Collateral stands as the best of Michael Mann’s ongoing digital period, which may conclude with his Enzo Ferrari biopic, currently in production. Collateral is many things with many virtues: a stripped-down genre picture; a continuing education in how to make an action scene and an action movie; an acting recital for the duo of Tom Cruise and Jamie Foxx, with elegant arabesques from another deep Mann supporting cast (Javier Bardem, Klea Scott, Bruce McGill, Peter Berg, Mark Ruffalo, Barry Shabaka Henley). Alongside all these things, though, and resonating with each, it’s a portrayal of the spaces of Los Angeles, physical and emotional; without sacrificing one moment of intensity, Mann crafts a feeling that occasionally made itself known in his earlier films but now pervades everything, a part of the ground that now becomes a figure. If this is a film where Los Angeles plays itself, Mann coaxes a lonely and longing performance out of it.

In terms of plot, Collateral has its own kind of isolation, what Mann described as only the third act of a larger story. A moderate-level drug cartel player is about to be indicted in Los Angeles; for some unspecified time, the cartel has been gathering information about witnesses and attorneys. Hitman Vincent (Cruise) arrives in L. A. (in a wonderful touch, it’s Jason Statham who hands off his bag of professional goodies in the first scene) to kill five of them in a single night, and he gets cabbie Max (Foxx) to drive him. All the details–the crimes, how the different players are involved, how they were tracked down, Vincent’s background–get ignored. It’s a beautifully pulpy setup by writer Stuart Beattie (there are many places where I’m sure Mann rewrote the script), propulsive with a clear sense of stakes and incident. They both know that more details just means more things to explain, more things that are not action. With a great pulp work, once you accept the initial crazy of the premise, you get a lot of thrills out of it.

Collateral shows just how personal a genre work can get, something that becomes even clearer if you compare it to a couple of other great genre works of the 00s: Spike Lee’s Inside Man and David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence. (Unsurprisingly, all three are on my personal 10 Best of the Decade list.) The three films take old-school, even clichéd genre plots (Hostage, Heist, Man with a Past) and turn them into unique and darned exciting works; as a fascinating mental exercise, you can imagine the other two directors taking on each film, and how different the result would be–and Lee was apparently offered Collateral. Inside Man plays as the counterthematic work to Collateral: Lee shows how the different races, classes, and ethnicities of New York come together in their own messy way, just as Mann shows the separated individuals and places of Los Angeles.

With Max’s first moment, Mann signals how personally he’ll approach the genre and how much Collateral will play the theme of isolation. (I’m gonna get SPOILERriffic all through this essay.) We begin in a taxi garage; Mann cuts it up into so many disconnected activities: not only are they all active (fixing a car, arguing on a phone), they’re all noisy, a believably chaotic world with Max, the still not-exactly center of it all doing a crossword. When Max shuts himself in his cab, the ambient sound drops out but not the score (that preserves a sense of continuity–if all the sound had suddenly gone out, that’s too much of a jolt), and he takes a moment to check out the cab, clean the windshield, and put up his postcard of the Maldive Islands. What we see throughout the movie is that Max’s sense of his cab as his space is as strong as Vincent’s sense of professionalism. This is the only place he’s truly himself, and he takes a journey of recognition towards that.

With Max’s first moment, Mann signals how personally he’ll approach the genre and how much Collateral will play the theme of isolation. (I’m gonna get SPOILERriffic all through this essay.) We begin in a taxi garage; Mann cuts it up into so many disconnected activities: not only are they all active (fixing a car, arguing on a phone), they’re all noisy, a believably chaotic world with Max, the still not-exactly center of it all doing a crossword. When Max shuts himself in his cab, the ambient sound drops out but not the score (that preserves a sense of continuity–if all the sound had suddenly gone out, that’s too much of a jolt), and he takes a moment to check out the cab, clean the windshield, and put up his postcard of the Maldive Islands. What we see throughout the movie is that Max’s sense of his cab as his space is as strong as Vincent’s sense of professionalism. This is the only place he’s truly himself, and he takes a journey of recognition towards that.

