Masochism is underrated.

I should be more precise. Masochism, as it is defined, is a paradoxical, loaded concept. Certainly, pleasure derived from pain exists in a physical, literal sense. I know this because I am a bit of a masochist, in multiple senses of the word; it’s an extension of my interest in exploring the fringes of emotion and sensation. There’s an appeal to finding pleasure in a roundabout way, especially in the possibility of discovering unfamiliar sensations. Because of the fleeting nature of sensation, when our bodies register the contradictory coexistence of pleasure and pain, masochists tend to focus on the pleasurable side to the experience. The mechanics of masochism are borne from objective pain, but subjectively, there is no pain involved. One person’s pain is another person’s pleasure.

I begin Litter Balls with this thought for two reasons. Firstly, it reflects the subject of this regular, indefinite feature: TRASH FILMMAKING. Litter Balls will be both an exploration and a survey – serious with a hint of silly – of cinema’s abyss, carved with low commercial expectations and worse artistic talent. I hope to explore all types of trash: from abject Z-grade curios, to exploitation and its many subgenres, to Hollywood’s forgotten tripe. The only qualifier is obscurity; only rarely do I plan to write about trash classics like Pink Flamingoes, and I’ll tend to avoid sizable cult favourites like The Toxic Avenger. Every film will be categorized by a Type (for instance, “aussiesploitation”), a Flavour (like “tepid”), and a rating:

- Trashy Treasure indicates an unlucky gem in need of proud championing and reappraisal.

- Perverse Pleasure is reserved for terrible movies that nonetheless tickle my fancy, activate my sick sense of appreciation, or simply make for an unconventionally fun time.

- Middling Mediocrity denotes stuff that’s okay.

- Wholly Shit describes the movies that give trash a bad name. Hopefully, I won’t run into too many of these films and defeat the purpose of this feature.

Writing Litter Balls will help satisfy the curiosities I’ve developed about trashy films for the past several years. Coming into this feature with some knowledge but little experience, Litter Balls will be structured like a viewer’s diary, an especially subjective look into the experience of watching the featured film. Watching trash will be a learning process – I’ll be discovering and relaying its histories and cultures along the way. I’m just a newbie, but I believe a unique and constructive edge can be borne from weakness.

The inspiration for my garbage journey can be divided into two interests of mine, developed over the past six or seven years. I’ll start with my marked appreciation for camp, which began when I Youtube’d the quintessential “Oh my god” scene from Troll 2 during my early high school days, on the recommendation of a random magazine article. From there, I ventured into Youtube’s reserves of cheesy clips, Related Links as my only guidance, until I gathered the courage to watch the MST3K episode of Manos: The Hands of Fate, alone. Despite the efforts of Joel and the bots, I was scared back into viewing camp from the comfortable distance of Youtube, with direction from the newly-popular realm of internet comedy reviewers. Then, in January of 2010, I discovered the glory of The Room, following a referral posted on the Battlefield Earth IMDb message boards. I went to those message boards on a whim, but it really was a Leary-esque moment of discovery in my love for shit. I ordered the DVD soon after, and the rest is history. Today, The Room reigns as my favourite bad movie, for both literal and nostalgic reasons, closely followed by Showgirls. Most of my runner-ups, though, I appreciate with varying levels of love; films like Dune, undeniably terrible and yet wholly compelling and exciting, are my go-to.

The second inspiration for Litter Balls comes from my four-year trash flirtation in the form of the videos of Brad Jones, The Cinema Snob. At this point in my life, he deserves a huge shout-out. Not only has he risen as one of the most consistently good internet reviewers in a medium marked by mixed degrees of talent, his best comedic reviews of exploitation films – and especially his first hundred-odd videos – are perhaps the only examples of Great comedy in his medium. Whether or not it’s hyperbole, I feel compelled to shove in as much praise as possible since the influence he has made on my cinephilia is inestimable. Of the examples of how I’ve changed, the most important is the expunging of my snobbishness*. Coming to the realization through his videos that there is worth and entertainment in near every film, trash evolved from scary to gloriously novel. It’s only now, with the catalyst of this recurring feature, that I finally enter into this strange frontier. I hope you’ll come along for the journey.

(I should note that, over 250 episodes strong at the time of writing, Jones’ show will inevitably overlap with this feature. I hope to respect his territory by approaching such films in a way unique to his.)

Libidomania (1979) / Director: Bruno Mattei / Italy

Type: Mondo Film / Sexploitation

Flavour: Feverish

Four paragraphs back, I mentioned that there were two reasons as to why I started this article with a thought on masochism. On a cerebral level, it’s an apt way to introduce how I respond to certain films – but there’s a much more literal purpose, too; I’m starting Litter Balls with a pseudo-documentary about sex perversions.

