Once upon a time, you had to actually grow up with someone to reminisce about your shared childhood. But now, thanks to the mass media, people from wildly different backgrounds can connect online over the TV and movies of their youth. Spongebob shirts and Little Mermaid tattoos aren’t just socially acceptable now, they’re practically required.

But not everything has such a fond place in our collective memory. Give or take a few outstanding outliers — your Seasame Streets, your Mister Rogerses — the very first media we experienced gets treated with half-remembered indifference at best and outright loathing at worst. Hi, Barney! How’s Caillou? And if the media in question’s a flimsy attempt to disguise education as entertainment? Forget it.

In this, as in so many ways, Dr. Seuss was on another level from his peers. If anything, he got into the edutainment business because he resented the state of the genre as much as the millions of bored kids and parents who endured it. He explained the genesis of Beginner Books to the New York Times with his usual yarn-spinning wit:

Every year, just a moment before Christmas, millions of Americans named Uncle George race into a bookstore on their only trip of the year.

“I want a book . . . that my nephew Orlo can read. He’s in the first grade. Wants to be a rhinoceros hunter.”

“Sorry,” says the salesman. “We have nothing about rhinosauri that Orlo could possibly read.” “Okay,” say the millions of Uncle Georges, “give me something he can read about some other type of animal.”

And on Christmas morning, under millions of trees, millions of Orlos unwrap millions of books…all of them titled, approximately, Bunny, Bunny, Bunny.

This causes the rhinoceros hunters to snort, “Books stink!” And this, in turn, causes philosophers to get all het up and write essays entitled “Why Orlo Can’t Read.”

So…one day I got so distressed about Orlo’s plight that I put on my Don Quixote suit and went on a crusade. I announced loudly to all within earshot, “Within two short weeks, with one hand tied behind me, I will knock out a story that will thrill the pants off all Orlos!”

It wasn’t as easy as that, of course, and he goes on to tell a long and almost certainly embellished story about his struggle to write The Cat in the Hat at his readers’ level (as determined by educators “with divining rods or something”). And it’s true. You can’t make good art for small children in two short weeks with one hand tied behind you. For one thing, the whole process requires tying both hands and at least one foot. First, you have to cram in all the required educational content, which leaves precious little room for entertainment value. Then you have to remember that the reason kids need all these very basic lessons is they’re kids, and if you get too sophisticated, all you’ll do is lose them.

At least, that’s the conventional wisdom. If simplifying content enough for young children tends to end poorly, Hop on Pop, subtitled “the Simplest Seuss for Youngest Use,” sounds about as unappealing as possible. It seems wrong to call anything about the first children’s author almost anyone could name “underrated,” but it’s easy to overlook what he accomplished here. Who but a genius could write a book that’s simple enough to entertain toddlers and still funny enough to entertain adults?

