Side A can be read here: https://www.the-solute.com/inside-the-songs-of-inside-llewyn-davis-side-a/

1. “The Death of Queen Jane”

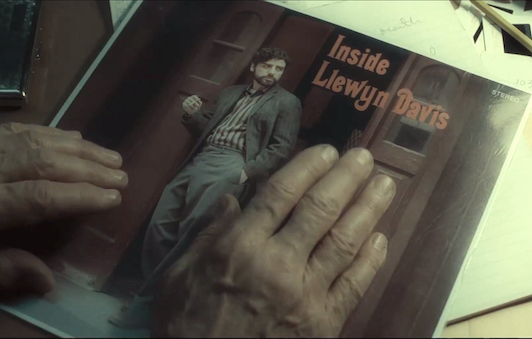

The scene: Llewyn has finally made his way to the Gate of Horn, and producer/promoter Bud Grossman implores him to play something from “Inside Llewyn Davis.” Llewyn obliges.

Key lyric:

” ‘Oh no,’ cried King Henry

‘That’s a thing that I’ll never do

If I lose the flower of England

I shall lose the branch too’ “

Historical Context: The oldest song in the film, “The Death of Queen Jane” recounts the (highly fictionalized) story of the death of the Queen Consort of England, Jane Seymour. Queen Jane was briefly the wife of the infamous Henry VIII, and died in 1537 due to complications from childbirth — giving birth to the King’s only “legitimate” son, the future king Edward VI. This song appears to have first appeared within a living generation of Jane’s death, and has proved popular both in the British Isles and in the United States. It is done in a fairly archaic English ballad style, with lots of lyrical repetition but a lack of clear verses or choruses.

Source: http://mainlynorfolk.info/cyril.tawney/songs/deathofqueenjane.html

Cinematic Context: This song is the culmination of a lot of Llewyn’s mixed emotions towards the the women (and children) in his life — what with all the complicated pregnancies. My personal interpretation (though the scene is open to many) is that while Llewyn recognizes the fact that neither he or Jean would be ideal parents at this point in their lives, in his heart of hearts, he can envision a future where the two of them live a “square” existence raising kids in the suburbs, far from the cold and heartache of Greenwich Village, like his sister Joy. In other words, he’s afraid that perhaps by losing “the flower of England,” his potential child with Jean, he will be losing “the branch too” — the possibility of a future with Jean. Certainly Llewyn must be in a dark place, emotionally, to play this song in his audition for Grossman; hardly a more uncommercial song choice could be possible!

Another footnote: Bud Grossman is clearly based on Albert Grossman, the real-life founder of the Gate of Horn club and the eventual manager of Bob Dylan, amongst others. When Grossman tells Llewyn that he’s open to placing him in a new trio he’s forming — two guys and a girl — so long as he shaves his beard down to a goatee, that is a sly reference to the fact that the real Grossman created the fantastically successful folk-pop outfit Peter, Paul, and Mary. In fact, Dave Van Ronk (the “real” Llewyn Davis) auditioned for the trio in 1961, but was rejected by Grossman for being too uncommercial and strange.

2. “The Roving Gambler”

This song, although it is on the soundtrack album, does not actually appear in the film (unless it plays really, really quietly in one scene and I somehow missed it, but I doubt that).

Nevertheless, I might as well recount some history. “The Roving Gambler” is a song of English origin, but was in fact initially called “The Roving Gamboler” — about a traveling highwayman, not a gambler. Something apparently got lost in the journey across the Atlantic, but hey, that’s folk music for ya. This version is performed by one of the alumni of the ’60s Greenwich Village folk scene: John Cohen, founding member of the New Lost City Ramblers and a noted musicologist.

Source: http://home.comcast.net/~yragb/cas/bk-gmbl1.html

3. “The Shoals of Herring”

The scene: Llewyn visits his elderly, senile father, a former Merchant Marine, and plays this song for him.