As a cabbie, Max picks up on the fragments of people’s lives, and Mann gives us a neat sequence of them before we get to the action proper. (Collateral’s tight plot allows that; the central story is so involving that the brief thematic digressions never distract us or lower the stakes.) People argue, make deals on the phone, and Max absorbs all of it. Foxx plays Max quietly, so different from his public persona and from the funky, almost goofy style that he brought to Drew Bundini in Mann’s Ali or the cool he would bring to Tubbs in Miami Vice a few years later; there’s no other Foxx character that could believably not give his phone number to Jada Pinkett Smith. The Smith/Foxx scene sets does so much for the film as a whole: it transitions us from day to night, it gives an overview of the space of Los Angeles as a whole, it downshifts the music into R+B tempo (and that’s going to hold with a jazz-oriented version of Bach’s “Air on a G String” in the next scene), and it sets up the repeated motif of isolated people who have a moment of connection. You also see in this scene how much Mann loves actors, and loves watching them, as he just lets the camera observe Smith give a breathtaking eyes-up look at Foxx after she takes the Maldives postcard. You also get some reallllllly heavy foreshadowing here–as beautiful as this moment is, it desperately needs Shane Black and Robert Downey Jr. to stop the film and say “gee, do think this will turn out to be important?”

That observational style isn’t restricted to characters, though, and it continues through the rest of the film; later, tracking through an apartment building, Mann catches little glimpses of isolated lives through windows: a hexagonal fish tank, a rack of dress shirts hanging from the ceiling. Mann has always been such a detail-oriented director, and here he presents a range of details that live up to the cliché “eight million stories in the naked city.” It’s like the café scene in Before Sunrise and the opposite of the “Wise Up” scene in Magnolia: the latter shows us the disconnected lives of the film coming together; Collateral and Before Sunrise imply so many lives on different trajectories.

When Max picks up Vincent, the story kicks in. Like all movie stars, Cruise does his best work when he incorporates his public persona into the character. One and a half of his best performances play off his madman aspect (Magnolia, Tropic Thunder) but Collateral fully expresses his professionalism, and it’s the best thing he’s ever done. Following the rule that a good director makes us see how short Cruise is, Mann and Cruise make Vincent a compact killing machine, someone precise and economical in all his actions. Frank T. J. Mackey and Les Grossman bounced and yelled all over the frame; Vincent never moves more than he has to, almost like a kata even when he’s not fighting. That’s necessary for the plot; hostage dramas almost never work for me because I spend the whole movie (like ZoeZ sez about The Collector) looking for how the protagonist can escape. Here, it’s obvious that Vincent can end your life in less than one second from any position–and we get a moment where that comes true.

More than the professionalism, there’s an anonymity and loneliness to Vincent, something that never quite gets to the level of sympathy but contributes to the mood. There’s nothing really noticeable about this guy, and that’s necessary for what he does; as an exercise (available in the DVD supplements), Mann had Cruise pose as a FedEx delivery guy and drop off a package in a downtown L. A. market. There’s a sense with Vincent that whatever feelings and morals he had, he dropped them a long time ago; he lives up to his self-description as “indifferent.” (This is the film where the Cruise Smile truly looks like Patrick Bateman.) Mann (or maybe Beattie) gives Vincent speeches about the insignificance of life in the universe, and like Heat, it would come across as pretentious if Cruise didn’t so completely and literally embody that in Vincent. (Nearly his first line reinforces the theme of L. A.’s isolation: “whenever I’m here I can’t wait to leave–too sprawled out, disconnected.”) That gets balanced against a real yearning, even if it’s caught only in glimpses: a moment of regret for someone he’s just killed or a genuine bonding with Max, even if he plans to kill him at the end of the evening. Like a lot of Mann characters, Vincent’s professionalism and his emotion are at odds with each other, and that’s also true of the film itself. The way the themes and performances of isolation cross paths with the requirements of genre create the best of Collateral.

That last sentence, of course, well describes Mann’s other great film, Heat. The Los Angeles setting is only the most obvious connection between the two (and Mann deliberately punches that up, with Heat beginning on the Blue Line train and ending at LAX and then reversing that for Collateral); not very far behind that, though, are the conflicting themes of the two films’ characters, between romanticism and professionalism. Heat, so expansive with its action and its cast of characters, could play that conflict out with multiple couples; Eady and McCauley, Justine and Vincent, Charlene and Chris are the first cast, but it’s there right down to Anna and Trejo. That allowed Mann to show different histories, different points in a journey of the couples, different approaches and resolutions. Collateral simply doesn’t have the characters or time (start to finish, the movie takes places in about 14 hours) for all of that, so the romanticism is more subdued and mostly implied. In both cases, the needs of being part of a genre picture–of doing what you have to do–overwhelm any kind of emotional connection, although I’m as curious as anyone to see how Annie and Max’s second date goes.

