At 2:23 p.m. Central Time, on July 25, 2005, The AV Club became fully aware of its readers. The website of The Onion‘s arts section relaunched with a new design and a few new features — a message board where readers could talk pop culture and a blog that, unlike the site’s reviews and features, allowed comments. The first comment on editor Keith Phipps’ first blog was positive! Others there and in the forum were less so, along the lines of “The redesign however is bad. The colors look like baby poop, blogs has [sic] the scum of the internet. Everybody and their grandmother has one, why do we have to have one on a site such as this? What is happening here?”

A few days later, movie critic Scott Tobias weighed in with a comment of his own. While he said the new site “has allowed us the flexibility to add more content and try new things,” he understood why long-time readers might be upset about The AV Club‘s new layout: “When you’re used to seeing something in a certain way, it isn’t always pleasant to have things tossed around. (It’s like coming home and finding someone’s moved your furniture.)” That tossed-off parenthetical suggests a few things. The first is that visitors to the site aren’t wrong to feel they have a claim on it — “your” furniture is being moved. And that is part of a larger concept, the website as a place. A digital manifestation of a physical location, where people come and go but some stability remains. Where people want to go, because of the place itself.

***

The forum, as a place where people know they can gather to talk about matters small and large, dates back to pre-Christian Rome. In what seems like an equally ancient time, the internet of the 80s and early 90s, forums flourished as well (and of course they’re still around today). They were well-established types of internet communities, so it wasn’t surprising that The AV Club developed one that saw a decent amount of use. But the forum kept discussion isolated, away from the interviews and movie and music reviews that offered plenty of things to talk about. A forum is an open place where anyone can try to start a conversation, it doesn’t really have an identity of its own, and The AV Club‘s forum was soon eclipsed by the discussions that took place in the blog comments.

The AV Club of 2005 was well into the second generation of an institution that was created more than a decade earlier. The founder, Stephen Thompson, had left, but most of the writers had been working there for years and had honed the site’s voice into a wiseass authority, sincere in its likes and withering in its dislikes and greatly skeptical of the entertainment world it was ostensibly a part of. A classic 2000-era gag created The AV Club For Men, an issue parodying lad mags, where one interview consisted of asking Steve Albini questions directly out of Maxim, and every year would end not only with best-of lists, but a Cheap Toy Roundup of half-assed gewgaws and a countdown to the coveted Least Essential Album. The site riffed on Films that Time Forgot and Commentary Tracks of the Damned, but also boosted art and artists that were outside the mainstream conversation – the people who had, to use the title of a book of interviews from the AV Club’s first ten years, the tenacity of the cockroach.

This felt different from other entertainment writing coming from either coast, a sensibility that welcomed other writers but was born and located in the Midwest and the Chicago home of the site and of The Onion. The pop culture discussed here was real, as opposed to the fake news of the main publication, but the same kind of humor ran through both sites. Forums and bulletin boards had helped define the web through the mid-90s but greater ability to build websites and greater access to them changed the dynamic. Now a person or a group of people could create a place with its own specific attitude, one where people of a similar bent would want to hang out. If a forum is similar to a park, an open space where lots of people can hang out and gravitate to various areas, these places were more like bars. In a review of Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets — a 2020 film about the last day of a dingy dive — longtime AV Club freelancer Vikram Murthi talked about the transient allure of the bar:

“In the popular imagination, a bar is a space defined by contradictions. It’s a social setting that fosters community, but it’s a community built upon casual connections, transactional relationships, and a readily available drug. It’s a haven for many, a place of refuge from the outside world. Yet, the safety it provides is temporary, and neither the alcohol nor the kept company can protect anyone from themselves. In a bar, everybody might know your name, like the song says. But a bar also cultivates a certain anonymity. Identities are disclosed, but their full picture may never come into focus.”

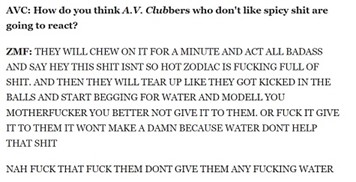

The AV Club didn’t give its readers booze, unfortunately, and it did not exist to provide a service the way a bar does — its writers and editors were creating work of their own. But with those blog comment sections, the site quickly developed that atmosphere Murthi describes. Readers were more connected to the work and the writers would regularly join in. There were alliances, fights, angry walk-outs, discussions that became arguments, arguments that became discussions. People entered into that liminal space of quasi-public interaction — commenters used pseudonyms (although a few brave souls put their real names out there) but had consistent personalities, barring the occasional sock puppet. You knew who you were talking to even if you didn’t know who they were.

