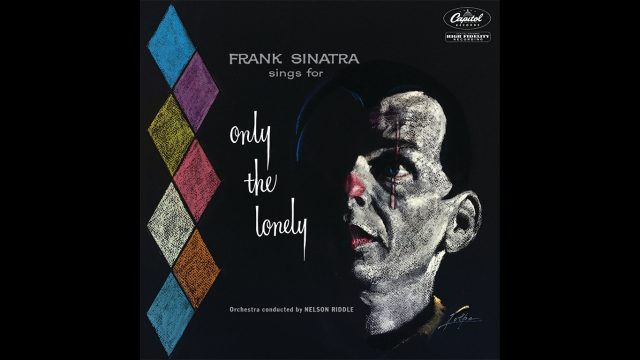

In October of last year, Only the Lonely was reissued in a 60th anniversary stereo mix. If you read the press release, you learn that in 1958, the original stereo mix was, at best, an afterthought—it was made to be listed to in mono.

Mono conjures up the nostalgia of hearing a crackly AM radio signal on a car radio through tinny speakers. Yet, as Damon Krukowski explains, even when stereo was available, mono was the preferred option, continuing through the sixties. The advantage: “With mono, the listener hears it exactly with the balance that the producer intended.” And, unlike stereo, mono “is the same whether you are to the left of the speaker or to the right”—it’s more democratic.

This issue is a sticking point with me, especially with Frank Sinatra. I want to argue that stereo mixes of most of his records sound more “dated,” as if, in retrospect, his records are the precursor to something better. It’s not just that a mono mix of Only the Lonely is as good as it gets at the time; more importantly, it preserves the groundbreaking aspect of the album: when we listen we are together alone: through which resonates its call to let go, to make a scene, even, to see how far gone you can get.

The title track sets the mood in impeccable fashion, featuring a bluesy riff threaded through a major seventh chord, which elicits a floating sadness, rather than one more grounded. Sinatra, his voice burnished by the weightless and eternal late-night hours, puts a golden touch on the last line:

And never let love go

For when it’s gone you’ll know the loneliness

The heartbreak only the lonely know

As hope is abandoned—this advice comes too late to save anyone who’s listening, who knows what the lonely know—desperation takes over, and we’re plunged into the slow burn of “Angel Eyes.” Sinatra returns to his old haunt one last time to tell his tale brimming with contempt for both himself and his fellow fools (especially bitter is “I got to find who’s now the number one”) before he disappears for good, his breath control mesmerizing as the scene fades.

Nelson Riddle deserves praise for his arrangements that ebb and flow, complimenting Sinatra’s uncanny sense of how close to be to the microphone at any moment. Riddle also takes advantage of Sinatra’s ability, like an actor, to hit his mark. The orchestra in “Willow Weep for Me” starts low and modulates upwards until Sinatra comes in on the note that begins the verse. It gives the song an unstoppable momentum which pushes back against any sense of wallowing in sentiment. A lesser singer would telegraph the obvious imagery here (I’m looking at you, Dean Martin!); Sinatra has the foresight to let Riddle do his job.

“Blues in the Night” goes in the opposite direction. The orchestra swoops downwards, which allows Sinatra, in a lower register, to draw out the sting of the “My mama done told me” platitudes about bad women: love, sadly, is immune to such advice. Yes, there’s blues in the night, and they’ll run you over like a freight train—Sinatra projects the moan of a lonely train whistle, then cuts it off mid-phrase to return to the words of the song. It’s a show stopper that has no equal in 1958 (The Genius of Ray Charles wouldn’t be released until a year later).

Sinatra is at the top of his game, and he takes an almost perverse thrill in his voice sounding as relaxed as someone’s thoughts in the middle of the lazy high of an afterglow. His voice, however, can retain a steely resolve which carries through the more conventional songs on the record. “Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out to Dry” unfolds the dark ironies that trace the same existential route as the songs on In the Wee Small Hours did three years earlier.

If we are alone together in the head spaces of the characters who populate the deserted streets of In the Wee Small Hours, in Only the Lonely, we are together alone, as songs, like “Angel Eyes,” are composed of fragments of speeches to an audience. At times, Only the Lonely could be a soundtrack to the passionate damage wrought in Some Came Running, released in the same year, starring Sinatra, Martin, and Shirley MacLaine, that floods with the waters unleashed by the dam break of 50s consciousness staged in Rebel Without a Cause. I think the mistake is to assume Sinatra sings only for a certain (read “older”) lonely crowd, when he could be singing for younger cats like James Dean too. Sinatra may not have understood alienation, but he felt it, baby.

The songs on Only the Lonely, while rooted in naturalistic settings such as late-night dives, veer away from how people really talk to amp up the dramatic feel. The starting point is a collective angst (together alone) that creates an individual stage for Sinatra. By now, he is so inured to the spotlight that he sings in character, yet makes these characters even more like him, as a cracked reflection of his well-documented failed relationships, while, at the same time, he becomes more like us. One reason for this transference is his dynamic range when in a softer register, which creates an intimacy that borders on, but does not cross into, the confessional.

Another reason is the song sequence that uses more traditional theatrical devices, such as the “why am I unhappy?” motif in “Spring Is Here,” to set up more challenging narratives such as “One for My Baby (And One More for the Road).” The orchestra shadows the saloon piano chords of “One for My Baby” as if it were the smoky, alcohol-drenched haze at closing time. Sinatra sounds like he’s so close to the microphone, he could be in the room with you. He dances through the syncopation of “I could tell you a lot/But you gotta be true to your code,” without losing the convoluted train of his character’s thoughts. Then he gets to the defining line: “You’d never know it/But buddy I’m a kind of poet.” And we’re all here to listen.