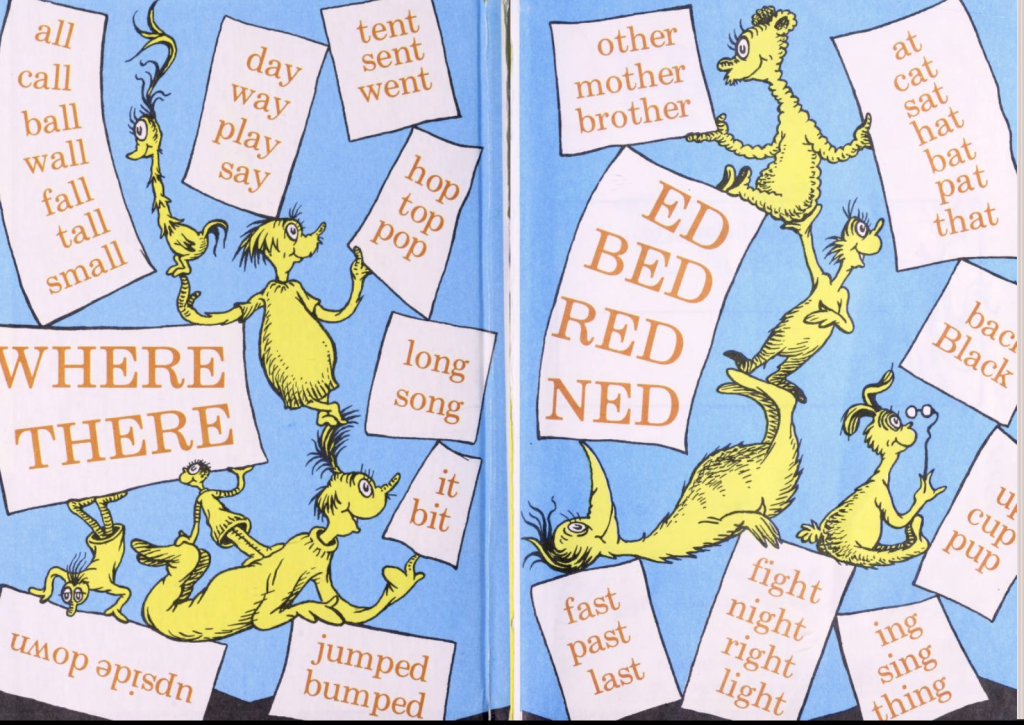

Hop on Pop showcases Seuss’s refusal to be boring the moment you open it. What could be less intriguing than a list of vocabulary words spread across the endpapers? But Seuss makes it exciting, building an acrobatic collection of distinctive personalities the way a monk would doodle in the margins. (My favorite’s the little Kilroy-looking dude at the bottom left standing on his head and holding the word “upside-down,” of course, upside-down.)