It wasn’t too long before the rest of the site’s articles got comments and discussions of their own, and in 2006 the site went from weekly updates to daily ones, complete with a Newswire collecting and commenting on the latest developments in pop culture. (Like all news of the day, this becomes fascinating commentary from the past, like the October 2006 headline “Weekend Box Office: Scorsese Triumphs Over Rank Stupidity. For Now” or the wonderful January 2007 lede “Blogs are ablaze with rumors of a Van Halen-David Lee Roth reunion tour…”). And at the beginning of 2007, longtime staffer Nathan Rabin started a project called My Year Of Flops, where he would immerse himself in a “riveting world of failure, hubris and colossal miscalculation” as he reviewed some of the biggest movie disasters of the last 50 years. I’d been visiting The AV Club for a while at this point but the prospect of talking about bad movies, a longtime interest of mine, was too enticing to just read. I borrowed a name from one of my favorite films and dived in.

MYOF, as it came to be called, was really where the site became a larger presence in the online world. In the very first entry, for Elizabethtown, Rabin coined the term “manic pixie dream girl,” which has haunted the internet ever since, and by the end of the Year of Flops the AV Club was pulling in a million unique users, according to The Onion‘s owners. But more importantly, it distilled the mission of the site remarkably well. It crapped on the deserving (Batman and Robin), supported the misunderstood (Ishtar, Freddy Got Fingered) and marveled at the weird (The Apple). And it gave readers a chance to support or condemn those judgments. Or to just claim first comment, or demand Rabin cover a certain movie next, or make weird in-jokes about Frank Darabont’s original drafts for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

The AV Club kept current with whatever was coming out at the time but was not beholden to release schedules and teases from the drivers of pop culture. Newswire re-reported the same entertainment news as everyone else but with irreverence and edge, understanding that when all of the news is the same, it’s the margins where you find things of value and the doodles in the margins are what kept people coming back. A lot of The AV Club’s best features during this time looked to the past, and the dustier corners of the past at that. After Rabin enveloped himself in flops, longtime freelancer Noel Murray spent a year forgoing new music and just winnowing his own vast library of downloads in the feature Popless, finding connections between artists and musing on how he found them in the first place as he decided whether to keep them around. Tasha Robinson dug into the similarities and differences of adaptations in Book vs. Film, which sometimes was and sometimes was not pegged to a new release. Tobias developed the New Cult Canon, incisive appreciations of movies that had developed fervent followings in the past 30 years. In Box of Paperbacks Book Club, Phipps dug into a crate of cheap mid-century genre fiction he got for a song, panning for gold in pages of pulp and occasionally finding it.

Some of these were more popular than others but they all found an audience that could recognize and appreciate the thoughtfulness and skill behind them as well as the snarky features. And that audience became an increasing presence on the site. A few people crossed over from the comments to actually writing articles, and articles themselves drew from the community under them. Staff took suggestions for food to inflict on unsuspecting fellow workers in Taste Tests and searched for the sources of readers’ half-forgotten pop culture memories (these were almost always either Ray Bradbury stories or parts of a bizarre anime called Unico). And as the site started to cover television in the now-ubiquitous recap form, it began to see more and more of what were ironically called “reasonable discussions.”

Have you ever tried to listen to every conversation at a busy bar? There is a lot going on — sincere discussions, goofing on in-jokes, blatant horniness. Wild stories and dirty jokes. Yelling about what’s happening on the TV this very minute, and grievances and takes that have been kicked over for years. Some articles, particularly Newswires, were essentially subject prompts for people to riff on and commenters created gimmick accounts with their own rules and dynamics. Commenters colonized an entire feature, the Spy-ish Tolerability Index, and turned it into a free-for-all of life updates and whatever else was on their minds (same for an absolutely insane, 100,000+ comments section for the Season 4 finale of Community). Maybe this wasn’t too different from other web communities, but it had its own spirit.

