Spoilers for Hot Fuzz and Fargo follow

Edgar Wright’s modern comedy classic Hot Fuzz, which turns one decade old in a short span of months, is a film that is built upon references to other movies. This is not to say that the movie is derivative — it positively pops with the sensation of invention — but it is simply a fact. The climax is an explicit visual quote of Point Break, Chinatown gets paraphrased, and even the Jackie Chan vehicle Super Cop is name-checked. Wright even fits in music that only appeared in the trailer for Lethal Weapon, simply because he grew fond of it as a teenaged cinema projectionist in Somerset. The film embraces its indebtedness to its ancestors and in doing so provides the audience with additional layers of fun that go beyond its already-amusing plot twists and character turns.

But one of the most dominant antecedents of Hot Fuzz is one that isn’t quoted in the film and isn’t name-checked by the characters; a film whose music doesn’t appear in Hot Fuzz or have its DVD case shown in the background of a shot — no, one of the predecessors who shadow looms most notably in Wright’s film’s presence is Joel and Ethan Coen’s 1996 film Fargo.

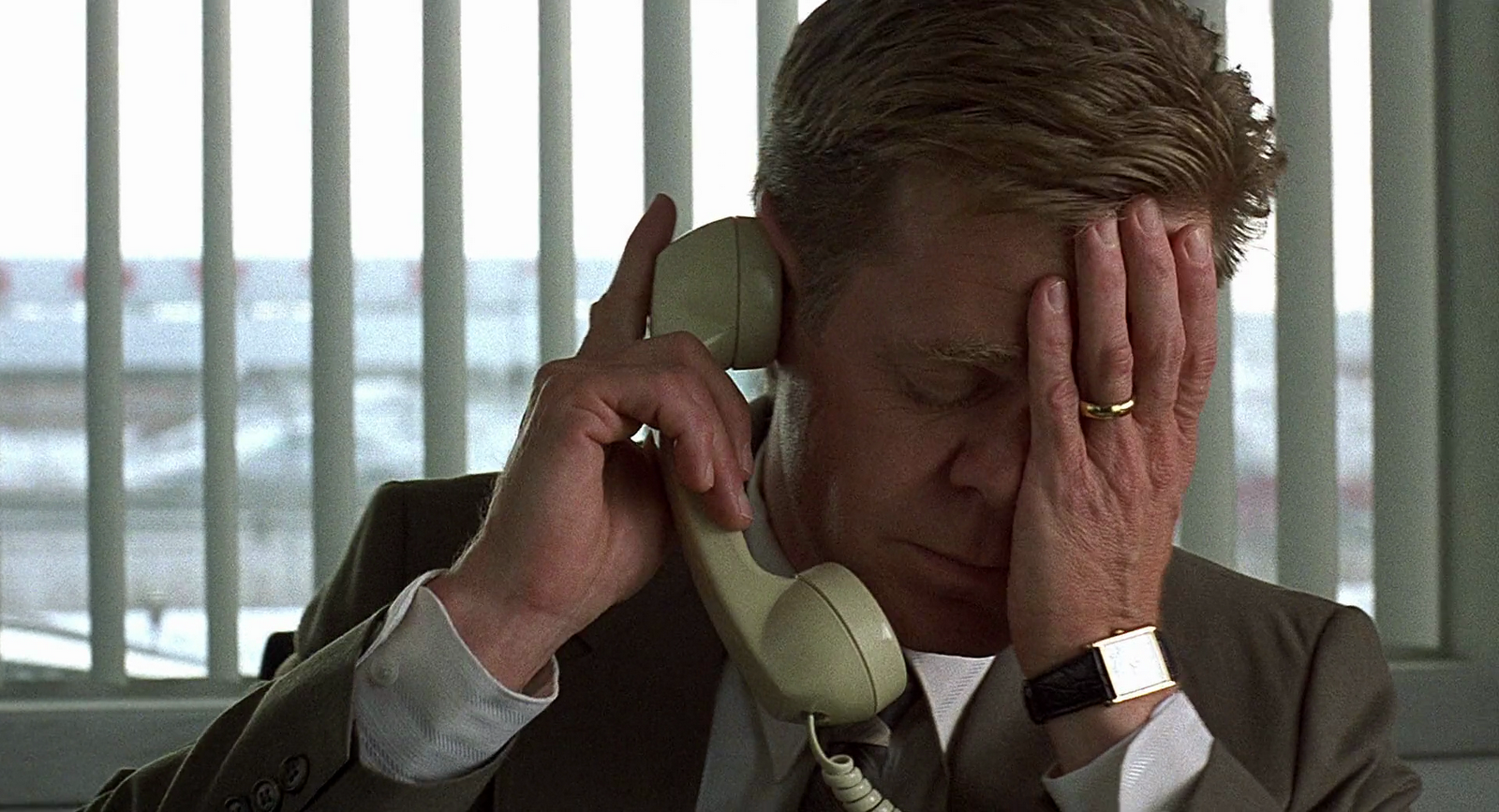

Now, I’ve floated this idea before, though many were unreceptive to it, but the spiritual similarity is undeniable in a clear-eyed analysis. Both films are about clever inversions of Hollywood cops-and-robbers morality tales, and though the explicit targets and settings are quite different, they are nevertheless drawn from the same impulse, the same kind of worldview. Fargo is the story of a little man, Jerry Lundegaard, a suburban Minnesota car salesman who seems dwarfed by everything — by his gruff, imposing father-in-law, by the natural enormity of Mother Nature’s Midwestern snowstorms, even by his own winter coat. He’s the kind of man that the politicians and the media imagine to be the average American — Protestant, working a 9-to-5 job, with a wife, kid and/or kids and an unwillingness to look like an outcast. Of course, this being a Coen Brothers film, greed will inevitably rear its ugly head. Y’see, underneath his meek, mundane exterior, Jerry Lundegaard (excellently played by William H. Macy in his breakthrough role) has an inner darkness, a ruthlessness, an inclination towards lying, towards deception, towards betraying others in order to get ahead. Only they can’t find out about it, y’see. He doesn’t want there to be any ugliness, any confrontation. The film begins when Lundegaard shows up late to a meeting with two out-of-town crooks, Carl and Grimsrud. One of the first phrases out of his mouth is “I’m sure sorry.” But he isn’t really sorry. But he knows that he can’t show up late to a meeting, even a meeting that initiates a criminal conspiracy, without apologizing to the other parties involved. It just isn’t done. Not in Minnesota.