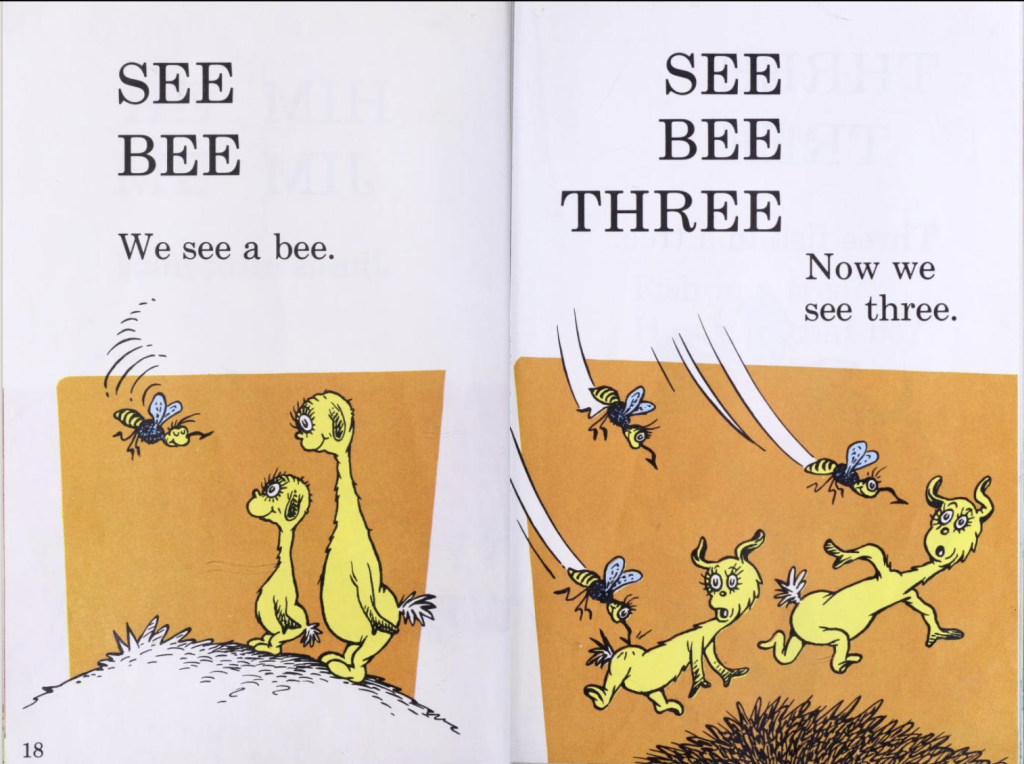

Seuss got into the literacy game in large part because of his contempt for his competitors. While the Times article goes after the (mostly) fictional Bunny, Bunny, Bunny, Seuss was blunter with the Saturday Evening Post: “None of the old dull stuff: Dick has a ball. Dick likes the ball. The ball is red, red, red.” Most of us were lucky enough to be born post-Seuss and not have to endure the Fun* with Dick and Jane series, but to his first generation of readers, he must have been a godsend. You can tell Seuss is having fun with expectations in Hop on Pop. Many of the disconnected two-page vignettes start with the kind of sickeningly cute crap you’d expect from an easy reader before descending into comic anarchy. Some are gently surreal

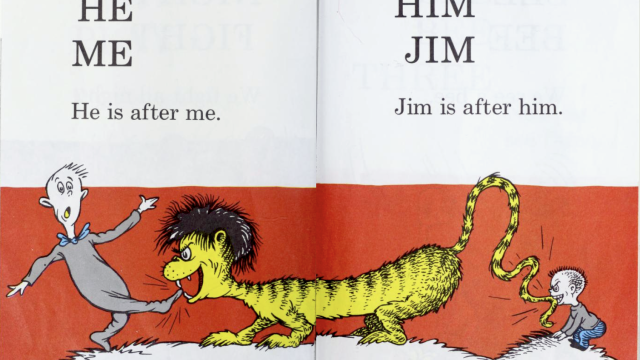

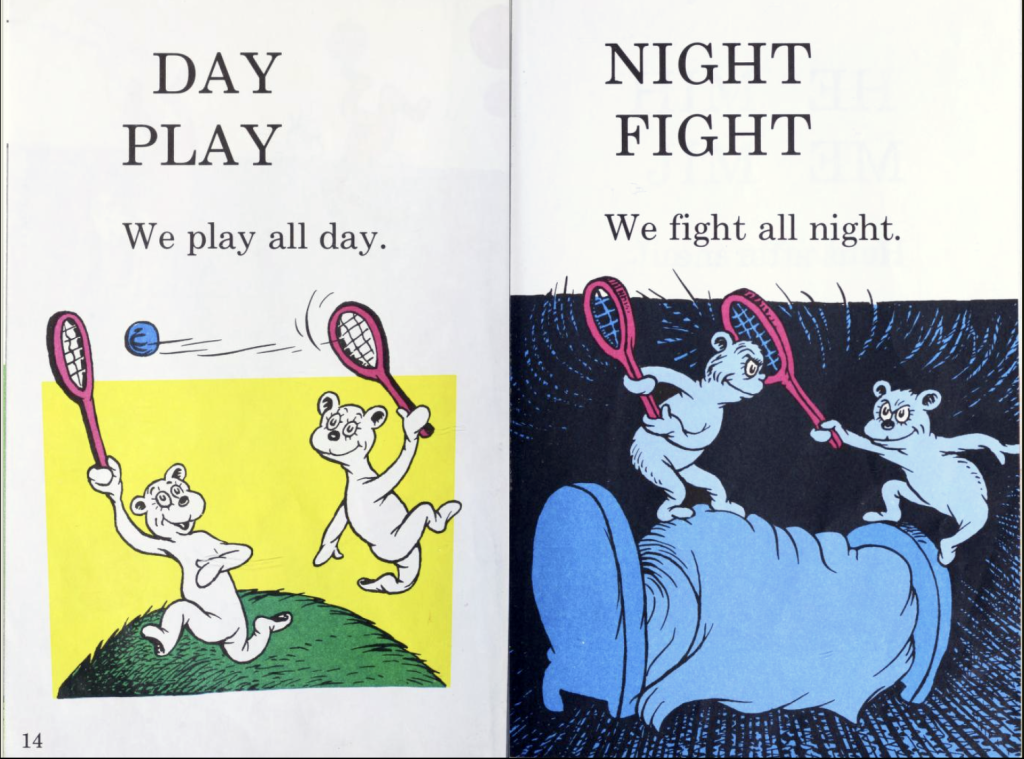

Others are more hysterically violent, like this one where two obnoxiously adorable little bear things with My Little Pony eyelashes turn out to be just as nasty as anyone else when the sun goes down.

