer — and this leads to a lot of fun on the level of the first movie, people out of time pinging off each other and yet rolling with the ridiculous conceit.

Bill and Ted, however, have not written their song and come up with the most brilliant idea in the movie — they swipe their old time machine and travel into the future to steal it from themselves. This of course does not go as planned and Reeves and Winter get to play increasingly shitty versions of Bill and Ted through time, constantly trying to trick their past selves and being thwarted (the way original Bill and Ted get around their future selves knowing what happens in the past is the funniest part of the movie). Where the heroes of Convoy and Knightriders hit the road to find what they need, the family of Face The Music journeys through time, raiding the past and future to create a perfect present. The girls return to that present with their crack backing band and they’re all immediately killed by a robot from the future (don’t ask) which is also trying to murder Bill and Ted. And to their immense credit, when Bill and Ted find out their daughters are dead, they drop everything and kill themselves via that same damn future robot in order to go to hell and rescue their kids. After all, they’ve been there before. They know how to get out.

At the beginning of Nomadland, out is the only direction its lead character can go. Frances McDormand’s Fern has in a very short period of time lost her husband to unknown causes and her house to the closure of the gypsum mine in Nevada where both of them and several hundred others worked. Now it’s a ghost town and Fern takes a few possessions and drives away in her new home, a camper van. She picks up tips from other older folks living the van life and following jobs where they pop up, from holiday shifts in an Amazon warehouse to picking potatoes in the Midwest to work at a tourist facility in the Badlands. There’s a lot of driving, for all of the trekking and trucking in Knightriders and Convoy Fern has the lot of them beat easy. She stays on the move and doesn’t talk a lot, but she does listen.

One of the people she listens to is an older gentleman named David with a bit of a crush on her; he’s played by David Strathairn, but everyone else in the movie is a real person “playing” a version of themselves. This is similar to the dynamic of writer/director/editor Chloe Zhao’s previous film, The Rider, about a Native cowboy facing down injury and the loss of his lifestyle, the lead and his family there were portraying their own story. Fern may be fictional but she’s based in fact, a book of the same name based off a magazine article called “The End of Retirement: When You Can’t Afford to Stop Working,” which looked specifically at those older Amazon workers in the “camperforce.” This is real, the movie quietly insists, harnessing the stories of its characters and their persistence like an idling engine, rumbling along but never going anywhere.

Fern sees a lot of beautiful sunsets and sunrises, incredible landscapes and weathered rocks, and also a lot of scut work, preparing food and cleaning out toilets for others before dealing with the bucket she has to shit in in her van. It’s a hard life that is day to day, and that seems to be what she wants. Nomadland is at its best observing Fern’s stubborn life in grief, her perseverance after the loss of someone who has left a hole in her existence. Sometimes a better world doesn’t seem possible. And a person can be in the world on her own terms.

The movie is less interested in the other side of that loss, though. How Fern loses not just a partner but a community because she loses her job, and how places are happy to give her and the other nomads work that becomes a necessary destination, a stop on the road to say hi before saying goodbye again. (And how that work is soft-pedaled — Fern’s time in an Amazon warehouse looks like hard but honest work with time to joke and eat with your co-workers, instead of a relentless machine where robots yell at the humans for every unproductive moment). So much time on the road again. At a gathering, the nomads cheerfully sing a reworked version of the Willie Nelson classic, but the constant music soundtracking Fern’s actual journeys is Ludovico Einaudi’s score of melancholy, rippling piano and it is utter dogshit, sounds whose highest aspiration is “tastefulness” and whose only habitat is a movie or a Pottery Barn for funeral urns. Fern listens to a transistor radio at one point while she’s parked but never tunes into angry AM talk or two for Tuesdays rock, let alone the sound of other drivers’ voices on something like a CB. Fern will listen to acquaintances tell their stories of metaphor and maybe lesson, but she and the movie are on a singular frequency.

Down in hell, Bill and Ted find their daughters and their band and ask Death, their old bassist who left the band after a fight (I’m not explaining this, watch Bogus Journey already) to let them back to Earth to save the universe. Our boys botch this but their daughters take over and, after they honestly but enthusiastically praise certain parts of the solo albums of the Grim Reaper (once again William Sadler is an off-kilter delight with his wounded pride) he agrees to spring everyone and rejoin the band. Where Bill and Ted have failed, their kids succeed — hmmm. And when the band is set to play the ultimate song that will stop Judgment Day instead of bringing it on, and Bill and Ted admit they don’t have it, Billie and Thea direct the musicians themselves, orchestrating and sampling the resulting sounds and patching everything together, and whaddaya know, “Preston and Logan” wind up creating the world-saving song after all. Musically it’s a thousand times better than Einaudi’s dreck but still more in the vein of Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros than good old KISS, so points off there (it’s hard to believe but of the movies discussed here, the best music goes to Convoy).

Musical taste aside, there’s still something a little off here. Matheson and Solomon can write Billie and Thea saving the day with their sampling skills but they don’t have the honest connection to this music in the same way they do to Bill and Ted’s headbanging rock. They’re on the outside, hoping for the best, which feels uncomfortably like Gen X praising activist teens on TikTok or whatever — well, we failed but at least the kids are here to fix what we fucked up, even if we don’t quite know how. Is it a gesture of respect or passing the buck? I think it might be the latter, but there’s still hope and love that makes it work in a sweet, generational way — after all, these guys raised the kids who saved the world, they must’ve done something right. Bill and Ted have their kids, but they also have to admit their dream, their reason for being, is dead so that others can continue the fight to make it real.