Initial pleasantries aside, Jerry humbly proposes a scheme to Carl and Grimsrud — they’ll kidnap his wife, make it look like a hostage situation, and then when Jerry’s wife’s wealthy father coughs up the ransom money, Jerry and the two hoodlums will secretly split it and none shall be the wiser. Afterwards, Jerry will presumably live happily ever after as a picture of suburban social success, having made himself a small fortune and impressed his father-in-law with his resolve in the face of crisis.

This does not happen.

In Fargo, the crimes that spiral out of Lundegaard’s deception are not crimes of passion, nor crimes of necessity — Jerry is in debt but not fatally so — but are instead crimes of social striving. Jerry doesn’t need the money that bad, but what he does feel he needs is the reputation of being a successful businessman, a pillar of the community, an All-Around Swell Guy. And when all is said and done, seven people are dead, including Jerry’s wife, and he’s hauled off to prison, leaving his preteen son without any visible family. And it was all supposed to be a “no-rough-stuff” type deal, as Jerry says.

What is it that keeps all this darkness hidden for most of the film? Jerry’s not especially good at lying, not especially good at being a criminal — why isn’t he just trotted out in handcuffs five minutes in? The answer is simple: Minnesota Nice.

In the Minnesota of Fargo, you’ve got to be polite. You can’t use dirty words. You can’t call someone out on their bullshit. If you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all. Avoid the unpleasant, embrace the pleasant, no matter what the truth is. This is why Jerry can’t tell his wife about his money troubles, it’s why he has to work outside of society in order to solve his problems, and it’s why he’s able to sell his customers on hidden fee ripoffs and other such duplicitous business practices — so long as he smiles, shakes your hand, and says the right pleasantries, he must be telling you the truth, right? He’s sure actin’ like it.

Eventually, all of Jerry’s duplicity and deception shall come out, but at first we only see the consequences on a small scale. In a scene that plays out like Jerry’s scheme as a microcosm, Lundegaard tries to wriggle out of an awkward encounter with a disgruntled customer who got sold a car at a price higher than he agreed to it. The customer is pushed to his edge by Jerry’s glad-handing and grinning, and eventually tells the truth. As the Coens’ script puts it:

You lied to me, Mr.

Lundegaard. You’re a bald-faced

liar!

Jerry sits staring at his lap.

CUSTOMER

… A fucking liar.

