So I read in my local newspaper today that one of the mental hospitals in the area is now closed to involuntary admittances, because there’s a shortage of psychiatrists. In the reading I’m doing for the book I’m writing about the intersection between mental illness and poverty, I came across the belief that the US currently has ten percent of the beds it needs to house the mentally ill who need to be institutionalized for their own safety. A friend of mine has finally, after several years, had his first therapy appointment, and they’re suggesting that the diagnosis he’s had for years might be wrong. Which is possible, but it’s also possible that he has fallen victim to New Psychiatrist Syndrome; another friend feels the need to present all new mental health professionals with a list of every diagnosis she’s ever had, so they can pick the one they believe and shorten the process.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, 18.6% of all US adults could be considered mentally ill in 2012. That’s about 43.7 million people. Not counting the homeless, a population known to have a serious mental illness problem, or—perhaps ironically—the institutionalized of whatever variety. So you’ve got to figure that number is low by quite a lot. We’ve got to be looking at somewhere around twenty percent, possibly more.

Now, I ask you. Do you think one in five of the characters you saw in American movies last year were diagnosably mentally ill, leaving out addiction?

To be fair, mental illness is what is called an invisible disability. Mental health issues severe enough to be categorized as mental illness can be two weeks where you can’t ever seem to quite cheer up, even though your symptoms are mild enough so that the people around you don’t necessarily notice it. Severe mental illness? That’s probably closer to five percent of the population. That’s people like me, who during the worst of our episodes basically can’t even move. Or John Nash in the movie version of A Beautiful Mind, where he has a hallucinatory roommate. The kind of mental illness people think of when they think of mental illness, in other words.

But even there, we are still underrepresented. I’m not going to crunch numbers, here, but aside from the odd megalomaniac in a superhero movie, I’m not sure I saw much at all in the way of mental illness in the movies I saw in the theatre last year. We might as well not exist unless we’re needed for plot reasons. No one in movies ever just happens to be mentally ill, and most often, when we’re needed, we’re needed to be a villain. At least on TV, we’re also allowed to solve crimes as well as just commit them.

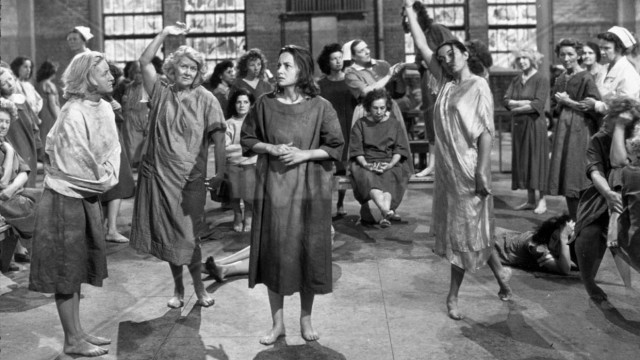

The history of mental illness as an Issue Film goes back to at least Olivia de Havilland in The Snake Pit (a movie I caught half of on AMC or the CBC or somewhere once and am kind of dreading watching all the way through). You can be nominated for an Oscar for playing one of us, because it’s your standard Oscar bait handicapped role. Though Olivia de Havilland lost to Jane Wyman’s developmental disability character in Johnny Belinda, and Russell Crowe lost to Denzel Washington in Training Day. So I don’t know; can you win playing one of us? I guess Angelina Jolie did. I haven’t seen Silver Linings Playbook yet; is Jennifer Lawrence’s character mentally ill?

A lot of those issue movies are about women, too, I suddenly notice. When it’s a man, getting laid by the right woman can replace his meds, from what I can tell. I have a friend who is so extraordinarily angry about the handling of mental illness in Matchstick Men that I’ve never seen it. You see, I get angrier at movies than she does, and if she’s that mad, how mad would I be? But the answer is almost always “Oh, you don’t really needs your meds,” and if any message in Hollywood is actually killing people, it’s that one.

A lot of the people I know (I know a lot of mentally ill people) have a habit of trying to diagnose characters in movies when there are explicitly mentally ill characters in movies. This isn’t “does Sherlock Holmes have Asperger’s?” This is “is Joon from Benny and Joon schizophrenic, do you think, or is it something else?” More often than not, the character has what I think of as “Hollywood Crazy Person Syndrome,” where they have a handful of symptoms that are almost never correlated in the real world. Like most of the characters in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, for example. Sometimes, that’s even the case when the character gets an onscreen diagnosis; I promise you that the symptoms the actual John Nash had didn’t look like Paul Bettany.

This is probably fairly disjointed, because I’m experiencing a depressive episode as I write, and that makes for bad writing when I can manage anything at all. But is it any wonder we have a hard time telling people about our conditions? The absolute best we can hope for in pop culture is your standard Magical Crazy Person, of which Manic Pixie Dream Girl is arguably a subset. There has to be something better.