The trajectory of Stan Brakhage’s approximately 50-year career moves from films he shot himself with a single camera to films he made entirely by painting or manipulating the film itself. There are a lot of works that do both, and there are still many camera-shot films in his later career. All his films, though, were made entirely by himself or with a few collaborators; he was one of the great inspirations in the pre-digital age for those who wanted film to be a solo rather than an industrial project. (Brakhage lived in Colorado most of his life, and two filmmakers he so inspired were Trey Parker and Matt Stone; they named South Park’s Stan in part as homage to Brakhage.) To my mind, Brakhage’s masterwork is 1987’s hand-painted The Dante Quartet, but the great work of his camera-shot films is 1971’s The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes. It’s the third panel of a triptych shot in Pittsburgh: Eyes was shot while Brakhage did a ride-along with police; Deus Ex was shot in a hospital; and The Act of Seeing. . . was shot in a morgue and shows only autopsies. (The title is the etymological meaning of “autopsy” and as we’ll see, a principle of method.)

If it was footage of autopsies and nothing more, it wouldn’t be worth discussing, but Brakhage uses all the resources of cinema here to make something unforgettable out of this. As a condition of filming, he was required not to show any identifiable faces on the corpses, but he goes farther than this: there are almost no faces here at all. He goes in close on the framing, looking at hands, scalpels, bone scissors, rulers, looking at the activity of people rather than the people themselves. He’s equally close at what they’re acting on, the fingers, scalps, breasts, bones, penises, feet, limbs, and organs of the bodies.

The 1971 film stock gives the colors here a vividness we don’t see much of anymore, especially when as the trend in so many films bends towards desaturated gray/green. There are colors here from all across the spectra of hue, saturation, and brightness, and they exist next to each other in a way that’s startling. I never knew our bodies had that much color in them. In one moment, neatly set up by some slow edits, Brakhage cuts to a scalpel slicing through dark skin to reveal a bright white layer of fat; the sudden appearance of that layer of blinding spongy white plays as a jump scare the equal of anything in horror. Going back to Noel Murray’s line that “horror is a genre made for formalists,” what’s powerful here is how Brakhage smuggles in a lot of formal effects while making everything look like the camera just happened to catch it.

Brakhage filmed this himself, as he usually did, with one handheld camera. Usually the involuntary motions of the camera in a Brakhage film are like brushstrokes: present and individuating but not defining. Here, though, the camera shakes more than usual because Brakhage shakes more than usual; he stated that he could barely get through filming, and if any children had been autopsied, he wouldn’t have made it at all. In some great examples of handheld camerawork (Husbands and Wives and The Shield come to mind), the camera can be shocked; here, the camera seems like it’s in a permanent state of terror. A steady fixed view wouldn’t have worked here, because it would place us too much on the side of the coroners; keeping the extreme subjectivity of the camera sets up a difference between what they’re doing, what they’re doing it to, and what we’re seeing.

That sets up the what could be called the organizing principle of The Act of Seeing. . ., contrast, all through the film: between the textures and colors of flesh, between motion and immobility, between agents and objects, between the hard geometric lines of incisions and the curves of bodies, between clothing and nakedness, between bodies and empty spaces within them, between the clear rituals of the coroners and the shakiness of Brakhage holding the camera, and of course these all come down to one fundamental contrast, between the dead and the living.

This is a silent film, so we see all of this with no explanation as to what’s happening; at several points we could be almost be watching an instructional film with the sound off. Most of Brakhage’s films were silent; as I’ve mentioned before, he felt that adding music destroyed the continuity of his images. While that’s true, there’s no Brakhage film that’s as necessarily silent as this one. Had he synced up sound and image, he would have destroyed continuity rather than created it, forcing a break in sound at every edit. More than that, the silence adds one more layer of contrast: we see all this activity, everything that people are doing, but hear nothing. This isn’t just about the act of seeing with one’s own eyes, it’s about being trapped in that seeing, with nothing to explain and nowhere to look away.

There may be no better editor in the history of film than Stan Brakhage; certainly I can’t think of anyone whose films depend on editing the way his do. (For example, The Dante Quartet cuts according to rhythm of Baroque music, fast/slow/fast.) In editing this, he said he couldn’t find a theory about it; he couldn’t find a way to shape the images to some larger point. You can see deliberate, mathematical patterns of editing in works like Cat’s Cradle and 23rd Psalm Branch, but not here. The Act of Seeing. . . feels more organic than that; more than in any other film by him or possibly anyone else, the edits and jittery camera feel like a consciousness reacting, not able to look away–in fact some edits suddenly look closer at what it doesn’t want to see. Also, Brakhage uses no superimpositions, negative images, colored frames, on-screen text, or any of the other devices from his other filmed works. There’s only the footage he shot and how he edits it, only what he saw and how he saw it. It’s his acceptance of his own instinct that gives The Act of Seeing. . . so much of its power.

