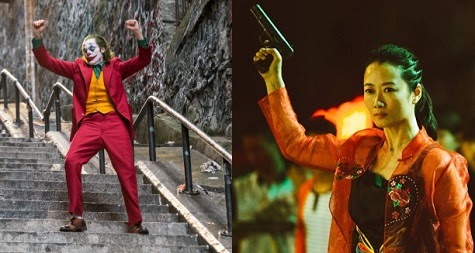

Movies talk to each other. What did the films of 2019 have to say? This is a look at how two movies from the past year tackle similar subjects in different ways. Be warned: SPOILERS for Joker and Ash is Purest White follow.

When Zhao Qiao and Arthur Fleck step outside, they enter different worlds and different times. A gangster’s moll and a failed clown share little in general, and when one lives in 21st century China and the other in 1980s New York City (let’s not be coy), there’s even less of a link. Those singular identities are what they have in common, though, and how they forge those identities through worlds indifferent at best to singularity.

Qiao and Arthur both live outside of polite society, but while Arthur wants to get inside via a comedy career and acceptance by his talk show host idol, Qiao is quite content to live with her lover Bin as a gangster. Each is jolted out of these dreams by an attack and a gun – when a rival gang beats up Bin, Qiao fires his pistol into the air to frighten them away; and when Arthur is attacked by Sondheim-quoting yuppies on the subway, he kills two in self-defense and one in cold blood.

Polite society is not a fan of such violence, and actions that take a few seconds have consequences that spin out over miles and years. Provincial officials were willing to ignore Qiao and Bin’s low-level extortion and violence before but they crash down with the full power of the state when shots ring out. And when the state and its avatar, billionaire philanthropist/amateur politician Thomas Wayne, decry Arthur’s actions, Arthur starts to wonder why he should aspire to their world.

The first time we see Qiao in Ash Is Purest White is through a hand-held camera on a cramped bus full of weary travelers. She’s barely out of her teens, going somewhere in a century that has barely begun – it’s actually footage from a film director Jia Zhangke was shooting in the early 2000s, and while that relic quickly runs out the movie stays in that time period for its first third. Qiao and Bin casually rule the roost in the decaying mining city of Datong. The industry is dying but there are clubs and bars and gambling halls where young people can feel alive. Outside of society they’ve created their own world where Bin’s gun can fall on the dancehall floor during “YMCA” and the beat goes on while Qiao calmly puts it away. Qiao pulling the trigger on that gun later is a choice visible on her face for a few seconds – she does not fire at any person, but she knows she’s shooting that world dead.

And she takes the fall, insisting the unregistered gun is hers and getting a full five years while Bin serves a lesser sentence. Almost none of this prison time is shown, just enough to get the full weight of five years as punishment, away from everything and most importantly the one you love. When Qiao gets out Bin is gone, along with much of their generation. Everyone’s moved to a more bustling city that’s on the rise, literally, as the massive Three Gorges Dam project hikes the water level. It’s impersonal in the way of new buildings and indifferent especially to Qiao, who’s new and town and without friends. Everyone has jobs with the state now and no one, not even Bin, can spare time for a crook who did hers.

Penniless and friendless, Qiao doesn’t rely on society – she manipulates it and extorts it with no hesitation and a determination that doesn’t contain the possibility of doing otherwise. At one point Qiao is bureaucratically stymied by a functionary covering for a cowardly Bin and Qiao looks at the other woman like she is dead, not with a glare imparting death but the cold eyes of someone who sees an empty, worthless body before them. Society offers her nothing and she asks for nothing.

She starts grifting people herself, singling out guys on bachelor parties and pretending to be the sister of a woman they’ve knocked up demanding hush money – it doesn’t take too long for this to hit. And when a taxi motorcyclist suggests a quick fuck, she steals his ride and leaves him in the wilderness, telling the cops he tried to rape her and that they need to get in touch with Bin. When they finally meet, Bin says he’s moved beyond the old life, but won’t say he’s moved beyond her. That’s something Qiao has to say for him. And she takes her leave, for a long, strange train ride where she meets a man who says he’s going to hunt for UFOs and is looking for a partner. Qiao briefly joins up with him until he admits he’s just a schmuck who runs a convenience store, another guy without the fortitude to live on the outside. So she goes back to the province where the story began, to find what’s left of the gang in the city where she made a place for herself.

The first time we see Arthur in Joker, he’s getting the shit kicked out of him in a grotty alley by a bunch of teenagers who think (correctly) that it’s funny to beat up a sad-looking clown. The Gotham of the early 1980s is a shithole for many people, but it seems both specifically designed to oppress Arthur, unlike the more impersonal cruelty of Qiao’s modernizing China, and oddly unspecific outside of its references. Arthur has a social worker to give him Pills for his Medical Condition That Makes Him Laugh until this is stopped because of Budget Cuts, no further details provided in the story but plenty of grimy shots aping Taxi Driver to cover the gaps. News reports refer to “super rats,” a gnarly notion which movies from Graveyard Shift to The Princess Bride know must be shown in their full glory – here one gets a blink-and-you-miss-it cameo. More than that would a bit too substantial, in a comic-book way, for this comic book movie. It is crucial that the idea of a society in decay be vague and free-floating so that the anger against it feels also feels inchoate, formless yet powerful. Charles Willeford once said: Nothing is inchoate.