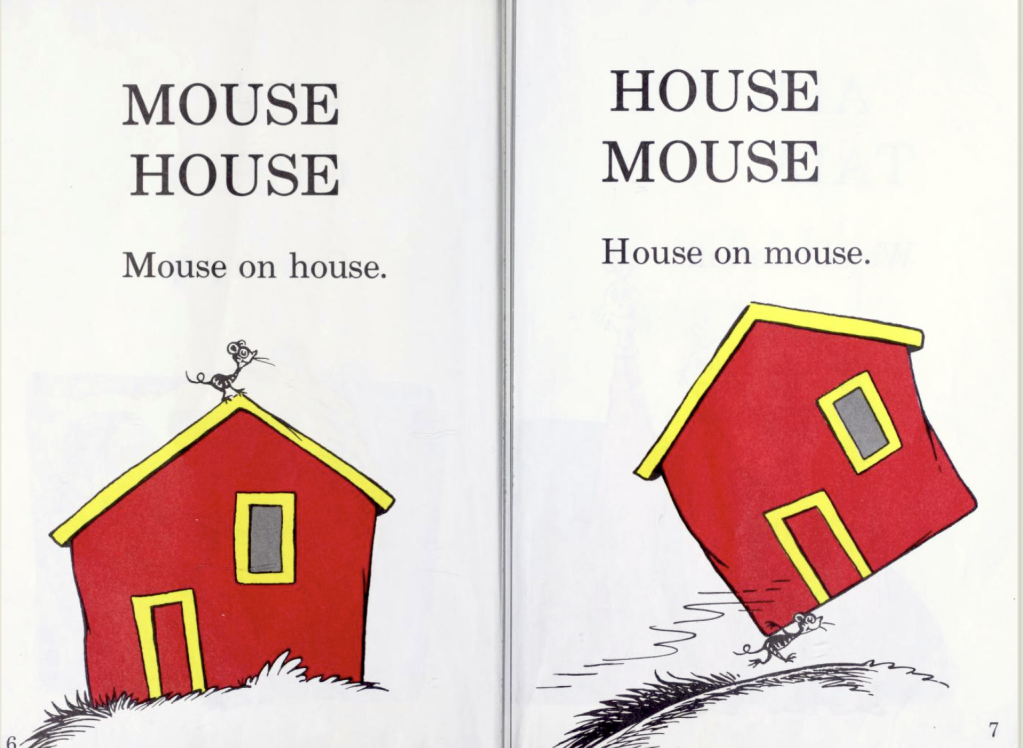

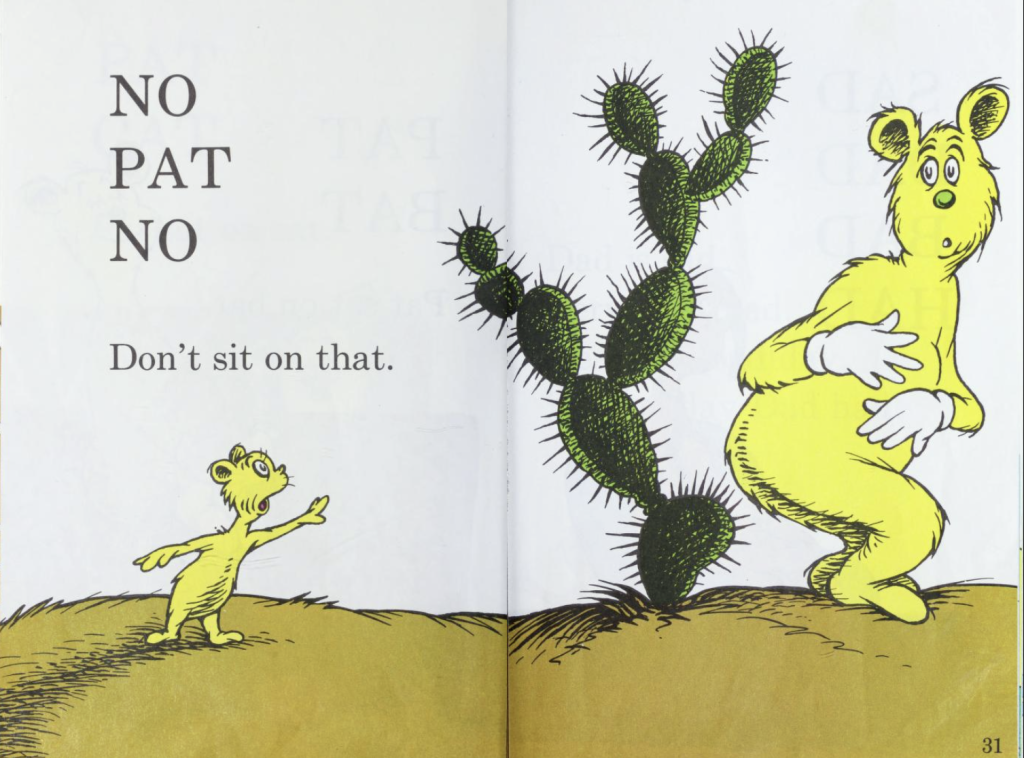

Or this one, where a pastoral scene quickly turns painful.

Or this one, where a pastoral scene quickly turns painful.

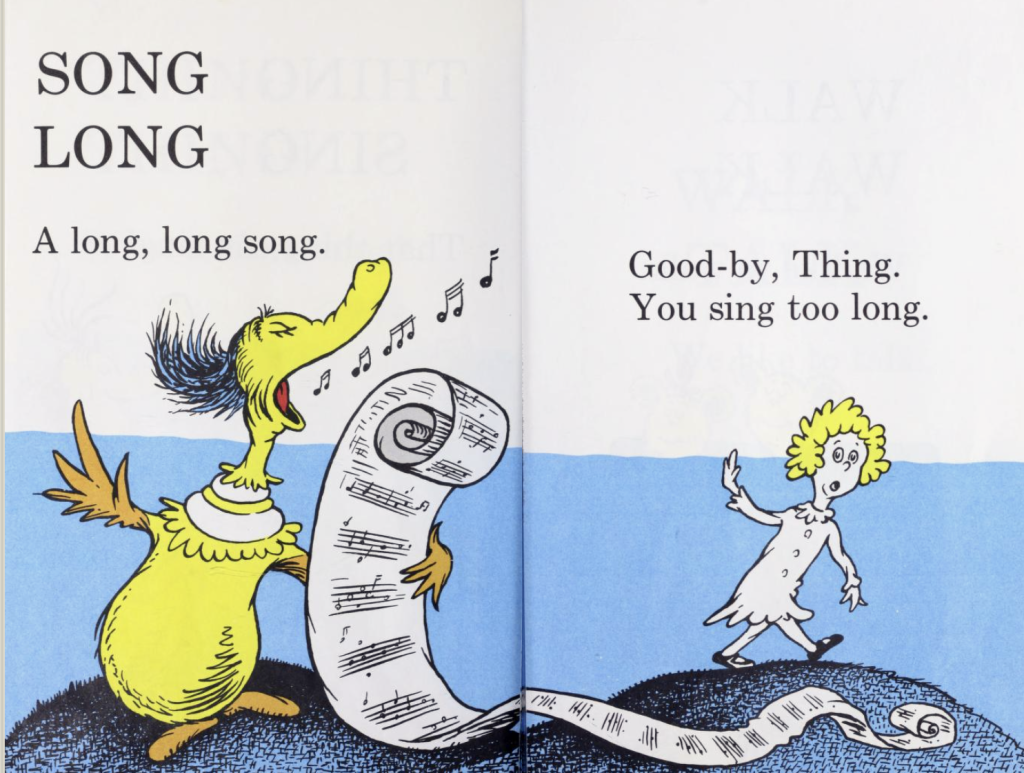

Other sections are, in an extremely relative sense, more patient. The joy of discovering a mysterious singing “thing” lasts two whole pages before the observer decides “Goodbye, thing, you sing too long,” a simple joke that becomes hilarious thanks to the thing’s operatic gestures and the transition from a little lyric pamphlet to a scroll that cascades all across the page.

