The United Kingdom has only occasionally been a font for widespread television exportation success. But in the late 2000s, one British television series, a two season drama called Life on Mars, managed to spawn a number of prominent foreign remakes – an identically titled remake in the United States, a version in Spain called La Chica de Ayer (“The Girl from Yesterday”), and a Russian remake named Обратная сторона Луны (“The Dark Side of the Moon”). Taken as a whole, these four series offer an illustration of television adaptation issues in the age of globalism and international media penetration. This examination will focus specifically on a comparison of the two versions that might suggest they have the most in common – the United Kingdom’s original series and the U.S. remake of the same title, and how the U.S. adaptation of the series struggled to refit the premise to an American context and, as such, found success elusive.

By any relevant metric, the BBC series Life on Mars was a success, attracting “over seven million viewers – a large audience for a non-soap, post-watershed drama in the modern multi-channel broadcasting environment” But in the United Kingdom, ratings success has not always meant overseas translation. While there are, of course, exceptions and precedents in broadcast history, the trend towards scripted British television programs being remade for foreign markets is a fairly new and rapidly increasing one. In recent years, British television executives and analysts have noticed the untapped potential in foreign markets. For instance, ITV Studios director of international formats Mike Beale told the press: “We tend to see scripted formats in general travelling well in Central and Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Russia.”

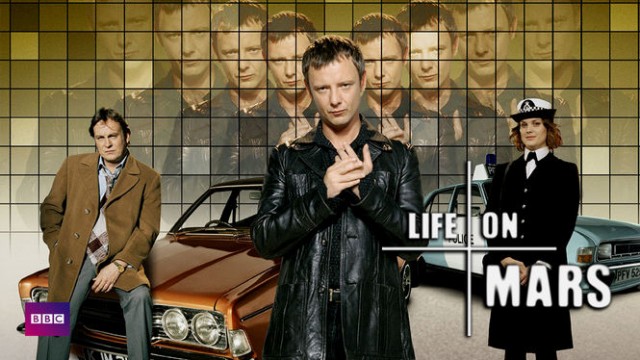

A quick description of the original British series should follow. In 2006, Manchester police detective Sam Tyler is struck by a car and blacks out. When he awakens, he finds himself in Manchester in the year 1973, having apparently just arrived as the new policeman from “out of town.” Sam struggles to adapt to the 1970s-style of policing, with its lax standards on protocol or civil liberties, and its lack of DNA sampling or crime scene forensics. Perhaps more importantly, however, is Sam’s internal struggle: he is unsure whether he has in fact traveled back in time, or if he is merely dreaming/hallucinating the whole affair whilst lying comatose in a hospital bed in 2006, or some other possibility entirety. The program’s title has a double meaning: in a mundane sense, it is the name of the David Bowie song from the 1970s that Sam Tyler was listening to on his iPod as he was hit by a car (when he regains consciousness in 1973, it is playing on a 8-track), but in a more figurative sense it refers to Sam’s feeling that “Whatever’s happened, it’s like I’ve landed on a different planet.”

The series was an immediate popular and critical success with in the United Kingdom, garnering an average audience of 6.8 million viewers during its initial first season run in 2006, as well as garnering an International Emmy Award for Best Drama Series, and nominations from the British Academy Television Awards for Best Drama Series and Best Actor. The program’s success would seem to make it a natural choice for exportation. Overseas sales and broadcast of the program followed quickly, and within a year, the British series would be broadcast in English in the United States, Australia, Ireland, and New Zealand, as well as in both French and English in Canada. Over the next few years, more foreign markets would be added, including Croatia, Hungary, and throughout Scandinavia. But even before those additional broadcast, by 2006, the series was already noted for making “vast amounts of money in oversea sales.” All of this is quite impressive for a show that was very much rooted in British cultural memory of the 1970s, not likely to be shared by people in other cultures.

