SPOILERS FOR INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS FOLLOW:

1. “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me”

Scene: The opening scene of the film — Llewyn performs this song at the Gaslight Cafe to a good audience reaction, and concludes, with a slight smile, by saying “If it was never new, and it never gets old, then it’s a folk song.”

Key lyric:

“Put the rope around my neck

And hung me up so high

Put the rope around my neck

Hung me up so high

Last words I heard ’em say

Won’t be long now for you die, poor boy”

A note: Most sources I can find for the lyrics cite “Last words that I heard ’em say,” but my ears tend to hear “Last words that I heard her say,” an intriguing distinction. “Last words that I heard ’em say,” is expected, but the latter possibility opens up the floor up for more and stranger interpretations. A woman involved in some kind of lynch mob? Does she hold a personal grudge against the narrator? Does the use of the song reflect Llewyn’s feelings towards Jean, or maybe his previous girlfriend who moved to Akron?

Historical Context: This is an American folk song, apparently of Ozark origins, sometimes called “I’ve Been All Around This World.” It may have been written following the hanging of a man in the year 1870, at a time when vigilante “justice,” especially of the politically-motivated variety, was rampant. This version is nearly identical to Dave Van Ronk’s recording, that appeared on his 1963 album Dave Van Ronk, Folksinger. Get used to hearing Dave Van Ronk’s name, as he is the primary inspiration for the character of Llewyn Davis in background, appearance, and musical style, though apparently not in personality.

Sources: http://www.whitegum.com/introjs.htm?/songfile/I2VEBEEN.HTM

Cinematic Context: This song plunges us into the world of Llewyn Davis, and is performed in a stunning close-up by Oscar Isaac, photographed by Bruno Delbonnel for the Coen Brothers. Like the narrator of the song, who is apparently hovering in the moment just before his death by hanging, not quite amongst the living, not quite dead, Llewyn flits in and out of darkness and the spotlight, with the simple and steady rhythm of the song, played solely on Isaac’s acoustic guitar, keeping the balance between life and death, darkness and light, and perhaps most crucially, satisfaction and depression. If one of the key themes of the film is Llewyn’s search for some measure of satisfaction from his depressing life, if not quite happiness, than the opening performance is our introduction to that search — the song is a melancholic rumination on death, but Llewyn performs it with a light grin and a hint of humor. The look on his face is one of a performer reaching a degree of inner peace in the pursuit of his music. We won’t see this look on him very much for the duration of the film.

2. “Fare Thee Well (Dink’s Song)”

Scene: Llewyn wakes up in the home of the Gorfeins, finds the album that he recorded with his old partner Mike, plays it, accidentally lets the cat out, and rides the subway to Jean’s apartment.

Key lyric:

Just as sure as the birds flying high above

Life ain’t worth living without the one you love

Fare thee well, my honey, fare thee well

Historical Context: The oldest known version of this song was performed by a woman who was, appropriately, named Dink. She was a black levee worker in Texas, and was recorded by the seminal American music folklorist John Lomax in the year 1904. Her performance of the song is long since lost, the only physical record having been broken. Dink’s full name is unknown. She told Lomax that she was raising a son without a name, and that one day, she would go “up the river where I belong.” Dink, it would seem, survives now only in her song’s descendants. This version of the song appears to be an original and novel arrangement; it bears relatively little resemblance to Dave Van Ronk’s version, or the versions of his contemporaries, for instance Bob Dylan or Fred Neil’s version.

