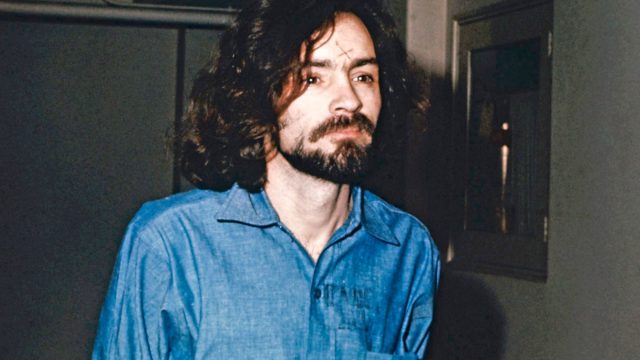

So Charlie’s dead.

I’ve been weirdly fixated on Charles Manson’s case for many years. I read Helter Skelter for the first time in high school, and I do feel it necessary to point out that my copy was used when I bought it, and that I did not read it to bits on my own.

But Charlie’s a metaphor. He is. He’s a metaphor for a lot of things. Our own personal darknesses, the dark side of the ’60s, whatever you want to call it. I suppose that’s part of why you get people insisting that he didn’t really belong in prison, which is nonsense on several levels. I mean, the most basic of which is California state law; conspirators are just as guilty under the law even if they don’t actually do any of the work.

Charlie is Polanski’s excuse. Polanski is a garbage person, people say, but after all, Charlie murdered his wife. (Those who know that Polanski was a garbage person before her death but forgive him for things blame the Holocaust.) Polanski apparently would not have been a rapist if Charlie hadn’t taken Sharon Tate from him.

Charlie was the boogieman, as he himself knew. A generation feared him. Between Charlie and Altamont, that was the end of the Sixties.

Charlie was keeping Leslie Van Houten in prison. She is frankly a poster child for rehabilitation, and for forty years, she has been asked what she’d do if Charlie asked her to kill again. The parole board recommended parole in September, but every time she comes close, someone asks what she’d do if Charlie—with whom she has had no contact in decades—asked her to kill again. Jerry Brown rejected her parole last time; he still has about two months to decide if he’ll let her out now.

Charlie is dead. And not before time.