Movies talk to each other. What did the films of 2020 have to say? This is a look at how two movies from the past year tackle similar subjects in different ways. Be warned: SPOILERS for 2020’s The Invisible Man and To the Ends of the Earth follow.

How do you fight what you can’t see? And how do you fight what others can’t, or won’t, see? You’d have only yourself. Maybe not even that.

In writing and directing The Invisible Man, Leigh Whannell does give Elizabeth Moss’s protagonist, Cecilia, an important ally: The audience. Whannell sets up the movie with clear images — a terrified woman fleeing a home of few walls and many large windows, an eerie bodysuit that will obviously confer invisibility, a pursuer full of power and fury. Cecilia is obviously in danger here and though she escapes and her pursuer ex appears to kill himself shortly afterwards, when unsettling things start to happen (unexplained overdoses, divisive e-mails) we know that he’s ruining her life. (That, and the movie is called The Invisible Man, you know.) Instead of playing coy with Cecilia’s fear and sanity — is she under attack or just nuts? — Whannell plays fair.

And this opens up ambiguity in staging and atmosphere. Because while the audience is on Cecilia’s side, it is also tied to her perceptions. There is no Invisible Man-Cam, Predator-style, or scenes of the ex cackling in his lair. We only see what she sees and does not see, but with the added anxiety of watching Moss in Whannel’s wide shots and not-blurry-enough backgrounds, knowing that someone invisible could be there but not being sure about it. A lot of horror keeps the monster out of the frame, playing on the tension of when it will enter — here the monster could be anywhere, and watching is enough to play havoc with the nerves of Cecilia and the audience. It’s a disciplined, skillful trick, and that discipline and skill being aligned with the character’s own abilities makes the menace cut deeper.

Whannell also gooses this with invisible assaults and one is a magnificent setpiece of horror. Cecilia is eating dinner with her sister (briefly estranged because of those e-mails) at a restaurant, in full public view, and a knife floats into the air for the precise amount of time for Cecilia and the audience to register its existence before it slashes the sister’s throat and slots neatly into Cecilia’s hand. Even knowing who is really responsible, the images we are left with — a slaughtered woman, another woman’s hand on the knife — tell a story that’s hard to disbelieve. In one stroke, the monster destroys Cecilia’s most likely ally, the one who would believe her, and makes her the monster instead. Cecilia has been disbelieved all movie and now belief is turned against her when she is finally seen.

She fights back, of course, staging a clever break-out from the asylum she’s been committed to, and here Whannell overplays his hand. The invisible assailant tormenting Cecilia slaughters a bunch of guards in fluid yet inhuman shots of bodies snapped as cameras twist and rotate. It’s a cool style that Whannell deployed brilliantly in Upgrade, which was about a man letting his body be used as a machine, here it’s distracting and goes on for quite a while before Cecilia finally takes this invisible Terminator out. Only to find out it’s not the monster she thought it was — it’s her ex’s brother, and the ex himself magically re-appears, saying that brother kidnapped him. We’re back to the beginning, where Cecilia knows her tormentor is out there and the rest of the world doesn’t see it. But this time, she has a plan to take out the man ruining her life.

Atsuko Maeda does not have an invisible man trying to destroy her in To The Ends Of The Earth, but she does have several very visible men making her life difficult. Maeda, an actual pop star turned actor, plays Yoko, a would-be pop star working as the host of a Japanese travel program that is currently roaming around Uzbekistan, looking for “authentic” situations for her to experience on camera. The film opens with her going out into a manmade lake to try and catch a specific (and possibly fictional) fish, the surly local guide says the fish aren’t biting because a woman is in the boat.

Yoko and her small crew — cameraman, sound guy, writer/director and Uzbek translator/fixer — don’t have time to dwell on this for too long because it’s on to the next experience. The crew is constantly on the move, forgoing time in the country for clips of it — a quick lament about the miniscule amount of usable material compared to what was created is relatable to any editor — and if the lack of time means the local specialty hasn’t actually had time to cook before Yoko eats it, well, she’ll eat it on camera anyway and do so with a smile. Yoko is effervescent and cheerful when the camera is on but withdrawn when it is off. When the woman who was told to present that undercooked dish comes by later to offer Yoko the real thing, she turns it down.

Throughout the movie, Yoko pushes forward and retreats. In a lengthy scene as tense as anything in The Invisible Man, she gets on an extremely sketchy-looking version of the classic carnival ride The Zipper, a malignant multiple-rotation Ferris wheel, despite being likely too small to ride safely and despite how terrified and nauseating the machine makes her feel. She then does it twice more for extra camera angles. And when she’s off the clock, she forgoes eating with the crew to wander out through streets and alleys where locals side-eye her, where groups of men huddle under overpasses and glance at her as she quickly walks by, the camera following her but leaving space for the viewer to see the distance between her and these strangers and how easily it could be collapsed. Yoko is always being seen by others, but that connection doesn’t go beyond the visual. The movie’s frequent bursts of Uzbek dialogue are not subtitled, to reflect how Yoko doesn’t understand the language, but it’s unclear why she hasn’t bothered to learn even a few rudimentary phrases for this shoot. But Yoko ignores universal signs as well, routinely forsaking crosswalks to dart across multi-lane highways.