Key lyric:

“Night and day the seas were daring

Come wind or come a winter gale

Sweating or cold, growing hot, growing old

Or dying”

Historical Context: This is a folk song that stretches the definition of what a “folk song” is. It was written in the far-flung year of 1960. Yep, that’s right — this song is as old to Llewyn Davis as Katy Perry’s “Roar” is to us in 2014. Which presents an anachronism in the film itself: recall that earlier in the film, Llewyn and his sister Joy talk about a recording Llewyn made for his parents when he was a kid, “The Shoals of Herring,” so it is meant to be a subtle callback when Llewyn plays it for his old man towards the end. Of course, there’s no way that Llewyn could have recorded “The Shoals of Herring” as a child, but Oscar Isaac’s performance of the song is so powerful that I’d scarcely wish to sacrifice it in the name of strict historical authenticity.

(Incidentally, one draft of the script the song mentioned is in fact “Ladies of Spain,” an old British sailor’s lovelorn lament for the warm company of Spanish ladies that would actually be possible for Llewyn to have recorded as a child. If I had to speculate on why the Coens replaced it with “The Shoals of Herring,” I would say that keeping “Ladies of Spain” would have probably over-emphasized the themes of lost love and long-gone women, and that the right choice was to stick with a pure seafaring song.)

Anyways, “The Shoals of Herring” was written by English singer-songwriter Ewan MacColl in 1960, but was reportedly taken from the words and reminisces of real-life English herring fisherman Sam Larner, who first went to the sea as a mere boy in the year 1892 — so even if the song itself would have been new to Llewyn Davis, the words are owed to a man who spent several generations and many long years on the ocean.

Source: http://mainlynorfolk.info/lloyd/songs/theshoalsofherring.html

Cinematic Context: Llewyn has come back from his micro-Odyssey in Chicago a slightly changed man. He’s less combative, a bit more resigned and accepting, but life is still willing to push back at him. He goes to visit his father and has a heartbreaking scene with him. Davis Sr. was from a generation of men who worked their whole lives and had nothing to show for it save for some old photographs, and now just “exists” in a nursing home, unable to speak or move. When Llewyn plays “The Shoals of Herring” he’s attempting to provide the old man some measure of comfort in his twilight years, playing a beautiful little song about a life of work that was nevertheless well-spent. And the song can provide some comfort to Llewyn himself too, as he’s soon to be shipping out in the Merchant Marines himself, giving up on Greenwich Village, on folk music, on the whole thing, the living from gig to gig, scratching a meager existence in pursuit of some artistic ideal. He might be becoming a “square,” but maybe there’s some peace in that. At least he hopes so.

And then life shits all over that.

Llewyn looks to be greatly moved by the music. As if his son’s performance is putting him through the wringer. But nope, he’s actually just having a bowel movement. So far in the film, Llewyn performance’s have either been either indifferently received (Bud Grossman and “The Death of Queen Jane”), calamitously interrupted (“Dink’s Song” at the Gorfeins’), used to annoy (“Green Green Rocky Road”) or just a commercialized lie (“Please Mr. Kennedy”).

Here he receives his harshest response yet. It seems that poor Llewyn’s “folk” songs are just not connecting him with his folks.

4. “The Auld Triangle”

The scene: A distraught Llewyn visits the Gaslight, where a group of Irish vocalists perform. Llewyn likes their sweaters.

Key lyric:

“And the auld triangle

Would go jingle-jangle

All along the banksOf the Royal Canal.”

Historical Context: The Irish lads on stage are the film’s version of The Clancy Brothers, complete with famous sweaters. “The Auld Triangle” was written by Irish playwright/poet/IRA volunteer Brendan Behan, who spent several years in prison after being convicted of the attempted murder of two police detectives. The song first premiered in 1954, during the performance of Behan’s play The Quare Fellow (“The Queer Fellow,” for those of the non-Gaelic persuasion). The play, set in a version of Mountjoy Prison (where Behan was incarcerated) detailed the final days of a condemned man, as well as the imprisonment of “The Other Fellow” an effeminate man, likely gay, at a time when homosexuality was a crime. The song opened the play and introduces many of Brendan Behan’s political themes and concerns.

