Movies talk to each other. What did the films of 2018 have to say? This is a look at how two movies from the past year tackle similar subjects in different ways. Be warned: SPOILERS for both follow.

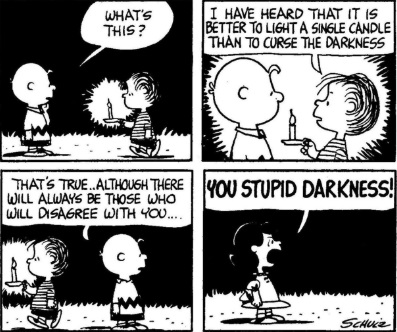

The first Paddington film, released in 2014, is sweet and charming without being cloying (Ben Whishaw’s voice is as essential to defining the character, albeit in a different way, as James Earl Jones’s is for Darth Vader). It takes its tone from its lead, who acts with politeness and persistence. He believes in an essential decency that requires exercise – and for the recalcitrant, a Hard Stare that is somehow more badass and threatening than the Scary Paddington jokes that predated the movie. Paddington 2 plays as an expansion of this and wisely resets nothing. The family that Paddington brought together at the end of the first movie might retain a few personal worries and misgivings but they have shared his decency and draw strength from it, in the way that one candle can light others.

So when Paddington is framed and accused of a crime he did not commit in the process of trying to find a birthday present for his aunt, his family does not question his innocence and instead gets to work helping him out, using the same polite persistence Paddington does. The world disbelieves them, is ready to consign Paddington to the darkness, but they push back. And Paddington, meanwhile, takes his attitude to prison. Prison is not ready for this. Hardened cons are no match for the small bear’s insistence on behaving with civility and making the most of a restricted situation while he waits for his family to free him.

Paddington is no Pollyanna, glossing over the bad to narrowly focus on the good, nor is he content to just hope. He takes the actions he can and ultimately — mistakenly believing his family is no longer helping him — he escapes with a few other inmates. But he does not join them in going on the run. He returns to the task of proving his innocence, which is merely a step toward his original goal of doing something kind for his aunt.

What makes this sing instead of slog is the gentle fun the movie pokes at Paddington, recognizing that his heart may be strong and his purpose true but his actual actions can miss the mark. Paddington will helpfully wash a window or courteously assist in the kitchen or lead a righteous chase astride a stalwart dog, and cause chaos well beyond his noble intent. These scenes revel in the details of things going wrong, there is a sense of amusement that someone meaning so well can screw up this badly, and it helps that Paddington himself often absorbs the harder knocks of these slapstick setpieces but constantly bounces back.

This gives more meaning to the final showdown between the dastardly villain and Paddington and his family – united at last, they make their way through a series of obstacles to save the day and their various talents let them ride atop the madness, if not control it. As before, this is filmed with an eye toward clearly delineated mayhem, but here the objects in motion – people, trains, balls, bears – are managed with purpose by a group in harmony with each other. This is similar to an earlier tableau of joy and whimsy, as Paddington imagines taking his aunt on a tour of London, the city reconfiguring itself as a pop-up book that shifts and surprises. It’s a wonderful animated sequence, but what really animates the scene is Paddington’s desire to see it brought to life, to give it to someone who could use some brightness in her life. The light radiates out of him.

Ito, the lead of The Night Comes For Us, is surrounded by darkness. He’s an elite assassin for the Triad and has just slaughtered almost an entire village, something he has definitely done before. But something breaks as he’s about to shoot a young girl – this is after he’s already murdered her parents – and he instead guns down the rest of his strike team, grabs the girl and flees back to his old gang in Jakarta. The Triad, predictably, is not amused, and sends waves of goons, killers, cops on the take and top-tier assassins led by Ito’s old friend Arian to take Ito and the girl down.

Our own Jake Gittes was critical of the movie’s overwhelming bleakness, noting how no one is even enjoying their ill-gotten gains. And the movie’s protagonists do not have righteousness or redemption on their side. Ito’s old gang, particularly the massive, gimpy heroin-addicted White Boy Bobby, does not immediately stick up for him in his time of trouble. They’re pissed he brought an unwinnable fight to their door. And yet they take their stand, partially out of anger at the Triad for screwing them over in the past and the opportunity to deny the organization something it wants. To curse at the darkness that would come for them anyway.

Paddington‘s action is rooted in good intent spiraling out of control with slapstick elegance. Night‘s furious fights are simpler – the desire to kill by any means necessary. Ito faces down goons in a butcher shop, which of course necessitates the use of various cleavers and knives, and meat hooks and the frozen carcasses themselves become weapons. He later tears through a warehouse of foot soldiers who happen to have a pool table – cues, balls and the slate of the table crack heads and break backs. White Boy Bobby and company smash their way through an entire apartment of goons, breaking household objects and using the pieces to gouge and slice. Iko Uwais, who plays Arian, also played the lead of The Raid and choreographed the stunts both there and here, but director Timo Tjahjanto focuses on spraying blood as much as snapping bone.

Paddington‘s action ultimately brings people together. Ito kills nearly everyone he sees. The carnage is total, and to what end? Commando, arguably the greatest Schwarzenegger action movie, has Arnold mowing down literally hundreds of bad guys in order to save a girl. But cartoonish tone aside, he’s also rescuing his own daughter, someone with whom he has an emotional bond, not a person who he personally has orphaned. For Ito, saving this one life unleashes an ocean of blood, and it certainly won’t save his own life or let him escape any Hell that awaits him in the next world. And it ultimately won’t stop the Triad from existing and hiring someone else to do the same dirty work Ito once did.

What Paddington the bear understands in his bones and what Ito realizes in a flash is that the action is what counts, and the action needs commitment. Paddington is an enlightened being who has very little barrier between being and doing, so even when intent and action diverge in slapstick the persistence of his character ultimately unifies them. He can let the darkness come close because he shines so brightly. Ito does not have that inner peace, and the harsh grace of Night says he will never get it and that he doesn’t need it to do one good thing in his life, even as doing that one good thing requires absorbing and inflicting pain over and over. It’s a hard road to go down and one that can only end one way, with Ito helping his charge escape before driving toward an unbeatable army unleashing inescapable hell at him. Ito steps on the gas and stares at his killers. He’s screaming.