Law enforcement plays less of a role in Collateral than in Heat, but that plays into the tightness of the plot here and also into the feeling of isolation. The cops in Collateral don’t work together as they do in Heat; Mark Ruffalo’s Fanning is the only one who understands what’s going on and keeps running into a superior (Peter Berg) and an FBI task force, led by the ever-brilliant Bruce McGill, that just won’t listen to him. (McGill gets to deliver a line that’s almost a statement of Collateral’s underlying theme of isolation: “All quiet on the Western Front. Various people are asleep. Various people are not. They come and go in cars, pickups, taxis. Other than that we watch air move.”) Mann has never had much patience with the He Gets Results You Stupid Chief! cop archetype, and he doesn’t let Fanning become that; he’s a smart, controlled guy making a case to his bosses and failing. His final moment, his arm falling like a flag, is a perfect, moving piece of action-movie poetry.

Mann has always explored the techniques of film (The Insider accomplishes the greatest morph in film history) and has always put them in service of the movie as a whole; it’s never about showing off. Here, he uses digital technology in service of the theme of isolation. As we’ve discussed before, perhaps digital’s best aspect is its ability to capture images in low light. (Digital photography, as of 2004, had less resolution than the film of 1995, so Collateral couldn’t have the classical, hard-edged look of Heat.) Since Mann shot this entirely on location, that meant he could capture images of L. A. that hadn’t been seen before on film. At least some of the reason for Collateral was to go back and shoot some of the locations of Heat digitally. In particular, Mann deliberately sought out and captures some of the great backgrounds of Los Angeles. Like all cities, L. A. is a place where extremes of wealth and poverty exist right next to each other; it’s also a place where you might find the most breathtaking city vista in an ordinary alley, and Mann uses exactly that for the site of Vincent’s first kill.

Digital captures the lower light of backgrounds and that means it can capture the distance of backgrounds as film cannot. Many directors have done things to isolate characters in the frame (and so does Mann) but in Collateral, they’re also isolated in the dimension of depth, characters placed in the foreground with a background stretching to a city block or more like an urban version of Lawrence of Arabia. They’re even farther away and lonelier than they would be in a real space, because we expect a sense of distance in the real world, but we haven’t seen a cinema screen extend that far back before.

Digital captures the lower light of backgrounds and that means it can capture the distance of backgrounds as film cannot. Many directors have done things to isolate characters in the frame (and so does Mann) but in Collateral, they’re also isolated in the dimension of depth, characters placed in the foreground with a background stretching to a city block or more like an urban version of Lawrence of Arabia. They’re even farther away and lonelier than they would be in a real space, because we expect a sense of distance in the real world, but we haven’t seen a cinema screen extend that far back before.

We also haven’t seen the L. A. night look this way before, one more benefit of the low light capture of digital. The lights of the city get captured by the haze and smog and reflect back down; it appears here as a warm gray with some orange mixed in, where film could only show it as black. Having lived there, the feeling I always got from it was that of living under a dome. The presence of color, of solidity, and the absence of stars made the city feel like it was trapped, separated from the universe; only traveling east and finding the true night sky felt like escape. Mann’s sense of the uniqueness of the different places of L. A. helps this too. No one part of the city implies the presence of any other part, again, it’s “sprawled out, disconnected.” Mann shoots each location uniquely and doesn’t try and connect it to anything else; this gets reinforced by the structure of the story, a journey through stations of different characters. It’s the right feel for this story, isolated from the rest of a larger story, and these characters, trapped in a world the size of a cab.