Sources: http://www.bobdylanroots.com/royal.html

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/486319/The-Quare-Fellow

Cinematic Context: Llewyn is glibly dismissive of the performers — of course, Llewyn seems to dislike all the other musicians in the film, so there’s that. Is he sincere in his dislike? Or is he — and this is my interpretation — just angry at the world and lashing out, unfairly, out of pain and depression? Although, to be fair, the lead singer of the Irish band seen in the film has an unfortunate lisp which makes the song initially come off as comical before it settles into its milieu.

5. “The Storms Are On the Ocean”

The scene: A middle-aged musician from Arkansas, Elizabeth Hobby, plays her first show in New York. A drunk Llewyn, having heard that Jean slept with Pappi (the Gaslight’s sleazy owner) in order to get him a gig, finally cracks and heckles Hobby, dis-railing her performance.

Key lyric:

“I’m goin’ away to leave you love

I’m goin’ away for a while

But I’ll return to you somehow

If I go ten thousand miles”

Historical Context: Bits of this song (“Who will dress your pretty little feet? And who will glove your hand?”) are very old indeed, with roots in Scotland around the 17th century, but the main body of this rendition comes from The Carter Family, who recorded it during the legendary Bristol Sessions of 1927: essentially, the moment traditional American folk music turned into commercial country music. Elizabeth Hobby says this is a song she learned as a girl growing up in the Ozarks. This actually squares with the timeline of the film, unlike Llewyn’s “childhood” songs. The use of Carter Family songs in both Inside Llewyn Davis and O Brother, Where Art Thou? also marks the two films as cousins in musical sensibility.

Sources: http://www.lizlyle.lofgrens.org/RmOlSngs/RTOS-StormsOcean.html

http://www.lizlyle.lofgrens.org/RmOlSngs/RTOS-StormsOcean.html

Cinematic Context: For all the talk of Llewyn being “a fucking asshole,” this scene contains, for my money, the only outright inexcusable thing he does in the film — verbally attacking poor, unsuspecting Elizabeth Hobby. At other points in the film, Llewyn is combative and prickly, yes, but he’s not acting much worse than the people around him. Jean is upset with him (and with good reasons) but is also hypocritical and unreflective. The Gorfeins are well-meaning, but extremely insensitive to a guy who’s best friend has just died*. And you try spending hours in a car with Roland Turner.

Here, though? No excuse. Llewyn is distraught, and has had seemingly everything in his life, even the Gaslight, insult him, and takes his anger out on the last person who deserves it. Ironic that Llewyn, seemingly the folk purist out of his peers, should insult the only pure folk artist in the film, but there you have it. This is also where Llewyn proclaims that he “hates folk music” — we know this is a lie, but Llewyn’s complete inability to connect with others has lead him to lash out against even his trade. He pays for it in the end, of course.

*The Gorfeins are also not Mike’s parents. There’s no evidence supporting that, and the dismissive way Jean says “I don’t hang out with the Gorfeins,” is all the evidence I need to say that they’re definitely not the grieving parents of a beloved friend.

6. “Fare Thee Well (Dink’s Song)”

The scene: The beginning has become the end, and Llewyn performs (finally) the signature song of Timlin & Davis.

Key lyric:

“One of these mornings

It won’t be long

You’ll call my name

And I’ll be gone”

Historical Context: See Part A! This version, however, musically owes a lot to Dave Van Ronk’s own version of “Dink’s Song,” also done in waltz-time.

Cinematic Context: Oscar Isaac makes a serious case for the world of “Harrison Bergeron” in this scene. Because if this one guy can act like that and sing that well, what hope do the rest of us have? Llewyn finally, with this song and “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me,” connects with the audience, prompting him to smile and say “If it was never never, and it never gets old, then it’s a folk song.” In this soul-chilling interpretation of the old song, Llewyn finally reaches something of the inner peace, the satisfaction he’s been searching for the whole film.