There are all kinds of fittingnesses here in my choice to make this the first entry. Firstly, it seemed right to start with a movie covered on Jones’s site, albeit on his much-underrated and sadly unfinished roundtable series The Bruno Mattei Show. I also wanted to start right near the bottom of the abyss, to start with one of the most abject, bizarre, unsettlingly non-cinematic films I knew of. At the same time, there is a lot of fun to be had with this film, even if it’s the type of fun engineered for an insomnia-driven 3 AM screening. However, Libidomania can still serve as a throughway to start thinking about how we should gauge trash on a political or social level. Even if it’s a pseudo-documentary about sex perversions.

Any talk about an exploitation film has to start with multiple characterizations. It’s often a way to let people know exactly what they are getting into, useful for such a precarious type of movie. There’s a specificity not only to talks of genre, but also talks of theme and country of origin. When something is called, for instance, Turkish Star Wars, it’s not just to say “Star Wars, but Turkish!”, but it is additionally to indicate the type of rip-off film Turkey has a dubious reputation for. It’s not just any type of Star Wars ripoff; it’s a Turkish Star Wars ripoff.

This prompts me to start with a description about what I got into. Libidomania is a “mondo film”, a sort of travelogue about all that is shocking and debauched around the world. These X-rated Travel Channel films tend to be faked, but they may occasionally slip in authentic stock footage, usually of an ethnographic kind. To further the visceral thrill that these films attempt to achieve, they are presented as collections of relatively narrative-free vignettes. The genre is named after the (pleasingly) Palme d’Or nominated Mondo Cane, a veritable blueprint for all mondo films that came after. Cane would be the only mondo film to get any sort of mainstream acclaim, but its popularity was surpassed by the infamous Faces of Death “real life death” film in 1978. If that movie is any indication, mondo films are maybe about as classy as placing a ketchup packet on the seat of a chair. It’s a good thing, then, that class is irrelevant in this feature.**

In short, Libidomania is a “documentary” about various sex-related topics, most labelled as “perversions” to distance the filmmakers from the material. This harkens back to the classic mode of exploitation, the cautionary film. As long as the exploitation film maintained a mainstream social viewpoint on a textual level, it could subversively cater to what its target audience wanted on a level of subtext. This technique is not exclusive to the B-movie – the most famous example may be Scarface (1932), a studio film – but exploitation tends to take a less subtle approach. In The Trip (1967), an anti-drug disclaimer appears in front of Corman’s otherwise Leary-esque drug film, slapped on by AIP to quell complaints from more offendable types. The effect is jarring, but it ultimately becomes negligible to the target audience. Libidomania, made by people perhaps less shrewd than the ones at AIP, decides to make itself palatable to the masses with an introductory narration accompanied by a montage of sexual bizarrities. First, we get a classy bible quote about the birth of Eve, the beginning of human sexuality. Then, we get a quote from the purely-minded Kraft-Ebbing (whose Psychopathia Sexualis might be seen as proto-exploitation in its dual fetishization/condemnation). Finally, our thesis: “This film will attempt to illustrate sexual aberrations, help us to cure them, and help to understand others that are prey to them.” But, of course, the text is so overpowered by the images onscreen, it violently exits the room and the fetishisizing subtext becomes text by default.

It’s fruitless to list everything you see in this opening sequence. If you’re a sex perversion, you probably make a cameo here. But the sequence is inherently strange, because it’s made from scenes from the rest of the film. The clips here either spoil the money shots (figuratively; my cut of the film is softcore), or try to tease the audience but come off as nonsensical. There’s no fun in seeing a graphic sex-reassignment surgery without any titillating lead-up, but what the heck is the shot of a priest laying under a coffin is teasing at?

What the opening sequence does get at, though, is the visceral experience of sitting through the film. It’s one thing to see someone pour urine all over himself; it’s another to follow that with a man spreading disemboweled guts over a woman’s corpse. Mattei’s film is surreal not within individual scenes (mostly – more on that later); but, once they start rapidly cycling, the experience becomes incredibly bizarre. There’s little structure to the film or its vignettes – something is teased, it pays off, something else is teased, it pays off, and so on. The only calm is in the framing, as a reporter occasionally pops up to interview doctors and sexologists about perversions. Of course, the pacing is very clever. There’s no pretension that the audience will be invested, allowing the movie to work purely in service of the id, giving the audience what it wants with high frequency. It sort of works on that level, since a bunch of the segments are a little gross. The only part that really approaches “shock” territory is the scene of a native bloodletting ceremony, but only because it’s not faked. Otherwise, potential shock is ruined by terrible special effects. One vignette involves a fake penis that looks like clay.

It’s when the thinking, rational human being meets these vignettes that Libidomania achieves something remarkable. The movie is somewhat of an ultimate lucid nightmare – it is unsettlingly impossible to feel in control of the viewing experience when you have no idea what is coming next. I imagine that other, better mondo movies utilize this effect to further ends by actually being disturbing. But what Libidomania can boast – dubiously or not – is that it cashes in on randomness so hard, it becomes absolutely hilarious – while still maintaining the feeling of a waking nightmare. It’s a gallery of demented minds, deformed ideas, and deranged images, all straight from Hell, but it’s also a movie where we see a man and a woman, nude and strapped to bungee cords, try and fail to run towards each other, while another naked man watches delightedly and rubs cream all over himself. The best comparison is the uncut ending of The Devils – a film whose grisliness becomes so heightened as to verge into camp, but still remain grisly. Expand that ending to an 80-minute film, and you get Libidomania. For the extra-adventurous, watching without subtitles greatly reduces coherency, and thus exponentially enhances enjoyability.

