The Hamiltonaissance continues with Elizabeth Cobbs’ The Hamilton Affair, a historical novel that traces the lives of Alexander and Eliza (née Schuyler) Hamilton from late childhood to his death, and nearly hers–from 1768 to 1854. Cobbs began writing this long before Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical opened, and it’s both a strong work on its own and a good complement to Miranda. Hamilton is an American origin story, less a demythologizing of Hamilton’s life than a new myth of it; The Hamilton Affair plays its characters not as myths but as people living their lives as best they can while history goes on all around them. Doctor Zhivago serves as one good point of comparison, but even more accurate would be Greil Marcus’ and Peter Guralnick’s writings on Elvis. Miranda is like Marcus, exploring a myth and tying it to a broad American narrative; like Guralnick, Cobbs gives these figures back their lives, and history back its everyday action. Also, she gets the chronology right. (Disclosure: Cobbs is a former boss of mine and a great lady too, and I’m glad she brought this book to my attention.)

Although Alexander and Eliza dominate the cast of characters here, one advantage of telling this story in the historical-novel genre is how many other characters and social details can be conveyed. Cobbs shows the codes of social standing, sexuality, politics, and honor in multiple settings–there’s a distinction between Albany and New York behavior here. (She also has a Suzanne Collins-level appreciation of food and its rituals.) Her descriptions are direct and never lush and that allows her to create some fairly complex set-pieces, both in terms of action and emotion; the Battle of Yorktown and the Hamiltons’ wedding night are equally vivid and affecting here, if for completely different reasons. She’s entirely sympathetic to Alexander and Eliza, really to everyone, and part of what gives this book a historical charge is that sympathy. There are really no villains in The Hamilton Affair, just people caught up in a fairly merciless bend of history–the Revolutionary War plays throughout almost the entire first half of the novel, in tricky and lethal ways. A question that goes through everything here: how do you live for your family when there’s an entire country that needs you?

Cobbs catches many period details here, among them how language was a demonstration of learning and class; Eliza reflects that “a triple entendre was considered superior to a double no matter how inane,” and Cobbs enjoys a few non-inane ones herself. She conveys a lot of the social codes through Eliza, forever hyperaware of them and occasionally questioning of them too. She’s smart and not completely witty–that characteristic goes to Angelica Schuyler, and everyone knows it. Eliza comes across as more curious than anything else and just slightly not born for these times, a Jane Austen character who wound up in a Henry Fielding novel. You can feel that’s why these two crazy kids are right for each other: they are both outsiders. I didn’t realize until halfway through how much I was pulling for them to make it work. (It’s rare that a historical novel can make you forget the actual history, however briefly.)

With a time frame of nearly forty years, Cobbs allows her characters to develop, calling up lives rather than portraits. Alexander and Eliza both change and deepen over the decades we see them: he’s not thinking taxes and national banks right away; and her hesitant journey to reconciliation after his affair feels realistic and moving. In the early chapters, Cobbs conveys Alexander’s love of his mother and the loss of his inheritance as the most touching and defining aspects of his life; it furthers the idea that what successful men have in common is the love of a strong mother. The injustices and impoverishment Alexander sees as a child and merchant in the West Indies don’t turn him into a crusader, but an incredibly shrewd and precise operator. Perhaps Cobbs’ best and most insightful moment comes when Alexander writes his public admission of his affair with Maria Reynolds: “The prose flowed. The evidence was strong. Even at such a grim pass, he took satisfaction in his powers of persuasion.” That moment isn’t really arrogance, it’s the desperate confidence of a man calling a bluff, publicly, with the skill of a lifetime. (I’ve compared Alexander to Don Draper before, and this is an almost purely Draper moment.)

Alexander knows in his skin just how far one can fall, and he’s determined that won’t happen to America. He’s not motivated by self-interest and knows how much he has to avoid the appearance of profiting off of being Secretary of the Treasury, because that would limit his honor and his action. His conception of the good comes across as something felt, not the shining words of the Declaration or of Common Sense but as what could be practically achieved; he’s compassionate (too much so, and that’s what will land him in Maria’s bed, the first time anyway), practical, and incorruptible, an ascetic but not an idealist. (Reverse those terms and you have Thomas Jefferson.) He grows in a recognizable but not reductive way from the first chapter to the next-to-last; Cobbs avoids the mistake of too many historians in that there’s something about Alexander that can never be fully explained by the incidents of his life. People are like that and so are good characters.

Alexander Hamilton was the Founder without the grand tropes of freedom and individualism but the one with the knowledge of what had to get done, the most essential and least quoted. That set him apart and opposed him to the aristocrats, Jefferson and James Madison; Alexander says of “Jemmy” Madison “[he]’s incorruptible. He just doesn’t know how the world works. On his plantation, pheasants fly to the table roasted. Wheat grows in bales. Jemmy wouldn’t know how to saddle a horse or load a gun without a servant’s help.” From the first page, where he runs his mother’s store in the West Indies, to being Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander comes across as the busy COO of a midsized company (with a particularly squabbling board of directors and don’t get me started on the shareholders), occasionally trying to articulate a vision for the future but mostly dealing with the minutiae of the present:

The past month had been brutally busy. The Treasury Department released the stock of the Bank of the United States to economic applause and political scorn. Alexander set up a national coast guard to catch smugglers and collect taxes. He engaged a lighthouse keeper for faraway Portsmouth, wrote Mercy Otis Warren to praise her poetry, negotiated a loan for the nation from a group of Dutch bankers, and interceded with North Carolina to ensure pensions for disabled veterans. . .

