To live outside the law, you must be honest.

-Epigraph to Norm Macdonald’s Based on a True Story

“Absolutely Sweet Marie” isn’t my favorite Bob Dylan song. It’s not even my favorite song on this album– I haven’t exactly ranked the songs, but at least two of them would definitely place ahead of it– but that line has always stuck with me as a credo (and not just me, evidently).

I’ve never been one for rules and laws when I have values and principles, and that’s reflected my conduct and choices, personally and professionally, all my life– from a small child to a man of thirty-eight. Sometimes this means I like to play pranks, particularly in a setting I find overly stuffy, a trickster in a world stifled by rules. Sometimes it means getting one over on an institution I don’t respect. Most obviously and importantly, it applied when I was a professional gambler, but even beyond that, it meant going off the beaten path to make a living for most of my life– 2018 is the first year you could really say I went “straight.” But throughout, I always tried to be honest, to myself and to other individuals*.

(* – except when I lie.)

For this essay, though, I want to talk about how that philosophy contributes to my own songwriting, and what I’ve learned from Dylan in this regard.

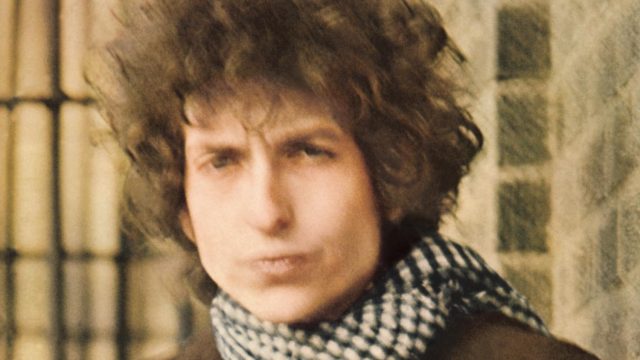

Bob Dylan broke every single rule of what folk music is or was supposed to be. Like most rule-breakers (including me), he pissed off a lot of people with some of those decisions– “Judas!”, etc.– but he was always honest, moving from an honest expression of protest and love of folk into an honest dive into druggy, surrealist rock (and from there would go on to honest dives into country, Christianity, and the blues, among other things), one which reaches its apex with this album.

But it’s a second type of honesty that’s stuck with me here: For all Dylan’s lyrics describe hallucinatory landscapes and their players, they’re always rooted in some truth about what’s going on with him internally, people he knows, or something that happened to him. The most stark example of this in my opinion isn’t on this album; it’s on Highway 61 Revisited‘s “Ballad of a Thin Man,” a song that seems to describe a man stumbling on an inexplicable cast of characters and dialogue, a song written seemingly as stream-of-consciousness rambling nonsense, except that it’s all based on real events and real people. “Mr. Jones” is a reporter trying to ask questions of Dylan and his cohorts, and not really “getting” what they’re about– Dylan has said everything described is based on a real event, and also that the song is “in response to people who ask me questions all the time.”

Dylan writes outside of conventional form but about real events, real people, and real emotional truths. To live outside the law, you must be honest.

Perhaps no better example of this philosophy exists on this record than “Visions of Johanna,” a brilliant song of yearning, one of the best songs ever written and arguably Dylan’s best. At its core, it’s simple: The narrator is with one woman but in love with another. This seems to reflect the reality of Dylan’s feelings about his new wife Sara, fond of her but perhaps still carrying a torch for ex Joan Baez. But it goes from there into a heavily metaphorical seven-and-a-half-minute exploration of those feelings, of observing roads not taken, observing other scenes and people (with an apparent disdain for museums and their goers), and even a self-critical verse about being so self-serious and wrapped up in his feelings and his art, before concluding with a plea for salvation in a crumbling world. (And possibly some references to T.S. Eliot– apt, from my perspective, as “The Waste Land” is one of my favorite things ever written, and I’d arguably consider Eliot and Dylan the two most important English-language poets of the 20th century. You may now commence groaning.)