When she has downtime, Yoko has phone conversations with her firefighter boyfriend back in Japan — he is never heard and of course never seen, another invisible man. She longs to be back with him but she also longs for some kind of control while she’s thousands of miles away. One of her wanderings brings her face to face with a sad-looking goat, she convinces her crew to buy it and film her setting it free in the steppes outside the city. As the cameras roll, the goat’s former owner strolls up and grabs it back, pointing out the goat is free and therefore ready to be her property again. And anyway, it’s a foolish goat — setting it free out here means the wolves would get it. This argument doesn’t mean much to Yoko. If she doesn’t quite have a death wish, she’s pushing back on a life where her role is to be seen as a superficial host doing fake things. She wants to run with the wolves. But her courting of death, by car or imagined attack or horrible carnival ride, is a way of avoiding the life she has. Of not seeing where she is and what she can do there.

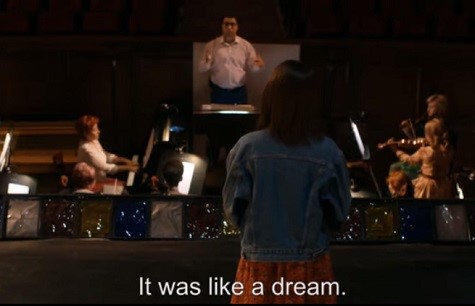

In the strangest sequence of the movie, Yoko hears a song and wanders into the Navoi Opera House in Tashkent, passing the theater’s artwork in its halls and architecture before coming out to see a lone woman singing on stage with an orchestra. And then Yoko herself is belting out the Edith Piaf standard “Hymme a l’amour,” until a security guard comes by and Yoko flees. Was that first woman there? Was Yoko, who dreams of a pop career, really singing or fantasizing? A little while later, the translator tells Yoko and the rest of the crew the history of the theater, how it was built during World War II in part by Japanese POWs who worked their own art into its friezes and walls. Their devotion to who they were in servitude is what made him interested in Japanese culture and led to his becoming a translator, he said. The bridge on the river Kwai ultimately served the enemy, this can serve something beyond captor and captive.

Earth was made as a joint production to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the opera house and 25 years of diplomatic relations between Japan and Uzbekistan, which sounds like a recipe for a travelogue of pablum, something in line with the worst of Yoko’s footage. But writer-director Kiyoshi Kurosawa treats it as something to be made with care, the way those POWs built a work of art that can still be seen today. Doing the work while staying true to who they are. The cameraman tells Yoko that he never planned on this job, he wanted to make movies. But now he makes films every week. Is that settling? Or seeing clearly?

For Cecilia, settling is not an option. She agrees to meet with her ex, and while Whannell lost the thread a bit with his ill-suited action he ties things together here. Because this is the first time in the whole movie we’ve actually spent time with the ex, Adrian (Oliver Jackson-Cohen), and his insidious charm works like an icepick, chipping away at the audience’s defenses. We know he’s a monster, we’ve seen the effects of his evil, but we have never seen him. And here he is, apologetic and sure and ready to move past all this. He’s in the flesh, undeniable. Seeing is believing. This is how they get away with it.

Cecilia herself almost falls for it. But she walks away. And then Adrian is the one with a knife in his hand, slashing his throat with a look of shock on his face. All of this is picked up by the home security cameras. What they don’t pick up is Cecilia recovering a spare invisibility suit. And while her cop friend finds her with that suit, he doesn’t stop her from taking it. The monster is dead, and it’s good he was killed. And hey, Cecilia taking the suit sets up a sequel. But there’s something unsettling about it. Cecilia uses the tool of her oppression to finally destroy her oppressor. So why is she holding onto it? Will she become the new unseen terror, haunting and hounding the abusive assholes of the world? This isn’t bad on its face, but when you can’t be seen you become less than a person. Having that done to you is a crime, choosing that for yourself seems like a mistake, a way for you to disappear.

After her opera house interlude, Yoko takes a camera to an off-limits area (her consistent pushing of boundaries is if nothing else a great journalistic impulse, she does have a knack for this work), leading the local police to chase her. After fleeing in fear, she’s finally caught and taken before the police chief, who admonishes her for not even waiting to talk to the cops. For this Westerner who has extremely strong opinions about filming in public and the martinets who try and stop it, this is the one note of the movie that rang false and possibly a sop to the host country. But it’s outweighed by the simple decency of the chief hooking up the wifi and leaving the room when word comes in that a major fire in Japan has killed several people, giving Yoko the space to possibly deal with tragedy. Finally she’s able to make a connection — her boyfriend is OK. Half of the crew goes back to Japan start working on this new story. But Yoko stays behind. The Uzbekistan segment she’s been working on won’t complete itself.

Yoko goes back to that lake and that asshole fisherman to try and finish the segment, but the fish are still not biting. And another local mentions that there’s a creature that lives in the mountains that’s just as rare as the fish and Yoko makes the call to go search for it instead. She and the diminished crew trek away, off in the wilderness where there’s no plan for the next shoot, just taking a chance on something that will probably be nothing. As Yoko goes on ahead, she sees that goat she wanted to set free. And she starts to sing.

Kurosawa’s Cure ends with a moment of action that can be read in two ways, one harmless and one murderous. It is up to the viewer to decide, but as Babalugats points out in his excellent consideration of the film, having to make the decision is its own horror. Here, Kurosawa ends with a statement that can be read in several ways. It could be a dream and it could be a hope, but I think it’s real even if it’s not actually happening. It’s the song of someone seeing herself, maybe for the first time, as someone able to love and to be loved.