Fearless Leader Julius Kassendorf has made a good argument for Joker’s futzing with reality, that richer imagery generally indicates fantasy sequences, and that this is part of a criticism of Arthur’s anger and persecution. There are a few obvious fantasy sequences of Arthur wooing his neighbor that are explicated as such but other scenes in this mode are harder to grasp – Arthur does get beat up in the beginning, someone does shoot those musical yuppies, there is definitely a big clown riot at the end. And outside of Arthur’s perspective, there is plenty to indicate widespread dissatisfaction if not outright hate of the society so many Gothamites are trapped in while Wayne and people who don’t feel trapped view them as unfortunate at best or “clowns” at worst if they speak out. Qiao is the rare person who follows her own path. Here there are many people yearning to breathe free. But who will lead them?

Whether the movie is criticizing Arthur or not, it ties his power as a symbol of this resistance to his shift from being put-upon to doing some putting upon of his own. Ambiguities are raised – is Thomas Wayne his father or not? Is his terrible comedy just a bad joke or a way to actual fame? Is Arthur crazy or just mad? – only to be irrelevant in the face of action. The action of Arthur killing several people and nearly killing others of course, but also the action of Arthur whining about it the whole god damn time. A whiner makes noise so people pay attention and Arthur’s apotheosis is not his giving society “what it deserves” with a public execution on national TV, but going out in the street and being loved for it by a literally faceless mob.

Joaquin Phoenix plays Arthur with denuded body (his ribs are begging for the touch of a xylophone mallet) and twitchy limbs. He demands attention as much as Arthur himself does and in that way his acting is appropriate. Both Phoenix and Arthur are performers, Arthur’s stand-up is terrible (but not his fault! He needs his Pills for his Medical Condition) but it is him, choosing the glare of the spotlight and putting himself out there by his lonesome for everyone to see what he can do. Qiao is played by Zhao Tao, Jia’s longtime partner on and offscreen, and Zhao the actress does something different: She gets old and she holds back. The hair/makeup/costuming team does great work here – not by visibly “aging” Zhao up or down but by giving her the style in clothes and appearance that fit a person in her 20s through one in her 40s – and Zhao does the rest, seeming to age on camera with the inevitability of Ellar Coltrane in Boyhood, her movements slowing and her face giving less away. And while Arthur needs the stage, needs to send out what he has to say, Qiao for all her fierce independence is content in the flow of the audience. She dances to disco and listens with intent to a street performance and then to a large stage rendition of a cheeseball pop song. Despite following her own path, she is set to receive.

Society will not listen to Arthur, not that he really wants it to. “You wouldn’t get it,” he tells his second Black female social worker of the movie as he’s being locked away in Arkham Asylum, the place where all of Batman’s scariest bad guys go. And then we see him leave the interview room, blood coating his feet, before being chased by some (disorderly) orderlies. Is this murder another fantasy? I’m inclined to believe so, which makes it no less cowardly a closing scene. Arthur spends the movie killing people who, in his words, “deserve” it, and the movie looks to generate tension by aligning his rage with ours, against bullies and cowards and everyone who’s working to keep us down. A real joker would let this violent death, imagined or not, be the punchline. Here it’s a final reference, another image of prettily conceived violence, as Arthur runs out of the frame, with society’s law and order in pursuit. He’ll be caught, of course – what would a comedian be without an audience? It’s unclear whether society needs Arthur but he needs it, to push against and to be appalled at his pushing.

Qiao spends years in her former province running a gang of increasingly middle-aged dolts. Then, one day, Bin is dropped off at the snazzy new train station on the outskirts of the city, slowly modernizing like everything else. He’s in a wheelchair, bitter and unable to walk. Qiao takes care of him, integrates him into the gang and brooks no insult to what he is now. The break she made years ago has not been healed, but the bond they had before that, outside of society, is not something Qiao could or would deny. It’s not water under the bridge, or over the banks of a river with $50 billion of dam behind it. That’s how society would look at it but society can go pound rocks. Alex Chilton once said: I would be an outlaw for your love.

Bin and Qiao live together for a time, Bin slowly regaining the ability to walk but retaining his anger. And then one day he’s gone, leaving only a voicemail goodbye. Qiao walks outside and we see her on one of the CCTV cameras she’s had to install outside her gambling parlor, a static surveillance frame of her from behind that could not be more different than how we first saw her, through another person looking for her face, shifting and sliding on a bus moving with endless possibility. That was then and this is now and if her face shows anything it’s out of our view, out of the view of anyone looking from the outside. You wouldn’t get it.