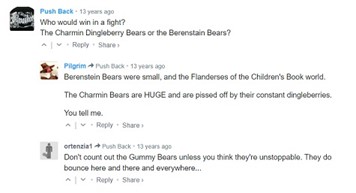

There were millions of ephemeral conversations, and things that still make me laugh today. A passionate discussion of the worst TV show ever made, building off the initial assertion that it was Mama’s Family, not Under One Roof. The increasingly unhinged parodic outrage at David Sims’ Seinfeld reviews. Prompted by the beloved Year in Band Names feature, a commenter suggested the moniker “Don’t Tell Mom The Babysitter’s Dad” and that “band” has lived in my brain ever since — right next to the sweet Laurel Canyon sound of Dawes, of course. And in the middle of this was weirder material, like an article about Choose Your Own Adventure books leading someone in the comments to write a CYOA about whether or not to get high that day that was funny, melancholy and oddly beautiful.

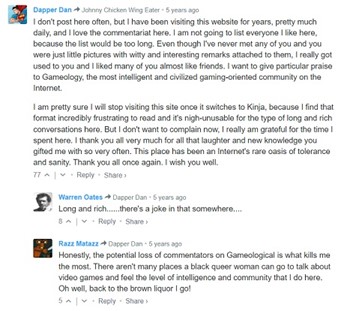

And if the commenters took their humor cues from the site’s house style, they were similarly serious about likes and dislikes. People would back up or attack reviews, but also throw their own recommendations into the mix — I blind bought a copy of Clean, Shaven because someone who seemed to know what he was talking about recommended it and wound up blown away by an intense, unsettling movie I’d never have heard of otherwise. And I pushed my own favorites (watch Matinee, people!), because it was more likely than not someone was listening, interested just like I was in hearing about something worth our time, or at least about something we could all laugh at. Commenters came and went, some got married to each other and some were revealed to be elaborate hoaxes, entire groups of commenters created their own spin-off sites. But a surprising amount of people who came to this place stuck around for years at a time, passing around stories and in-jokes and recommendations.

***

One thing that is consistent across all internet communities is the belief within the community itself that it is better than those other yahoos commenting in other places — smarter, funnier, more erudite, less unhinged. And another thing that is consistent across all internet communities is that they’re all wrong to some degree about this. The AV Club comments were filled with insightful essays and hilarious jokes; they were also filled with “ironic” racial humor and a ton of non-ironic sexism, with many commenters treating any female interview subject as an object. The site cracked down on this occasionally and even nuked a few comment sections from orbit, but the attitude stayed for a long time. And some readers harassed female writers of the site, going from extremely shitty comments to outright stalking and threats – this apparently continued for a long time. Anonymity in a public space can let a person relax — I’m certain The AV Club‘s traffic increased in part because commenters were goofing off at work, secure that a zinger about the Starz network made during office hours wouldn’t be traced back to them — but it’s also cover for people to be huge assholes. The commentariat had a lot of personal sharing, which can be a wonderful thing until it’s used against you, and I believe a fair amount of people held back on who they were not because they wanted to, but because they didn’t want to be harassed.

The writers and editors pushed back on this and worked to make the site a welcoming and inclusive place. But The AV Club still had blind spots. Writers of the mid-to-late aughts were overwhelmingly white and largely male; the balance of the latter improved but the former stayed consistent for quite a while and that isn’t a reflection of who was making — and consuming — the pop culture the site was covering. It’s unfortunate, a reminder that a place needs to bring in everyone if it wants to be for everyone.

But for a while The AV Club managed to grow into a wider audience while staying true to what made it worth going to in the first place. It brought in bands to play cover songs in their office and started its own music festival, and it expanded TV coverage into “Classic” programs like the X-Files and Newsradio and the site’s long-beloved Mr. Show, treating older works as worthy of the same kind of analysis that “Peak TV” was getting. It broadened its focus while keeping its soul, expanding coverage to videogames and even sports. And it survived a major exodus of the writers and editors who had built the site over the previous decade — Phipps suddenly left at the end of 2012 and a few months later Rabin, Robinson, Tobias and writer/editor Genevieve Koski joined him in starting The Dissolve, a movie-focused site run through Pitchfork that most of us here are somewhat familiar with. One way you can measure the power of a place is by how it can survive change while still remaining itself, how its community doesn’t replace individuals but creates continuity between them. New writers may have been hazed a bit, but were ultimately welcomed aboard. The site lost some of its strongest voices, but those people had brought up writers who clearly shared similar values and what they meant to the place they were now in charge of.

