Directed by Richard Linklater, The Waking Life (2001) uses rotoscoping—the film first shot on digital video then each frame drawn over by computer-aided artists—to explore different philosophies about existence. The colors and shapes dance together, each movement opening a perspective on a philosophical universe, suggesting connections among ways of living. The Waking Life seems almost defiantly optimistic, as it challenges us to join in the dance.

Revisiting this technique five years later, the film I will now discuss goes in the precisely opposite direction: reminding us that paranoia is a more negative reaction to the idea that everything is connected. Inspired by Philip K. Dick’s novelistic channeling of his own drug-damaged life, what we will see onscreen is a powerfully terrifying desire for redemption.

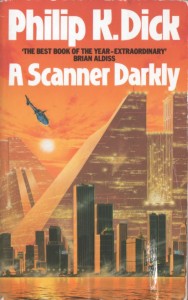

“Slow Death”: A Scanner Darkly

(dir Linklater 2006)

In the film, there seems to be something missing, as if crucial footage were mistakenly left on the cutting-room floor. Challenging the narrative logic of horror films that tend to rely heavily on plot, A Scanner Darkly unfolds as a series of rotoscoped hallucinations, some perhaps shared. The question of what is real becomes a punch line for a cosmic joke.

The opening scene throws the first curveball at us: an undercover narcotics agent gives a speech at the Brown Bear Lodge. Introduced as Agent Fred, he stands out from the suit-and-tie-wearing crowd by wearing a “scramble suit” that conceals his appearance behind split-second flashing images of multiple faces and outfits. Underneath the disguise is Bob Arctor, who argues with his boss, via remote feed, about the text of the speech: he is to act as a cheerleader for the latest war on drugs, this time against Substance D, the most addictive drug yet seen. Deviating from the prepared text, he ends the speech in front of a now stunned audience:

Substance D. ‘D’ is dumbness, and despair, desertion—desertion of you from your friends, your friends from you, everyone from everyone. Isolation and loneliness… and hating and suspecting each other, ‘D’ is finally death. Slow death from the head down. Well… that’s it.

Arctor is played by Keanu Reeves, who demonstrates why he should be the first on the call list for any role that features a dim realization of being in over one’s head.

His assignment, already in progress, is to spy on the users who are living at his house. They are James Barris, a sarcastic pharmacological expert who moonlights as an informant, and Ernie Luckman, a hyperactive surfer dude. Also in Arctor’s immediate orbit is Donna Hawthorne, a dealer and his girlfriend.

While Hawthorne, played by Winona Ryder, illustrates that living in one’s head is not an exclusively male trait, nearly stealing the show is Robert Downey Jr. as Barris, who rips into his putdown lines, such as this one directed at Luckman, played by Woody Harrelson:

Alright, I’m gonna give you a little feedback since you seem to be proceeding through life like a cat without whiskers perpetually caught behind the refrigerator. Your life and watching you live it is like a gag-reel of ineffective bodily functions.

The scenes featuring Arctor, Barris, and Luckman are not just some sort of twisted comic relief but the emotional center of the film: we feel how hard it is to make personal connections when not only do we not know who the people we are trying to connect with are, but we are not sure of who we really are. And not knowing which side of the law they—or we—are on.

Their arguments memorably illustrate what happens when paranoia gets out of control, turning our frame of reference upside-down and inside-out as each person has an equally bizarre and obsessive way of looking at things. But the comedy flips into horror as we start to get a sense of the moral emptiness these arguments try to hide. The lives of these people all revolve around—and are thus connected by–drugs. It is the stark and rather unfunny logic of addiction. Our laughter at these episodes makes us feel somewhat uneasy, almost as if the film is mocking us for our inability to take addiction seriously. If we did, we would have to ask: why are these characters, in fact, so paranoid?

The answer the film gives: why are you, the viewer, not? Because the surveillance in the film has long been a feature of our own daily lives, whether we choose to acknowledge or react to it. As the film would remind us, it can seem a rather small step from “just say no” to being judged as guilty before being proven innocent.

When Arctor is asked to look at the scans of his own house, his alarm at this ethical conflict is met by his boss telling him to edit out most of the shots of himself, leaving just a few images for reference purposes. His spying on himself, internalizing the police state apparatus, parallels the effects of Substance D, which he has been taking as part of his undercover work, that has caused him to not know whether he is Agent Fred or Bob Arctor.

Doctors explain to him that there is crosstalk between the left and right hemispheres of his brain. Is this the internalized chatter of the surveillance scans? Thought of in this way, language is ultimately disruptive, a theme that, in a horrifying way, A Scanner Darkly takes far beyond that of Hollywood films. For, typically, a film uses language to tell us what characters are feeling and thinking. Now, recall the earlier scenes in A Scanner Darkly. We have no idea what these characters are feeling, because they are in various states/stages of denial; we have no idea what these characters are thinking, because they are succumbing, to various degrees, to psychosis. Language therefore does not bring anyone together in this film; nor is the impression even given that language holds self-identity together.

The ending of the film brings this horror into sharp relief. Arctor/Fred has fallen apart to the point at which he becomes an ideal patient for The New Path, a popular drug recovery program, that his superiors want him to infiltrate to trace its possible ties to the manufacturing of Substance D. In the last scene, he is taken to a field by a program assistant and sees the blue flowers that are harvested to make the drug. Then the following text in white appears against a blank screen:

The ending of the film brings this horror into sharp relief. Arctor/Fred has fallen apart to the point at which he becomes an ideal patient for The New Path, a popular drug recovery program, that his superiors want him to infiltrate to trace its possible ties to the manufacturing of Substance D. In the last scene, he is taken to a field by a program assistant and sees the blue flowers that are harvested to make the drug. Then the following text in white appears against a blank screen:

This has been a story about people who were punished entirely too much for what they did. I loved them all. Here is a list, to whom I dedicate my love: To Gaylene, deceased To Ray, deceased To Francy, permanent psychosis To Kathy, permanent brain damage To Jim, deceased To Val, massive permanent brain damage To Nancy, permanent psychosis To Joanne, permanent brain damage To Maren, deceased To Nick, deceased To Terry, deceased To Dennis, deceased To Phil, permanent pancreatic damage To Sue, permanent vascular damage To Jerri, permanent psychosis and vascular damage …and so forth In memoriam. These were comrades whom I had; There are no better. They remain in my mind, and the enemy will never be forgiven. The ‘enemy’ was their mistake in playing. Let them play again, in some other way, and let them be happy. Philip K. Dick

This is the end of language, of meaning, a virtual gravestone.