In keeping with the brevity of average British television shows, even hit ones, the British original of Life on Mars was chosen by its creators to end after only two seasons of eight episodes each, far fewer than the typical number of episodes broadcast of a hit American TV show. The announcement of an American remake for U.S. audiences occurred in 2006, not very long after the first season broadcast of the U.K. Mars. Quickly, at the declaration of a U.S. remake being helmed by veteran American TV producer/writer David E. Kelley, there was a swift and strong outpouring of negative attention directed at the American remake by fans of the original British series. Fans of the U.K. Life on Mars were concerned that the series would lose its essential “British-ness” in translation.

After one unaired pilot episode from David E. Kelley, the American remake finally settled on an almost word-for-word remake of the first British episode to set up the plot of U.S. audiences, this time under a new creative team of Josh Appelbaum, Andre Nemec, and Scott Rosenberg, for the ABC network in the fall of 2008. The basic premise of the story was kept almost essentially intact, just shifted over from one country to another. This time, New York City Police detective Sam Tyler, while listening to David Bowie’s “Life on Mars” in 2008, is struck by a car and finds himself working the same job 35 years earlier in 1973. Each of the five major characters from the U.K. series has an identically-named counterpart in the American version. For the crucial role of Gene Hunt, Sam Tyler’s macho 1970s superior on the detective squad, ABC managed to sign veteran Academy Award-nominated actor Harvey Keitel, in his first ever regular TV series role. This move received attention, and was noted in the American press as a major coup for the network and the show, in addition to Emmy Award winner Michael Imperioli in another supporting role.

What these decisions illustrate is that the ABC network was convinced – or at least, hopeful – of the success of the U.S. version of the Life on Mars format. The executives allowed the series to go through the cost of two separate pilots, and the expense of hiring “name” actors like Keitel and Imperioli for parts on the series. This indicates a willingness to “risk” for the show in order to reap the benefits of great reward when the show is greeted by audiences with enthusiasm and attention. This also stands in contrast with the original British series, which featured a cast of lesser known and obscure actors. The series premiere was given what trade papers called a “sizeable campaign” as well as the benefit of a major platform directly following the hit program Grey’s Anatomy.

Despite great similarities in the initial premise and plots between the two series, divisions and diversion quickly emerged, evidenced not just by plot but also by aesthetic and casting choices. While the original series focused around the dynamic of 21st century post-political correctness, post-sensitivity training police officer Sam Tyler butting heads with his 1970s counterpart Gene Hunt, an unreconstructed and bigoted macho man of the post-war generation, casting choices in the American remake complicated, if not diluted the relationship and its impact on audiences. As played by British actor John Simm, the character of Sam Tyler can be accurately described as a kind of everyman figure. He is of average height and build, and is skilled in detective work, but lacks any flare with a gun (unlike most American cop show heroes), nor is he dashing in a car chase.

On the other hand, the American incarnation of Sam Tyler is much taller, and is in notably athletic shape, emphasized by a number of shirtless scenes by Irish actor Jason O’Mara, who adopts an American accent to play the New York Sam Tyler. This version of Tyler is skilled in a gunfight and in one scene is able to survive several gunshot wounds with nary more than some slight discomfort. In one episode, a character, sizing up Tyler, comments that he looks more “like an astronaut” than a cop. All of this together indicates that while the British version of Tyler was formulated as a relatable and commonplace everyman figure representing the average Briton of 2006-7, the Americanized Tyler is instead an aspirational figure – his above average physique, glamorized physical skills, and the connections drawn between him and the rare and literally “above our heads” occupation of an astronaut, all combine to make this version of Sam Tyler a figure that loses the one-to-one connection between audience and protagonist that exists in the British original, where Tyler is present in literally every scene.