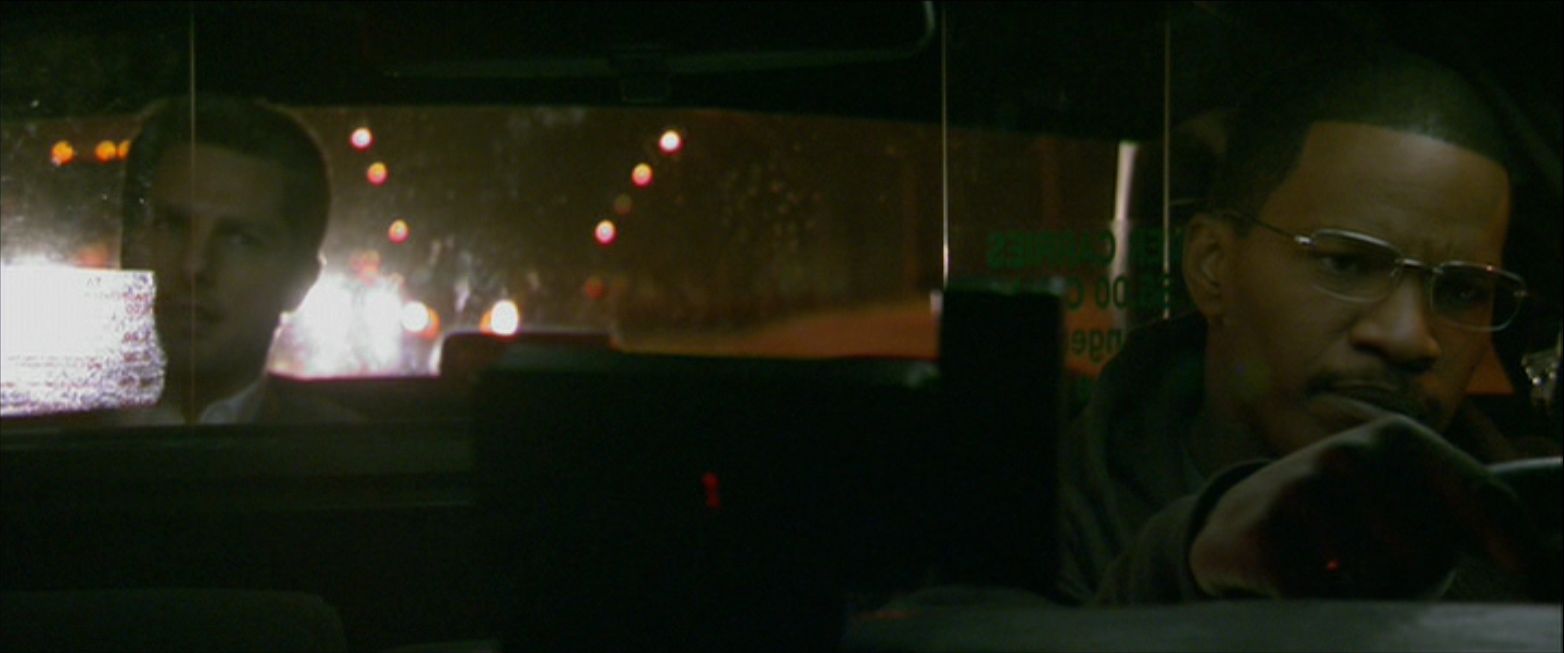

Has anyone ever found so many ways to shoot people in cars as Michael Mann? That skill began at least as far back as Heat, catching McCauley and Eady driving out of L. A. and almost making it, hanging back a little farther than most directors to show them in the frame-in-a-frame of the windshield. Here, where a substantial chunk of the film is just Max and Vincent in the cab, the skill becomes even more necessary and Mann steps up to it. He uses (or creates) a neat architectural detail in the cab itself: a panel that obscures half of Cruise’s face, something he may have picked up from Mary Harron’s direction in American Psycho. Beyond that, he comes at his characters from every horizontal and vertical angle and in combinations of one-shots and two-shots, shooting like a boxer (or like Miles Davis, of whom more shortly), never letting us settle into a visual rhythm or expectation. It’s disorienting, exciting, vertiginous; in some shots, Mann crunches a character into the edge of the frame, pinned with the negative space of the L. A. night sky not just dominating but overwhelming the frame. Here, Max literally looks like he’s about to fall off the edge of the world.

Has anyone ever found so many ways to shoot people in cars as Michael Mann? That skill began at least as far back as Heat, catching McCauley and Eady driving out of L. A. and almost making it, hanging back a little farther than most directors to show them in the frame-in-a-frame of the windshield. Here, where a substantial chunk of the film is just Max and Vincent in the cab, the skill becomes even more necessary and Mann steps up to it. He uses (or creates) a neat architectural detail in the cab itself: a panel that obscures half of Cruise’s face, something he may have picked up from Mary Harron’s direction in American Psycho. Beyond that, he comes at his characters from every horizontal and vertical angle and in combinations of one-shots and two-shots, shooting like a boxer (or like Miles Davis, of whom more shortly), never letting us settle into a visual rhythm or expectation. It’s disorienting, exciting, vertiginous; in some shots, Mann crunches a character into the edge of the frame, pinned with the negative space of the L. A. night sky not just dominating but overwhelming the frame. Here, Max literally looks like he’s about to fall off the edge of the world.

