In his first two albums, Elvis Costello achieved a sublime reconciliation of opposites by making a new sound from the oldest elements. Fusing catchy melodic hooks with meticulously crafted lyrics and arranging songs with a stripped-down reliance on traditional guitar, bass, and drum arrangements weaved through by sinister Farfisa keyboards, he released pent-up frustration at feckless romantic partners and the falsity of the culture at large. Listeners experienced the sweet cream of sixties power pop curdle into a toxic tsunami of recrimination. Costello’s early onstage persona combined the cool of the King of Rock and Roll with the foolery of a clown prince of comedy, stapling a Buddy Holly look (down to the suit and black rimmed glasses) to a Jerry Lewis-like spasticity. Armed with a barrage of quick-witted barbs aimed at the music establishment, Costello became a popular figure in the late-seventies New Wave rock movement.

When Costello’s music hit British airwaves in late 1977, rock and roll rebellion had been reclaimed in the three chord assaults of American bands like the Ramones and, in the artist’s homeland, the Sex Pistols and the Clash, that stripped music back to the basics. While much of this movement addressed disillusionment over Britain’s widening class divide in the wake of a decade’s long recession, the emergent racism of tribal youth gangs and the revival of the fascist National Front, it mostly confronted the middle-class consumerist value system emphasizing a “normal, quiet life.” Punk rock offered not just a soundtrack, but communities of varying ideological strains in rebellion against bourgeois hegemony in the form of Bacchanalian proletarian revelry; a political theater of iconoclastic nihilism. Another strain, the New Wave (as the music press liked to call it) drew inspiration from that movement’s energy while preserving the pop music “establishment’s” taste standards, couching social discontent in radio-friendly hooks, catchy beats, and humming keyboards. By the time Armed Forces dropped in 1979, Costello was ensconced in the latter camp, a songwriting pro with a Punk outlook looking to bite the hand that fed his suitably aggressive yet commercially palatable output.

Armed Forces is unmistakably British in inspiration, chock full of references to native cigarette brands and historical figures. The songs express an ominous unease at the resurgence of the country’s racist political movements in the late seventies, probing the reasons why a sense of personal dissatisfaction expresses itself in the demonization of the “other.” Many of the album’s themes, however, were inspired by the artist’s first tour of the United States. The blur of billboard and magazine ad slogans, heightened by partying and drug-fueled paranoia, left an indelible impact on Costello’s consciousness. Just before recording, Costello began living a double life with an American muse, straining his marriage and degrading his personal dignity. The tension from this personal, political, and cultural turmoil manifested itself on Saturday Night Live, where he spontaneously stopped playing his anti-Oswald Mosely screed “Less Than Zero” to segue into “Radio, Radio,” a blistering assault against the blandness of AM radio stations that, he felt, were declining to give him the airplay he, and the public, deserved. In rock stardom, the line between justifiable self-righteousness and rampant egotism is a fine one, and Costello seemed hellbent to cross it.

He captures this jitteriness on Armed Forces in impressionistic ellipses. Tight, sometimes electronically generated beats support melodies with the sing-songy catchiness of radio jingles. Out-of-tune organ notes and strange guitar loops sounding like computer malfunctions and sirens abound. Unlike the previous Attractions-backed release, This Year’s Model, which recorded and mixed the band at its rawest, Costello and producer Nick Lowe went for a more elaborate production inspired by Kraftwerk and records that Brian Eno was making with David Bowie and the Talking Heads. The arrangements eschew solos and instrumental noodling, emphasizing the melodic beauty of early British rock and Swedish pop bands like ABBA. The result was a record that was brutally efficient, subtly experimental, and undeniably listenable.

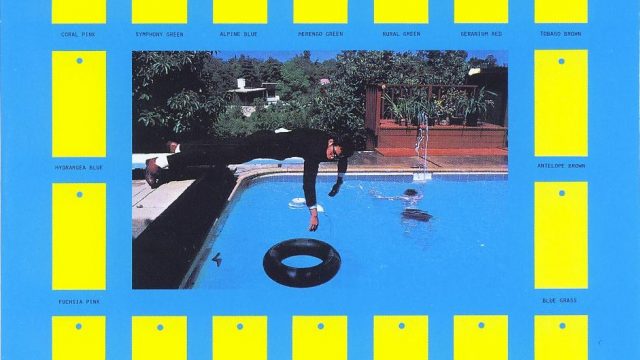

On the jacket sleeve of Armed Forces’ U.S. pressing, Costello and his band are drunkenly passed out on a diving board, with the words “emotional fascism” written in the border on top of the picture. This provides a clue to the album’s big theme: the dehumanization of personal identity in a mass society of violent alienation. More so than its predecessors, it mixes metaphors of romantic and sexual betrayal with images of political violence. Yet it surrounds this bleak theme with a deceptively poppy sheen. In recording the LP, Costello and Lowe import smoother, synthier sounds than its predecessors, instilling commercial radio likability with a subversive message. Yet its tight song structures and melodic yet spare orchestrations coil the tension of the song’s themes inwards. This record might not sound loud, but it delivers an intense wallop through compression.

The album begins with “Accidents Will Happen,” a mid tempo rearrangement of a ballad Costello wrote and began performing on the 1978 tour Its brief chronicle of a narrator witnessing his lover’s humiliation by a promiscuous partner, only to then see both himself and the courtesan lose their own dignity over time, is clear-eyed yet partially sympathetic to both parties (it’s thematically similar to the earlier single “Allison,” which Linda Ronstadt covered the same year) in its assessment of the loss of trust. Despite its poignancy (the line, “It’s the damage that we do, we never know/It’s the words that we don’t say that scare me so,” are the most confessional on the whole record), drummer Pete Thomas hits each shift from the verse into the chorus and bridge with a sharp blast on the snare drum, adding tension over Steve Nieve’s soothing synthesizer undertones. The song ends on a Beatles-esque harpsichord rift accompanying a repeated, anguished confession of “I know” into the fade.