Similarly, the casting and interpretation of Gene Hunt as played by Harvey Keitel serve to turn Hunt into a very different character. The actor who played Hunt in the British original was Philip Glenister; his imposing stature and burly frame make Tyler seem quite small in comparison, and though he outranks him and appears to be slightly older than Tyler (Glenister was born in 1963 while actor John Simm was born in 1970), they are essentially peers. On the other hand, Harvey Keitel (born in 1939) was 69 years old during the filming of the American Life on Mars, and far shorter and slighter than Jason O’Mara’s Sam. The combination of size and age – though an inherent and inexorable part of casting big-name actor Harvey Keitel in the series – serve to render the sensitive man/macho man dynamic of Tyler and Hunt much less effective, or, at the very least, muddled.

In some instances, however, it is the similarities that are more galling than the differences. For example, the title of the series indicates a lack of adaptability between the United Kingdom and the United States. In the original British program, the titular song, David Bowie’s “Life on Mars?” serves as a kind of atmospheric bridge between the 21st century and the 1970s. This is fitting, as the song was a significant pop cultural hit in the United Kingdom during the year the show is set, 1973. During the summer of 1973, Bowie’s single release of the song went all the way to the #3 position on the official U.K. singles charts. By contrast, in the United States, the single was never even released. The decision to keep the song as an important part of the plotline in the American version, and to retain it as a title despite its presumed lack of recognition to American audiences, suggests two things. The first is that the producers behind the American remake of Life on Mars were intent on capturing certain external signifiers of the British Life on Mars’s success, and the second, following from the first, is that the same producers were sufficiently unperturbed by the cultural differences between the United States and the United Kingdom as to potentially sacrifice recognition and cultural nostalgia in an attempt to imitate the original British program’s popular success.

But certain fundamental changes in the adaptation derived from clear cultural context. Even before the American remake officially aired, producers and writers for the show publically announced that they were significantly revising the original’s show mythology and mystery elements. Calling the original British program’s narrative of a man doubting his own sanity, and the audience doubting whether what was happening to him was real or merely a dream “unsatisfying,” American executive producer Josh Appelbaum decided to change the series’s plotline to a “mystery.” The decision is one that might seem somewhat inexplicable. After all, the original series was an enormous hit in Britain, so what evidence was there that the “dream” plotline was unsatisfying to audiences? But the roots of this change lie deeper in the storytelling frameworks that have proved alternatively successful or unsuccessful in each country.

In British dramatic television, a popular desire towards mentally challenging fare dates at least back to the seminal series of the late 1960s, The Prisoner. In the ‘60s, the show was notable for its “combined realism, surrealism, and a theatrical artificiality [. . .] its formal experimentation [that] further disrupted conventional modes of viewing.” Importantly, it managed to bridge the perceived gap in British television between popular entertainment for mass audiences and “serious” programming that would provoke or challenge viewers. Like Life on Mars, this series confounded viewers with its ambiguity about what was “real” and what was not; about who was in “control” and who wasn’t. In the decades to follow, British television saw similar successes that were challenging in their mergers of traditionally “safe” genres (like, say, the cop show) and more experimental formats or elements. Hit series like 1985’s Edge of Darkness were noted for their daring combinations of genres, and incorporations of “unconscious desires [. . .] [that] merge personal loss with an entire ecosystem come to grief.” So while there existed a cultural context and a decades-long tradition in the United Kingdom for pseudo-existentialist dramas merging the “real” and the “unreal,” the United States has much less of a history in that area.

The American version of Life on Mars did not come close to reaching the same levels of popular, commercial, or critical success that its British counterpart did. While the premiere episode attracted high viewership numbers in October of 2008, ratings quickly declined at an increasingly rapid pace. By the end of its first season run, the U.S. Life on Mars was drawing fewer than five million viewers per episode, far below the U.K. program’s average audience of 6.8 million (which importantly comes from a country with a much smaller population than the United States, and thus makes up a larger percentage of overall television viewers.) By March of 2009, the series was canceled by ABC, which gave the Life on Mars producers a chance to wrap the show up with a total of 17 episodes.

