Brief intro to Big Star: this Memphis-based power-pop quartet was led by Alex Chilton, trading in the deep croon he brought to the Box Tops as a teenager (check out “Cry Like a Baby” for a perfect example; “The Letter” is also a terrific song) for a raspier but more emotive vocal, paired with his sturdy Fender Stratocaster. Joining him were Chris Bell on guitar (along with Chilton the chief songwriter for the band), Andy Hummel on bass, and Jody Stephens on drums. Their star-crossed history is rather ironic for a band named Big Star whose first disc was 1972’s #1 Record: They signed to Stax Records right as that label was having serious financial problems, and those problems led to very poor promotion and distribution of their albums. A despondent Chris Bell left the band before their second album, 1974’s Radio City, although he still contributed on the album. Chilton’s personal crisis and demons led to the band’s third and final album taking on a much darker and more chaotic tone than their previous power pop; the record company shenanigans, along with the album’s wild deviation from the band’s previous work (it’s really a Chilton solo album) and Chilton’s personal problems, derailed the album’s release until 1978, three years after it was recorded, and even then under conflicting track listings, song selections, and even titles. (It’s alternately known as Third and Sister Lovers; the version considered definitive as the closest to the band’s intentions was released by Rykodisc in 1992.)

The band broke up after that and disappeared into obscurity; upon their gradual discovery and growth of their reputation by other artists, critics, and music fanatics, Chilton and Stephens reunited the band in 1993, replacing the late Bell and Hummel with Jon Auer and Ken Stringfellow of the Posies (a pretty good power pop band in their own right– I recommend the live acoustic version of “Flavor of the Month”). The band toured with this lineup off and on and released one more album in 2005 (In Space, which is… not as good as their previous work). The days of Big Star came to a permanent end when Alex Chilton passed on March 17, 2010, in his adopted hometown of New Orleans.

Now, onto the music.

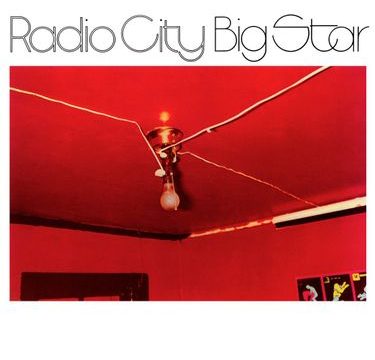

#1 Record and Radio City are inseparable to me, having only come onto both after their re-release on one CD (which was in 1992; it wasn’t until college that I discovered them). Still, though, we’re sticking to the one released in 1974, and as well as they work together and as much as they’ve provided a blueprint for power pop for decades, there are clear distinctions between the two albums.

Radio City is the second and more mature album; much of #1 Record is given to more plainspoken, straightforward sentiments (think “My Life Is Right” or “Don’t Lie to Me”, for example), while Radio City has more ambivalence, more opacity, a little more willingness to send a kiss-off (“Life Is White”), although, to be clear, the difference is not as pronounced as this comparison sounds.

I think the real distinction is that Radio City has more variety and complexity in the songwriting and musical style itself, while still unmistakably being the same band of #1 Record. (Third / Sister Lovers, by comparison, is of a decidedly different sound than the first two.)

This becomes apparent right away, as opener “O My Soul” is their longest track to date, 5:40 and not structured like a typical pop song, full of long instrumental runs driven by an organ. The fuzz-box guitar on “Mod Lang,” a departure from the band’s signature Stratocaster quack and use of flanger, makes the song (along with its title) the most explicit Kinks homage the band ever did.

“Life Is White” comes second on the album, another sign that this is a different album than #1 Record— the opening line “Don’t like to see your face” is harsher than anything on that album, a sign perhaps of a more mature, or just more jaded, songwriter– we’re past love, we’re past even the fights of “Don’t Lie to Me”; our singer is done with the subject of this song, and making himself move on for his own good. (“And I don’t want to see you now / ‘Cause I know what you lack / And I can’t go back to that”)

Andy Hummel takes lead vocals on “Way Out West,” I think the only time he (or anyone besides Chris Bell or Alex Chilton) does on those first two albums. He does a fine job; I feel like this probably works better with him singing than Chilton. Chilton’s a little more weary and cynical in his vocals by this point; this song is a more plainspoken entreaty, like was so common on #1 Record.

“What’s Going Ahn” is another relatively spare song, although again one showing a maturing, questioning narrator. “(I’m starting to understand / What’s going on and how it’s planned”) That spareness is largely explained by the split between Chilton and Chris Bell. Bell left the band between the first and second album, and the difference shows. (The increased angst is probably due to Chilton’s increased control of the songwriting, as you’d see how he’d go full-blown in that direction in the next album.) Bell was more of a studio technician than Chilton, and he was apparently responsible for so many of the harmonies and the gloss of the first album, which are often missing or less prominent here. He doesn’t completely disappear, though; he had a hand in writing some of the songs, and that’s clearly his voice on “Back of a Car.”

Sadly, Bell would die in a car accident in 1978. The solo album he recorded after leaving Big Star was (much like the definitive version of Third/Sister Lovers) finally released by Rykodisc in 1992; I Am the Cosmos is outstanding, and contains at least one ballad that stands with the best of any Big Star ever did1, “You and Your Sister.”

1 – Except “Thirteen.” “Thirteen” stands alone.

Of course, this album peaks with one of the finest pop songs of all time, “September Gurls.” Chilton outdoes the Byrds here with the chiming guitars and the harmonies; it’s a groovy jam that sparkles and shines. With the angsty and lovelorn lyrics backed by gorgeous music, elevated by that shimmering bridge and solo, and pulling it all off in under three minutes, “September Gurls” is everything a power-pop song should be. Perhaps more than any other song, “September Gurls” is the indelible document of Big Star2, the perfect power-pop song, whose DNA infected artists ranging as wide as The Only Ones, The Soft Boys, The Bangles, The Replacements, Teenage Fanclub, Fountains of Wayne, Wilco, Of Montreal, and many more, including… Katy Perry. (What, you thought she named a song “California Gurls” by accident?)

2 – Again, except “Thirteen,” although “Thirteen” is less “the perfect power-pop song” and more “the perfect love ballad.”

As if Chilton knew he couldn’t top “September Gurls,” the album closes with two simple, short ditties– “Morpha Too,” a somewhat cryptic tune that seems to be a love song– or at least, somewhat cryptic compared to final track “I’m in Love With a Girl,” which is about as straightforward lyrically and musically as its title implies– just Alex Chilton, with a guitar, professing that he’s in love with a girl, the finest girl in the world.

I didn’t know when I started this article how much I would have to say about the album. (I didn’t cover every track, that’s for sure.) It’s a strange place to be: I’m writing about an album that was so important to me (and so formative to my power-pop tastes), one that still ranks among my all-time favorites, but unlike some of my previous efforts in this vein, I have no unique story here, and Radio City and Big Star are an album and band that have been lauded by fans and critics for not getting their due for a long time– certainly well before I finally discovered them in 2000. (Hell, one of my other favorite bands, The Replacements, name-checked them in 1987 with “Alex Chilton,” Paul Westerberg’s open love letter to Big Star.)

I did, however, feel like I couldn’t let our YOTM 1974 go without paying tribute to them, and on the off chance some of you haven’t heard them, I want to reiterate: This a gorgeous and wonderful album, one everyone should hear at least once. You’ll hear Big Star’s influences readily throughout– some of which I’ve mentioned– but just as importantly, if you’re a music aficionado, you’ll hear their influences in so many of the bands you already know. It’s an all-timer of an album, and it’s a shame Big Star never got their due in their time, but fortunately for them and us, real art endures.