The first music you hear is the Grateful Dead covering “Death Don’t Have No Mercy” by the Reverend Gary Davis. One of the band’s many signature songs over the years, it’s a gravely serious warning that the end comes for everyone, and to be ready for that day of reckoning. But the Dead take a different conclusion from the song—better have fun while it lasts, because, as they sing in the elegantly downbeat song, “Box of Rain,” “Such a long, long time to be gone/And a short time to be there.”

Long Strange Trip documents how this cosmic philosophy played out for the Dead. Directed by Amir Bar-Lev, it features interviews with members of the band, support crew, and journalists—including, significantly, Dennis McNally, who wrote A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History Of The Grateful Dead, which Bar-Lev takes as a guiding text.

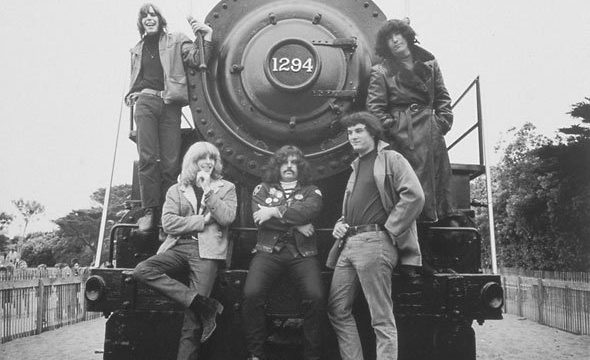

We start with the dawn of the Dead. Jerry Garcia, guitar player and vocalist, teams up with nonperforming lyricist Robert Hunter. Garcia recruits a gutbucket blues singer and organ player, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, to act as a frontperson when needed. Phil Lesh, an avant-garde composer to whom Garcia assigns bass playing duties, Bob Weir, on rhythm guitar, and Bill Kreutzmann, on drums, form the nucleus. Later, Mickey Hart plays drums alongside Kruetzmann, doubling the rhythmic pulse.

Inspired by Jack Kerouac’s writing about his freewheeling friend, Neal Cassady, Garcia and Hunter pick up the Beat ethos of hitting the road in search of kicks. They meet Ken Kesey and his anarchic comrades, the Merry Pranksters, of whom Cassady is a member (their encounters with Cassady are immortalized in their epic freak out, “The Other One.”) They become the house band for Kesey’s Acid Tests, where people took LSD. Under the influence, traditional boundaries in blues, soul, rock, and bluegrass music dissolve for the Dead.

Living, playing, and tripping together, they tighten up. Listen to their blazing workout on “Viola Lee Blues,” performed on February 2, 1968 (the exact date, as any Dead devotee would tell you, is important), and you witness how Garcia took the practice, in bluegrass music, of the players communicating with each other while performing, and implemented it in an electric ensemble.

Living, playing, and tripping together, they tighten up. Listen to their blazing workout on “Viola Lee Blues,” performed on February 2, 1968 (the exact date, as any Dead devotee would tell you, is important), and you witness how Garcia took the practice, in bluegrass music, of the players communicating with each other while performing, and implemented it in an electric ensemble.

The film works, for the uninitiated, as a comprehensive chronicle of a band that is at the heart of Americana. And it also works for people who find in their music moments of incandescent beauty—such as myself—as an experience that few, with the possible exception of those in the Dead’s inner circle, have had. Although divided, somewhat awkwardly, into six episodes, Long Strange Trip is best watched in one sitting, with one or more breaks, to get the highest of the highs and lowest of the lows.

Regarding themselves as the musical counterparts of the Pranksters, the Dead’s initial attempts to capture their high-wire improvisations in the studio are interesting, but, from the perspective of Warner Brothers, the record label that had the admirable courage of signing them, unsuccessful. The Dead broke every rule—even some they didn’t know—of studio recording. The record label issued memos that spelled out their unhappiness; the band’s response, at least once—as depicted in the film—was to scribble “FUCK YOU!” on the cover sheet and send it back.

