When it comes to Female Trouble, I am an outsider. I’m one of those heterosexuals living the “sick and boring life” Aunt Ida (Edith Massey) laments, having children and celebrating wedding anniversaries. When I escaped her third dreaded fate of working in a literal office it only allowed more time for my sickness, taking kids to dance class and mowing the grass. If ever a film were not made for me, it’s this murderer-inspired raunchy pisstake that goes out of its way to step on my well-groomed lawn.

Yet instead of feeling provoked, I’m delighted to witness these ids and the ideas. The film can’t help but channel the genial spirit of John Waters, a man who lives honestly outside the status quo. Waters has spent the most amount of time filming flaccid dicks and people eating dogshit of anybody who could charm my grandmother. His disdain for normalcy is inviting rather than accusatory. If you find the exploits of him and his friends weird, well, he finds you a little weird too.

Female Trouble demonstrates this disarming quality with its disregard for suburban hetero life. This is disregard in the sense of indifference without hostility. If I were to perceive it as any kind of attack on my lifestyle, I would have to construe its mere existence as an attack, because mostly the film shuts the door on good taste and has its own way. Female Trouble removes the baseline for comparison offered by the world of us normals.

The last characters to speak for decency in the classical sense are the parents of bad girl gone worse Dawn Davenport (Divine). Christmas morning – a time when the pressure for family stability is so great the stress creeps through the façade of even normals – gets upended when Dawn is denied her desired gift. “Nice girls don’t wear cha-cha heels,” her father (Roland Hertz) scolds, succinctly voicing a standard and Dawn’s failure to meet it. Watching the first time, I had no idea what cha-cha heels were and the movie wasn’t going to bother explaining it to me anymore than a football broadcast slows down to define a forward pass. The lack of cha-cha heels sends Dawn into a package-stomping rage and ends with the mother Davenport (Betty Woods) under the fallen Christmas tree.

I think it’s instructive (and hilarious) that Mom’s crushed form is shown twice, once in an insert where she just lies there unconscious and the second time writhing gently and moaning “Not on Christmas… not on Christmas…” Mom’s lying under a tree, presumably but not apparently injured, and her only thought is how this experience stacks up against the ideal Christmas.

This is pretty much the final word from anyone resembling a real-world authority figure (even the cops later in the film respond to an emergency like panicky video game avatars). The next person Dawn encounters is herself, in a way, folding the film’s world back on itself like an envelope sealing. Dawn hitches a ride with Earl who is also played by Divine and the two drive to the dump to have sex. This is also the last moment you can keep alive the idea that the movie is going to cut away or apply the brakes in deference to modesty. It’s not just that the scene features Divine performing cunnilingus on himself, it’s that the soundtrack features double-tracked ADR of Earl’s slurping noises and Dawn commanding “Eat it! Eat it!” with the vigor of a drill sergeant. One can picture Divine standing at a microphone, feel his focus on the words to the exclusion of anybody else in earshot.

Now sealed off from recognizable cues of decency, the film creates a normality vacuum where there’s nobody in on screen to look aghast when Dawn emotes about locking her daughter in a room and beating her with a car aerial. Child abuse in the real world is not funny. But Dawn kvetching about the difficulties of being an abusive mother is very funny. Her onscreen friends are sympathetic but the humor relies on understanding Dawn is nothing like a fit mother. The film charitably assumes the viewer is not a psychopath and will get the joke. Any acknowledgement of uncrossable lines have to be found in metatext, like how Dawn’s daughter Taffy is played as a young child by a child for a scene where she is “merely” chained in her room (the game young actress can be seen slipping her own hands into the shackles) and then by a grown Mink Stole as the humor progresses to the grosser.

Replacing Dawn’s parents as the adults in the room are oddity impresarios Donald and Donna Dasher (Waters regulars David Lochary and Mary Vivian Pierce). The Dashers conduct themselves like royalty despite being groomed like poodles emerging from a costume trunk. They parody politeness when Dawn offers a spaghetti dinner with or without cheese. Donna makes sure to say “please” when she asks for two chicken breasts instead. Donald takes a small portion (with cheese, please) but makes sure to point out he’s doing so to be polite. Yet Dashers revel in Dawn’s disgusting performances. It’s a clear affront to good taste when Dawn pauses mid-swing for a picture before smashing a chair over Taffy, but the false courtesy of the Davenports is crass on a parallel level. There’s something honest in overt bad behavior that civility doesn’t automatically provide.

Also Dawn maims an enemy. Let’s not pretend insincerity is the highest crime on display.

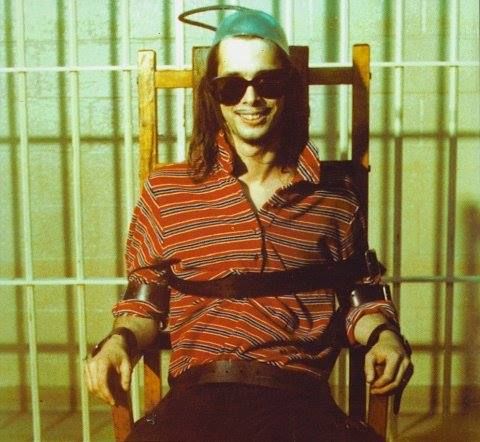

The film falters down the stretch when the young Waters’s obsession with fame by way of crime takes center stage, but it does give us one of the film’s funniest moments when Dawn abruptly shoots a volunteer willing “to die for ART.” The crowd, thrilled with Dawn’s exploits to this point, panics. Dawn is pursued by police, thrown into a women-in-prison movie and finally allowed a final rant before frying in the electric chair. Let the outrageous punishment fit the outrageous crime.

The relentless skewering of the bounds of taste without relief belies the Watersian ethos within: you won’t find this funny or outrageous if you don’t share a baseline expectation for humanity with the performers. It’s crucial there isn’t a normal person on screen. Were the film to allow in an avatar of the outside world, some head-shaking square or a clueless straight man (in the comedic sense), even as a comedic foil or a target for insults, it would open the whole conceit to the outside and its deviant characters would shrivel in the sunlight.

On the film’s commentary track, John Waters points out the old friends that filled out the cast and notes that the locations used are often the apartments and hangouts of these same people. It probably helps the translation to the humdrum corners of the United States that more than a few of his accomplices (the so-called Dreamlanders after Waters’s production company) were expatriates of the suburban middle classes, including Devine and Waters, drawn into the city of Baltimore by the counterculture. As parodies of popular film genres have shown, subversion benefits from familiarity with the topic being subverted. To give a guided tour below the standards of decency, it helps to have a strong sense of the standard to start with.