Picking up from where I left off last year, during the Halloween season, I write about films that don’t so much bludgeon your skull, as mess with your head. Previously in this series, I covered Marathon Man, Safe, Seconds, and A Scanner Darkly. In all these films that borrow from the horror genre, the blood and gore is kept to a relative minimum, while showing us, in unforgettable ways, how we are haunted by our own demons that manifest social obsessions with security, success, and surveillance.

Horror films often resemble bad dreams. Some dreams, however, don’t seem to end. These kinds of dreams, often shaped by traumatic experiences, deconstruct our sense of real time—disrupting the linear progression of past, present, and future. When this occurs, all sorts of psychic connections emerge, as we will now see.

In 1977, an English punk band, the Sex Pistols, hot-wired a prototypical 50s guitar riff and transformed it into “God Save the Queen,” a raging mockery of a nation in decline that had turned to nostalgia to escape its problems. Johnny Rotten, the Pistols’ (in)famous lead singer, spat out the question: “When there’s no future, how can there be sin?” Exposing the corrupt morality that propped up the ruling class, the historical appropriation of the swastika by the punk movement was intended to compare England with Nazi Germany—a fascist regime that had no future.

A year before, Werner Herzog forecast such an apocalyptic mood. He co-wrote and directed Heart of Glass (1976), a strange and twisted look (having no relation to the Blondie song with the same title) at the agrarian past of Germany, the same memory-image that frequently turned up in Nazi propaganda. To impart a sense of psychological realism to this dissolute mythic landscape, Herzog, it was rumored, had the majority of the cast put under hypnosis while filming. While it is debatable that the actors could even perform in such a state, it feels, at times, as if they were directed by Herzog to ignore social rules for displaying emotions. What we see is a barely suppressed desire expressed by all involved in this project to wreck any idea of a conventionally filmed scene.

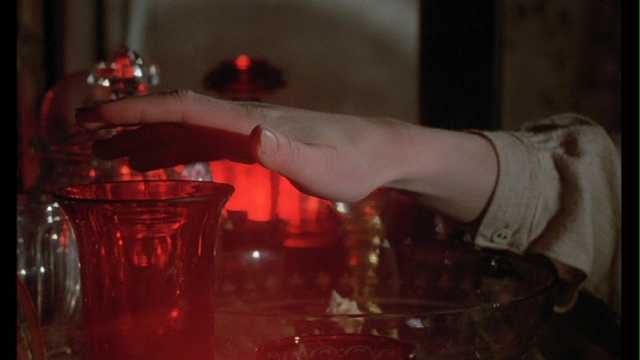

The premise of Heart of Glass unfolds as a grim lesson in historical determinism: after an elder artisan dies, the loss of the knowledge of how to make the ruby glass on which the townspeople economically depend creates a village of the damned. Already socially isolated, these people have slipped out of the time stream that flows forward, to modernity, and are plunged backwards into madness, delirium, and an archetypal fear of monsters that symbolizes the past unknown.

In a cinematographic parallel, the use of natural light creates a dark, shadowy world, contrasted only by the fiery interior of the glassworks. Here salvation seems far away—as it also does in the natural landscape, where a breathtakingly complex shot of clouds cascading over the forest tree line like a massive waterfall only intensifies the feeling of a distanced humanity.

Herzog’s pushing the boundaries in several ways here. The music by Popul Vuh, a German art-rock band that scored several of Herzog’s films, is far from what you’d expect in a horror film. At first, the score feeds off of the hypnotic pull of the visuals: layers of guitars, sitars, and flutes moving slowly like clouds over the landscape. Yet because it was influenced by East Indian classical music, the score eludes a Westernized sense of resolution, thus pushing us further off balance.

The sense of terror comes both from the town’s psychosis, which we, of course, can’t quite grasp completely, and prophecies about the future made by Hias, a shepherd: a few or maybe more which we can understand–these prophecies, for us, having already become history–but the townspeople can’t. And this leads to Hias being viewed with suspicion, for his having the uncanny power to look into the future. As in the case of Stalker, we feel uneasy about the fates of those who are judged to have superhuman attributes.

Hias predicts a fire will occur at night. The unnamed heir to the glass business, having an aristocratic attitude of being above the law, murders a young woman servant and then burns down the glassworks. In a bleakly comical example of attempting to kill the messenger, the distraught townspeople think that Hias bears at least some responsibility for the fire and physically threaten to lynch him. The next scene shows him and the heir sharing a prison cell, both regarded as outsiders.

Hias predicts a fire will occur at night. The unnamed heir to the glass business, having an aristocratic attitude of being above the law, murders a young woman servant and then burns down the glassworks. In a bleakly comical example of attempting to kill the messenger, the distraught townspeople think that Hias bears at least some responsibility for the fire and physically threaten to lynch him. The next scene shows him and the heir sharing a prison cell, both regarded as outsiders.

Most of what Hias says is cryptic. One prophecy, however, expresses a far greater and more horrifying vision of psychosis—not just a rural German town, but the entire nation driven over the edge: “Then the little one starts a war and the big one across the ocean extinguishes it. . . . Then a strict master comes who takes people’s shirts and their skins with them.” This alludes to Hitler’s rise to power, resulting in murder technologically expanded on a genocidal scale, the incineration of cities with advanced weapons.

At the end of the film, Hias, in what perhaps is a snowbound exile from the town, encounters an imaginary bear. He kills and eats it. The trauma of the night of the fire, his subsequent punishment, the burden of seeing the future—some or all of which have deranged his senses.

In an irony that couldn’t have surfaced until recently, this scene foretells a film that Herzog would make nearly 30 years later. Grizzly Man (2005) documents a self-appointed protector of bears whose friendship with these animals becomes fantasy, in the most tragic sense, when he and his girlfriend are killed and eaten by one. In Herzog’s eminently quotable and controversial voiceover, he argues that we must accept that bears are driven purely by their survival instincts; they are different from us in a fundamental way that we can’t possibly try to understand.

Hias tells us a final story. A group of islanders, grappling with the fear that the world is flat, sends out a small number of men on a boat to investigate. The conclusion of the story and film (translated from German): “It may have seemed like a sign of hope . . . that the birds followed them out into the vastness of the sea.”

Heart of Glass warns us that, whatever knowledge could save us from the destructive forces of nature or technology, it comes too little, too late. This is the nightmare that horror films tend to dramatize—what is more terrifying, after all, than the moment when you want to hope that, at last, the threat, the fear is over, but it isn’t?

And, when a horror film is over, the sense of anxiety goes away, but slowly. There are stories that after people watched Jaws, they were afraid to swim in the ocean. Few of us have the concern that we’ll fall off the edge of the world, yet the psychological fear of falling remains.

Heart of Glass insists, however, that we can never leave the historical theatre. Thus Herzog reminds us that we need to take the fears we project on the screen seriously. There’s always another reel left for us to watch.