With its simultaneous impressions of abundance and incompletion—its profusion of abandoned and regenerated stories, stories that haunt one another, that have a life beyond the frame, that invite us to complete them—Mysterious Object at Noon is as close as Apichatpong has come to a statement of intent. His work is often described in terms of its mystifications, but as this humble yet capacious film reminds us, Apichatpong’s vision is a fundamentally generous one, and his magnanimity extends above all to the viewer.

-Dennis Lim, “Mysterious Object at Noon: Stories That Haunt One Another”

One of those unavoidable paradoxes we face in criticism of the high v. low genres of popular culture is that the attempts we use to break down these distinctions often reinforce them. When we say things like, “It’s a superhero movie, but a good one,” or “It’s an art film, but you’ll enjoy it,” we’re trying to lure audiences from one end of that divide to the other while simultaneously accepting and even strengthening the very fact of that divide: superhero films are trash. Art films are boring. The exceptions only prove the rule.

It’s hard for us Westerners to break out of habits that go back to the late Renaissance. They themselves weren’t responsible for creating a gap between elite and popular culture – heck, that’s existed as long as an elite has existed – but people like André Félibien, who designed an official “hierarchy of arts” for French academic criticism in the 1660s, did do a lot to reify it, to apply the rationalist (and moralist!) penchant for categorization to areas like poetry, theater, music, and art. Later generations might rebel against the specifics, but they often ended by merely switching out their preferred genres without damaging the existence of a hierarchy, or the assumptions undergirding it. Though we obviously don’t have space to detail all the ways this idea has morphed over the last four hundred years, suffice to say the existence of a hierarchy in itself has turned out to be an awfully durable idea. This film is “not made for the critics.” That film is “for people who like character development more than explosions.” Superficially rejected, it’s nevertheless all over The Discourse, even for a medium that was originally supposed to be for and of the people.

Today, when we divide culture into “high” and “low,” do we mean some inherent quality of the work itself, or the intentions of the artist, or the assumed audience, or the actual reception by the audience? And for each of these options, what then do we do with something like Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Mysterious Object at Noon, which opened in the United States in 2001 to a mix of critical praise and bafflement? From the outside, the movie’s résumé is chock-full of the conventional bona fides of high culture: a director who graduated from the prestigious Art Institute of Chicago and who spends time between films designing museum installations, a film constructed around a formal device drawn from the 20th-century French avant garde, a merging of vérité filmmaking and fictional reenactment in grainy black-and-white: in other words, the kind of film that a certain critic I won’t dignify with a link has derisively dismissed as ready-made for the festival circuit. Within Thailand, however, the film was collaboratively-constructed by children, workers, senior citizens, and traveling performers across the countryside, allowing them to indulge in the caprices of their own imagination, which largely involved reproductions of “low” cultural artifacts like TV soap opera, folk tale, and pulp fiction; the director himself described it as “rather old-fashioned”; and if Benedict Anderson’s anecdotal evidence is representative, Apichatpong’s films are largely ignored by big-city Bangkok theaters and intellectuals but regularly rented out and enjoyed by home viewers in the same rural landscape in which Mysterious Object was filmed, i.e., about as far as one could possibly get from the pretensions of the international festival circuit. So what do we do with all this?

Of course, we don’t have to do anything with this at all, but it’s the kind of the example that sticks in the back of my mind when we debate genre, high and low culture, and audience expectations: what we know, and what we think we know, is frequently insufficient and limited to our very specific time and place. As Jonathan Rosenbaum put it in his very positive review, “how many of our ideas about experimental filmmaking are predicated on unthinking Western reflexes and traditions that exclude many small countries as a matter of course?” (Note how Rosenbaum reinforces the tendency he challenges, though.) The hierarchy may be durable within the West because our own artistic works are products of that system, regardless of the degree to which they challenge it. Operating on what appear to be a different set of assumptions altogether, Apichatpong’s movies seem to casually blow right through ours.

Or maybe I’m just riffing here, but here’s what I can say for certain: I love this movie, and like all of Apichatpong’s films, it brings me a great deal of relaxed pleasure, or pleasurable relaxation. It is, like all of his movies, deliberately paced, funny, meandering, warm, confounding, and unlike anything else out there.

Briefly: the originating idea of Mysterious Object is the exquisite corpse, an artistic technique developed by Surrealists around World War I, but based on much older and less formally codified games that anyone who’s sat around a campfire and finished one another’s stories knows how to play. One person starts a tale, another continues it, another continues it further, and so forth.

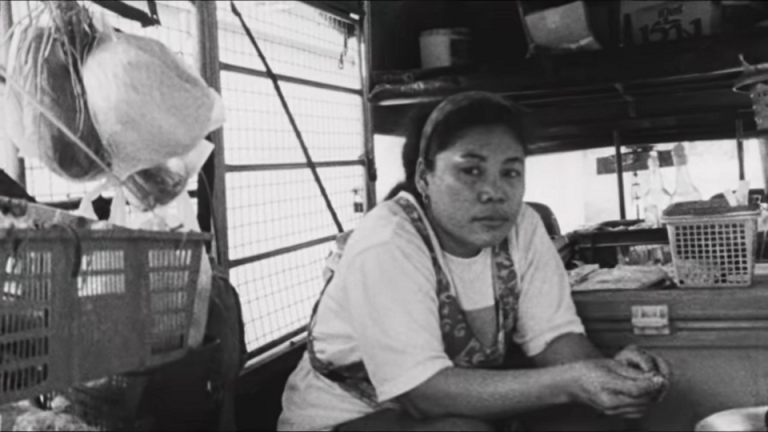

Traveling north to south across rural Thailand and allowing passersby to participate, Apichatpong introduces two novelties: first, after obtaining documentary footage of the storytelling itself, the production team reconstructs the story with actors on a set, and these two parts are edited together, such that we “watch” the story as it’s being improvised by its tellers. (Films that mix actors and non-professionals are nothing new; films that cede creative control to the latter are few and far between.) Second, Apichatpong respects the game’s tendency toward chaos and does not interfere. If you’ve ever played this game before, you know that it tends to dissolve into nonsense much more often than it yields anything coherent: in Mysterious Object, the already wobbly story — a schoolteacher, a student, a mysterious ball that turns into a boy, maybe an extraterrestrial, a duplicate teacher, and so on — falls apart entirely in the hands of schoolchildren, who bombard it with increasingly absurd, unfilmable, contradictory contributions. Oh, well!

It’s not about the story, anyway — or rather, the story is just a device, and the time spent getting to know these people, and ultimately lazing about on a hot afternoon, are where the movie’s true pleasures lie. That’s not to say that all the digressions are pleasurable in content (some of the interviewees are frank about hardship, personal and national), but that sum effect of these stories is the kind of warmly human tapestry that feels unforced in a way that more purely sociological films are not: the key difference is that this film encourages its objects to be subjects, that is, they are co-creators, and their pleasure at the act of creation is what gives the film its unique energy. Because that energy is more important than the product, it’s no big concern when the more formal requirements of story are abandoned. Like most of his films (Tropical Malady excepted), Apichatpong lets the final reel fade out into non-narrative reverie, the camera capturing people in unmotivated play, or relaxation, or casual communal activity. Who cares about high-low culture debates, or other needless abstractions? Here is a soccer game, a warm river, a child with a dog.

And then, the camera broke.