***

They would not be in charge for much longer, and apparently the pressure to change what made the site great was already well underway, per Phipps: “We were told to emphasize lots of bite-sized content because…that and sponsored content were the future of the Internet circa 2012.” But that got worse when Univision bought The Onion in 2016, putting it under the same umbrella as former Gawker Media sites like Deadspin and Gizmodo. Fine places with their own styles, now being clumped together as content creators — a food court instead of a bunch of bars. The tone of the site shifted to more trend-chasing and viral-piggybacking Great Job, Internet! blurbs; slideshows and videos became more prevalent. And in 2017, the dreaded switchover finally occurred — The AV Club moved to the Kinja platform used by the rest of the Univision sites and widely despised by all commenters there (although, as some staffers pointed out, as a CMS Kinja was a significant step up from whatever The AV Club had been using for the past several years).

As expected, Kinja devastated the commenting community. It was glitchy and actively discouraged conversation by design, requiring people to click every time they wanted to load more than three comment threads at a time. The site’s editors actually worked to port over more than a decade of comments, which they surely didn’t have to, but even then a ton of material was lost. The site had gone through multiple redesigns over the past decade and commenters had hated every single one, with the shift from full anonymity to needing to register a name (or at least a pseudonym) being a particular point of contention. And then they got used to the new system. This was different, and the last comment thread before the shift was full of people mourning a place they had helped make and could be themselves in. (It was also full of bad puns and in-jokes, of course.)

But what was worse was what the new platform did to the site itself. The site’s design was truly awful and utterly unreadable in the mobile version, and if you did click an article you’d be rewarded with autoplaying video and constantly re-loading and shifting text. Back during that first redesign in 2005, Phipps goofed on what readers could expect: “Coming soon: Bad flash animation, MIDI songs you can’t turn off, pop-up porn ads, graphics that take forever to load, green text on black backgrounds, and did I hear someone say they’re dying for a chance to ’win’ a ’free’ ’iPod’ if they can shoot an animated duck?” It took a decade, but Kinja turned the clock back to the worst the internet had to offer and turned that joke into horrible reality.

The shift in the site’s values mirrored the shift in design. For a while, it had been clear the traffic-chasing crap was part of a strategy that still let writers get away with good work — the clicks paid the bills so the site could still host less popular but more vital writing. In the way that Univision tried to have all of its culture sites spew out of the same faucet, The AV Club as presented by Kinja placed the dross on the same level as actual features and criticism, bumping pieces that clearly had taken time and effort to produce down the page for the latest teaser video or promotional photo release. The site was now a slurry of content, and the implication was that people reading should open wide and chug it down instead of talk about just how shitty everything was getting.

And things could always get shittier. Private equity assholes Great Hill Partners bought Univision’s sites in 2019, rebranded everything as G/O Media, and continued to push uncritical coverage of popular things, the antithesis of the AV Club‘s original mission. The site’s tone became more petulantly snarky and hectoring, both in articles (particularly news and trend pieces) and in what was left of the comments. Instead of being a place to find good work, it was a place where good work could occasionally be found. I think the staff and freelancers were trying to do the best they could under increasingly depressing circumstances, making the good they could, and it’s impressive how much they were still able to do. I don’t think the earlier AV Club would’ve had a regular column revisiting rom-coms, but Carolyn Siede’s bimonthly feature was completely in sync with the probing and fun analysis that made the site great a decade before. But the site’s slide toward boosterism on one hand and scolding on the other continued.

Even so, The AV Club was still a place to go, made in a place where it had been almost from the start. Until G/O Media announced they were moving its offices from Chicago to L.A. and essentially forcing longtime writers, editors and video producers to move as well, at their own expense. This was after G/O had already listed their jobs as available before anyone had actually left – the move to shove out staffers was as crude, obvious and insulting as any other G/O strategy. Those staffers are almost all gone now and numerous freelancers who have been writing for as long if not longer have left the site in solidarity as well. Freelance writers on the internet giving up paychecks is a hell of a ballsy move. But they didn’t want to be a part of whatever The AV Club will be in L.A., as it becomes a part of the entertainment industry it used to side-eye. At that point, is it even the same place? (If nothing else, G/O’s decision to take down two decades of images across all its sites makes the archives unrecognizable.)