The dilemma of being with someone who seems right while having your heart elsewhere is expressed perfectly in these four lines:

Louise, she’s all right, she’s just near

She’s delicate and seems like the mirror

But she just makes it all too concise and too clear

That Johanna’s not here

“Visions of Johanna” is the highlight of the album, but it’s brilliant through and through. One of my other favorites is “(Stuck Inside of Mobile with the) Memphis Blues Again”, a rollicking surreal journey full of bent and backwards imagery, that, again, finds itself rooted in reality. “He just smoked my eyelids / And punched my cigarette” refers to Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman, who both ruled his clients with an iron fist and smoked his cigarettes in a bizarre full-fist grip.

I mentioned my own songwriting earlier; I’ve been back into making music in 2019 after long hiatuses and intermittent past attempts at trying. Dylan is my favorite songwriter of all time and I’ve tried to take inspiration from him in this way: Not to compare myself in quality, but to write about real experiences and feelings I’ve had, real people I’ve known, but to twist it just enough to make it uniquely mine, and to make it strange and allusory enough that perhaps other people can find their own meaning in it. (Few if any of you have heard my songs, and I won’t subject you to them unless you really ask.) When I write about the toad and his book, or the lizard and the lion, or the high priestess of the temple, or the rainbow, or “the game;” or I reference No Exit, or the I Ching, or the Church of the SubGenius, or roll up three ideas– one from Leonard Cohen, the New Pornographers, and Neon Genesis Evangelion each– into two lines; I know exactly what it is in my life I’m talking about, whether people or events or feelings. But I want people to be able to find their own meanings in it, too, or, at the least, be intrigued enough to try. (Even if the references are so oblique that the listener might have to dig them out first before even trying to connect what meaning I ascribe in the reference to my own life.)

A few more highlights from Blonde on Blonde:

“Leopard-Skin Pill Box Hat” is a terrific marriage of Dylan’s surrealist instincts and love of the blues and classic songwriting. It’s fundamentally a 12-bar blues song about a man whose woman is cheating on him, but Dylan’s love of finding unique and weird imagery and inverting expectations shines through, no more than in the title object, a peculiarly specific sign of infidelity.

“4th Time Around” is in part seen as a response to the Beatles’ “Norwegian Wood” (John Lennon thought the last line was a warning to him not to crib from Dylan’s style), but it’s also about Dylan’s affair with Edie Sedgwick, a seeming account of her angrily casting him out.

“Just Like a Woman” is a very delicate song by Dylan’s standards, again about an ex-lover, again believed to be Baez or maybe Sedgwick. “Most Likely You Go Your Way and I’ll Go Mine” is, in a typical Dylan contradiction, an upbeat song about a relationship ending– or perhaps Dylan ending his relationship with folk as he moved into rock. “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” seems to be more clearly about that.

And, of course, “Rainy Day Women #12 and 35,” a song that seems to be clearly a thinly veiled allegory marijuana (12 x 35 = 420!) but, as often is the case with Dylan, may be more and less than it appears, as it’s full of Biblical imagery and Vietnam War protest lyrics, and Dylan may have just intended it on those levels. (The latter was often a theme of his early work; the former recurred throughout his life.)

A month after Blonde on Blonde was released, Dylan was in the motorcycle accident that would demarcate a divide in his career, as he began recording the songs with the Band that would eventually become The Basement Tapes, as well as launch into more country-inspired music with albums like John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline. I sometimes wonder if maybe there was something karmic in that– not in the sense that Dylan “deserved” to be in a motorcycle accident, but in the sense that the universe finds a way to rein in rulebreakers once they start going too far. (Dylan did start going back to more traditional forms of songwriting after this, after all.) I had a similar experience at a similar age, one I’ve touched on in previous music articles.

Sometimes Icarus flies too close to the sun. And sometimes you’re just a reckless and foolish young man. But what’s the difference, really?

I didn’t cover every corner of this album, because what can I say about a record that was released in 1966 and has widely been considered one of rock’s all-time greats since? It would be hard to do it justice with anything new, so, as I often do, I tried to make this more personal in lieu of telling you what you already know.

To that end, a fitting coda: As a Bob Dylan fan since I was a young man, far younger than when I met her, my wife and I had our first kiss to “Visions of Johanna.” I knew she was the one for me pretty early on, but perhaps deep down that moment was the first sign; it really seems like the only way it could have happened to me.

The real sign, of course, was that she accepted that I would live outside the law, because she understood that I was honest.