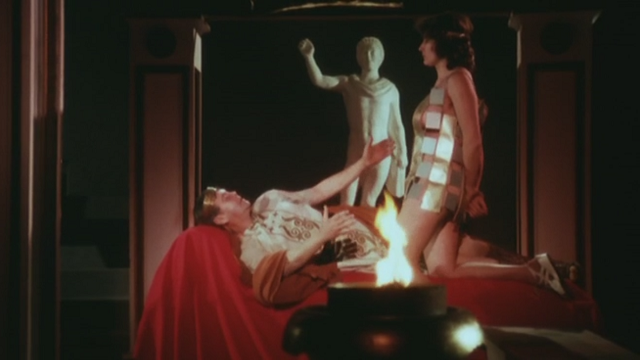

A film composed entirely of vignettes should absolutely not be described with a list, but it’s worth mentioning some of the stranger ones anyway. We see a man fuck a statue. We see a man being treated as a human bathmat. We see what the hosts of The Bruno Mattei Show call “The Sex Olympics”. And my favourite quote:

The scent of incense, the smell of the woman, my priest’s rig, it all comes together to give me an incredible high, like I’m about to explode. And my coffin has a specifically designed contraption for that.

Perhaps the funniest parts of the movie are the ones that have nothing to do with sex. It’s filler, but the kind of filler only a madman would dream up – they stand out due to their sheer unrelatedness. The best is occurs about halfway into the film: we see a woman being chased by attack dogs (with no resolution), followed by an interpretive dance. It simply delights me to be able to tell people that that’s something I’ve seen. At the same time, the out-of-place nature of these segments point to how the film is constructed. Mattei made multiple mondo movies on the uber-cheap, probably relying on the idea that it would be unlikely for anyone to pick up more than one of them (or that anyone would care). For maximum efficiency, many of these scenes are recycled; the Bruno Mattei Show hosts note that the sex olympics footage appears in every single of his mondo movies, for instance. Mattei also sometimes encountered censorship in various markets, forcing him to return to his well of stock footage and find some new padding to appease the censors. It’s easy to imagine that Mattei has a giant safe filled with slices of negatives, in the case that he needs to insert something – anything – into a film.

No matter how much fun I had watching Libidomania, I’m compelled to think about it on a moral level, like I do with all movies. By starting with one of the more extreme examples out there, I’ve made this thought process both easier and harder, as there are no tricky grey areas here. Even though the movie is surprisingly equal-opportunity in terms of gender, many of the actors look visibly humiliated, and some scenes border on emotional violation. Unfortunately, being a film aficionado comes with the baggage of having to accept that some great films are made with the dignity of actors being a minor concern. Is anything in Libidomania more discomfiting than, for instance, Kubrick mentally abusing Shelley Duvall during the filming of The Shining? Or Rosie Perez sobbing during her nude scene in Do the Right Thing? I can’t accuse anyone offended or not offended by a film of being hypocritical; it wouldn’t respect the personal value of a viewer’s response. But what does supporting Libidomania mean, on a moral level? If we think on a literal level, the answer is nothing; no sleazy film producer will see this review and become convinced to degrade people on camera. Neither will a positive review for The Shining. The reason I like both movies is not because people were hurt in their making, and that should be evident to anyone reading it. The seedier scenes in Libidomania are much less entertaining than the rest of the film, and if I recommend the movie it comes with a disclaimer that it’s not an experience for the especially empathetic.

With all that said, I still know it’s not completely right for me to enjoy the movie. It’s a film for those with a little bit of vileness in their brain. And, it’s not completely wrong, either. Exploring the morality of my response will never answer the question “Is it moral or is it immoral?” But the process of thought expands our perception of the world, even if answers are impossible. By defending Libidomania, I’ve placed myself in a moral quandary that will never be resolved, not even with my eventual last entry. I’ll undoubtedly uncover more quandaries as time goes on. That doesn’t mean, though, that thinking about its morality is fruitless. The resolution is not what matters – it’s what I realize along the way. I thus hope to expand my analysis of the morality of trash throughout this series – and continue to raise other important questions, as well. Trash, by being disrespected, will always be evident of the problems glossier films manage to hide; it’s by finding those problems, and exploring them, that we can put the world of trash into better perspective.

(Have any thoughts about morality in film? Write a comment, and let’s discuss!)

Final Rating: Perverse Pleasure

*I still have impossible standards and look down upon other people’s tastes. But at least I now approach every movie with equal peace, love, and hope.

**I should note how humoured I am that Ebert wrote about not just one, but two mondo films.