. . .the work of just another month near the end of the quarter at the office, which happens to be a country and its future. It can’t be said enough (certainly I never shut up about it): for all the ideals of Toms Paine and Jefferson, without Alexander Hamilton there isn’t a country.

Recently, on the Avocado (the AV Club After Dark discussion board, and yes you should check it out), there was a discussion on solutions to toxic masculinity. To me, the answer to that has always been obvious: develop the healthy masculinities. Cobbs’ Hamilton provides a model of an intellectual man that we could use now: someone without the Woody Allen-like self-deprecation (that Orson Welles correctly noted was the greatest arrogance; thanks to Splint Chesthair for bringing this to my attention) someone who sees his intelligence as a way to serve his family, community, and country. He isn’t the Heroic Loner; he always sees himself, and to some extent he defines himself, by his relation to others. Hamilton’s passion (intellectual and sexual) is great, but it’s his responsibility that defines him and this masculinity the most.

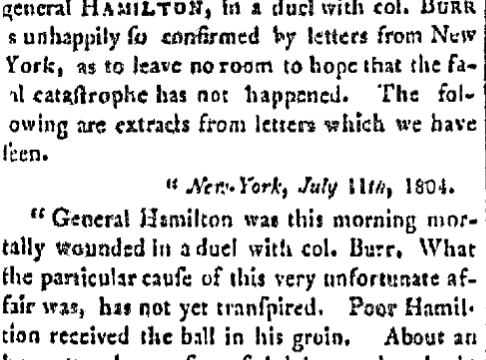

Cobbs skips ahead in time over several key points; the two parts of The Hamilton Affair cover, respectively, 1768-1781 (ending with Yorktown) and 1790-1854 (ending with the Burr/Hamilton duel in 1804 and then an epilogue-like final chapter). She gives us the personal dramas, and the political dramas when they impact the personal; for example, we hear Alexander decried as a monarchist because their children hear it. Jumping through time allows Cobbs to cover a great deal of history as recollection, which saves pages but more importantly gives a sense of things falling into the past as they happen. There’s a sense of people (Washington and Hamilton, especially) turning into legends even while they’re still alive, and the strangeness of that. That really hits in the final chapter, as Eliza watches the events of her life get consigned to another era while she still feels them, disappearing into history; that gets nailed down in a brief moment where she cannot accept an apology from James Monroe. The Revolution and the early years of American government had already become legend by then, as America moved steadily towards another war, but for her it was still memory.

Another thread that goes all through the novel finishes in that last chapter: the codes of honor that led to the duel. It figures in Alexander’s thoughts literally from the first chapter, conscious of his status as illegitimate, and Cobbs takes it way past any cliché of “boy of low birth makes good.” She understands how honor was the currency of an entire moral economy, how it determined who listened to you, what you could achieve in society (Alexander recognizes that war is one of his only chances to get ahead), where you could be in politics. Honor matters; it’s why he wishes for combat instead of writing papers under Washington. Cobbs makes it clear that if honor wasn’t a matter of life or death then, it was pretty damn close, and that makes dueling a rational practice. There are several duels in this novel before the last one, including the one that took Philip Hamilton; she also catches how Alexander was as afraid of taking life as of losing it. And in 1854, Eliza reflects “duels didn’t happen much anymore,” a sentence that carries an ache with it. (It calls up the bones on the ground in the epilogue of Blood Meridian, still one of my defining images of a past long gone.)

Another aspect Cobbs brings across very well, and one worth remembering, is the disunity of America in this time, a world where slaves, Indians, and all sorts of races and classes bumped up against each other. So many details bring this home, in action, dialogue, and description: Eliza gets adopted into an Iroquois nation at thirteen, the Schulyers continually slip into Dutch, Alexander has a black friend in childhood and another through his adulthood in America. (That last one is Cobbs’ invention, but an entirely reasonable one.) Like his work to create an America of “justice and prosperity,” Alexander and Eliza’s opposition to slavery was something felt, something lived, not a grand crusade but one more piece of everyday work for both of them. (Pretty much all grand moral crusades turn into millions of days of ordinary work when you look at them closely.) That disunified, messy social order continues unbroken through both parts of the novel, and it makes us feel how much the American Revolution wasn’t a revolution at all; the presence of slavery, the Hamiltons’ fight against it, and the end of the novel in 1854 remind us that America’s real revolution was on its way.

Novels remain perhaps the best medium for expressing a consciousness, and Cobbs’ comes through here in a very subtle way. She largely (but not entirely) avoids archaic speech and renders this world in a direct and descriptive way. It seems simplistic, a straightforward presentation of detail, until you start catching the details that aren’t straightforward at all: the presence of slaves, the mix of languages and peoples, the threat of disease. (In cities without modern sanitation, typhus and other illnesses were real dangers in the summer, so people who could afford it would send their families out of the cities then.) Reading this is like seeing a photograph of what you’ve only seen as a painting, where the surface tricks you into seeing it as ordinary. Cobbs gives the sense of seeing everyday life in our world just long enough to remind you that she’s not.

That gives The Hamilton Affair a strange kind of double historical consciousness. The world is definitely not ours, but the characters could be from it. Cobbs shows us both the past and a sense of the future that comes from it. (Thomas Pynchon, in his massive historical novels Mason and Dixon and Against the Day, tried to show us the past and all the possible futures embedded in those historical moments. That’s what makes them so fundamentally and necessarily strange.) That actually makes sense, because Alexander and Eliza both pushed the world from then into now. There’s no grand sadness about that, no sense that “oh boo hoo, these people were trapped by cruel circumstance”; neither of them were the kind of people who would just give up. Cobbs doesn’t judge the world of then for not being like the world of now but shows the work of people trying to change it, and “people trying to make a new world with imperfect tools” is a pretty good description of all history.