Notice the important changes in lyrics (taken from Van Ronk’s version), implying that Llewyn has, in fact, accepted Mike’s death and is ready to move on. The “key lyric” mentioned above is nowhere to be found in the version that plays near the beginning of the film. The Timlin & Davis version also features as its final verse the lyrics “Sure as the bird flyin’ high above / Life ain’t worth living without the one you love,” while the final version ends with the more hopeful “If I had wings like Noah’s dove / I’d fly up the river to the one I love.” Llewyn has been to hell and back, been thrown out on his ass, embarrassed, and abandoned on the side of the highway. Now he’s ready to move on.

But will the world let him?

Maybe. The idea of folk music as *folk* music gets complicated here. The audience appears to be deeply moved by Llewyn’s performance. Maybe he can reconnect. Of course, he also gets beaten up in a back alley by the kind of Arkansas traveler that gets folk songs written about him, so maybe he’s doomed to relive the same punishments over and over. It’s final lines of the film are “Au revoir.” An interesting choice of words. It’s a goodbye, a farewell, but it also means “until we see each other again.” Maybe Llewyn can move on, maybe he can’t. He’s reached the end, and it’s the beginning.

7. “Farewell”

The scene: A scruffy-looking young man with a guitar and harmonica contraption is led on stage after Llewyn finishes his set. His voice is quite scratchy and nasal, but the song is pleasing enough. Maybe he’ll have a future in folk music.

Key lyric:

“Though the weather is against, and the wind blows hard

And rain, she’s a-turnin’ into hail

I still my strike it lucky on a highway goin’ west

Though I’m travelin’ on a path-beaten trail”

Historical Context: In 1960, a 19-year-old University of Minnesota student named Robert Zimmerman, dropped out of school to move to New York and visit his idol, songwriting icon Woody Guthrie. By February of 1961, he was calling himself “Bob Dylan” and playing his first gigs in Greenwich Village clubs. Within a few years, he would be a living legend.

The song “Farewell” was first recorded by Dylan in early 1963, and that recording appears in the film, though he based it on a traditional English song called “The Leaving of Liverpool,” about a sailor leaving behind his darling in Liverpool for the sunnier coasts of California, though he promises to be back someday. Dylan’s song is much more vague and ambiguous in detail that the English one, which was a “fore-bitter,” meaning that it was sung by sailors who were off-duty, rather than as a rhythmic work song.

Source: http://www.loc.gov/folklife/news/pdf/FCN_Vol30_3-4optimized.pdf

Cinematic Context: Even here, over the credits of the film, the themes of saying goodbye are present. And here, it’s not just a goodbye to Mike, and to Llewyn, and the world of the film, but also to the old world of Greenwich Village, the folk scene that was forever transformed by Dylan’s lyrical and instrumental innovations. Dave Van Ronk, the real Llewyn Davis, the ‘Mayor of MacDougal Street’, would have a long and fruitful career, but the coming of Bob Dylan would indicate that his music would from that point on be the music of the past, rather than a living body. It wasn’t obsolete, but folk music was now a part of history, rather than just being in conversation with it.

Additionally, the way the Coen Brothers and D.o.P. Bruno Delbonnel shoot Dylan is perfect: a beam of pale light hitting him in the exact right spot, making him appear to be a ghost or phantom, something untouchable and otherworldly. This is particularly effective when combined with the slightly muffled sound of Dylan playing that we hear when Llewyn stands outside the club — Dylan in this movie is not really an individual person so much as some kind of spectral force.

8. “Green, Green Rocky Road”

The scene: This song plays over the remainder of the credits.

Key lyric:

“Howlin’ ‘green, green rocky road’

You promenade in green

Tell me who you love

Tell me who you love

*coughs*”

Historical Context: See Side A. This particular recording is a live one, and is what I like to call a “twist ending” song — where you listen to the entire song before you hear applause and realize it was recorded live.

Cinematic Context: The Coens very well understood that you can’t have an entire film devoted to a film a clef version of Dave Van Ronk and *not* feature Dave Van Ronk. Here we can compare Oscar Isaac’s soulful vocals with Van Ronk’s croaky swallowing the song — and I mean that in the best possible way. With Dylan having led us to the credits, Van Ronk leads us out of the theatre, an altogether fitting and appropriate song choice to end a film full of them.