This isn’t the only instance of surface-level niceness working as a shield for Lundegaard’s crimes. Later, in a scene that will have drastic consequences, Police Chief Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand in her most iconic performance), who is investigating the murders that have occurred in the wake of Jerry’s miscalculated kidnapping plot, visits Jerry at his office, inquiring if a brown Ciera Cutlass (the car used by Grimsrud and Carl) was missing from Jerry’s lot. The scene is brief.

MARGE

Uh-huh. Well, I’m a police officer

from up Brainerd investigating some

malfeasance and I was just wondering

if you’ve had any new vehicles stolen

off the lot in the past couple of

weeks – specifically a tan Cutlass

Ciera?

Jerry stares at her, his mouth open.

MARGE

… Mr. Lundegaard?

JERRY

… Brainerd?

MARGE

Yah. Yah. Home a Paul Bunyan and

Babe the Blue Ox.

JERRY

… Babe the Blue Ox?

MARGE

Yah, ya know we’ve got the big

statue there. So you haven’t had

any vehicles go missing, then?

JERRY

No. No, ma’am.

MARGE

Okey-dokey, thanks a bunch. I’ll

let you get back to your paperwork,

then.

And she walks out of his office, leaving behind a key part of the murder investigation.

See, the thing is, Marge is the real life version of the thing that Jerry pretends to be. She’s nice, genuinely. Sincere, genuinely. She’s an optimist, and she wants to believe in people, to believe in their goodness. It is, however, this quality that proves to be her great failing in this film. She believes, wrongly, that Jerry must be telling her the truth in that scene. She sees goodness in everyone, as part of her worldview, and she doesn’t easily summon up the willingness to be prickly, difficult, confrontational — when a confrontation is exactly what this moment requires. She lies too easily on “No, ma’am” and “Okey-dokey, thanks a bunch” when suspiciousness, mistrust, and cynicism would be what would allow her to solve the mystery easier and earlier, and in doing so, perhaps save the lives of the several people who will die after this scene, including Jerry’s wife, Jean, who will wind up at the close of the film murdered and very likely raped.

In a sense, Marge’s optimism and niceness are commendable, and certainly that’s how most fans of the film have interpreted her character — as a hero, a symbol of good, etc. Her closing scene with her husband Norm, tenderly resting alongside each other in bed, is both warm and welcoming. But it must be acknowledged by the close observer that Marge’s world is not the world of Fargo. The world portrayed by the Coen Brothers in the film is a lot meaner than Marge, a lot uglier. It is a world that takes advantage of the culture of niceness that Marge hails from and Jerry hides himself in. “Minnesota Nice,” the film illustrates, is fine and dandy on its own, but is just as often as not merely a cover for darkness and depravity, a facade that fools the kind-hearted people like Marge Gunderson who willingly submit to it, a toxic culture that shoves you into a wood chipper while saying “Ah, gosh, excuse me.”

So what does all of this have to do with Hot Fuzz?

Hot Fuzz also takes place within a culture of niceness, a picturesque small-town setting that is the comically unlikely spot for a crime thriller — though in this case, that “crime thriller” is more Jerry Bruckheimer than James M. Cain. Sergeant Nicholas Angel (Simon Pegg), an uber-competent London police officer with a sterling record, is transferred against his will to the cozy countryside village of Sanford, where his high-velocity style is an awkward fit with the town’s sleepy slowness. But gradually, Sergeant Angel notices a series of bizarre deaths and unexplained happenings that seem at odds with the village’s reputation as a model community, the “Village of the Year,” with little crime and even less unpleasantness.

Sanford’s rural friendliness and Little Englander-quaintness are the TransAtlantic counterparts to the Minnesota Nice phenomenon, and they serve a similar, though exaggerated, purpose within the criminal conspiracy plot of Hot Fuzz. Through his investigation, Nick Angel realizes that the seemingly “accidental” deaths that occur in Sanford are in fact grisly murders orchestrated on behalf of the smiling-but-sinister “Neighborhood Watch Alliance,” a coalition of the village’s leading citizens — respectable figures like the neighborhood vicar, the town doctor, the charming supermarket owner, and even the head of the local police force. These murders — murders of embarrassing amateur actors, annoying street performers, and misspelling-prone reporters — are all intended to secure and solidify the town’s reputation as a pleasant, perfect place to live. They are all justified, no matter their brutality, by the fact that they are committed for “The Greater Good.”

They are, in essence, killing to stay nice. Or rather, “nice.”

