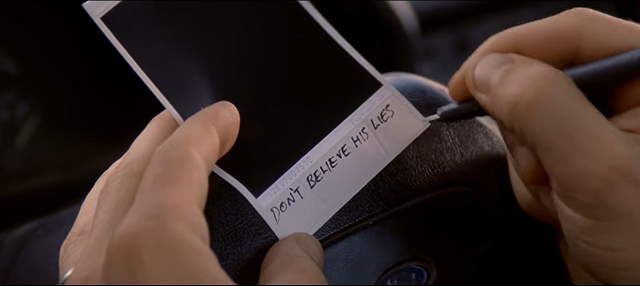

One great thing about art is that you can use it to see the difference between who you are now and who you were when you last witnessed it. I first watched Memento when I was sixteen, and I found myself identifying strongly with Leonard’s memory problems. Due to what was most likely ADHD or autism, I had an absolutely garbage memory that left me feeling as if I were floating through a sequence of disconnected incidents; I recognised my worldview in the anachronistic editing and the way both viewer and Leonard constantly had to get our bearings as to what was happening now (“I’m chasing him. No, he’s chasing me.”). I rewatched it for the first time at the age of thirty-one recently, and you would think that having a functioning memory would leave me less able to identify with the movie, but if anything, I saw how the movie had warped me further into Leonard. I remember that watching the movie inspired me to start setting alarms on my phone when I definitely needed to remember something later, which has slowly evolved into an entire system of external memory devices. What I took from the movie was the thought that my future and past selves could be considered a different person from myself entirely, someone who could be warned, advised, or listened to. As you might expect, my memory has improved – probably due to developing all these devices, most likely due to a range of things I’ve done to improve my health and happiness.

The idea that art can change us into better people is a popular topic here in 2022. People – mainly but not exclusively leftists, just to make things interesting after a generation of right-wingers did it – are interrogating art through the morality it’s perceived to be passing on. Is this work making us racist? Did I learn toxic behaviours about how to treat women from this comedy? Does this show adequately punish bad characters, or at least show us that what they’re doing is wrong? It’s also popular to say this is a fucking stupid way of interrogating art that infantalises the viewer, flattens the work, and flatters the preconceptions of the critic. Fundamentally, it’s an arrogant question to ask – how do people dumber than me react to this work*? And yet, I have right here a clear, specific case of a work of art inspiring me to commit a specific action that improved my mental health. In general, it’s been hypocritical of me to make fun of the idea that art should make us better when not only have I specifically sought out art to improve myself, I’ve even achieved that from time to time. Memento had exactly the effect that the people I often mock have wanted – I identified with the main character and improved myself through his example.

*I’m sure there’s a reason to care about what people dumber than me think, but I haven’t found it yet. The closest I’ve come is reading between the lines and seeing things they clearly didn’t.

There’s a famous phenomenon called the Scully Effect, where a generation of young women watched The X-Files, saw a woman competently performing scientific analysis – both literally in performing autopsies and medical analysis, and more generally voicing a skeptical and materialist counterpoint to Mulder’s dreamy-eyed theorising about the supernatural – and were inspired to go into either law enforcement or STEM fields. Acting as propaganda was not the goal of The X-Files, but it wasn’t not the goal either; Chris Carter intentionally chose to have the dreamy-eyed psychologist be male and the hard-nosed hard-science skeptic be female because he thought that was more original and interesting. He created an image that wasn’t there before and it replicated itself immeasurably. Outright propaganda only works on people who already agree with it or who want to be seen agreeing with it; it galvanises those who believe that they have something to gain from it.

By comparison, Memento and The X-Files genuinely planted a new idea in someone’s mind. They both had the intended effect of propaganda. What’s important is that achieving this maybe barely cracks the top five of the goals of either work; Memento is more concerned with existentialist questions whilst The X-Files is a series of short horror stories. On top of this, I would say that ‘fixing my shitty memory’ is pretty far down the list of things I love about Memento (though above its cinematography). I find myself thinking of how the time machine in Back To The Future was originally supposed to be a box before Bobs Zemeckis and Gale realised that kids everywhere would be climbing into and potentially locking themselves inside fridges imitation, motivating them to change it to a car (and then specifically to a Delorean, because they realised their mad scientist was kooky and out of touch). I think the conclusion here is that anyone looking at storytelling from a propagandist standpoint has to recognise that action ranks higher than principle or even consequence in terms of importance. You put a cool guy lecturing an idiot on Right and Wrong on your silver screen, what you’re probably gonna get is your intended idiots ignoring you and idiots on your side picking up on the lecturing.