At times, the sense of space and distance becomes an integral part of the action; Mann’s skill as a unified auteur is never clearer than at these moments. In a jazz club on Crenshaw, we’re treated to an edited version of John McLaughlin’s “Spanish Key” from Davis’ Bitches Brew, with Barry Shabaka Henley as Daniel, the club’s owner and lead trumpeter. That spills into a beautiful conversation between him, Vincent, and Max, about his own past, his one, great, isolated moment playing with Miles himself. Like all of Collateral‘s supporting cast, Henley has one scene to imply an entire life, and he does it so movingly; when he said “that. . .season had passed” it’s a regret, but not a dramatic one, a necessary one, letting us know that to go on living means to give things up. Oh, and he also tells the greatest Miles story ever told. (The story is about the necessary isolation of artists, so it fits thematically, but it’s much more about Miles’ status as a supreme and legendary Asshole.) Through sound cues, and through Vincent continually looking around (part of his craft and something he does all through the film), Mann conveys how the club is emptying. And then, he cuts to a single shot of an empty kitchen from Vincent’s POV; it’s beautiful, jarring with its metallic tones against the warm deep reds and browns of the club, and it instantly and precisely transforms the entire scene. Now we know that Daniel is Vincent’s next target.

At times, the sense of space and distance becomes an integral part of the action; Mann’s skill as a unified auteur is never clearer than at these moments. In a jazz club on Crenshaw, we’re treated to an edited version of John McLaughlin’s “Spanish Key” from Davis’ Bitches Brew, with Barry Shabaka Henley as Daniel, the club’s owner and lead trumpeter. That spills into a beautiful conversation between him, Vincent, and Max, about his own past, his one, great, isolated moment playing with Miles himself. Like all of Collateral‘s supporting cast, Henley has one scene to imply an entire life, and he does it so movingly; when he said “that. . .season had passed” it’s a regret, but not a dramatic one, a necessary one, letting us know that to go on living means to give things up. Oh, and he also tells the greatest Miles story ever told. (The story is about the necessary isolation of artists, so it fits thematically, but it’s much more about Miles’ status as a supreme and legendary Asshole.) Through sound cues, and through Vincent continually looking around (part of his craft and something he does all through the film), Mann conveys how the club is emptying. And then, he cuts to a single shot of an empty kitchen from Vincent’s POV; it’s beautiful, jarring with its metallic tones against the warm deep reds and browns of the club, and it instantly and precisely transforms the entire scene. Now we know that Daniel is Vincent’s next target.

Everyone plays at the highest level with what comes next: the slight pushes-in on Cruise and Henley, the beats from Cruise (never taking his eyes off of Henley as he says to Foxx “I’m working here”) and Foxx (leaning back and sighing, conveying “I tried”) and Henley (Mann gives him a held shot on a goddamn regal fuck-you glare), the almost ambient rise of the score, all ramp up the tension unbearably. Mann sticks to closeups and then jumps to a wide shot as Vincent fires the three shots to the head, and then jumps back to a medium shot to watch Vincent catch Daniel’s head before it hits the table. He concludes the scene with another great, moving shot of isolation, Daniel dead at the table, looking like he’s passed out, an unforgettable image of the last resting place of a West Coast jazzman. You wish the guy had a career so that this could be the cover of the box set.

Everyone plays at the highest level with what comes next: the slight pushes-in on Cruise and Henley, the beats from Cruise (never taking his eyes off of Henley as he says to Foxx “I’m working here”) and Foxx (leaning back and sighing, conveying “I tried”) and Henley (Mann gives him a held shot on a goddamn regal fuck-you glare), the almost ambient rise of the score, all ramp up the tension unbearably. Mann sticks to closeups and then jumps to a wide shot as Vincent fires the three shots to the head, and then jumps back to a medium shot to watch Vincent catch Daniel’s head before it hits the table. He concludes the scene with another great, moving shot of isolation, Daniel dead at the table, looking like he’s passed out, an unforgettable image of the last resting place of a West Coast jazzman. You wish the guy had a career so that this could be the cover of the box set.