While the crimes of Jerry in Fargo are not on the level of Grand Guignol grotesqueness as the murders in Hot Fuzz (my personal favorite was watching the hack journalist having his head crushed under a falling church spire), and while they are more characterized by their pettiness and grasping desperation than by the comically complex conspiracy of Hot Fuzz, at their heart the criminal plots in both films are sprung out of the same well of darkness, a willingness to do anything, to go to any lengths, no matter how despicable, in order to preserve the culturally-mandated status quo of well-mannered courtesy and picture book pleasantry. Both the village green of Hot Fuzz and the snow-covered parking lots of Fargo are covering unwanted layers of blood.

Obviously, the two films vary greatly. They vary in terms of style — Hot Fuzz is a hyperkinetic Michael Bay pastiche of quick cuts and extreme closeups, while Fargo is filmed in a more subdued and quiet manner. They vary in terms of tone — Hot Fuzz, above all else, wants to make you laugh, and if it’s done that, it also wants to thrill you with well-choreographed action scenes, but Fargo is a more low-key character-based comedy. And it may be because of this variance in tones that the two films, despite dealing with similar themes, come away with rather different takes, or “messages” if one wants to be Stanley Kramerish, on those themes.

In Fargo, the toxic culture of niceness is looked at, examined, but it is — ironically, given the plot — not directly confronted. The Coens, for whatever reason, seem too timid as filmmakers (at least at the time) to engage with the true darkness of the story, with the evil that their film acknowledges but does not follow up on. In the film’s darkest scene, Jerry has a talk with his preteen son after Jean is kidnapped. The son is, understandably, traumatized and terrified by the turn of events. The prospect of living without his mother at such a young age is a scary one. He stares at the wall of his bedroom while clutching his childhood teddy bear, while Jerry, the secret mastermind of the kidnapping, can only offer lies and platitudes. It is the last we see of the Lundegaards’ son in the film. By the end of Fargo, that boy’s mother is killed, his grandfather is killed, and his father has been arrested while trying to flee the state. The boy’s life is changed forever, and for the worse — effectively orphaned on account of his father’s greed and treachery. But it is up to the viewer to realize this. After the scene in his bedroom, there is not even a further mention, not by any character, of the Lundegaard’s son, let alone a visual acknowledgement of what his life will be like from now on. One can defend this by saying that the Coens expected the viewer to make the connection on their own because they were too subtle to make it themselves, but it simply doesn’t track; the total disappearance of cinematic recognition of this boy, the truest victim of Jerry’s crimes, is a failure of Fargo. It is a film willing to show the kidnapping of an innocent, to show the traumatic effect that kidnapping has on her child, and to follow through past her brutal murder and her husband’s arrest, but is unwilling to show the audience the effect that that murder has on the child. Fargo walks us up to the violence and the depravity, but doesn’t actually wish to confront all the effects of it: to do so would be too unpleasant, apparently. The film instead falls back on a beautifully-directed, beautifully-acted ending that leaves the audience with a grimly optimistic feeling, but only because the alternative has been denied to us.

Of course, Hot Fuzz is much more of a broad comedy than Fargo is, and it’s conclusion is sunnier — the Neighborhood Watch Alliance are foiled by Nicholas Angel and his sidekicks, and taken in without a fatality, and all the paperwork properly filed! But Hot Fuzz doesn’t possess the same pretensions towards expose and “this is a true story” truthfulness that Fargo adopts, and in doing so, is rather more true to itself, if only because its ambitions are less lofty.

There’s a scene in Hot Fuzz that occurs when Nicholas Angel is getting to know his partner, clumsy local copper Danny Butterman, who shocks Angel by seemingly “stabbing” himself in the eye with a fork, causing his head to erupt in gushes of “blood.” Angel is horrified but Danny laughs, revealing that he was just playing prank with condiment packets. The blood was just ketchup. Later, after Angel learns the terrible truth of the Neighborhood Watch Alliance, Danny saves him from being executed by pretending to stab Nick and carrying his “corpse” away. Of course, Danny and Nick — and the audience — know that what seems to be blood is just ketchup. This is the kind of thing that Hot Fuzz does. It shows you what might look like murder, like violence, like blood, but the audience can laugh at it because we know it’s just ketchup. Harmless, mild ketchup. The problem at the heart of Fargo is that, despite all its strengths, it cannot tell the difference between blood and ketchup, and fearfully leaves the audience to sort out the difference.