Sources: http://jopiepopie.blogspot.com/2013/04/dinks-song-1904-fare-thee-well-1942.html

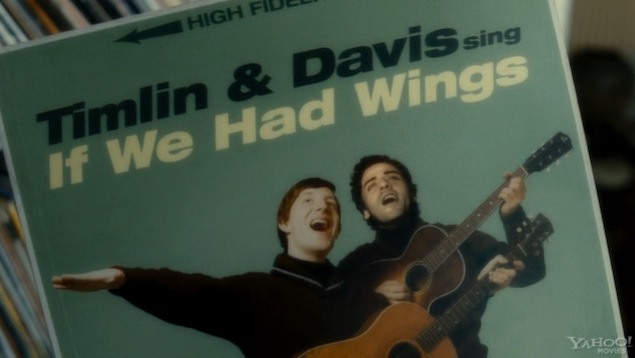

Cinematic Context: This is essentially the theme song of the film, fitting in its lyrics much of the themes and motifs: saying farewell (a word that appears, in some form or another, in several songs in the film), grief,and escape. The lyrics and arrangement in this version differ significantly from the rendition that closes the film, but more on that later. It is worth noting that despite the melancholic lyrics of the song, the recording is fairly upbeat and poppy. This fits with the cover art of Timlin & Davis’ album, If We Had Wings, featuring the two troubadours smilingly extending their arms in a faux-winged position. Later in the film, Llewyn will attempt to play the song while at the Gorfeins’ dinner party, but becomes overcome with grief when Lillian Gorfein tries to join in on harmonies, singing “Mike’s part.”

3. “The Last Thing On My Mind”

The scene: Troy Nelson, a U.S. Army serviceman and part-time folksinger, performs at the Gaslight, to Llewyn’s apparent dismay.

Key lyric:

As I lie in my bed in the mornin’,

Without you, without you.

Every song in my breast dies a bornin’,

Without you, without you.

Historical Context: Troy is a fairly transparent parody of folksinger Tom Paxton, and “The Last Thing on My Mind” is one of Paxton’s most famous compositions, appearing on his 1964 debut album, making the inspiration even more obvious to those familiar with the folk music scene of the ’60s.

Sources: http://www.allmusic.com/album/ramblin-boy-mw0000224316

Cinematic Context: Other than continuing the general tone of loss that pervades the film, “The Last Thing on My Mind” does not appear to directly comment on the action in the film. Perhaps there is meant to be a distinction between Llewyn’s affinity for traditional folk songs (read: real folk songs) and the newer originals of Troy Nelson and, eventually, Bob Dylan.

4. “500 Miles”

The scene: Jim and Jean join Troy on stage to perform this song — and the crowd at the Gaslight sings along.

Key lyric:

If you missed the train I’m on

You will know that I am gone

You can hear the whistle blow a hundred miles

Historical Context: The song known as “500 Miles” is copyrighted to 1960s folksinger Hedy West, but like many ’60s ‘folk’ songs, its origins lay in much older songs and musical traditions. Part of the lineage of “500 Miles” is the old Appalachian folk song “900 Miles,” which has been recorded by Odetta, Woody Guthrie, and Roger McGuinn, among others. The newer version of the song was famously recorded by Peter, Paul, and Mary, whose interpretation is clearly a visual inspiration for having Jim, Troy, and Jean onstage — Carey Mulligan is even given Mary Travers’ famous haircut with prominent bangs. Peter, Paul, and Mary will be alluded to later in the film.

Sources: http://www.secondhandsongs.com/work/8308

Cinematic Context: When watching Inside Llewyn Davis, one of the things to keep in mind is to pay attention not just to the songs, but also to the reaction to the songs. In this scene, Llewyn seems mildly bewildered as the crowd begins to sing along with Jean, Jim, and Troy. Jim and Troy have choirboy voices, and Jean sounds like an angel, ironically contrasting with her vinegar personality. Llewyn’s voice is a bit harsher and darker — although not nearly as unconventional as Dave Van Ronk’s singing voice. Does the crowd’s positive reaction to the trio’s performance indicate that the tides are shifting away from Llewyn’s perhaps more authentic folk style, and towards a more poppy style?

5. “Please Mr. Kennedy”

The scene: Llewyn, in bad need of cash, joins Jim and singer Al Cody for the recording of a new novelty single.

Key lyric:

“Got a red-blooded wife with a healthy libido

You’ll lose her vote if you make her a widow

And who’ll play catch out in the back with our kid?”

Alternate: “OUTER. SPACE.”

