Bob Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man” (1965) memorably wrote off the established Company Man, stuck on the losing side of the generational war. As the song depicts, no matter what Mr. Jones does to be hip and with it, such as reading all of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books, he remains out of touch. Dylan’s sneering delivery of the refrain, “Because something is happening here, but you don’t know what is, do you, Mr. Jones?”, drives the point home in a particularly cruel way, denouncing the shallowness and obsolescence of mainstream values.

Released a year after Dylan’s song, the film I will now discuss imagines an even more horrific fate for Mr. Jones: what if he could purchase a younger self-identity? The resulting scenario registers nothing but contempt for the older generation’s fantasizing about how the younger generation lives—at the same time, however, we cannot help but sympathize for those who find out, too late, that they have been profoundly betrayed by pursuing the life they were conditioned to desire.

“Because Something Is Happening Here, But You Don’t Know What It Is”: Seconds

(dir. Frankenheimer 1966)

The disorienting credits sequence, designed by Saul Bass, sets the stage for what is to come. Images of a face are warped by the distortion of the camera lens. Dissonant music with pulsing high notes accompanies what looks like some sort of bizarre science-fiction experiment. The mood shifts as funereal organ chords wash over the image of an open mouth, suggesting an end, rather than a beginning. And that, of course, is the temporality of horror, a downward spiral that culminates in an encounter with the void or an unholy return from the dead.

Arthur Hamilton, a middle-aged man, answers a late-night telephone call in the den of his house, a symbolic site of privilege and power. A male voice on the other end claims that he knows him and delivers the hard-sell: it is his last chance to change his life. As we have watched him, he is indeed stuck in a rut. He and his wife no longer have an intimate connection; his daughter is grown up and married, living on the West Coast, a geographic mapping of the generation gap. All Hamilton has left is his high-ranking position in a New York bank, routine work which pays for his spacious house in Scarsdale and his comfortable existence.

When he decides to follow the caller’s instructions (he will go to a mysterious address and answer to the name of Mr. Wilson), the horror begins. He has no idea of what he is really getting into. After a circuitous journey through the city, he enters a waiting room. He falls asleep and has a nightmare: the perspective seems to fall away as the camera zooms and pulls back in a disjointed rhythm. The scene is silent, intensified by the blare of an organ. He is in a strange  room and moves toward a younger woman on a bed. She sees him and screams in fear. The last shot is him lying on top of her. Back in the waiting room, he wakes up.

room and moves toward a younger woman on a bed. She sees him and screams in fear. The last shot is him lying on top of her. Back in the waiting room, he wakes up.

It was not a dream, however. He has been drugged and filmed in a staged sexual assault. Under threat of this blackmail, he can no longer go back to his former life. This is a parody of the life-changing drug experience many, including and, in particular, those of his generation, had in the 1960s—especially during the brief time LSD was legal. Arthur Hamilton will vanish in a faked death (a hotel room fire); through extensive and costly surgery, he will be reborn as Tony Wilson—again a satiric take on the countercultural ethos—as a younger and more attractive man.

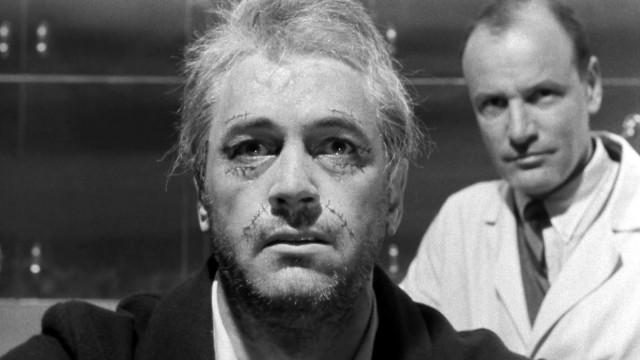

As he recovers from surgery, the actor changes to Rock Hudson. The question of who Wilson will be has already been settled. During a drug-therapy session, he unconsciously expressed a desire to be a painter. As the tennis trophy earlier seen in the den suggests, he might be better suited to be a tennis pro—the answer he first gave when asked what he would like to be—but the identity of a painter, the company believes, would be easier to fabricate.

What Seconds shows in a particularly terrifying way is how much of a myth the success of the self-made man is. As frequent shots of Hamilton/Wilson on a hidden dolly demonstrate, he appears as if he is being moved against his will; neither his former success nor his current predicament were brought about by his conscious choice. Just as he did what he was told to do in his former life (go to an Ivy-League school, network, and become a banker), he will now be forced to do what the company tells him.

At first, his new life seems promising, even enviable. He has a swank beach house in Malibu (where the beautiful people, as the media always tells us, live), a valet to attend to his every need, and paintings to imitate to develop his artistic style. But there are few times when Hudson, playing Wilson, does not look uncomfortable, as if he is ready to jump out of his skin. Because, while the company can give a middle-aged businessman a new appearance, it cannot change the lived experiences that defines who a person is.

He meets an attractive woman on the beach who takes him to a bacchanal. Drenched in wine, he still  looks confused, but a brief look of happiness eventually flashes across his face as if he is having an epiphany. At his own party, a meet and greet with his new neighbors, he again drowns in drink, but looks less attractive as he gets more and more wrecked. He starts babbling about his former life and talks to some of his guests, acting like he already knows them. Because he does; they take him aside and vent their anger at him for threatening to blow their cover. They tell him the woman he has met works for the company.

looks confused, but a brief look of happiness eventually flashes across his face as if he is having an epiphany. At his own party, a meet and greet with his new neighbors, he again drowns in drink, but looks less attractive as he gets more and more wrecked. He starts babbling about his former life and talks to some of his guests, acting like he already knows them. Because he does; they take him aside and vent their anger at him for threatening to blow their cover. They tell him the woman he has met works for the company.

Seconds suggests that Hamilton/Wilson is simply too paranoid to buy into this elaborate fantasy. If the horror resides on the surface, expressed by the almost unbelievable anguish that Hudson projects as he awakens into what has become a nightmare, a more philosophical fear emerges when he runs away and goes back to his Scarsdale home. He meets with his former wife, who, in a scene powerful for its brevity, lays bare what he once was. She knew he was unhappy, his coldness keeping her and the rest of the world at a distance. She says, “Arthur had been dead a long, long time…before they found him in that hotel room.”

That his life was never his in the first place blocks any possibilities of change. This is the critical pronouncement the film conveys: to be young is a fantasy to start over again, but what the sellers of this fantasy hide is that there are destructive socio-psychological patterns that are not easy to break. The men of the younger generation, the film implies, will be betrayed by their elders by being sent off to die in Vietnam (the first combat troops already having arrived a year earlier). Likewise, Hamilton has been betrayed by his college friend, the person who called him and talked him into being reborn. Hamilton was already dead: his new life came too late. Thus he ultimately does not escape death, becoming, when he asks for a second chance, a cadaver for the faked death of another client.