Any hint of remorse soon dissipates, as the first “victim” takes control of the narrative. In “Senior Service” he takes aim at the one who led his lover astray by expressing a desire to, “Chop off his head and watch it roll into the basket.” In “Oliver’s Army” the character molds himself into a militarized masculine archetype who insulates itself from emotional intimacy while exacting pleasure from power. As a soldier, he jauntily travels all over the world for the thrill of the kill, kicking his heels to the slick flourishes from Nieve’s piano. By the next number, “Big Boys,” the physical sensation gleaned from martialing of the self becomes rote and unfulfilling (“I am starting to function/In the usual way/Everything’s so provocative/Very, very, temporary”). By the next song, “Green Shirt,” a midtempo number driven by electronically sampled beats, a three-note harpsichord intro and a terse, Wendy Carlos-meets-Mozart bit over the second chorus, the progression from vengeance to numbness instills feelings of paranoia (“I’ll send a begging letter to the big investigation/Who put these fingerprints on my imagination?”). Betrayal, in the form of treason to the self and the romantic “other” becomes explicitly tied to the political.

On the second side, the beats and keyboard notes assume a pointillistic, jerky motion resembling machinery running out of steam. The lyrics become more fragmented and vague, signifying the singer’s exhaustion from the delights gained from the mechanistic mastery of material gratification. In “Busy Bodies” the protagonist, following the consummation of a casual seduction, feels “temporarily out of action.” With “Moods for Moderns” he tells a casual fling that “There’s never been a ‘how do you do’/There’s never been an ending/So you belong to someone else and I will be a stranger just pretending.” As the hangers-on accumulate, the narrator adopts a cynical attitude towards the rituals of civilian niceties. The broken-down calliope waltz-step number “Sunday’s Best,” for example, disdains the fineries of a wedding that disguise bourgeois social hypocrisy.

In short, the album dramatizes the emptiness of new modes of male self-actualization that resulted from, and began replacing, those formed during the era of sixties idealism. Identities culled through the rising tide of militarism, post-austerity consumerism, and experiences gained from the carefree hedonism of celebrity status produce alienation and dissatisfaction. This coldness to the world outside of the self, Costello assumes, ultimately manifests itself in racism and misogyny. Combining Paul McCartney’s gift for melody and genre diversity with John Lennon’s penchant for connecting self-revelation to political engagement, Costello captures the drift towards Me Generation narcissism that drove the culture of the 80s.

Armed Forces makes this point most poignantly in its fleeting observations of other paths not taken by its characters. In the bridge that concludes the aforementioned “Big Boys,” the refrain of “She’ll be the one” is answered with attributes that make the object stand out from the pack, only to be ultimately crossed off and, to quote the opening song, “add[ed] to [his] collection.” Costello fleshes out the concept iin the ballad “Party Girl,” which acknowledges the singer’s desire to get to know the subject of a casual assignation better and his ultimate inability to devote the time to nurture the relationship. “Two Little Hitlers,” the LP’s closer (in the British pressing), offers a bitter rejoinder to “Accidents Will Happen.” The lovers are reconciled, but resigned to the ashes of bitterness and serial infidelity in the lines “You call Selective Dating/For some effective mating/You thought I’d let you down dear/But you were just deflating/I knew right from the start/We’d end up hating/Pictures of the merchandise plastered on the wall/We can look so long as we don’t have to talk at all.” As a chronicle of chain adultery in the age of mechanical reproduction, it seems fitting that the concluding song predicts the internet.

The album’s controlled chaos failed to contain the turmoil of Costello’s personal life. The debauchery that inspired the album carried on with disastrous results. The negative publicity generated from a racist comment Costello made in a bar fight (now euphemistically called “The Ray Charles Incident”) overshadowed the album’s message. The following year, as if to atone, he released Get Happy!!, an even more compressed collection of twenty songs, heavily influenced by American R&B, with an average running time of 140 seconds. This album was loud, brash, and sloppy, with slurred vocals and a hurried, blunt mix. Whereas Armed Forces turned its intensity inward, expressing itself in a disciplined pop formalism, the follow-up burst that energy outwards, playing soul music with punk abandon. By 1981, his marriage finally collapsed, and the sustainability of his image remained in doubt.

A year later, a more contemplative reminiscence of this era emerged in Imperial Bedroom, an album whose horn and string sections, coupled with a number of torch ballads, gave off a Sgt. Pepper vibe, thanks in some part to Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick’s production. It chronicled the dissolution of a marriage that was entered into too young and damaged by a morally compromising ingénue. It chronicled how the suspicion of infidelity and deception tears at the idealism of youth. It began the phase of Costello’s career that has more or less defined his present image: that of a scholar/practitioner in the art of popular song; the musical equivalent of Martin Scorsese. Last year’s model of the Angry Young Man had given way to someone more rested, leaving behind the pugnacity of adolescent arrogance for a introspective yet luscious pop approach. Costello would continue to make some fantastic albums over the years, but none that delivered musical complexity with the ruthless economy of Armed Forces, the record that summarized the beginning phase of his career yet pointed him on the path towards artistic maturity. He had up to this point never made a release so firmly elaborate and thematically coherent, and he would never tether these qualities as effectively again.