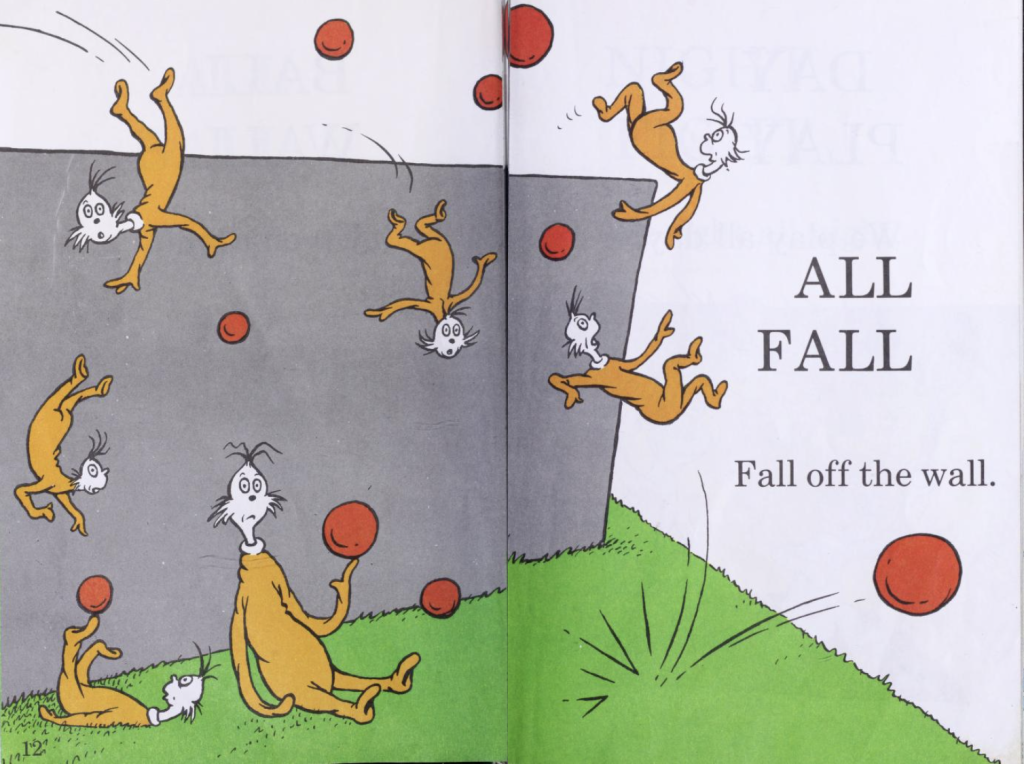

Slapstick is both the most appealing and upsetting type of comedy for little kids. It’s humor in its simplest form:

but readers who are still learning to distinguish reality and fantasy are as likely to feel the fall guy’s pain as laugh at it. Seuss threads the needle with another great bit of set-em-up and knock-em-down. “ALL/BALL/We all play ball./ALL.WALL/Up on a wall” and just when you’re noticing how precariously narrow that wall is, all the critters fall off en masse. But none of them are in pain. They’re all some variety of confused or resigned. More importantly, they’re each a different variety of confused or resigned.