Death is more literal in Convoy and Knightriders, but there is hope here as well. The biker knights of the round table realize that they share their king’s ideals — even Morgan comes to understand that he’s just another act for the promoter to flog instead of a man among other men and women following a code — and return for one final tournament. And King Billy, still wounded (mortally so, perhaps) oversees this with grace and acceptance. When Morgan wins he gives him the crown and rides away. He makes a small stop to beat the everloving shit out of the cop who fucked with his crew at the beginning, just completely savages the dude at a restaurant not that dissimilar from the truck stop in Convoy, it owns so hard, but then he hits the road again. And hits a tractor trailer head on. The king is dead, by his own choice, and his subjects give him a somber funeral before riding out again to the next tournament, still unified under Morgan. Long live the king. Billy is gone but his dream, too, keeps going.

The Rubber Duck, like Billy, has premonitions of the end. While scheming officials set up a rowdy campsite for the convoy to stop at, the better to convince the Duck and his friends to become political props, he doesn’t bite on their offers, knowing they can’t give him what he wants. And meanwhile, crooked cops have caught and beat the shit out of Spider Mike in Texas, not too far from Mexico. The Duck and his original crew blast their rigs into the jail and free their buddy, but the Duck gets separated from the convoy — while he and the other truckers proclaim their independence from the Teamsters, it’s clear in the movie that they have the most power when united — and his truck is exploded and knocked into the Rio Grande when Borgnine’s sheriff unloads a machine gun at him, yet another Wild Bunch echo. There is a sad funeral and one more convoy hauling the coffin away, but as they go into Mexico, the Duck reveals he’s still alive (in the van of those Jesus Freaks, of course). He had to die to escape the land of the free but he’s with his buddies (and, uh, love interest Ali McGraw, who I have not mentioned at all yet somehow) and on the road, still pushing forward.

Nomadland is too restrained for a climax but it does build to a choice. Fern goes to visit David, who is living with his long-estranged son in the Pacific Northwest after the son became a dad himself. The extended family lives in a large, comfortable home and doesn’t have any immediately visible means of support (the movie’s lived-in details of road life and its small but brutal economies may backfire on it here, it’s hard not to wonder what the deal is with these people) but everything seems very cool and the family is more than open to Fern staying on. In The Rider, the protagonist forgoes the coolness of dying in action so he can stay with his family; here Fern leaves the possibility of a new stability to once again hit the road and drive into a new sunrise. It doesn’t feel false but it also doesn’t have the weight of the choice in The Rider. Or the choices in Convoy or Knightrider or Bill And Ted Face The Music, for that matter. The defining sacrifice of Nomadland happens before the movie starts, with a life and a livelihood lost, and this just continues down that path.

Does it mean something that the movies of struggle and defeat are made by guys who were and are looking at their time passing them by and the film that embraces acceptance of a hard existence is made by a woman whose career up until now has been filming people on the margins? I don’t know. I am a guy who is looking at his time passing him by, so I have a certain resonance with films covering that ground. And maybe I have a resonance with films of action as well. The Duck, King Billy, Bill and Ted are all fighting, in ways that are foolish and profound and often both at once. Nomadland is about just being along for the ride and it never once tries to kick ass.

You don’t have to change the world, of course, and you probably can’t. But because this world sucks shit, something that goes out of its way to tell me that’s all I have also sucks shit, no matter how pretty it looks and how profound it pretends acceptance is, especially when its acceptance is so carefully calibrated to not offend. Nomadland tastefully mounts its beauty, but these other movies are willing to fight for it and that fighting is beautiful too. I’m thinking of the beauty in Burt Young’s face as he gives other truckers shit over the CB while he picks up the convoy’s rear, his weathered mug dirty and smelly and as fundamentally incapable of dishonesty as a rock is of falling upward. I’m thinking of the beauty of King Billy and his people around a fire at the end of a long day, every person making a choice to be there because even if someone pissed them off today there’s always tomorrow and the world everyone is creating here is worth sticking with for one more night. I’m thinking of the ridiculous beauty of Jimi Hendrix in the 18th Century, happily blasting a Mozart sonata through a Marshall stack at the composer himself, and an irritated but intrigued Mozart finally jumping up from his harpsichord and going outside to figure out just what the hell is going on and getting sucked into a goddamn millennia-crossing supergroup trying to save the world.

I can see these people fighting together for a world that doesn’t exist on a screen in my isolated home and feel their connection in my bones a fuck of a lot more than I do a paean to the resignation and regret and “realism” of the world as it is today. Everyone has to stop fighting at some point but others can carry the struggle forward, maybe with some changes. Letting go so they can move on isn’t the same as giving up, and doing so is its own act of trust, a bridge that builds a small version of that better world. Of course, the time to let go might not be here yet. There’s still some road left to travel with friends, and if you don’t get where you’re going you can still be a lover and a fighter.