Garcia then got the idea, much to the record label’s relief, to make more traditional records. We see rehearsal footage of his coaching Weir and Lesh on vocal harmonies modeled after their massively successful contemporaries, Crosby, Stills, and Nash. American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead became the first two parts of the essential commercially-recorded Dead trilogy. They were melancholy country-rock albums—featuring Garcia on pedal steel guitar and banjo—that yielded some of their best and most familiar songs: “Uncle John’s Band,” “Ripple,” “Casey Jones,” “Truckin’.”

These are the songs you’re most likely to hear on the radio. Their success prompted the record label to fund a Western European tour, resulting in the three-record live album, Europe ’72, the final part of the trilogy. Europe ’72 arguably captures the Dead at their peak of creativity.

We also see footage of them playing “Bird Song” at a famous show in Venuta, Oregon in August 27, 1972. During the show, the band and the audience dealt with 100 degree-plus temperatures—making the experience even more dreamlike.

For me, 1972 was the year of the Dead, and “Bird Song” is the one song I’d recommend anyone to hear by the band. It was written for the deceased Janis Joplin, who had been romantically involved with Pigpen. I’d doubt you wouldn’t be moved by Garcia’s lyrical guitar work and the cresting rhythms of their soulful farewell to a fallen comrade.

Then in 1973 Pigpen drank himself to death. The film, to its credit, doesn’t treat his passing lightly. Gone forever was a standard part of shows: Pigpen getting the crowd on its feet with a climactic rendition of “Turn On Your Lovelight.”

Then in 1973 Pigpen drank himself to death. The film, to its credit, doesn’t treat his passing lightly. Gone forever was a standard part of shows: Pigpen getting the crowd on its feet with a climactic rendition of “Turn On Your Lovelight.”