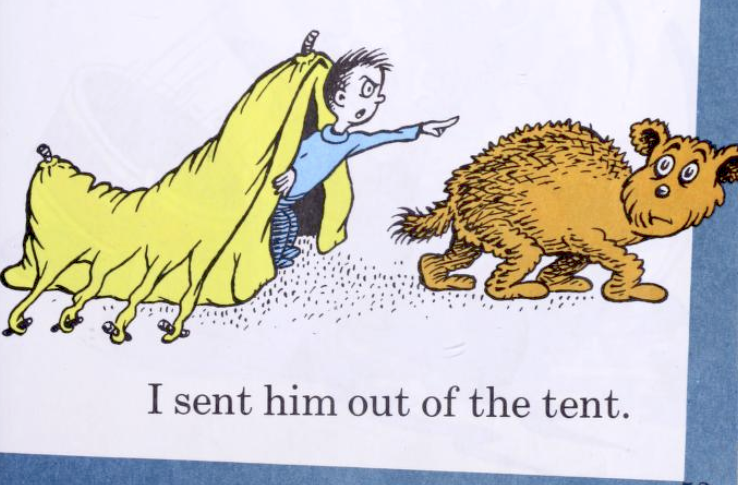

Even though few of Hop on Pop’s characters get names (or identifiable species), they’re all full of personality, which is no small thing compared to the dead-eyed doll-people populating most picture books. The expression on the bear getting sent out of the weird, octopus-staked tent should be immediately familiar to anyone who’s ever caught their dog where it’s not supposed to be.

Even though few of Hop on Pop’s characters get names (or identifiable species), they’re all full of personality, which is no small thing compared to the dead-eyed doll-people populating most picture books. The expression on the bear getting sent out of the weird, octopus-staked tent should be immediately familiar to anyone who’s ever caught their dog where it’s not supposed to be.

Escalation is another arrow in Seuss’s comedy quiver, with the introduction of Pat, whose choice of seat goes from inappropriate (a hat) to uncomfortable (a cat) to impossible (an upright bat) to, in the moment that always had li’l Sam howling, downright painful.

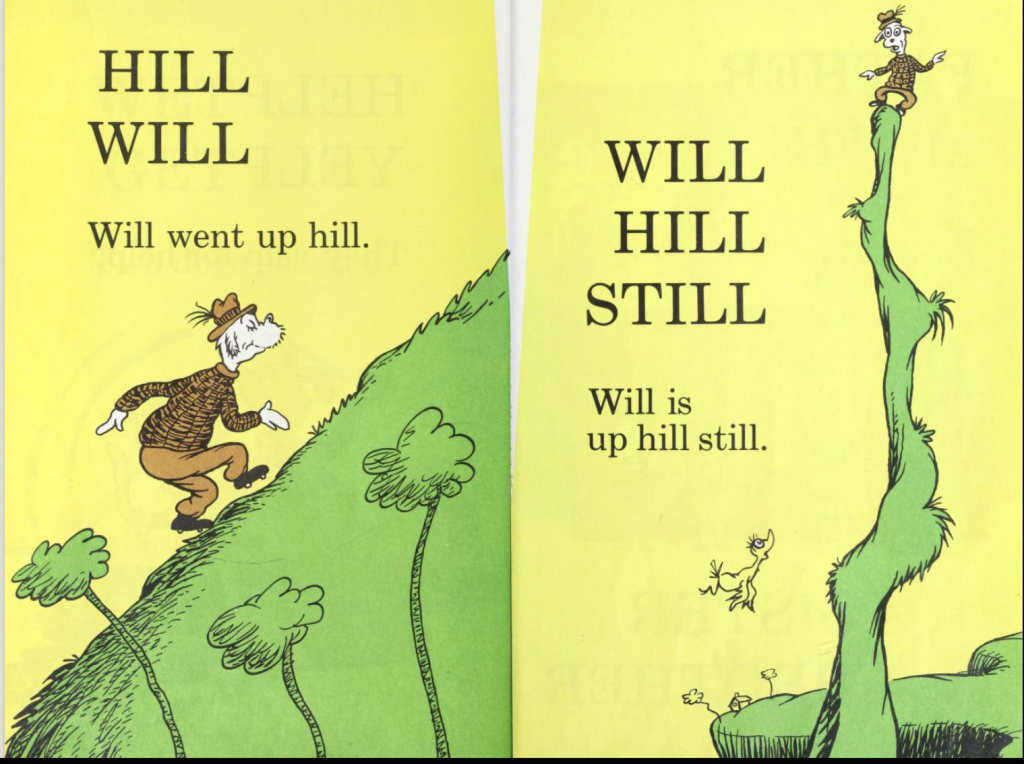

And the classic Seussian surrealism is well represented too. With some careful use of POV, the author sets up the punchline of Will walking up an apparently gentle incline before pulling back to reveal he’s on top of a wonderfully fucked up, narrow, twisting precipice.

