The silent film era persists in the public consciousness mostly as a collection of moments and images rather than as whole movies or even scenes. Think about some of the most iconic visuals from that era: Orlok ascending the stairs in Nosferatu, Charlie Chaplin eating his boot in The Gold Rush, or the window gag from Steamboat Bill Jr. Perhaps this is the reason that Fritz Lang’s Metropolis still remains one of the most popular films from the silent era. It’s a film of giant sets and eye-popping visuals that have influenced sci-fi films from Star Wars to Blade Runner. When a complete copy was found in Argentina and released in 2010, it was greeted rapturously — finally, we could see the ur-text of cinematic science fiction in the way the director intended! But for all of its visual panache, the actual story of Metropolis, a hodgepodge of Jules Verne, socialism, and Christian symbolism, has a far more conflicted legacy.

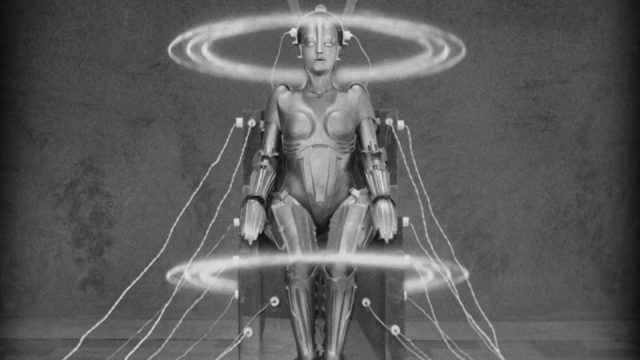

The storied design elements of Metropolis have become so influential that it’s hard to think of a sci-fi movie that doesn’t steal from it, either directly or indirectly. The movie still looks fantastic today, with incredibly intricate model work, clean lines, massive sets, and perhaps the most iconic image in silent movies, the Machinen-Mensch (played by Brigitte Helm, who also plays Maria, the film’s female lead). An early shot of worn-out workers walking home in lockstep through their subterranean city is still breathtaking. And the scene where the Maschinen-Mensch transforms into Maria is a marvel of “how’d they do that?” cinema (specifically the floating rings. The actual face changing is very clearly a dissolve). Adjusted for inflation, Metropolis is still one of the most expensive movies ever made, and every penny of it is onscreen.

What often gets dismissed when talking about Metropolis, however, is the film’s narrative. The script has been equally influential, though in more subtle ways. The movie deals with a large-scale rebellion of the lower classes against their exploiters, and the film paints in broad strokes the battle between good and evil. With such spectacle on display, it’s a smart move by Lang and his screenwriter/wife Thea von Harbou to keep the plot as simple as possible. The film announces early on its major theme (“THE MEDIATOR BETWEEN THE HEAD AND THE HANDS MUST BE THE HEART!” reads the very first intertitle) and hammers away at that theme for the next two and a half hours.

To this end, Lang and von Harbou make heavy use of religious imagery. Beyond the obvious symbolism in Maria’s name, there are scenes where the protagonist Freder (Gustav Fröhlich) is menaced by the Seven Deadly Sins and another where a machine turns into the demon Moloch (which raises questions about why everyone is placing their trust in a guy who seemingly can’t stop hallucinating). Maria retells the Tower of Babel story, but changes its meaning from an explanation as to why people speak different languages into an allegory about communication breakdown between the working and capitalist classes. And of course there’s Robo-Maria’s infamous striptease, where Freder imagines her as the Whore of Babylon, in an all-too-literal representation of the Madonna-Whore Complex.

Unfortunately, Lang would come to regret making Metropolis. Its themes of workers and capitalists working together on an even playing field proved quite popular with the Nazi Party, and Hitler allegedly identified with Freder (perhaps it’s better not to ask why the complete film was finally located in Argentina). Tellingly, for a film about a worker’s revolution, the film doesn’t end with an overthrow of the existing order, and the hero comes from the capitalist class. While von Harbou ended up joining the Nazis, Lang fled to America, where he made Man Hunt, a film about a hunter who tries to kill Hitler. It is perhaps fitting that Lang’s contributions to Metropolis rather than von Harbou’s that have persisted in the public consciousness, despite her screenplay setting a template for future science fiction films to follow.