***

Places aren’t permanent. The owner of a bar will sell the liquor license and retire to Florida. The Dissolve lasted two years before Pitchfork pulled the plug with no warning. Places are made by people, after all, and people change and move on. I’ve spent less time at The AV Club over the years in part because I’ve become less in tune with new pop culture and the site’s style of structural criticism about TV shows I don’t watch didn’t appeal to me anyway. But it still was a place where writers crafted pieces I liked and folks in the comments had funny and interesting things to say about them. People keeping a shared idea together for so long in one place is special, and someone taking that place away because of something even meaner than a profit margin is painful. “If you are lucky, you will get to be a part of something you truly believe in,” Emily St. James wrote in her final review of Slings & Arrows, an underseen TV show about a bunch of weirdos who try to make some meaningful culture and eventually are sold out by corporate goons. “If you are lucky, you will find a place you belong … If you are human, you won’t realize what you had until you don’t anymore. Suddenly, the thing that was at the center of your existence will become its opposite, an absence akin to a star collapsing in on itself and forming a black hole.”

It takes a real fucking prick to turn a good thing into its opposite and people smarter than I am have described how these pricks are not just evil but incredibly stupid. They’re incompetent using what they have to make money, let alone do good work, and the only idea they have to lead an organization is to run a bust-out. A shit-for-brains like Jim Spanfeller is only capable of destruction, and I’ve started to wonder if that’s been the point the whole time.

The bar is a place where you can be in the world but still control how much of yourself you put out there. And if you don’t like the vibe, you can always drink somewhere else. I have thought for a long time now that this is the best mode of the internet — a network of places where people can go and share but not necessarily reveal everything about themselves. Social media pushes back on that, encouraging the merger of what you do on the internet with your “real” life. It is living online in a large bright arena instead of visiting a place with casual anonymity and its own specific ambience. It’s a big space where anyone can jump on anyone else at any time – anybody can name or subject search to yell about something on Twitter – instead of a place that you actively have to go to, where a community has developed its own standards of interaction.

But even social media is still part of Web 2.0, and the power players want to move onto the next step — the Metaverse, of course, where you will be your offline self in a replacement world online. This new world will be brought to us through web3 and the blockchain, which is being pitched as decentralized and freeing but is mostly owned by a couple big rich players, the way the Metaverse is owned by the same asshole who owns a big place that everyone hates. People want to hang out at a place where they can have a good time, they’ve done that ever since an enterprising vintner started pouring wine in a seedy corner of the forum. And if only bad places are left after goons and gluttons destroy the good ones, they’ll have to hang out there. Good news for the goons who will find even more ways to make money off this, bad news for the rest of us.

Maybe this is an overreaction. Maybe I’m mad because I’ve seen this kind of destruction at places where I’ve worked, lived through the moronic decisions of ghouls who were contemptuous of people trying to make something worthwhile and of the audience who wanted to read it. And now those people have finally killed a fun place I had to go and get away from all of that for a bit, where I could hang out and goof off where nobody knew my name and where I could always discover something worth reading or hearing or seeing. A place that understood culture isn’t just something to be interchangeably pumped out by people who don’t feel and consumed endlessly by people who don’t care. Culture is local legends shit-talking fancy pretenders, it’s a bridge to understanding the past, it’s a way for your child to comprehend the world. It’s worth something, and when it’s not it’s given the thrashing it deserves. In the early blogging days, Phipps wrote about how the independent radio station he listened to growing up was going under, and how it didn’t just give him music, but an outlook on art. “They’ve always operated on a philosophy I’ve tried to bring to The A.V. Club: People want to find the good stuff,” Phipps wrote. “They just need a place to find it.” It’s still possible to make places like that, and people are still looking. But it’s worth remembering how this place used to be and how it was spoiled, and who did it and why. So pour one out and take one for the road. You don’t have to go home, but it’s not worth staying here.