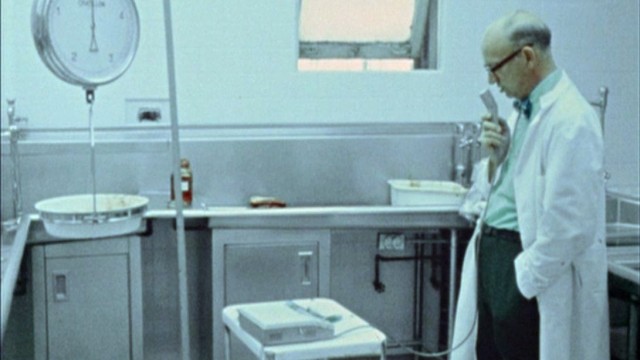

Not having an elaborate theoretical construct for the overall edit, Brakhage opted for something obvious: you could call this a collaged narrative, where several autopsies are put together in the sequence of a single one. He begins with one body getting palpated (speaking of textures, there’s a distinct early moment when a coroner presses his finger into the skin and the depression doesn’t go away) and then moves through the process of cutting, removing, and slicing organs. At several points he shows us bodies covered in sheets and wheeled away–it’s really a motif–and at one point a hallway full of them (another distinct moment, the kind documentarians live for: shot of a wastebucket stacked on a body). This narrative conveys both the feeling of a single day at the office for the workers and of a deepening horror as the bodies get excavated for us. He concludes with a shot of closing doors and of a coroner in an empty, antiseptic room speaking notes into a recorder, and after the half hour we’ve just seen, it seems nothing could be more surprising than that, the crammed, busy, colorful, horrific frame replaced with an ordinary room and an ordinary act. Again, it communicates how ordinary this is for the people who work there, but not for us; it’s also the only shot I could find that didn’t need a content warning.

Among contemporary filmmakers, David Fincher has picked up a lot from Brakhage; the credits from Seven explicitly homage Brakhage’s film Mothlight. You can really see the influence, unsurprisingly, in the autopsy scene in Alien³, as Ripley has to watch Newt get cut apart. Fincher understood what Brakhage showed, that it really is about the act of seeing: he frames and edits the scene according to what Ripley sees, not according to what is happening; Fincher cuts to give a sense of a mind trying not to see and not to process what it’s perceiving. It’s both tense and almost unbearably moving, and it was for many of us the first indication that Fincher would become a great director, someone who could incorporate radical techniques into mainstream filmmaking. (The practice of witnessing, although not this style of filming it, would come back in Seven and Zodiac.)

The Act of Seeing. . . creates a brutal level of identification, not empathy, because we can all recognize; it plays off the presence of death, something that’s there for all of us. It plays off the Tom Sawyerish fantasy of being present at your own funeral in the most brutal way. You want to be present after you’re dead? Here’s what it will look like; here is what your body will become. Watch as all your thoughts and memories and emotions get scooped out of the skull. Here is your beautiful, expressive face; watch as your scalp gets peeled off the skull and folded over it. (This doesn’t look easy.) Here is your torso, your strength; watch as a pair of scissors cuts through the ribs, one by one. Here’s what your body will become, a decaying object to be sliced up and placed in jars as part of someone else’s workday, and left out in a hallway with the garbage. Here is what you will become, what we will all become; this film is a thirty-minute demonstration of the lines from Joseph Heller’s Catch-22:

Man was matter, that was Snowden’s secret. Drop him out a window and he’ll fall. Set fire to him and he’ll burn. Bury him and he’ll rot, like other kinds of garbage. The spirit gone, man is garbage. That was Snowden’s secret. Ripeness was all.

I believe in a life after death: not a consciousness, not in action, but a life; and this is not an argument but a belief. It’s not rational, so this belief cannot be denied through rational means. The Act of Seeing. . . is one of only three works I know that genuinely shakes me in this belief and has at times made me doubt it; the other two are Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s episode “The Body” and Dmitri Shostakovich’s 14th symphony, the greatest works on the unalterable finality of death. They are in the long tradition of the reminders of death that began with the skull inscribed in the floor of palaces, telling the rulers that they were mortal, and no amount of power, righteousness, or holiness could avoid that, could buy them a life one second longer than its appointed span. That tradition has come down through the ages to us as the horror genre. Some of those works, of course, gives us a good, safe scare and allow us to avoid that sense of death. Other, great, enduring works of horror (Seven, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and John Carpenter’s The Thing come to mind) confront that sense head-on; we’re not relieved by these works but deeply shaken because they remind us of our terrible fragility and finitude. In its utterly unsparing pursuit of that reminder, The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes may be the greatest horror film ever made.