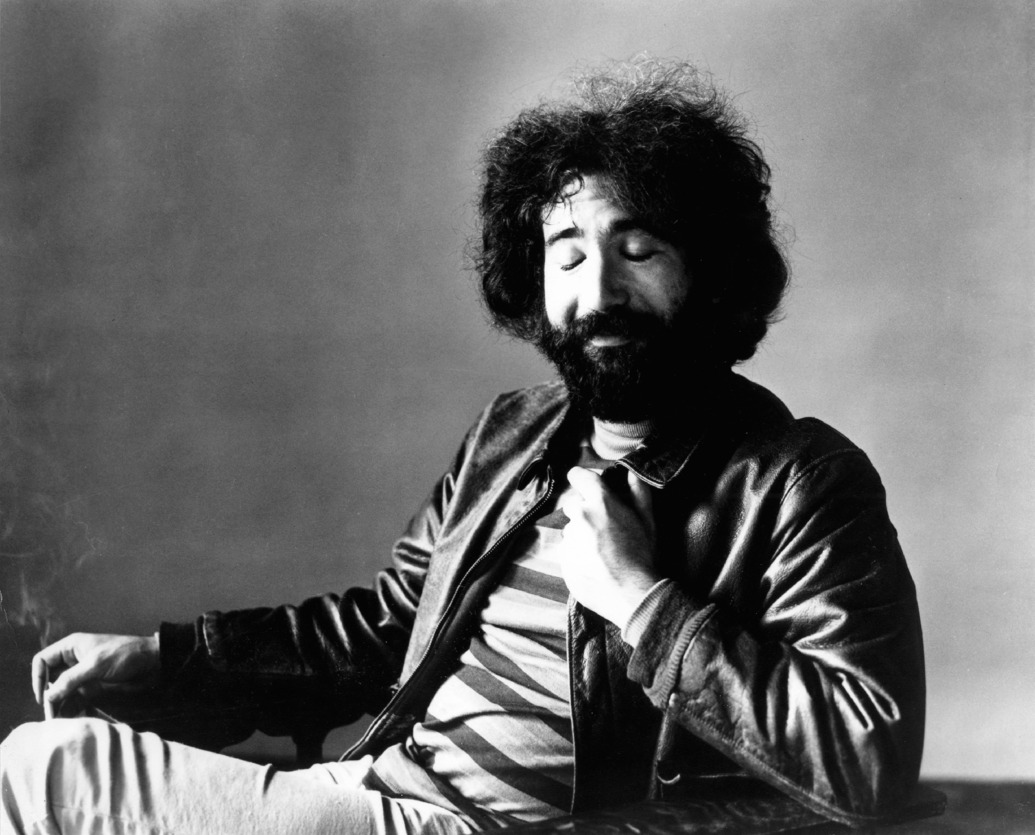

The darkness around the Dead increased in 1974. It wasn’t a good year for many rock bands as hard drugs had entered the scene. Cocaine made people self-absorbed—its manic energy was soulless. Heroin, sometimes used to come down from a cocaine high, killed people.

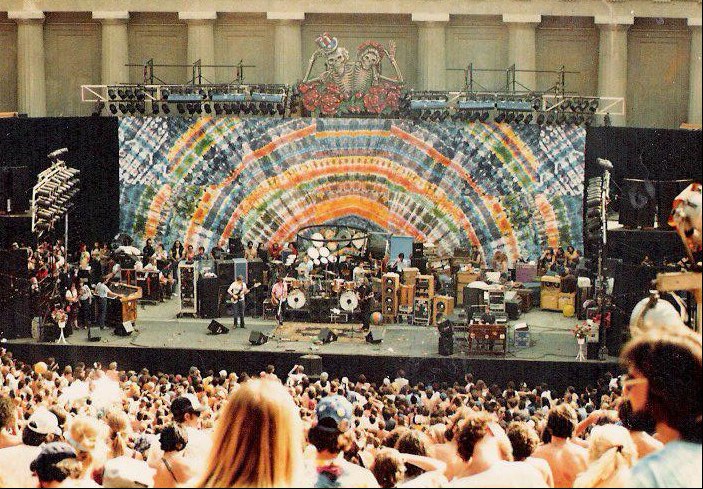

These drugs became part of the paradox that was the Dead. The road crew and musicians used cocaine to stay awake and alert through the endless touring—every show in 1974 required setting up a massive PA system, dubbed The Wall of Sound. The Dead’s caring about their audiences’ experiencing the most fantastic sound possible—once more pushing everything to the limit—came at the cost of caring about themselves.

Garcia sunk into using heroin. An incredibly thoughtful person, as any interview with him will attest, he nevertheless refused to deal with any questions about moral responsibility. Again, the film does not shy away from this subject—all but having “JUNKIE” in flashing neon lights with an arrow pointing to Garcia. With Pigpen gone, Garcia was regarded as the bandleader, and looked for a way of avoiding the job at every chance.

As a virtuoso on guitar, Garcia could be using heroin and still sound rather good. Yet he could also sound zoned out, depending on what song and what show you saw or heard. For fans of the Dead, every show was different, thus worth attending.

As a virtuoso on guitar, Garcia could be using heroin and still sound rather good. Yet he could also sound zoned out, depending on what song and what show you saw or heard. For fans of the Dead, every show was different, thus worth attending.

Hardcore devotees of the band who followed the band on tour were called Dead Heads, and the film, at this point, goes in a sociological direction, focusing on the experiences of the band’s fans. Al Franken shows up to talk about his tape collection of recorded Dead shows—the band took the unusual position of allowing their shows to be taped and the tapes to be shared.

I find it rather telling that in the closing episodes the music of the Dead is rarely mentioned: the ritualistic elements of going to a Dead show had, by the 80s, overshadowed the actual performance, what had become mostly formulaic jamming. The band’s growing popularity—which perhaps suggested an underground response to the social conservatism of the Reagan era—did little to slow down Garcia’s downward spiral.

Still the Dead kept on going into the 90s. We see a chilling image of Garcia, now a ravaged older man with white hair singing “Death Don’t Have No Mercy.” His time was up. He died in 1995.

Long Strange Trip has to end on a downer—there’s simply no other way of telling the story. But what a story.