One reason that kids grow out of books and shows like this so quickly is the endless repetition — comforting when they’re very young, mind-numbing as soon as they get older. Using it to hammer in vocabulary words sounds especially obnoxious in theory. But repetition is also one of the fundamentals of poetry, and if that’s too lofty a word for Hop on Pop, it comes darn close with passages like

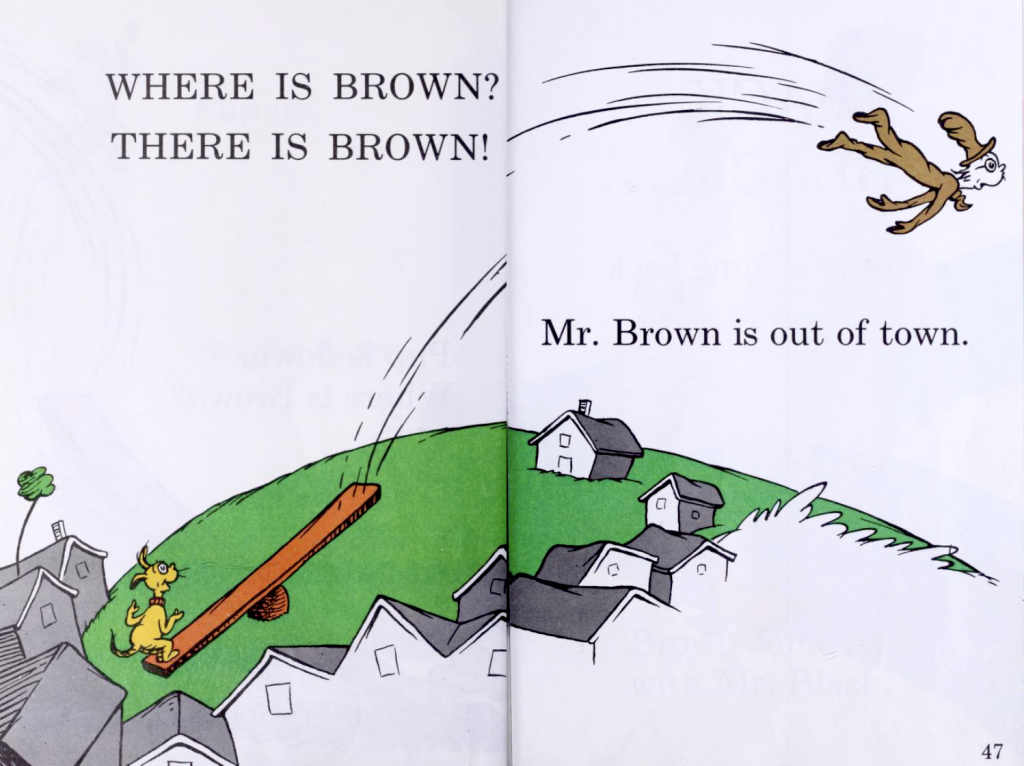

Pup is down.

Where is Brown?

WHERE IS BROWN?

THERE IS BROWN!

Mr. Brown is out of town.

And poor Mr. Brown’s ragdoll physicality and bugeyed confusion make it great comedy too.

For most of its page count, Hop on Pop shows Dr. Seuss taking one of the most effective ways to teach reluctant students — making them think they’re not learning anything at all. At the end, though, Seuss goes a step further to get kids actively excited about learning, promising that when they get older, they “can read big words too, like Constantinople and Timbuktu.”

He ends with an advertisement for the concept of learning itself. One fuzzy-headed critter looks at a mishmash of syllables and asks, “Say/Say/What does this say?” while another happily replies, “Ask me tomorrow but not today.” You can always know something tomorrow you don’t know today, and finding the joy in that, more than learning how to sound out “cat,” is one of the best lessons Seuss ever taught me.

*citation needed