So many things come together, particularly the theme of isolation, in perhaps Collateral’s best scene, nearly a throwaway moment. It takes place after Max impersonates Vincent to get the information on the final two targets, as Max, Vincent, the FBI, and the cartel’s men are all en route to Club Fever. (What happens at Club Fever is the millennium’s best action scene, and it deserves its own essay.) After a dialogue-free montage of all the different parties driving (cut down from a longer scene where Max drives through LAX to ditch surveillance), the score, heavy with electric guitar, cuts down to a single fading note and we come back to the cab, alone on the road and in the frame. We see, for one of the few times in the film, Max and Vincent in the same shot, and Vincent pauses for a moment and asks “are you gonna call her?” (He saw Annie’s card with her number on it in the scene in the alley.) For a moment, there’s something real here, two men talking, one trying to convince the other to call a woman and just ask her out. That one of the men will most likely kill the other before dawn doesn’t matter; in the moment, Vincent comes across as completely sincere, and so does Max. It’s beautiful because it’s so ordinary, a pause when the rules of genre have looked away for a moment and two men talk. Foxx and Cruise are so good here, both as relaxed as that moment will allow; it’s the most delicate acting I’ve ever seen in an action movie. The brief connection here, visually and emotionally, plays up the distance that the rest of Collateral holds between everyone.

So many things come together, particularly the theme of isolation, in perhaps Collateral’s best scene, nearly a throwaway moment. It takes place after Max impersonates Vincent to get the information on the final two targets, as Max, Vincent, the FBI, and the cartel’s men are all en route to Club Fever. (What happens at Club Fever is the millennium’s best action scene, and it deserves its own essay.) After a dialogue-free montage of all the different parties driving (cut down from a longer scene where Max drives through LAX to ditch surveillance), the score, heavy with electric guitar, cuts down to a single fading note and we come back to the cab, alone on the road and in the frame. We see, for one of the few times in the film, Max and Vincent in the same shot, and Vincent pauses for a moment and asks “are you gonna call her?” (He saw Annie’s card with her number on it in the scene in the alley.) For a moment, there’s something real here, two men talking, one trying to convince the other to call a woman and just ask her out. That one of the men will most likely kill the other before dawn doesn’t matter; in the moment, Vincent comes across as completely sincere, and so does Max. It’s beautiful because it’s so ordinary, a pause when the rules of genre have looked away for a moment and two men talk. Foxx and Cruise are so good here, both as relaxed as that moment will allow; it’s the most delicate acting I’ve ever seen in an action movie. The brief connection here, visually and emotionally, plays up the distance that the rest of Collateral holds between everyone.

In the last half hour, Collateral turns into “pure genre” just as Heat did. (The phrase comes from Nick James’ BFI Modern Classics monograph on Heat, and I recommend it without reservation.) Mann continues to isolate characters in spaces the way only digital can, putting Max on the roof of a parking garage and placing that in the extreme background of Vincent in a building. He’s chasing Annie through her office, and Mann pushes the low-light capture to its most extreme, reducing him to silhouette against the skyline, dropping the sound so all we (and he) can hear is the brush of her crawling across carpet. It’s both incredibly intense and, again, isolating: the loneliness of someone trapped and also the loneliness of the predator. The film has come down to pure genre and Vincent has come down to pure killer.

The final chase through the Blue Line, like all great action films, prioritizes intensity over spectacle, coming down to Vincent, Max, and Annie on the Blue Line train. (No lie: when I first saw the two-level perpendicular intersection of the Blue and Red Line trains in 1996, I said “that’s gonna be in a Michael Mann film one day.”) It’s pure cinema, because from the moment Max fires on Vincent in the office, Vincent can’t see Max and Annie and Mann shoots so we can see that he can’t see them. Vincent keeps chasing them into a smaller and smaller space, pinning them in the last car, and gets off one of the great action-movie lines (“MAX! I DO THIS FOR A LIVING!”) before the final shootout.

The theme of isolation, the performances, Mann’s skill, even James Newton Howard’s music (this cue is the best thing he ever wrote and it somehow feels lonely, too), come together in this last moment. Cruise’s reaction to getting shot is perfect: not the samurai ready to die, but closer to “oh great. A mortal wound. And I had dinner reservations.” Foxx takes off his glasses in what feels like a moment of true respect and connection, and Mann digitally adds a palm tree going by the window as Vincent dies. It calls up the end of Alien³, the moment everyone goes through alone, as Vincent dies and becomes fully anonymous and forgotten, the only witnesses his killer and the target he didn’t get. Mann moves from an intimate shot of him from close and just above to a long shot of him in the train, his colors blending into the background, alone and indistinct, one more body in a city that doesn’t care, an iconic image of urban distance and forgetting, and one that exactly depicts Vincent’s dying words, a bookend to his first lines:

“Hey Max. Guy gets on the MTA here in L.A., dies. . .think anyone will notice?”