Historical Context: This is a long one. In 1960, three songwriters, Al DeLory, Fred Darian, and Joseph Van Winkle, wrote a comical song called “Mr. Custer” for novelty act Larry Verne. The song’s lyrics told of an American cavalryman serving under the legendary George Custer just before the Battle of Little Bighorn, who begs and pleads the general “Please Mr. Custer, I don’t wanna go.” Amazingly, that song went to #1 on the Billboard charts. A few years later, white Motown singer Mickey Woods recorded a “parody” called “Please Mr. Kennedy,” this time about a young man who begs JFK not to draft him before his sweetheart marries him. Around the same time, folk duo The Goldcoast Singers did their own version, a satirical political song about the early days of Vietnam. This version, written by George Cromarty and Ed Rush, is the one that is credited in the film. However, the “Please Mr. Kennedy” we all know and love (OUTER. SPACE.) is quite different from any of the above mentioned version; different enough to merit a Golden Globe nomination for Best Original Song, but derivative enough to be disqualified for an Oscar nomination.

Sources: http://www.thewrap.com/golden-globes-please-mr-kennedy-inside-llewyn-davis-justin-timberlake/

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/12/01/please-my-kennedy-inside-llewyn-davis_n_4344365.html

http://motownjunkies.co.uk/2010/04/25/140/

Cinematic Context: “Please Mr. Kennedy” sticks out like a sore thumb compared to the rest of the songs in the movie: precisely the point. Representing the artistically bankrupt yet commercial successful, the song manages to embarrass both Llewyn and Jim (who wrote it). It’s also hilarious (OUTER. SPACE.) There are a few observations of note, though. The lyrics chosen above, inventions of T. Bone Burnett, Justin Timberlake, and the Coens themselves, are possibly meant to reflect, subtly, the situation Llewyn Davis is in regarding the two unwanted pregnancies he’s gotten himself involved in. The song is also responsible for one of the more notable anachronisms in the film. The musicians go by the name “The John Glenn Singers,” obviously meant to be a reference to the astronaut John Glenn, who became the first American to orbit the earth in February of 1962 — a full year following the setting of Inside Llewyn Davis. In February of 1961, when the “John Glenn Singers” were recording their hit, John Glenn was just one of seven Mercury astronauts, who had yet to distinguish himself. A more realistic choice would be Alan Shepard, who in January of 1961 was chosen to be the first American to go into space.

(For the record, some other anachronisms: Llewyn walking by a movie theatre that is showing the Disney film The Incredible Journey, incredible indeed, seeing how that film wasn’t released until November 1963; Johnny Five boasting that he appeared in the controversial play The Brig, which wouldn’t be staged until May 1963; and few songs, which I will get into at a later point.)

6. “Green, Green Rocky Road”

The scene: Llewyn plays this while riding to Chicago in order to intentionally annoy the dozing Rowland Turner.

Key lyric:

“Hooka tooka soda cracker

Does your momma chew tobacco?

If your momma chews tobacco

Hooka tooka soda cracker, yeah”

Historical Context: Dave Van Ronk is said to have called this his “theme song,” and a live version by Van Ronk plays over the closing credits. It was copyrighted by Greenwich Village regulars Len Chandler and Robert Kaufman in 1961, but apparently has its origins in a black children’s folk song from Alabama.

Sources: http://mudcat.org/thread.cfm?threadid=27047

http://denisesullivan.com/2013/12/07/promenade-in-green/

Cinematic Context: Come on, you’ve got to work Dave Van Ronk’s theme song into the film somewhere. This scene is also notable because of what was mentioned earlier — pay attention to the audience reactions. So far in the film, Llewyn has either failed to play one of “his” songs (the aborted dinner party at the Gorfeins) or has compromised his identity to play commercial pap (“Puh-puh please.”) Here Llewyn is playing, but he’s using his music as a weapon, an irritant. One of the key motifs in the film is the idea that folk music is folk music — it’s supposed to connect you to other people. Unfortunately, Llewyn has had the problem — at least since Mike died — of failing to connect with others, and in this scene he seems to know it, using his music to bother rather than connect.