Once, in the mountains of Costa Rica, I spent an afternoon watching clouds. I didn’t play the game of “what shapes can you see there”; the clouds kept changing too quickly for that. What kept fascinating me was the experience of change, of holding on to a form and then shifting to another, quickly or slowly: the transformation of image over time. Consider defining music as the transformation of sound over time; these clouds were visual music, and it makes sense that it’s the closest thing I’ve seen to John Cage’s last work (he died between its completion and release), the film One¹¹*.

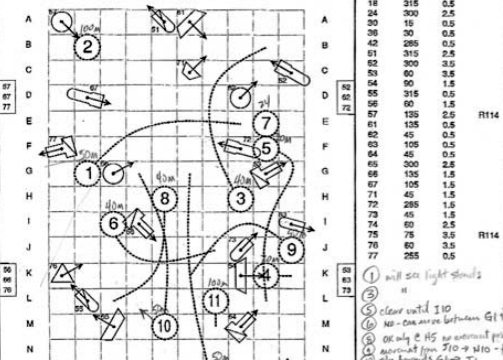

Although Cage produced works of art, dance, and poetry, he is best known as a composer, one of the great composer/theorists of the modern era; Brian Eno and Arnold Schönberg are his only equals there. His left a legacy not just of music but of thought about music, especially in his essay/poetry collection Silence. His most famous work was 4’33’’, a composition where a performer plays nothing for four minutes and 33 seconds, his principal legacy will be the dozens of compositions made by chance, which make up the overwhelming majority of his body of work. Cage called his method a process of asking questions, and then using chance (specifically, the I Ching) to generate answers, and his most important insight was “if the questions are not good, the chance operations are not good either.” His contribution to the composition was to set up the questions that would be answered randomly. One¹¹ was filmed in black-and-white in an empty studio in Berlin, with shifting lights on the wall as the only images** and no sound. Cage broke the movie into seventeen scenes and then used chance to determine the number of shots in each scene, and the position and motions of the cameras and the lights for each shot.

Obviously, One¹¹ dispenses with every aspect of narrative cinema, plot, character, setting, so on. What becomes clearer, and even more interesting, is how it dispenses with image too. Really the fundamental element here isn’t the image but the shot, the passage of time between cuts and dissolves. Much like Mark Rothko’s or Barnett Newman’s paintings, One¹¹ feels philosophical, like the demonstration–really the assertion–of a principle. Here it’s something akin to Plato’s description of shape as “the boundary of color” or the principle in physics that time is what keeps everything from happening all at once: here, a shot is the thing that keeps the edits apart.

Cage decided to give all the shots the quality of sound rather than cinema, and that may be the most necessary choice of One¹¹. Once he determined the number of shots, he further defined them and determined by chance the parameters of attack/sustain/decay/release, four terms that define the loudness of a sound over time–how the volume rises from zero, holds, decreases and then disappears. The shots don’t behave like we’re used to, by holding on an object (or objects) while something happens, or cutting between shots. One¹¹ has a flowing, wavelike sense of motion, of not just the light but the image itself moving in and out of our view. At the same time, the randomness of it keeps it from settling into any kind of rhythm and changes the feeling of time. Another decision, made during production, helps this: Cage instructed the camera operators to disregard some of the composition’s instructions and follow the light more closely. (Co-director Henning Lohner kept a diary of the making of One¹¹ and it’s deeply revealing, showing how Cage was equally occupied with the philosophy and practicality of making the movie.)

The use of lights and the black-and-white film stock create a kind of antiquated magic here. The feel of this film isn’t the hard edges of noir or the pure light and dark of Stan Brakhage’s hand-scratched Chinese Series, but the silvery, romantic light that Roger Ebert said was an essential component of pre-color movies. Because the movie comes from actual light exposed on stock, the images have the qualities of soft edges and the film grain and that gives the movie the feel of a dream or meditation from an age that’s already gone. (As a kind of tribute to that, and also as a joke, Cage added an ornate “The End” to conclude the work.)

Brakhage, asked why he didn’t sync some of his silent films to music–Stravinsky, for example–replied that then “the images would have Stravinsky’s continuity, not mine.” Cage stated that One¹¹ could be shown on its own or with the orchestral work 103, and when that’s done, it neatly gets around Brakhage’s problem, because neither work has any continuity. Much as Cage wanted in his music to “let sounds be themselves,” One¹¹ lets shots be themselves and suspends our ability to anticipate. We don’t know what’s coming, and that changes how we feel time. Looking back on watching this, I couldn’t tell you how long it was; it has the same quality of Anton Webern’s twenty-second or Morton Feldman’s four-hour pieces, of being a complete object, like a painting, rather than a process, like a movie.

The musicality of One¹¹ makes it pair perfectly with 103, because the orchestral work treats sound the same way the film treats shots. The music consists almost entirely of long tones from the instruments; there are only occasional beats of percussion and almost nothing quick, certainly there are no melodies here. (Again, no continuity.) For an American viewer, this music can be a little tricky; held tones without harmony are the music of suspense. At first, part of my mind waits for resolution here, or at least something to jump out; a good comparison would be the music just before the shower reveal in Psycho. Those with a different cultural background might hear the music differently.

A movie of quick cuts wouldn’t work nearly so well with this music, but putting the two together makes the shots seem like one more set of instruments, continually playing, and familiarizes what would otherwise be an alienating work. We’re used by now to ambient sound (and Cage was one of the pioneers of that) and the music gives a way in to One¹¹: this is an ambient movie. Eno said that ambient music must accommodate any level of attention: “it must be as ignorable as it is interesting.” Watch the movie the same way: leave it on in the background like a painting, and sit and watch when you wish. It can be ignored or studied as you choose, it will still be there. (Whenever he could, Cage insisted on easily accessible exits for performances of his works, so people could wander in and out.)

If we look for patterns, we find them; this is a defining characteristic of the human mind. Watching One¹¹ calls up images and they’ll be different for each of us; right at the beginning, there’s a pan across an ellipse of light that looks to me like the credit sequence in Alien. As the movie goes on, I look closer and begin to find patterns within the light, probably from the light source itself; I notice more when the light gets clipped by the edge of a wall, or the lights overlap. There’s a narrative here, but it’s not from the movie, it’s from my increasing attention through the movie. And there are the little shocks all the way through of a sudden cut, or percussion shot from 103, keeping the attention.

Meaning is part of human life, but not art itself; we bring meaning to the experience of art, for good and for ill. The joy of Cage’s music lies in its beauty, its wonder, not its meaning or interpretation. His chance works make nonsense of the idea of artistic intention; there is no more intent in the choices here than in the clouds of Costa Rica. (Perhaps when we see chance, what we’re really seeing is the intent of God.) In this last, unique work, Cage realized one more time one of his lifelong goals, to make art according to Ananda Coomaraswamy’s definition: “to imitate nature in the manner of her operation.”

*Beginning in 1987, Cage began titling almost all his compositions by the number of performers needed; the superscript differentiates between other pieces with the same number of performers. One¹¹ is the eleventh work for solo performer, since only a single projectionist is needed to “play” it.

**Now that’s painting with light–I got your codpiece right here, Thomas Kinkade.