Similarly, the critical success of the remake and its pop cultural impact was considerably less than its British ancestor. While the original British series attracted major awards like an International Emmy for Best Drama Series and multiple nominations at the British Academy Television Awards, the U.S. remake earned only a single comparatively minor technical nomination at the Primetime Emmy Awards. The zeitgeist impact of the remake was also minor in comparison to the British series. The British series spawned multiple tie-in books, written from the perspective of characters on the show. Beyond even its second and final season, the British incarnation of Life on Mars continued its mythology and story in the spin-off series Ashes to Ashes, which was also a hit and ran even longer than the original series, while continuing on with its plots and overarching questions.

So by almost any conceivable metric the United States remake of international success Life on Mars was a failure. The reasons for this lie in the failure to properly integrate and reconcile the reasons for the British program’s success with an American cultural understanding. In addition to the aforementioned diluting of the character dynamic between Sam Tyler and Gene Hunt (a consequence of attracting big name actor Harvey Keitel), the loss of the premise’s inherent ambiguity and semi-surreal qualities, and the failure to “translate” the cultural meaning of David Bowie in Britain as opposed to the U.S., the American remake of Life on Mars failed to make a truly American appeal to its viewers, rather providing incomplete and inconsistent imitations of the British format. Commentators and analysts have noted the that “the sociocultural patterns reflected in the US version are only weakly, being reduced to mere photographic representation of New York City in the 1970s.” In other words, the BBC telling of the story was rooted and derived from very clear and deeply felt ideas about nostalgia, time, and the difference between Britain in the 1970s and Britain in the 2000s, but the ABC retelling was unable to find and develop an organic reason for its existence beyond the fact that the British series was a worldwide hit, and thus, was unable to strike the same chord with its audience that the BBC original was able to strike with British audiences.

By contrast, more success in remaking could have been found by changing more of the premise. As mentioned above, there followed in 2012, a Russian television adaptation of the Life on Mars story, this time called Dark Side of the Moon, after the best-selling Pink Floyd album by the same name. The name was not the only aspect of the series that was altered; the year that the protagonist traveled back to was changed to 1979, and the essential character dynamic was totally changed to fit cultural settings. The political contrast between 1979’s Russia and 2012’s Russia was such that the central character – this time named “Mikhail” – was no longer a regulations-following 21st century man among the more macho and loose cannon policemen of the 1970s – instead, the cultural memory in Russia of the Soviet municipal police is that they were very subdued and “buttoned-up” in comparison to cops of 21st century Russia. As a consequence of this, Mikhail is now a “corner-cutter” while the Gene Hunt counterpart is a “straight-laced stickler for the rules.” The title change also is indicative of the greater transformation of the show to fit Russian expectations, as David Bowie’s song “Life on Mars” was not a hit and is not well-remembered in Russia, whereas the Pink Floyd song and album which give the Russian show its title were well-remembered. Perhaps as a result of these cultural adaptations, The Dark Side of the Moon was a “huge hit” and was the most-watched TV program in its timeslot when it aired in Russia. That is to say, this Russian version was able to change so much of what made the British version of Life on Mars a success and still be a success itself because the creators of this program understand that the success came not through superficial external details, but through the cultural chord being struck by the nostalgic plot and mythology.

The conclusion to be drawn from these findings is this: even in the era of globalism and transnationalism, the successful of a piece of entertainment will still be in some ways limited by the cultural expectations of a national audience. As in the case of the multiple versions of Life on Mars, if an international adaptation/translation takes on the external formats of an original without translating the feeling or the effect of what the original show meant to national audiences, it cannot expect to find the same kind of success. Even in the United States and Britain, two cultures with a shared cultural heritage, a great deal in common, and a kindred language, much can be “lost” in translation. The example of Life on Mars is, to a large extent, an illustration of the limits of globalism when it relates to pop culture.